Gloomy in the wake of Charlie Hebdo, I have decided to explore the impulse to caricature, and look at some selected incidents of outrage and retaliation against cartoonists. I also am launching a personal attempt to come to terms with racist cartoons from America's past.

Gloomy in the wake of Charlie Hebdo, I have decided to explore the impulse to caricature, and look at some selected incidents of outrage and retaliation against cartoonists. I also am launching a personal attempt to come to terms with racist cartoons from America's past.

Lately, I have been thinking at lot of the indecorous and gleeful smile of my long-departed college English teacher and friend, the unpublished satirical cartoonist Bill McAndrew. I guess many of us have our individual memories and experiences which we use to make sense of the large-scale, overwhelming and distressing events of the world, such as the recent Charlie Hebdo related attacks in Paris. For me, this time, it’s Bill McAndrew.

I got to know Bill in my first year at Florida State University. Although he wasn’t much older than I, he taught my required English Composition class in 1980. Bill liked my writing and encouraged me. But we didn’t really connect as friends until we both discovered a shared love of comics and satire. The first time I ever heard about RAW was from Bill, who told me about Art Spiegelman's new magazine printed on different sizes and kinds of paper, and with some really great new and old cartoons in it. He was particularly taken with this one comic that depicted Jews and Nazis as mice and cats – at the time, a slightly blasphemous satirical reversal that we both savored.

I lent Bill my coveted VHS tape of the 1933 W.C. Fields vehicle International House, and later it was reported to me by our mutual friend, the writer-cartoonist-historian Frank M. Young that Bill was obsessed with watching the Baby Rose Marie number over and over. During the summer breaks, Bill would go back to his parents’ home, in Miami. One summer, he sent me a care package, with an encouraging letter and, from his own boyhood collection, a copy of the original 1950s Classics Illustrated comic book adaptation of Jack London’s The Sea Wolf, which I still have.

One day, early in our friendship, Bill McAndrew took me to his office, located deep in a warren of narrow hallways and irregularly-shaped cubbies in the upper floors of the musty old gothic revival building that housed the university’s English department. He pulled from his desk drawer a notebook of his own cartoons and, as he handed them to me, an 88-key grin spread across his face: full teeth, eyes crinkled and gleaming – a slightly mad look that seemed to indicate to me the sudden intensity of his glee. The cartoons, drawn on typing paper, were caricatures of his stuffy, ridiculous colleagues in the English Department, some of whom taught classes I had attended. I remember Bill nailed my boring, egoistic Shakespeare professor who was fond of reading aloud to the class his published essays. Bill drew him as a sadly unfunny court jester. For Bill, there was a conspiratorial joy in showing me these caricatures. It was a risky thing for him. If the cartoons had gotten out, they would have created problems for him, perhaps even gotten him fired.

Later, Bill showed me thick sheaves of comics he had created in high school – long stories that were filled with caricature and satire of his teachers and students. They were drawn on lined notebook paper with pencil, and although they weren’t drawn particularly well, the spirit and wit of them was sterling, and something I cherish to this day. Bill told me the cartoons were very popular among his close chums, and that they had almost gotten him expelled. He told me this proudly, a badge of honor.

Sometimes, when I see a cartoon made to prick authority, lance hypocrisy, or to just plain poke at someone – I think of Bill McAndrew, and that impish, Katzenjammer Kids, toothy grin of his. Bill McAndrew’s pride in nearly getting expelled from high school because of his cartoons was his own way of saying a few things, like “fuck you,” and “cartoons matter.” Or, as Art Spiegelmen put it on Democracy Now the day after four Charlie Hebdo cartoonists and several others were murdered, “cartoonists lives matter.”

I didn’t know the Charlie cartoonists personally. I was barely familiar with their work – but, when I saw their screwball caricatures and wacky cartoons that, as far as I can tell, spare no one, I immediately recognized in them the very same impulse that had driven my sensitive and intelligent English teacher friend to satirize the people in his own world with cartoons. It seems to me that this sort of thing is a basic part of our humanity. It’s not kind, pleasant or comfortable, but that may be the point.

