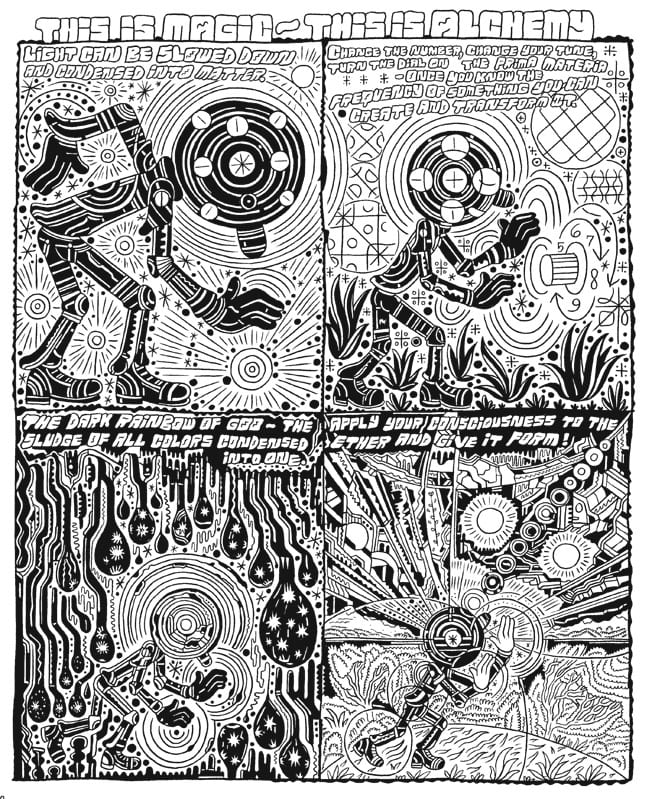

Ron Rege Jr. was born in 1969 and grew up in Plymouth, Rhode Island. He broke into comics at age 5, and has been bending them to his will ever since in an unending flow of radiant pen-and-ink. Lifted out of ‘90s Boston DIY mini-comics legend/obscurity and into actual published book world by the championship of sainted Tom Devlin (first thru Devlin’s Highwater imprint, which published Rege’s bizarro fable Skibber Bee-Bye in 2000, then via Devlin employer Drawn & Quarterly, which published 2006’s The Awake Field and the 2008 Against Pain collection), Rege has spent the last few years doing random jobs of commercial artwork, playing drums in the on-again, off-again cosmic-peace folk-rock band Lavender Diamond and, most important for our purposes here, immersing himself in the world of Western mysticism—Esoteric thought—New Age stuff. Usually that way madness, delusion and life-damage lies. And indeed, a casual paging through The Cartoon Utopia, Rege’s just-published 148-page hardcover survey of dozens of major occult thought-streams in words-and-pictures form, shows not just a radical transformation—heightening?—in Rege style, but also a degree of... Yikes! Has Ron gone crazy? The trademark Rege cuteness is still there in the human figures, but there’s no narrative, no word balloons. Instead: cascading masses of block text drawn in 3-D profile, cross-sections of micro and macro-cosmos, action squiggles and diamond zaps, chromosomes and galaxies and plant leafs and on and on—a spookily obsessive, vibrating crunchola that recalls Egyptian and Mayan hieroglyphics, ‘70s Jack Kirby at his trippiest, Howard Finster’s folk-Christian exhortations, and, of course, every genius featured in the landmark 1986 LACMA show catalog, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting, 1890-1985. If that sounds like too much—it is! Rege himself advises that The Cartoon Utopia should not be read all at once, or even in any particular sequence, which begs the question: how did he survive making this beautiful, deeply weird thing in the first place? To find out, I left my Joshua Tree desert home in late October and ventured back into Los Angeles, where I’d first met Ron in Fall 2003. Over cups of hot green tea in his cozy Echo Park apartment, we circled the atom heart of the matter. Here’s some excerpts from our conversation.

Jay Babcock: When did you come in contact with Maja D’oust, whose lectures on occult subjects form the basis for the book?

Ron Rege Jr.: She knew Sammy Harkham years ago. I think I may have met her for the first time from him, or just from around, from cartoon people in L.A. I vaguely knew that she worked at the Philosophical Research Society but I didn’t know what it was. I knew she had done these shamanism lectures and I was like ‘I gotta go I gotta go’ and I didn’t go.Then she was doing a series called Alchemy and Relationships,’ which I decided to attend. I walked into this place and I was like I don’t know what this scene is gonna be and I look around and half the people there are in bands that I already knew in L.A. All of these people are here listening to this friend of mine?!?

JB: When was this?

RR: This was around Christmas 2008: Lavender Diamond stopped playing, me and Becky [Stark, Lavender Diamond’s singer] had broken up. I went to see my family, came back to L.A., saying what the fuck am I doing here? Who do I even know in LA anymore? No one. Who are my friends? What the hell. And went to Maja’s lecture.

JB: Ah...

