This interview ran in The Comics Journal #256 (October 2003).

Keiji Nakazawa was born in Hiroshima in 1939 and was 6 when the atomic bomb was dropped on his hometown. Only a mile from ground zero, he miraculously survived with minimal injuries, but he lost his father, brother and sister in the ensuing holocaust. Growing up amid the devastation and poverty of postwar Hiroshima, he found solace in the manga of Osamu Tezuka. Inspired by his late father, who had been an artist, he showed his own flair for drawing at an early age. After leaving school to work as a sign painter, he began submitting cartoons to various manga magazines, eventually moving to Tokyo to pursue a full-time career as a cartoonist. In Tokyo, he drew sports and adventure manga for several years until an enlightened editor urged him to write about his own experience as an A-bomb survivor. The result was a 50-page autobiography in comics form, Ore wa Mita (I Saw It), which described the bombing and its aftermath in graphic and heartrending detail. The work inspired Nakazawa’s editor to give him free rein to create the epic graphic novel that would become his life’s work, Hadashi no Gen (Barefoot Gen).

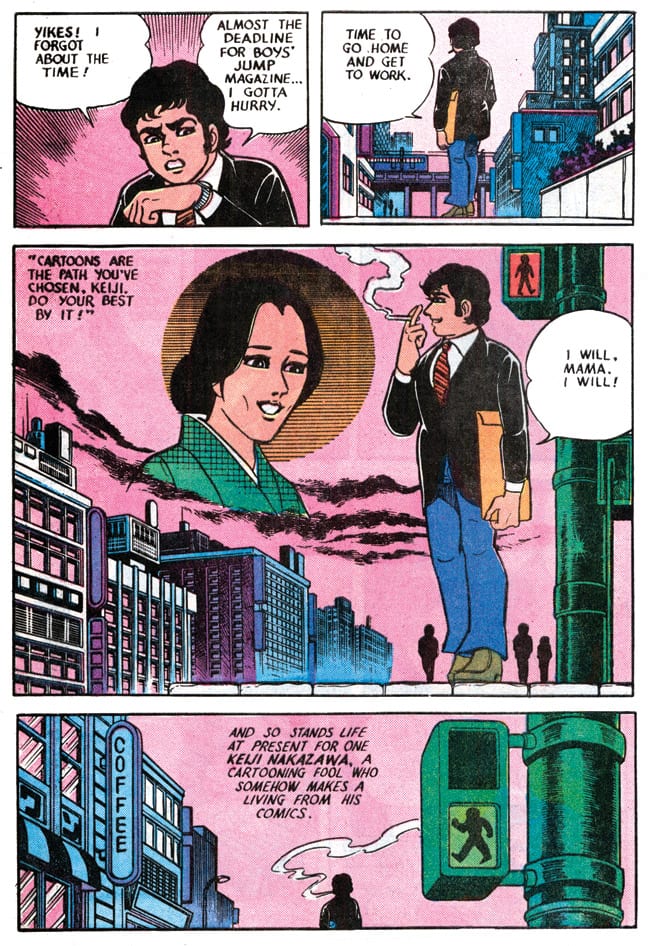

With a young protagonist, Gen Nakaoka, modeled after the author, Gen is an only slightly fictionalized account of Nakazawa’s life in wartime Hiroshima before, during and after the bombing. It was serialized in 1972 and 1973 in the best-selling boys’ comic weekly Shonen Jump, then anthologized in four volumes, becoming a hit with young readers, parents and teachers alike. Gen eventually filled 10 volumes, chronicling the postwar world in which Nakazawa grew up until the death of his mother from leukemia in 1966.

In 1976, a group of young Japanese peace activists walked across the United States as part of that year’s Transcontinental Walk for Peace and Social Justice. They were frequently asked about the Hiroshima bombing, and one of them happened to have a copy of Hadashi no Gen in his backpack. The Americans on the walk were astonished that someone had written a comic about nuclear holocaust, and urged their Japanese friends to translate it into English. Upon returning to Japan, several of the activists formed Project Gen, a non-profit, volunteer group, to do just that.