The impulse to satirize with cartoons may well be a part of our birthright as humans, and an essential way that we work out our differences – in a grand, glorious, unfair, unbalanced, unhinged mess. There’s something about a cartoon image that cuts to the quick, bypassing filters and nuances, and injecting an electric jolt into the mind. Given the visceral and immediate nature of this form of communication, it’s not surprising that a strong reaction will sometimes occur: a guffaw, a spark of righteous anger, or a violent outrage, one that is sometimes planned for years and coldly executed, in all senses of the word.

In 1988, a defiant and sharply satirical Palestinian cartoonist named Naji al-Ali was shot in the face and killed by an unknown assailant. In 2005, Kurt Westergaard, another teacher-cartoonist, made a now infamous cartoon of a Muslim with a bomb in his turban and has been on the run ever since. It was part of a group of 12 cartoons published in a Danish newspaper. The cartoons, and in particular Westergaard’s prompted a huge reaction from some hardline Muslims, who saw the cartoon as blasphemy and declared their intention to murder Westergaard in revenge. In 2010, men broke into the 75-year old man’s home. Westergaard hid in his reinforced bathroom. The attackers attempted to break into the bathroom with axes, failed, and left. During this time, Westergaard’s granddaughter was in the house, unprotected and, thankfully, unharmed – but nonetheless, a shocked witness to men attempting to slay her grandfather for drawing cartoons.

In 2012, The Onion made fun of the situation in a "story" about a cartoon showing Jesus, Buddha, Ganesh, and Moses having a casual four-way. The headline read: “No One Murdered Because of This Image.”

I am the first to admit my understanding of politics is poor. I couldn’t begin to offer any incisive political commentary on anything, including the Charlie attacks. But as a historian, I can tell you this with confidence: outraged retaliation towards satirical cartoonists is not a new thing; it’s been going on for centuries.

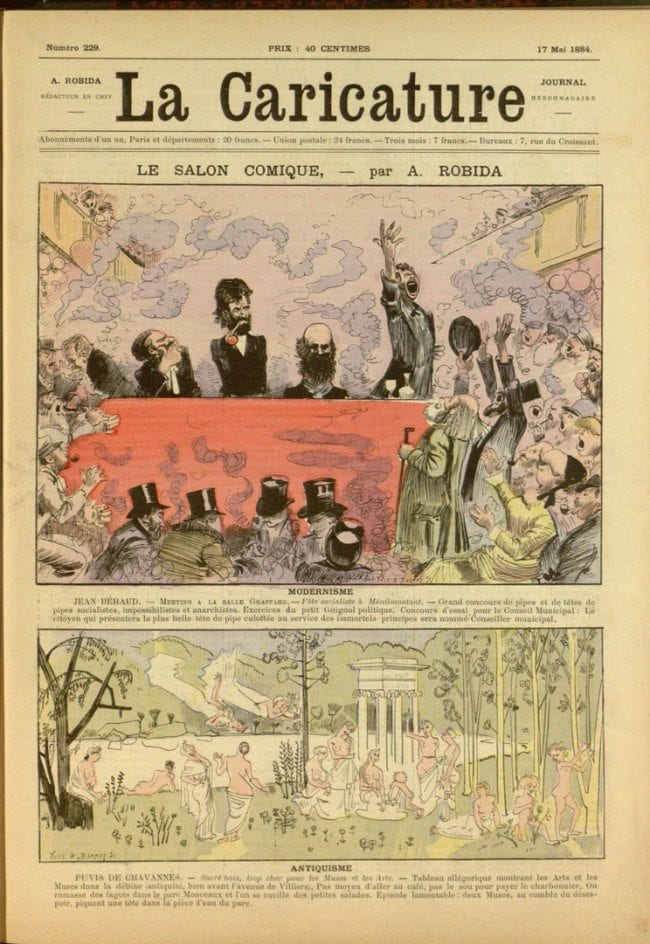

In France, cartoon-inspired outrage traces back at least to 1830 (probably long before), when censorship laws in France became more enlightened and a new magazine was founded that really rocked the boat: La Caricature. With a mission somewhat like that of Charlie Hebdo, La Caricature drilled into the existing power structures of its time and struck nerves. The famed French caricaturist Honoré Daumier joined the staff of La Caricature, along with Grandville and several other greats.