RR: So, after one of her lectures we hung out for a few minutes, and she was like, ‘Do you wanna go see [Philosophical Research Society founder and scholar/author] Manly P. Hall’s library?’ And I went in there and I said something about one of my books, and she was like, ‘Yeah I’m a big fan of Skibber-Bee-Bye. You made this great abstract graphic novel about the shaman’s journey.’ I had no idea what she was talking about. I was like, What do you mean? I look at it now and it’s like, yeah, that is what it is. I had no idea. I always had this kind of philosophical yearning in what I was doing...but I also don’t feel like I invented what these characters are and what they do [in Skibber-Bee-Bye]. I feel like it was kind of dictated to me. In a way. NOT in a direct way like I went into a trance and channeled it. It wasn’t like that. But, I think that’s kind of what it was.

JB: What did you think you were doing when you were making it?

RR: At the time, I didn’t really know. I wrote it all before I drew it. I really think of it as being channeled, in my way of understanding things now. I didn’t make any ‘decisions.’ I see a lot of cartoonists making works now and they’re trying to make a movie, make some plot structure that makes sense. I’ve never had any interest in that. I wouldn’t change what I’ve written. It just came to me and I wrote it all down. I wrote it in script form, like ‘she does this, and then this, he looks at this,’ and actually...

JB: This took about...

RR: About five years.

JB: When did The Cartoon Utopia start to take shape? I remember you were doing residencies around that time...

RR: I did a week residency in Vancouver Island. And a residency in Montreal, in 2008. The trip to Montreal was when I started doing the stuff that led into what this is. I was frustrated with comics. Didn’t know what I wanted to do anymore. Didn’t want to draw regular comic strips. Didn’t have any ideas for characters, stories... Oh, I’m DONE. I’m not going to draw comics anymore. I’m done with comic strips, I’m done with narrative. Maybe I’ll start doing fine art — so I started doing all these big drawings. I had taken the Process Media biography of Manly Hall with me on the trip and was reading it on the trip. WHAT?!? Finally understanding him and what all this stuff was and was kind of using that inspiration to make these big pictures, all the ones that are in the beginning [of The Cartoon Utopia - pages 8, 9 etc]. I did these in Montreal. Talking about serendipitous stuff: I was getting this idea of, ‘What is alchemy?’ That’s part of the biggest shift in my consciousness, going from one kind of way of thinking about stuff to another. From, ‘Oh alchemy is this stupid shit from the past that was about turning lead to gold. It’s this backwards stuff from before science’ to ‘Well, oh no it isn’t, it’s to do with a lot more than that. It’s the basis of everything, that informs everything.’ It seems like a pretty simple thing to understand but it’s a big jump for people to think of it in one way or the other.

Serendipitous things happened in Montreal. I was walking down the street and I saw this little paperback lying in the middle of the sidewalk that said ‘Alchemy!’ on the cover—really dry, all physical alchemy, but there it was. And I was actually thinking about [alchemy] at the time! The book was all dogeared and taped together like it’d been read 10,000 times. And this was in a desolate, warehouse-y part of Montreal. I was like Okay, this doesn’t belong here, I’m not taking this from anyone, it’s lying on the sidewalk, it’s gonna get blown into the gutter in half an hour or rained on or something, so I picked it up.

JB: Whoa...