I encountered Project Gen quite by accident in 1977. I had just arrived in Tokyo to study Japanese music when I met some hippies living in a communal household near my apartment. They urged me to drop by and help out on some sort of translation project they were engaged in. I showed up one day to find a room full of young Japanese and Americans feverishly inking English lettering into blanked-out text balloons on photo-enlarged pages of Gen’s first volume. I only had to read a little of the story to be convinced that this was a project worth volunteering for, and I have been involved in the translation and publication of the Gen series ever since.

I have also gotten to know Keiji Nakazawa well over the years. (I even taught English to his daughter when she was in high school.) He is a feisty, stubborn and warm-hearted man who seems remarkably untraumatized by the unspeakable experiences of his childhood. Most striking is the passion with which he speaks of the need for people everywhere to recognize the horror and injustice of war. Yet you can also sense his rage, calmly articulated but undiluted by the passage of time, against those who perpetrate such horrors on innocent civilians.

Now retired from cartooning, Nakazawa lives with his wife in the suburbs of Tokyo, but he still spends much of the year in his hometown. His most recent project was a live-action film that he wrote and directed about young people growing up in postwar Hiroshima. He is currently working on another film scenario.

Project Gen eventually translated four volumes of Barefoot Gen into English, one or more of which have subsequently been published in French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Swedish, Norwegian, Russian, Korean, Indonesian, Tagalog and Esperanto. A translation of the entire t10-volume series is currently in progress. Gen has also been made into a three-part live-action film, a feature-length animation film, an opera and a musical that was staged in New York City to critical acclaim. — Alan Gleason

[This interview was conducted in two sessions: one conducted in person on Jan. 11, 2003, with a follow-up conversation held via telephone on March 28. The interview was transcribed and translated by Mr. Gleason, who copy-edited it with Milo George. All images from Barefoot Gen and ©Keiji Nakazawa unless otherwise noted. Thanks to Alan Gleason for his permission to post.]

ALAN GLEASON: Among manga translated into English, Barefoot Gen stands out for several reasons. Not only is it the first book-length manga translated into English (in 1978), but it attracted the attention of readers and critics outside of comics because of its serious theme. Readers are aware that Gen is primarily autobiographical, based on your own experiences growing up in wartime and postwar Hiroshima and your direct experience with the atomic bomb. Can you tell us about your childhood before the bomb?

KEIJI NAKAZAWA: I was born in Hiroshima in 1939, less than a mile from the epicenter of the bomb. I was the fourth of five kids. In my earliest memories, we were already in the middle of the war. We didn’t have enough food; I remember we were always hungry, always scrounging for food.

GLEASON: So your earliest memory is of wartime?

NAKAZAWA: It was toward the end of the war. We were just hungry, air raids every day, hiding in the shelter. That was our everyday life.

GLEASON: Did that seem normal to you?

NAKAZAWA: As a kid, you just figure it’s normal. I don’t remember feeling afraid. I didn’t know any different life.

GLEASON: Even during the war, were you and your friends typical kids, wanting to play and have fun?

NAKAZAWA: We were just normal kids. We played games based on the war, Japan vs. The Enemy. That was pretty much all we did all day!

GLEASON: What was your father doing during the war?

NAKAZAWA: He was an artist, and a real eccentric. When he was young, he’d gone to Kyoto and studied lacquer work and Nihonga [traditional Japanese painting using natural pigments]. He was also in an underground theater troupe, with the actors Osamu Takizawa and Eitaro Ozawa. They did a lot of contemporary drama.

During the war, if you were caught with subversive works like that, you could be arrested. Well, they were engaged in an anti-war movement of sorts, and the whole troupe was arrested by the thought police. They took my father away and put him in jail for a year and a half. When I asked where he’d gone, my mother lied and said he’d been drafted into the Army. They held him in the Hiroshima Prefectural Prison. Apparently, they tortured him.

GLEASON: As a child, did you have any feelings about the police, the government, the military?