In 1832, Daumier made “Gargantua,” a remarkable cartoon which portrays the King Louis-Phillippe on his throne as a bloated glutton consuming bags of money extracted from starving peasants. While much of the working population toiled on through desperate poverty, the king paid himself a massive salary that amounts to 150 times the current salary paid the American president of the time, according to one source. In effect, the cartoon was attacking a social system where 99% of its members grow poorer with the wealthiest 1% grew richer, which, in my simplistic understanding of things, sounds kinda familiar.

Daumier and the publisher were imprisoned in Sainte-Pélagie prison for six months and heavily fined as a result of this single cartoon. Incidentally, it is worth noting that Philippe Honoré, one of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists murdered on January 7, 2015 had, in his very name as well as his art a connection to the Honoré Daumier/Louis-Philippe conflict. La Caricature didn’t last much longer after the imprisonment of its principals, but Daumier went on to become one of France’s greatest and most beloved caricaturists.

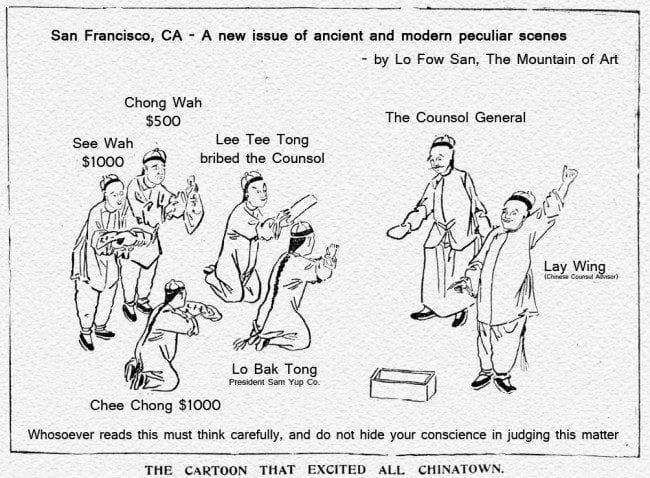

Sometimes, cartoons act as a kind of social dynamite, exploding tensions that have been building up underneath for some time. When a cartoonist finally puts pen to paper, the results can be both powerful and poisonous. Consider the case of the 1895 cartoon signed by a cartoonist with the impressive moniker of “Low Fo San, the Mountain of Art.” I suspect “mountain of art” was meant to suggest strength and determination, rather than quantity – a characteristic that seems to possess and embolden cartoonists from time to time.

Back in the days of 1895, things had been going South in San Francisco’s Chinatown for some time, as the sub-city’s rigid internal social and economic structure was falling apart due to corruption. On August 4, around one o’clock in the afternoon, the Mountain of Art’s cartoon was posted on a deadwall at the corner of Clay Street and Waverly Place. The cartoon depicted the Consul-General accepting bribes to free a man accused of murder. Damning and angry, the cartoon named names and pointed fingers.

“Confusion reigned in Chinatown,” the San Francisco Call reported the next day. “Within thirty minutes of the time the See Yup artist displayed his caricature to the public fully 5000 Chinamen were fighting to get near enough to see it.” The cartoon incited a near-riot, and all night long the police and the Chinese community were at war. Let’s see. An ethnic community takes to the streets in outrage over an injustice involving a freed murderer and battles the town’s police. That sounds familiar. But the point here is that it was a cartoon that put the match to the fuse.

History is filled with instances of politicians raging against purveyors of the pen. Recently, just two months before the Charlie attack, Ukraine’s Cultural Minister was reported to have demanded that a cartoonist be killed by a firing squad for making fun of her bizarre topless bikini photo shoot.