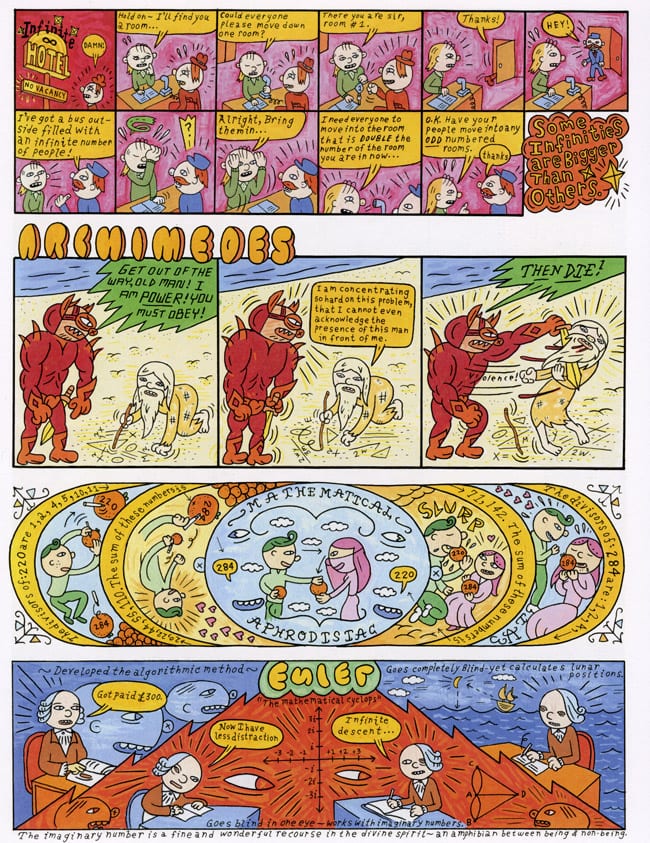

RR: But really, The Cartoon Utopia, in the way that it’s done, is an extension of one story that I did called “We Must Know/We Will Know” that I did for the Drawn & Quarterly anthology. It’s pretty much an adaptation of a book I read all about math called Fermat’s Enigma. I read the book and highlighted parts that I thought were interesting. It’s ten pages of short individual pieces that all fit together as a whole. And the way that I did this, of taking something that was academic, or, you know, even though it’s a ‘popular science’ book but it’s somewhat academic, and turning it into a comic strip, is what [Cartoon Utopia] is. I started going to Maja’s lectures and I started reading 10,000 esoteric books, highlighting them the entire time, and wove it together. So, this is an extension of this approach to cartooning...which, I didn’t realize it, but Sammy Harkham wrote this piece recently saying that this is actually a pretty standard way of doing comics now: doing a whole bunch of stories that equal up into a story. And I did it first...?

JB: Well, you did it there, at least.

RR: Sammy says that I invented it. [laughs incredulously] And he wrote a little article about it. I feel weird saying it but when I did this, I didn’t really think a lot about what I was doing, but I definitely didn’t get the idea of doing this from anyone else. And I had never seen anyone else do it.

So I guess I was the first one to do it? Which seems weird now, cuz there’s a lot of people who do stuff that way. And I don’t think that Clowes was thinking about what I did when he did... It’s just having the same idea at the same time, of a way of approaching comics.

But yeah, that story is how I ended up, it’s like that desire, ended up [being] how I did this thing.

I’m curious what the comics world is going to say about this book, how this is ‘comics’ at all. I did this on purpose. Because I love comics. The nerdy discussion of comics that has gone on for the last decade has always been something that’s been super-important for me. And I DEFINITELY did this on purpose, as far as that regard goes. I KNOW that there’s no word balloons, and there’s no characters, and... Part of doing this, besides just being inherent for me, was just being about pushing the medium as far as I’d already pushed it, pushing it even further, and making it specifically my own. Not like I had to fight it, it was a natural progression, but it was definitely on purpose. How can I take this form and make it my own voice, truly and honestly, in the way that I want to do it, in a way that’s exciting to me, that’s really far away from the traditional narrative sense of the medium. But it’s still words and pictures together.

I'd like the book to be viewed as a kind of textbook, that's it's not meant to be read and absorbed all in one sitting. People should use bibilomancy—randomly opening to a page—to access the information if they'd like. Nothing in the book tells you to treat it that way, but I think people will get the idea anyway.

JB: I have a very specific memory of being at your and Becky’s place and seeing your sketchbook and saying Ron, you need to pursue this visual style on a bigger scale, it’s really great. And you said Oh that’s just what I do when I’m not really working. I remember saying, Maybe you should try doing that when you’re really working! I don’t remember what you said.

RR: [laughing] I was probably dismissive!

JB: I think you were probably already headed in that direction. That, to me, watching you kinda shift, bringing that aesthetic into your to-be-published work, is the real breakthrough in this book...

RR: Which is true.

JB: That seemed to happen around...

RR: 2008.

JB: Remember when you did the ArthurBall poster artwork? In 2006. I hadn’t seen you do that for published work before... I’m not saying that was the first time you did that, I’m not sure.

JB: Remember when you did the ArthurBall poster artwork? In 2006. I hadn’t seen you do that for published work before... I’m not saying that was the first time you did that, I’m not sure.

RR: But it was, really! It’s here. [Point at endpapers for Against Pain] This is... To me, it looks kind of amateurish. I would be like, Yeah this is just junk, this is just me goofin’ around, trying to do fine art or something like that. This, to me, looks like really undeveloped versions of everything that’s in here. Like, I hadn’t quite figure out where the squiggles go yet. I was just starting.

JB: In 2008...

RR: I felt that I had exhausted comics. I just started doing... I ruled out these square panels, and I just had a pile of them. I just started doodling on them. It was just a way of producing a lot of work and I thought I could sell them. Ad I must’ve because I don’t have any of them anymore. I sold some at the Hope Gallery show. And basically started doing it, doing the whole Cartoon Utopia idea, because I started putting words into them. Slogans. Under the Becky influence, and Lavender Diamond. At the height of that. And just, all of these things at the end of the book: Utopia! I talk about, We can have Utopia now! They must learn the ways of Peace! I just started making panel after panel.

JJ: For the “Peace Comics” strip we ran in Arthur by you and Becky, you were using your old style but you were using these ideas...utopian ideas.

RR: The Cartoon Utopia. I don’t know when I came up with that word, but it’s a good catchphrase for everything.

JB: You had a real clear idea for this book. I remember you saying you always saw it as a book.