NAKAZAWA: My father was always saying the war was wrong, that Japan would lose for sure and that maybe then, and only then, the country would get better. He’s the one who shaped my views about the war.

GLEASON: Did that get you in trouble at school or with other kids? Did you notice his views differed from other people’s?

NAKAZAWA: I was just a first-grader; I couldn’t really judge, but I realized my father thought differently about the war than just about anyone else. As I wrote in Gen, word got around at school that he was against the war. But I think I felt kind of proud of that.

GLEASON: Where did your father acquire his anti-war viewpoint?

NAKAZAWA: From his friends and colleagues, I suppose. When he was in Kyoto, a lot of his friends were leftists who were opposed to the war. My mother was terribly worried when she heard him criticize the Emperor. My father would say that the imperial system was dangerous and had led to the creation of the military establishment that was pushing the war. He’d say “Down with the imperial system!”

GLEASON: And that worried your mother?

NAKAZAWA: Oh yes. My mother tried hard to keep his views from being known in the neighborhood. I didn’t really understand how radical his opinions were till after the war.

GLEASON: So you didn’t understand his point of view until you’d grown a bit older.

NAKAZAWA: Yeah, I would think, “So that’s what my father was talking about!” At the time, I didn’t really understand it.

GLEASON: So as you were growing up in postwar Hiroshima, had you already embraced your father’s views on the war?

NAKAZAWA: No, I was still just a kid. I wasn’t capable of thinking about things that deeply. But I would think, “This must all be the Emperor’s fault, like my father said. It’s the fault of the imperial system that we don’t have enough to eat and have to scrounge for food every day.” I learned that from him early on.

Now, I had an uncle, my mother’s brother, Miyake Yoshio, who was a submarine officer in the Navy. He participated in the attack on Pearl Harbor. After the war, he came to our house and said to me “Your father was right.” He told me how he had been ready to go to war and die for the Emperor. Just before he shipped out for Pearl Harbor, he came to see my father. They talked, thinking it was the last time they’d see each other. But just as the attack was to begin, his submarine hit something on the sea bottom and was disabled. They finally got clear, but by the time they surfaced, the attack was over. So he survived. After the war, he came to see us and told us what my father had said to him before he left for Pearl Harbor. “You think Japan can win this war? That’s absurd. We’ll lose for sure. Just come back alive. Don’t kill yourself for nothing. Down with the imperial system!”

When he heard that, my uncle said his heart nearly stopped. But Japan did lose, exactly as my father had predicted. That’s what my uncle meant by my father being right. That was how I was raised by my father, up until Aug. 6, 1945.

8:15 a.m., August 6, 1945

GLEASON: Tell me what happened that day.

NAKAZAWA: Even though it was August, we weren’t on summer vacation. Kids were required to attend classes all summer, the idea being it would turn us into “strong citizens.” I was on my way to the Kanzaki primary school. If I’d gone through the school gate a moment earlier, I wouldn’t be here. Just a little thing like that — I’ve often thought about it. Luck or fate is a strange thing.

As I was about to enter the gate, the mother of a classmate of mine called out to me. She asked whether they were holding our class at the school that day, or at a nearby temple as they sometimes did. They were always switching locations because some schools had been bombed in the air raids. I told her I didn’t know; she’d have to ask the teacher. I was standing right in front of the gate, and the lady was standing about a meter in front of me. Just then we saw a single plane fly overhead. “That’s a B-29!” I said. “Yes, so it is,” she answered. But there was no air-raid siren, like there usually was. The lady said that was really strange. Then, just at that moment, there was a huge flash. It seemed to rush at me. I remember the center was pure white, with blue-white around it and orange-red around that. I saw that flash for an instant, and after that I don’t remember anything.

The next thing I remember, it was pitch dark. It seemed like night. But a moment ago, there had been blue sky overhead. I felt something jabbed in my cheek, a nail — I still have the scar, see? I wondered what had happened. When I tried to get up I found I was under a pile of tiles and boards. The wall of the school had collapsed behind me. I crawled out from under it. In front of me, I saw the lady I’d just been talking to, but now she was lying out in the street. Her hair was all burned, her face and skin were black, and she was staring straight at me.