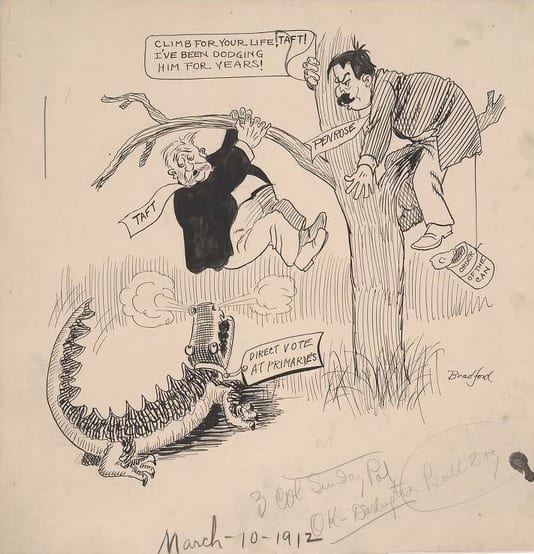

Looking back into the past, it’s easy to find examples in American history where cartoons have provoked the outrage of politicians. For example, there’s the 1908 conflict between John E. Reyburn and the cartoonists of the Philadelphia North American. The language of the charges resonates with red-faced anger as it takes offense at: “certain cartoons containing and intending to injure, oppress, defame, and vilify the good name, fame, credit, and reputation of the Mayor,” and to “bring him into public infamy, contempt, and disgrace.” Well… sure. It seems pretty clear that this was absolutely the point.

The Mayor’s attorney paid a lot of lip service to freedom of the press, but in the end, all he managed to show was that he regarded this freedom to be a good thing, except when his client was attacked: “… but it seems to me the time has come to ask the courts to determine whether or not, under the right to criticize, there shall exist and be practiced without restraint unlicensed abuse upon the individual life of the official.”

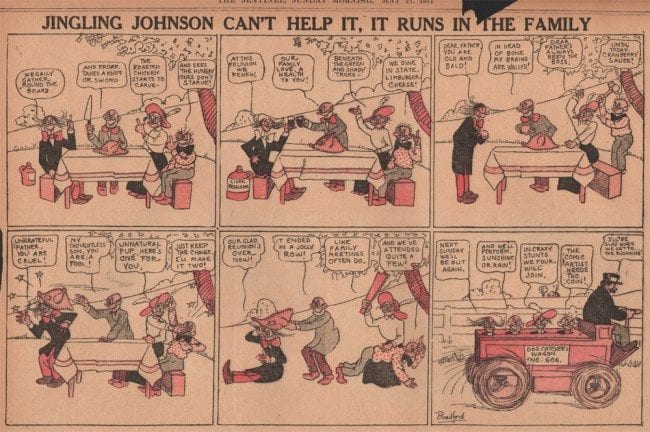

The objects of the Mayor’s retaliation included cartoonists Walt McDougall and Walter R. Bradford, both of whom created a notable body of work in humor comic strips. W.R. Bradford’s comics posses a glistening sense of comic anarchy, as potent at the disruptions of the Marx Brothers. After tackling political figures and bomb-tossing anarchists (Fizzboomski) in his early years, Bradford moved on to drawing comedy in less volatile, but just as rich, subject matter, such as henpecked husbands (John Dubbalong), insane families (The Peaceful Pickleweights) and, in one what may be one of the great forgotten humor comics, mad poets (Jingling Johnson). In Jingling Johnson Bradford turned the power of caricature on himself, modeling the compulsive, chaos-creating verse spouter on one W.R. Bradford.

The astonishingly prolific Walt McDougall became one of the most well-known and powerful cartoonists of his time. He drew a number of genuinely funny and anarchic humor comics, including Fatty Felix and the Flipp Boys, Hank the Hermit, and Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz (written by Oz creator Frank Baum, and recently reprinted in a glorious Sunday Press edition). It is sometimes written that McDougall was bribed to leave town in the 1904 elections, to give politicians a chance. In 1938, at the age of 80, McDougall took his own life. One of the last entries in his diary read: "Stove won't work -- hard times."