RR: I went directly from those panels that are at the back of the book, that are like these abstract things, and then I started doing these all in the front... [pages 15, 16, 17] The first five pages are from the first two lectures of Maja’s that I went to. I was just doing it panel by panel. And then as I started reading the books and highlighting, doing it panel by panel, I was like, THIS is what I want to do with comics! Alright, I’m FINALLY interested in comics again! It’s words and pictures, there’s no characters, there’s no storyline, but I felt like there’s this information that I’m SUPER excited to present with words and pictures put together. I don’t know if it’s comics, or what it is, but I’m just gonna do it. And I was fascinated, to this day, of doing it that way. Instead of doing it panel by panel, yeah, I slowly started breaking it up into page-size stories and then had them all laid out.

JB: There’s an awful lot of stylized text. When you look at the book, do you see lettering or art?

RR: I see them being pretty inseparable. What do you mean?

JB: You spend so much time and space on lettering per page! The amount of text design per square inch...

RR: Yeah that’s true.

JB: You hand-draw each letter. And they’re not letters —they’re outlines of letters, so there’s even more work.

RR: Yeah exactly. I actually did them really quickly. It is a ton of lettering. I don’t think this book can be published in another language. I was about halfway through and I was, What a fuck-up! Cuz nobody can re-letter this in another language [laughs]. If they want to re-letter this in another language, I don’t know how they’re gonna make it fit. Cuz there’s no extra space... I feel like if somebody wanted to re-letter it, I just could never look at it, because it would make me insane, cuz it wouldn’t fit.

JB: What was your process for this book?

RR: I did the lettering first. I would grid out the pages, and I would put the lettering in and then I didn’t know what the images were. The entire book was done, the panels with the words in it, without having the slightest idea. [looking at pages 81-83] Oh look, I did this one at your house! Like this one, for instance, I would’ve brought this to Joshua Tree, had no clue what was to be drawn in here. And that’s what, like every week, I’d be like I have to do these four pages this week, what the hell is gonna go...? Having not read the material in a long time, cuz it was all done out a year in advance, I would just look at it and then I would slowly... I knew what it would say. But how to visually represent this? I didn’t know beforehand. I just knew the information that I wanted to relay, and I had to figure it out, and in that way I ended up doing things where this is actually the same character and he goes through to page 82, 83... There are characters that come through that were just invented for a short space.

JB: The Fantagraphics promotional text for this book does make a small attempt to say that there is some kind of narrative to this. “Beings from the future” etc.

RR: [laughing] That’s based on this page only! It’s a little bit of a ploy, and I think it’s a great ploy, to get people who like comics to pick this up. I don’t think I’m really going to be fooling anybody, but what the hell! I did want to do a graphic novel, a cartoon utopia, with beings from the future living... I was going to have them all living on a mountaintop, and maybe I’ll still do it, I kind of doubt it, where they’re living in a mountaintop but then there’s a post-apocalyptic Idiocracyland happening down below. There’d be all these higher consciousness people above... but I don’t think I’ll really do that, because now I view that kind of... I don’t know what the word would be...

JB: Elitist?

RR: [laughing] Yeah exactly. Elitism in looking at humanity, which is prevalent in so much of this material.

JB: A lot of the book is exclamations, affirmations...

RR: Yeah, exclamations and affirmations, intensely, one after another. For 150 pages. It’s kind of hard to take, I would think. [laughs]

JB: And then exhortations, like “We must... / We need to...”

RR: Yeah it’s kind of rallying up the troops or something like that. A pep rally. Whether I personally feel that way doesn’t really matter. [laughs] Anyone who knows me personally will know that on some days, I feel that way.

JB: It’s also just simply a survey of what you’ve been reading, without judgement.

RR: Lavender Diamond and this book have the same view of creating artwork. Really intense, positive reinforcement of a positive message. Being unrelenting in that aspect of it. In reaction to all culture that I’ve been exposed to my entire life. To just try and make something different. And the negativity of that just becomes so inherent that I don’t see anything being produced in any medium that isn’t so inherently negative—there doesn’t even seem to be like any alternative to that anywhere that I look around and see.

JB: You started into this vein with Becky, Jim Drain, Peter Glanz, Pshaw, that whole gang... That whole enthusiasm, brightness, positivity, humor, playing with the idea of corniness... seemed to me to hark back to what the Pee-Wee Herman TV show was doing.

RR: Definitely, yeah. I look back to it being tongue-in-cheek but also being sincere. Are you REALLY being sincere? The most important thing to me is trickery, in all aspects of art. The opposite of being confessional or autobiographical is to present this stuff in a way that almost makes people question your sincerity. Because it’s so intense. Which to me is a little bit of a trick, y’know?

JB: Just because it puts them into a space of...?

RR: Yeah. Opens them up and puts them into a state of like...wonderment. Of confusion.

JB: Which you think is inherently helpful...?

RR: Yeah, I think the best art slash entertainment is meant to dazzle you and spellbind you into being in that state. It’s really supposed to spellbind you and hypnotize you into being in a certain space to be taken into a fantasy.