I went out into the street. It was a wide avenue with a streetcar track running down the middle. On both sides all the houses were collapsed, and the streetcar wires overhead were all twisted around like spider webs. I guess a homing instinct kicked in then. I wasn’t thinking anything except that I had to get home. I ran down the street. As I ran, the first people I met were five or six women walking along in only their underpants. They had all this glass sticking straight out of them, but on different sides — some on their left side, some in front, some on the right, some only on their backs. They’d been struck by glass from shattered windows. Then I saw people who looked like their bodies were colored blue. When you got closer, you realized they were completely covered with glass shards. Farther along I came to a place where people were lying along the roadside, like a human carpet. Their skin was burned completely black. Other people were crawling across the road to drink from a water pump on the other side. I kept going. I just couldn’t understand what had happened. What was really strange was that nobody cried out. Some were silently drinking water as fast as they could; others were sitting there picking the glass out of their bodies. I just kept running along the street till I got to my neighborhood, but it was on fire and I couldn’t get any closer to my house. That was when I first came to my senses, I think. I ran back out to the main street and started crying at the top of my lungs, “Mama! Papa!” running up and down the road looking for them.

There were throngs of people walking silently along, like a parade of ghosts. Their skin was all in strips. The heat from the A-bomb reaches around 5,000 or 6,000 degrees, you know; it melts the skin right off you in an instant. But human skin is pretty amazing stuff. It strips right off you all the way down to your fingernails, and just hangs there. So people were walking along with their hands out in front of them, the skin from their arms dragging on the ground. Just like a bunch of ghosts. When the blast from the bomb hit people in the face, their eyeballs would pop out and dangle from their sockets. So people were staggering along supporting their eyeballs in their hands. If the blast hit you in the belly, it would split you open, so some people had their intestines spilling out and were trying to stuff them back in. Another thing I noticed was that people wearing white clothing had those clothes on intact. But the rest of them was completely burned. Later I learned that the heat of the blast behaved like light hitting a mirror. It reflected off white clothes but was absorbed by dark clothes. Unfortunately, most people at this point in the war were in the habit of wearing dark clothes so they wouldn’t be visible to enemy planes at night.

So I was running through this scene, calling out for my mother and father. Miraculously, a neighbor lady recognized me. She was standing there, covered with glass, pressing her body to try to stop the bleeding. She told me my mother was by the streetcar tracks near a certain intersection. I didn’t think; I just ran. When I got to the intersection, I found my mother sitting on a futon she’d laid out by the side of the street. She was just sitting there staring blankly. I remember we just kept looking at each other; we didn’t have the energy to talk. Then I noticed she was holding something in her arms. It was a baby. The shock of the bombing had hastened the birth.

GLEASON: So she’d given birth right there, by the side of the road?

NAKAZAWA: Yes, just a little while before I got there. It was a girl. We just sat there staring at the ghost parade as it streamed by. People were fleeing the epicenter. We were a little ways outside of town. There were vegetable fields on both sides of the road around us, completely covered with bodies. People would collapse on top of the vegetables. It felt cool to their burned bodies, I guess.

At some point black rain started to fall on us. It had the consistency of heavy oil. No one knew what it was. Somebody said the Americans must be dropping oil on Hiroshima to make the fire spread. But we were very lucky. If we’d fled west, we would have been exposed to the full brunt of the black rain and would have died from the radioactivity. But we’d gone south, and only a few drops fell on us. To the west, so many people died of acute radiation sickness or later of leukemia. So we spent the rest of the day just sitting there. Then, at night, people all around us started moaning for water. We couldn’t sleep. My mother took pity on them and went to the pump to get water for them. They’d grab the bucket, drink the water down as fast as they could, and then, in a matter of seconds, they’d fall over — dead. Maybe it was a shock to their system or maybe they’d been hanging on for dear life, just craving water, so when they finally got some, they could let go and die.