In 1926, Walt McDougall published his autobiography, sardonically entitled This is the Life, where he briefly detailed the events of the Philadelphia’s mayor’s attack on the local cartoonists: “The differences between the city administration and the virile North American had grown so pronounced as to be almost savage.” McDougall explains the mayor was an infamous evening partier, and often spoke so incoherently that it created “the belief that he was intoxicated.” McDougall created a series called The Reyburn Night’s Entertainment that provoked the Mayor’s outrage. It turns out that the Hon. Mayor Reyburn’s charges were fairly commonplace, as McDougall states that it happened “about once every fortnight.”

In once such instance, the McDougall and Bradford were summoned to a hearing which, “owing to the intense heat” lasted a mere two minutes. They were released on bail and no further proceedings were reported.

The net result of the Mayor’s attacks was that the North American became stronger. As McDougall wrote, “Even if the paper won no political victories, it established a reputation for high moral aims, vehement rectitude, militant municipal purity and general uprightedness…”

As a comics historian, I am constantly tripping across two kinds of provocative cartoons: those that were designed to deliberately and consciously attack power, and those that less consciously prop up a status quo of de-humanizing a particular group of people. The former, we occasionally celebrate. The latter, we tend to, thus far, sweep under the carpet. Art Spiegelman, in his Democracy Now appearance, pointed out, for example that, while our culture has canonized Thomas Nast for his cartoons attacking the notoriously corrupt New York City government of his time, we rarely mention his anti-Catholic cartoons, such as the one where the papal officers are portrayed as devouring crocodiles.

Both kinds of cartoons – those that use ridicule and mockery to challenge those in power, and the deleterious ones that casually put down people are a part of our history and the essential lineage of comics. I would argue that it’s a good thing that we folks of 2015 can look back at a 1920s comic strip portrayal of a black American and feel a sense of collective embarrassment. I would also argue that we should not pretend the comic didn’t exist, and skirt around such things in histories and popular accounts.

In my work with various comics history writers, editors and publishers, I regularly encounter a kind of collective self-censorship which avoids reprinting and discussing the old racist, ugly comics as much as possible. It’s a very difficult issue with which to come to terms. After realizing how many professionals in my industry have suffered and even died to be able to do their jobs, I am wondering if maybe we could do with a little shot of truth, even if it hurts.

When I was working as an editor and writer on The Art of Rube Goldberg (Abrams ComicArts, 2013) I had a large influence on the selection of material for the book, and in fact over one-third of the content comes directly from me. Here’s one of those “sweep-under-the-rug” cartoons by one of the grandmasters of American comics that are in my collection which I self-censored, and didn’t even think of publishing:

Rube regularly portrayed ethnic stereotypes in his work, like most of his contemporaries. These portrayals of heavyweight champion boxer Jack Johnson are embarrassing by today’s standards, but Rube Goldberg actually admired Johnson. In fact, in print, he publicly picked Johnson to win the famous “fight of the Century,” when the former champion, who happened to be white, came out of retirement to defeat Johnson; the so-called “great white hope.” Rube picked the winner: the black champion won.

And yet, around the same time that mainstream American newspapers perpetuated degrading racial stereotypes as a matter of daily entertainment, the American system allowed for those picked on to speak up for themselves. One instance I have found is the remarkable series of cartoons published in the Washington D.C. edition of The Colored American, which ran from 1893 to 1904 and was distributed nationally. Around April, 1901, the paper began running merciless cartoons attacking racism against black Americans. I have found nothing on the cartoonist, other than his name: Freedom W. Hoffman. It’s not clear who wrote these cartoons, but I admire their bold, outrageous nature. It’s a sort of tonic for me, after reading endless comic strips portraying black people as sub-humans.

It’s interesting to consider that Goldberg himself was a non-practicing Jew who stubbornly refused the suggestions of his gentile colleagues to change his own name to get ahead, and got the last laugh when his very name became an official word in the American Heritage dictionary. Nonetheless, Rube bowed to pressure at the start of America’s entrance into WWII when he had left his career of humor cartooning far behind and was drawing editorial cartoons for the New York Sun. He was receiving death threats for his cartoons, and at the same time, news of what was happening to Jews in Nazi concentration camps was surfacing. So Rube insisted his two sons change their last names. And they did, moving from “Goldberg,” to “George.”