JB: That would be the work of a trickster, or shaman, in some sense.

RR: Yeah, definitely. But I feel like I came into it without even knowing that’s where I was going! [laughs]

JB: Do you feel like you’re a solo practitioner of it, or do you feel like you’re part of a fraternity?

RR: NOW I feel like I’m part of a fraternity. But yeah, I felt like I was a solo practitioner for most of my life [laughs] and then I met Becky and I felt like she was the only other person I’d ever met who was into that. It doesn’t seem as weird, anymore. All of a sudden, just in the last few years, I feel like there’s a lot of things that are happening that have this similar message. So it makes me really happy to have this book come out right now, where I don’t feel alone at all anymore — I feel like there is a vast network of people that are approaching creativity in the same way.

JB: In LA, that would be people like...

RR: Gosh, it’s hard to even say, specifically. People like Mira [Bilotte, of White Magic]. Alia [Penner, artist]. Guy [Blakesleee, of The Entrance Band]. I’m just naming all the people that go to Maja’s lectures with me! [laughs] But then I feel like there’s a lot of musicians who I don’t even know whose stuff, like Cameron Sun Araw, he’s someone who, when I met him, and just talked to him for five minutes, I realized, Okay you have the same basis to what you’re doing, and you’re putting pyramids in there and stuff, it’s not just fashion, why you’re putting that content into your work. This isn’t a fashion—using occult symbols in what you’re doing.

JB: This stuff has been in comics forever, and in a lot of major work in the last 20 years. I know I can say but Ron, you were never alone, not even in comics! There was Jodorowsky and Moebius’s Incal series. Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles. Alan Moore and JH Williams’ Promethea. But you never read any of that stuff.

RR: No, not really. I would’ve been out of superheroes by then and it’s hard for me to LOOK at that stuff now. And I LOVE everything that those guys do, without necessarily being that familiar with their work. Every video I see of Alan Moore speaking is an enormous inspiration to me.

JB: You don’t judge the stuff you cover in this book.

RR: A lot of people of my age, or a lot of people in general, dismissed this stuff a long time ago. I for some reason just hadn’t come across it until I was however many years old. [laughs]

JB: You never say like, You know what? I’m not really down with this guy, or so-and-so makes a mistake here. Or, this isn’t very useful. Or, we now know this is caused by... There’s no critical analysis. You just kind of present the stuff. You remain in a state of not taking a side...

RR: Yeah. That ties into the idea of seeing alchemy for what it really is. Because if I’m going to talk about the fact … what the fuck was wrong with Tesla? I read the biography of Wilhelm Reich, and oh, this whole idea of tying the orgasm to the aether is amazing, but it sounds like he was an alcoholic that beat the shit out of every woman in his life. Those are the stories that are used to dismiss the work that all of these people did.

JB: That’s true, but there’s also stuff where it’s just like, dude, that’s a nice theory but it’s wrong—that’s not an aura, that’s just your eyes getting crossed.

RR: Yeah, I wasn’t interested in that. I was more interested in the magical, inspirational part of it that’s positive.

JB: Almost all of the book is borrowed wisdom.

RR: Almost all of it, yeah.

JB: It’s not experience of Ron Rege.

RR: There’s some very small parts that are mixed in.

JB: Why isn’t there more experience of Ron Rege?

RR: Because in the process of making this I was just so overwhelmed with all these other ideas that were brand new to me. I just felt like I wanted to tell everyone.

JB: “Hey, this exists. There might be something here for you that will send you in a positive direction.”

RR: Yeah, pretty much.

JB: What happens now? You’ve surveyed all these things. What conclusions have you drawn?

RR: I thought when I was doing this that I would be doing these kinds of comics forever, because the more I would get into stuff, the more there was that I wanted to do. There is more of what I’ve experienced that I want to put into them, but I had to cut if off to make it a book. Cuz this could have been a three or four hundred page book and would’ve taken another ten years doing this. But I knew, I gotta cut this off.

JB: Where do you see your personal spiritual practice going, outside of art?

RR: I don’t know right now. I’m at a point of mystery with it, at this exact moment.

JB: But you don’t find yourself drawn to a certain school, or lineage? Or... ‘you know what, I think it’s really the Alchemists for me.’

RR: No, I don’t.

JB: Like, ‘Now I really want to head to the east...’ Or, I want to go deep on this one.

RR: No, I don’t think there’s any one in particular that I want to delve more into. I wanna keep being open to all of the different aspects. I didn’t attach to any one. I’m not like gonna get into Zen now, or any particular one. From what I know, there’s probably even more obscure aspects that I’d like to look into, but I still am very generally fascinated by the wide gamut of everything. And I want to keep that enthusiasm. To me, it’s important to not pick one little thing. If anything, it’s about the unity of everything and everyone into one thing. It’s weird to me to go and talk to somebody who’s into one thing and doesn’t know about another thing. To be like this weird little section. Which seems weird because it’s all so interconnected.