When the next day dawned, just about everyone lying in the fields was dead. The stink of dead bodies was horrible. You couldn’t breathe, especially when the midsummer sun heated up. We decided to climb a nearby hill, Sarayama, where the trees would provide shade. But the hill was so covered with people, we couldn’t find any room to sit, so we gave up and went down again. Right about then I noticed that the back of my head and neck felt really itchy. It turned out I’d suffered burns from the bomb there. The school wall hadn’t completely blocked the flash and it had burned me on the head and neck. There was a first-aid station the Army had set up in a tent at the bottom of the hill, so we went there to get treatment for me. But they didn’t have any medicine at all. They told my mother to put juice from a squash plant on my wounds. She did that for a year and they healed.

There was nowhere to go, but we needed to let my older brother Yasuto know we were alive, so we went back to the main street near where our house had been and waited for him to return. My brother had been drafted to work at the Kure Shipyard outside Hiroshima — he helped build the battleship Yamato — so he wasn’t in Hiroshima when the bomb fell. Eventually he did find us, and then the four of us — with the baby — went out to a town outside of Hiroshima called Eba, where we had relatives. They weren’t happy to see us because they were already short on food.

GLEASON: You describe that situation in Barefoot Gen. Was it just like in the book?

NAKAZAWA: Yes, exactly the way I wrote about it in Gen. They let us stay in a storeroom they had, but they were really nasty to us.

GLEASON: When did you learn that the rest of your family had died in the fire?

NAKAZAWA: Not right away. After we arrived in Eba and settled down a little, my mother told me for the first time how they had died, just as I described it in Gen. They were trapped under the fallen beams of our house and burned to death there. My little brother Susumu’s head had been caught in the collapsed doorway, but he could still move his legs. My mother tried to pull him out, but she couldn’t. He was crying and crying how much it hurt, and my father was yelling for my mother to do something. But there was nothing she could do. She temporarily lost her mind. They were dying right in front of her. She decided she’d die with them, but just as the flames reached our house, a neighbor came by and dragged her away. He told her there was no point in her dying too. She could still hear the cries of my brother and father from inside the flames as she was pulled away. My sister Eiko had died instantly, thank goodness.

After a few days, I went back with Yasuto to where the house had been, and we found the bones of my father, sister and little brother right there where they had died. We put their skulls in a bucket and took them back with us. I still remember, when I held my little brother’s skull in my hands, the cold chill I felt through my whole body, even on a hot summer day. I was thinking how terrible it must have been for him, crying out for my mother, his head caught under that beam, his body burning. That was the first time I saw Hiroshima since we’d left for Eba. All that was left of the city was a vast scorched plain. The only structures still standing were concrete cisterns that had held water for firefighting purposes. These tanks were full of corpses, people who’d tried to escape the fires. You could see parents and children clinging to each other. They looked so human, even in death. As you got closer to the epicenter, the cisterns were overflowing with bodies. People had jumped into the tank, one after the other, falling on top of each other. It was very symmetrical, the way the corpses were piled up. The only things moving over the ruins were flies. There were clouds of flies everywhere. They’d swarm after you. I thought they were going to eat me alive. Downtown, below the bridge at the epicenter of the bombing, the river was filled with bloated, rotting corpses. They’d wash up and downstream with the tide. Every so often you’d hear a loud pop when the gas inside a corpse built up and its belly burst open. The whole city was filled with bodies. Everywhere I walked, there were charred, blackened corpses.

GLEASON: So you stayed in Eba for some time after the bombing?

NAKAZAWA: Yes, but we were treated so badly by people there — they clearly didn’t want us around — that we decided to leave as soon as we could. We started collecting lumber and when we had enough, we built a shack on the rubble back in town, not far from where the Atomic Dome still stands.

They reopened a school in Hiroshima within a month after the end of the war. But we had nothing to study with — no paper, no textbooks, no desks. We spent our free time climbing around in the ruins, like on the Atomic Dome. You could see all the way across what was left of Hiroshima from up there. Around that time, they had cremation fires burning nonstop. There were acres and acres of bones piled up from the cremations, everywhere you looked.