This column picks on Rube Goldberg not because he was any worse than his peers, but simply because its author happens to have reams of research on Goldberg handy. One could dig through the life and work of most American cartoonists of the first half of the twentieth century and one could find examples of casual racism. You won’t see much in the current tomes filled with reproductions, but when you sift through the old newspapers, magazines, and comic books, it’s unavoidable.

Comic books of the 1940s are rife with racist stereotypes, including inhuman portrayals of Germans and Japanese during World War II. Even the great and humane Jack Cole - whose high school parodies also nearly got him expelled, jumped on this wagon.

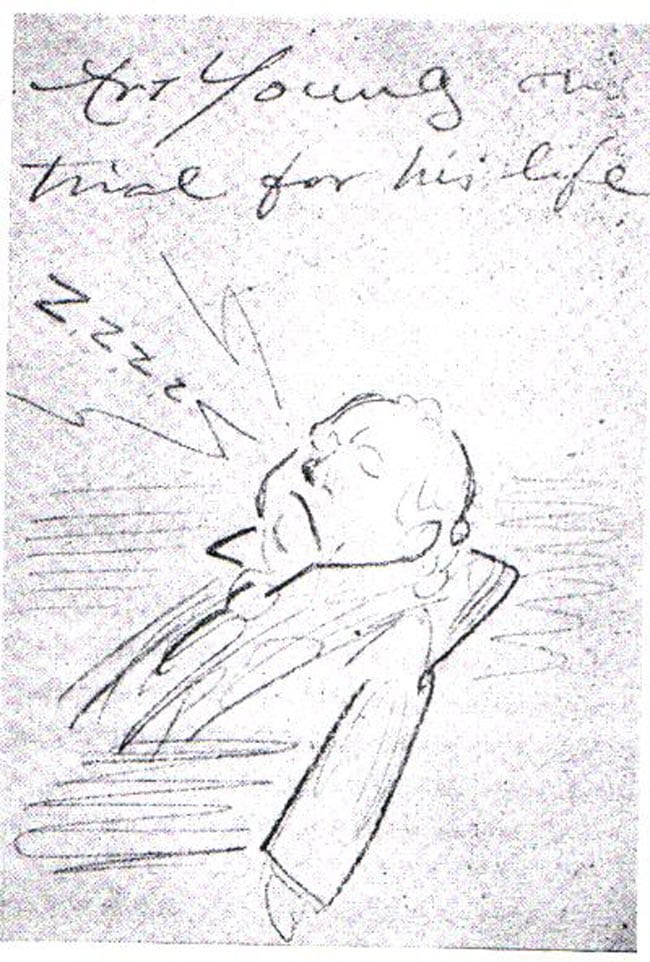

And speaking of great and humane cartoonists, it’s worth mentioning Art Young, the socialist cartoonist associated with The Masses. As with La Caricature, several members of The Masses, including Art Young were put on trial under the Espionage Act for their anti-war cartoons. Young, afflicted with a propensity to nap, drew a cartoon self-portrait of himself that was truthful and mocking:

Every time I look at “Art Young on Trial for His Life,” I see the joyful mischievous grin of Bill McAndrew. Whether it’s my old friend’s unpublished satires of the people in his orbit, a cartoon posted on a building wall that causes a near-riot in the streets, an angry politician suing pen-and-ink satirists, an outraged king imprisoning a caricaturist, or a group of religious zealots gunning down cartoonists in cold blood, there’s no doubt about it: there is a strong and deeply satisfying impulse in the cartoonist to ridicule and provoke that will not be suppressed.

Bill had a few hard knocks in his life. I know of a few, and suspect many more. One day in Tallahassee, when he was out of his house for a short while, a man entered his home and brutally raped his partner – an event that haunted the couple ever after. The last time I saw Bill McAndrew, he accompanied me to a grocery store. All he could afford to buy at the time was a single tiny jar of baby food. Proud, and driven by some internal pressure I couldn’t fathom, he wouldn’t take any money from me. A few years later, in 1992, Bill died from a brain tumor. I miss him. I wish he were around today and that he would have made a new merciless, smart-ass caricature to show me. And then we’d laugh.