JB: What about going beyond belief and speculation? What about practice?

RR: That’s something that I definitely struggle with. I don’t have a very great practice of anything. My practice has come through my personality and the way that I approach other people, and deal with other people, and then issues with my life. I’m very interested in my dream practice right now: the differentiation between waking life and sleeping life.

JB: You have a strip in there about the Tibetan dream yogas.

RR: Yeah. But... I definitely am going through a period of really ultra fascination with everything. Life seems like — and I don’t know if it’s the life that I’ve created for myself, or if it’s just experiences that I have — I’m just fascinated all the time. The lights look brighter. The colors on the trees look more green. The things that people say seem way more significant. The vibes that I’m getting from people...the give-and-take, the push-and-pull with other human beings. And then I’m just amused and fascinated by they way that people act. Usually if I go out in a social situation, at one point during the night I’ll be just like, ‘Humans are ridiculous creatures! Just ridiculous!’ And I’ll think about all the interplay in social structures, different people I know — just what we’re eating and drinking, and the way that we’re... I feel like I’m a squirrel [watching the humans]... Suddenly I have this weird awareness of how utterly ridiculously fascinating everything that we’ve created is.

JB: Like a continuing elevated consciousness?

RR: Yeah, I definitely feel like I have a richer consciousness, but as far as practice goes... I don’t have very good meditation yoga, or even diet, or those kinds of things. That’s probably an aspect where like maybe it would be good if I picked some specific practice to follow because I’m all out there with all of it.

JB: The other thing a shaman — not necessarily the trickster — does, traditionally, is heal...

RR: [pauses] I think that we’re all trying to help. I’m hoping to help awaken people through doing this [book]. I think that Lavender Diamond is the same way. I feel like most of the people that I know that create art are pushing their stuff in the direction to awaken people to what they might recognize in themselves.

JB: You’ve made a tremendous sacrifice to do this work. It’s not like it’s lucrative.

RR: That’s true.

JB: These last few years haven’t been easy for you, I know. Anyone who’s followed you knows that you didn’t have a book contract. Last year, you directly asked for patrons on your website and through Facebook, which worked to a degree...

RR: It’s funny, it’s such a story of how comics get made. Cartoonists talk about it a lot, but [usually not in public]... I definitely sacrificed a lot to do EXACTLY what I wanted, to do this. And then, to have it rejected [by the first publisher I approached]. Everyone at Fantagraphics has understood it and has been really supportive of me doing exactly what I wanted to do. They gave me a blank check to do exactly what I wanted because obviously I had a mission, I wasn’t just fucking around, and based on my previous work. They just let me do whatever I wanted. Cuz it was all gonna come down on me.

This material, and working on this book, yeah, it’s definitely been a difficult time in my life for sure. On a personal level, financial level — midlife crisis, ground zero, starting over. This book definitely comes from a time in my life of upheaval. Everyone probably experiences it in different ways, it’s pretty common. It’s not ‘I got divorced and lost my job!’, but [laughing] you might as well just think of it that way. Yeah, “I turned 40 and had zero dollars in the bank, a bunch of debt, got divorced and lost my job!” I didn’t [literally], but it was totally like that. Yeah, I completely lost, and then...made this. And if I didn’t have this, God only knows what would have happened to me.

JB: Well I’ve seen how focused you’ve been on doing this for these last few years, in spite of other difficulties. You’ve kept it very together. And I think that’s important to note, because I think when people look at this book, after they see the beauty of it, they also go... [whispering] “Has Ron gone crazy?” This looks like the work of a crazy person or a person who’s suddenly started taking very heavy psychedelics.

RR: I was really worried about that—

JB: But you are not a crazy person, you’re very focused—

RR: And I’ve never taken psychedelics. [laughs]

JB: How is it possible you’ve never taken heavy psychedelics?

RR: I don’t know. [laughs] Cuz I had too much work to do? Yeah, I also look at it like this was my self-therapy. My “escape,” my “shelter,” my “running away from my problems,” my “not paying my bills, not answering the phone,” was the fact I was doing this. My self-therapy was creating this work. And it could’ve just easily been playing video games and getting high or something like that. For some really great reason, my therapy — my way of getting through it—was creating this work. I feel super-blessed and lucky to have that avenue, to have the insight [to do that]. I could have made a bunch of shitty work that was completely disjointed or didn’t have any value to it or something [but I didn’t].

JB: I still feel like you’ve hedged your bets a little on this book.

RR: [laughs]

JB: Because so much of it is others’ words, and ideas!

RR: Mmm hmm...

JB: Which is totally fine, and totally good, and a totally worthy book... but what will happen when you take that approach of … when you push the medium... I think you’re going to need to put yourself out there a little further in order to reach the next level of what you’re capable of. I really see this as a transitional work! An EXCITING transition. I see so much formal experimentation, so much clear enthusiasm and excitement, on every page. It’s so obvious that this is a work of real devotion. Those are levels rarely seen. But: you haven’t done, except in a few pages, the William Blake saying — “If a man doesn’t make his own system, he’s a slave to someone else’s.” Or the Howard Finster, or any number of people who have...

RR: Yeah, that’s true.

JB: I think that’s what a lot of us want to see...next!

RR: That’s why the next thing I have in line is more in this direction [points at new work, set for publication in Abraxas].... but maybe I won’t end up doing it.

JB: Sun Ra is in the new book. Now that’s not one of the things you were introduced to by Maja...

RR: Sun Ra is not new at all to me. I’ve known about Sun Ra for 25 years! I liked his music from the musical aspect, I liked his performance from the wackiness of it. I liked him the way I Iiked whatever weird shit that I’m into — Butthole Surfers, etc.—Sun Ra is one of those things. ‘He’s a crazy black guy that thinks he’s from space!’ And yeah, I read his biography. But now when I go and look what he was talking about... Am I the one who’s crazy now because whatever speech Sun Ra is making is 100 percent what I want! And I hear EXACTLY what he’s saying and it doesn’t sound crazy to me at all. It sounds like the rest of the world is crazy. For 20 years, I was like, he’s just talking some crazy-ass space shit, whatever...

JB: Did you always conceive of this stuff in black and white, or color? Do you wish some of it was in color?

RR: No. I’ve always been a black and white cartoonist. The graphic aspect is so hard that even adding grey to it, it’s such another...universe. I’d like to maybe integrate color into my work and not use the computer. Because coloring on the screen with the computer, I can do it, but I’m not super-inspired. The idea of taking all of this work and coloring it on the screen, just would’ve deadened it. If I could integrate a little bit of color into my work in real life, maybe I would...

JB: You told me earlier this year that the Mayan artwork you saw at the LACMA ‘Children of the Plumed Serpent Show,’ you saw a similarity to your sutf...

RR: I’ve always known about that. At some point in art school [I recognized it]. But I never felt like that stuff influenced me. I was like, Yeah my stuff looks like Mayan art. It’s always been there. I’ve looked at codexes before and been like, WHOA, this looks like a language written in my style.

JB: I also see a lot of cosmic Kirby stuff in your comics — the abstract Kirby with the energy lines —

RR: Another guy I was never particularly into! [laughs] Even though everyone says that. I don’t know what it is. I never disliked Kirby, I always thought his stuff looked really cool. I’ve looked at his stuff but I’ve never thought of it as an enormous influence. I guess I only read the superhero comics that were coming out in the years that I read them. So I read John Byrne. I read Alpha Flight and The X-Men because that’s what was coming out between ‘85 and ‘87.

I’m not always interested in the stuff that’s really close to what I do. I don’t know if that’s common or not. It’s funny, I don’t know... Maybe this is the way of all artists? When I was growing up on Cape Cod, you could go and see Edward Gorey, he lived in a big Victorian house and we all knew where it was. If you were a teenage punk boy, he would really want you to come in the house and watch Baywatch with him. He was really into Baywatch!

JB: So what are you working on right now?

RR: I’ve been doing band stuff. I’m figuring out what I’m going to do next. I have an idea of what my next book is going to be but I’m not ready to start working on it yet.

What I’ve been super into lately is Jodorowsky’s Psychomagic. A year ago, I would’ve been like, Stop the presses! I gotta put in 20 pages about psychomagic! In this goddamn book. I want everybody to know about Psychomagic! Got super into the ideas and the practice of that, even separate from his Tarot stuff, anything else that he does. And the performance art tricksterish part of it. The book is made up of two interviews, where he contradicts himself continuously. You’re saying very adamantly the complete opposite of what you’re saying here that’s earlier in this book from ten years ago. Watching videos of the guy online, he’s always so excited. It’s just all a joke! And then him finally saying, yeah who cares if Carlos Casteneda is a big joke, and Don Juan didn’t exist? It’s nice, because I’ve heard people be inspired by it, and then deflate it, for like 20 years, and to have him suddenly be like, That’s not the point. Which is a little bit the way I’ve been approaching a lot of this stuff.

JB: One more thing that people might not know: how big an influence Yoko Ono is on you.

RR: The influence on me.

JB: I think it really comes through in the exhortations in the book.

RR: Oh, that’s cool! I’m glad that you see that.

JB: And she comes out of Fluxus, which you were into...

RR: Yeah, and why can’t anyone understand that? [Yoko’s art] is not crazy. Why is it such a big mystery...? I understand the whole shadow, her being presented as the whole Yoko/Beatles thing and that being reflected on her, if it didn’t have anything to do with that, there wouldn’t be this mainstream view... Seems like she’s been pretty clear and concise and direct with her message for her entire career.

JB: Which has always been one of...

RR: Positivity! Peaceful loving message without any irony or sarcasm to it— which blows people’s minds...still!

JB: You adore her. I have a great CD compilation of her music that you made for me. I think you were giving that to a lot of people.

RR: The pop mix. Trying to make a concise pop record out of all the gems that are buried.

JB: Another thing about your work: you’re so into women! [laughter] You had women teachers, gowing up—Catholic nuns. And then: Yoko Ono, Becky, Maja....

RR: [laughs] Witches!

JB: Do you feel like your work comes from a masculine point of view, or a feminine point of view? Or is that not a thing you think about?

RR: I think about it constantly.

JB: Really?

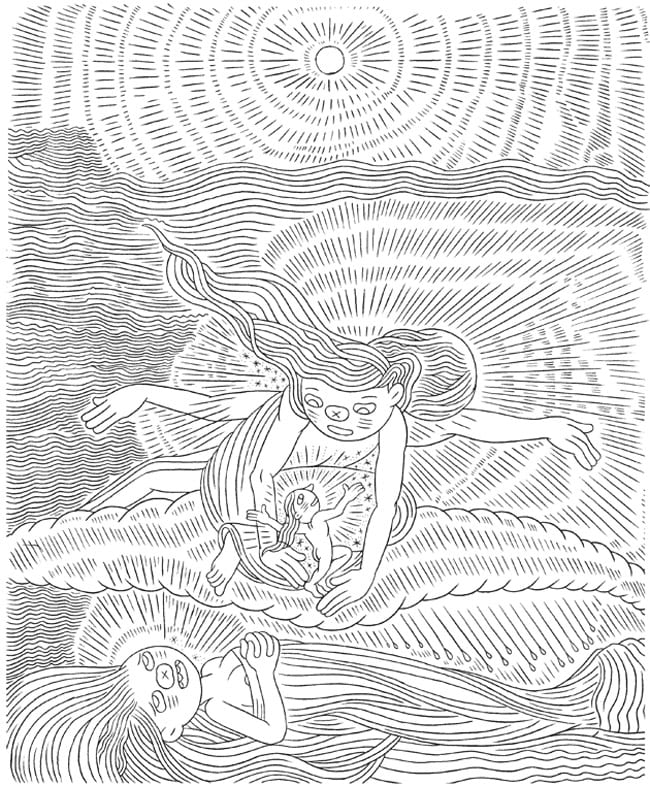

RR: Definitely. I’ve always considered myself a feminist. Whether that’s a loaded term... I definitely see myself as a male artist, but I’ve always related much more to the feminine point of view. Always. In my personal life, and in my work. Against patriarchy, machismo — those kind of aspects [of masculinity]have always been something that I’ve worked against, in my life and in my work, so yeah, I definitely take a feminine — not a female! — point of view. The way that I see myself is also in my chart from what I understand, is about being a bridge between the two. I see myself, and I see my work, especially right now, of being about bringing masculine and feminine together. I feel it within myself, enormously, in the struggles of all aspects of my life, my personal life and everything, as being this... kind of caught in between the two, and wanting to bring it together in my work, by focusing more on the feminine in the balance.

I definitely think about that. I think it comes out in a really interesting way. You can talk about my work being really feminine and appealing to women, and there being sex in here, but I’ve been thinking about it differently. I’ve had this funny idea after doing this, like, I might want to do some erotic artwork. I don’t know how I would go about that. Even though there’s naked ladies in this book, and even though there’s people having sex in this book, I certainly have never made work in the classic sense of comic book or pulp artist making erotic work.

JB: Making work that’s designed to arouse...

RR: Yeah. Or it comes from a completely male view. [in leering voice] Ah, very sexy lady!

JB: Yeah, these seem more... they’re not clinical, they seem more objective, more sweet.

RR: Yeah. It’s like goddess worship. Which I’m definitely into. I even see it as being a balancing thing. Let’s have some more goddess worship to make up for being in a culture that’s 99.9% in the other direction, that doesn’t have any room for it.

JB: You were saying that you already feel like The Cartoon Utopia is going to reach the audience you want it to reach...

JB: You were saying that you already feel like The Cartoon Utopia is going to reach the audience you want it to reach...

RR: I think so. They had advance copies at SPX and APE and they sold out of them both. Then I went to the New York Art Book Fair—I saw people out of the crowd seeing the cover, looking at it, and coming over and picking it up and being like “I WANT THIS,” without even opening it. I think it was people being drawn to it just by the picture on the cover. This is one of those “I AM” images. Like “I am presence”— but it fits with everything in the book. I just copied one of their drawings. It’s from one of the hundreds of groups that I’ve inspired by for the book. Their stuff has imagery that describes this idea of...whatever this stuff is! The etheric body, the cosmic body, the aura: the kind of concepts that all of these groups, all of these belief systems, seem to have in common.

I made the cover look like this so it’d reach more than just comic book people—and at the New York Art Book Fair, I saw it work. There’s this huge crazy mass of stuff shouting for your attention and I was just sitting there, watching people do [a double-take seeing the book’s cover], and I was just like: That’s what I want!