GLEASON: Did you have friends you hung out with, like Gen’s best friend Ryuta?

NAKAZAWA: Well, I was the worst behaved kid in my school. I was always getting in fights. I was the boss of my own little gang. We’d scavenge around through the ruins, picking up scrap metal to sell on the black market for pocket money. The black market was the only place you could get most necessities, and of course it was run by the Yakuza. You couldn’t avoid them. That was just the way it was then. Everyone was desperate.

Comics

GLEASON: When did you first discover comics, or start drawing?

NAKAZAWA: I think it was when I was in third grade, around 1948, when I first saw the comic book Shin-Takarajima [New Treasure Island] by Osamu Tezuka. The first I heard of it was when one of my classmates got a hold of it. I kept bugging him to let me borrow it, but he wouldn’t let me. I wanted it so badly. So I saved up my money from selling scrap metal and finally bought my own copy. I spent all my free time reading it over and over.

GLEASON: Had you heard of Tezuka before that?

NAKAZAWA: No, never.

GLEASON: Why did you want to see the comic so badly?

NAKAZAWA: We had no other means of entertainment then. Comics were new and exciting. Also, there had never been big, thick, book-size comic magazines like Shin-Takarajima before, only much shorter comics. The sheer size of it was thrilling to me.

GLEASON: So it was like the big manga weeklies we see nowadays, like Shonen Jump?

NAKAZAWA: Yeah, around 250 pages. Tezuka’s was the first manga I remember seeing, and that’s what I grew up on.

GLEASON: Were you already drawing before you first saw Tezuka’s work?

NAKAZAWA: I’d always been good at drawing, even as a little kid, thanks to my father’s example. I did well at art in school. Once I got hold of the manga, I started trying to copy Tezuka’s images. I became more and more of a manga fanatic as time went by. In fifth or sixth grade, I sent in a cartoon I’d drawn on a postcard for a contest run by a Tokyo publisher. I got an honorable mention and my name appeared in their magazine. I was overjoyed!

GLEASON: Did your classmates think you were weird for being a tough guy who also drew cartoons?

NAKAZAWA: Oh, it made me popular. Kids would line up at school and ask me to draw cartoons for them — I was that good! I think it was in my blood, something I inherited from my father. I loved pictures. I could draw for hours on end, completely in my own world. And if you keep doing something you love, you’re bound to get better at it.

When I entered middle school, I became even more obsessed with manga. By then I’d set my heart on being a professional cartoonist when I grew up. I wanted to go on to high school, but my family couldn’t afford to pay my tuition. So when I graduated from middle school, I was only 15 but I had to find a job. I wanted to do something that would help with my cartooning, so I decided to be a sign painter. Painting signs gives you practice sketching, lettering and coloring — all skills that you need for manga. So I painted signs all day, and when I got home, I’d draw manga. I did that until I was 22. I kept sending my manga work to publishers in Tokyo, won a number of prizes and gradually acquired more and more confidence in my work.

GLEASON: What sort of work were you doing?

NAKAZAWA: Period pieces — historical adventures, samurai dramas. Usually in 16-page installments.

GLEASON: How did your mother react to your desire to become a professional cartoonist?

NAKAZAWA: She was really against it. She knew what it was like to be married to an artist, how poor you’re going to be! She didn’t want me following in his footsteps. I’d get mad at her and tell her I was going to draw no matter what she said. I drew every day — I was a manga maniac!

GLEASON: So Tezuka was your biggest influence. Who are some other manga artists you liked?

NAKAZAWA: Eiichi Fukui, Noboru Baba, Jiro Ota — I really liked them. They all appeared in the manga magazines of the time. All of them — and Tezuka is the prime example — had something to say. They had a point of view and, you might say, a sense of justice. You could tell there was a philosophical outlook underlying their work. This had a big influence on me.

GLEASON: In the ’60s, some new genres of manga appeared — the hardboiled dramatic narratives known as gekiga, and the more avant-garde work by the angura or “underground” artists. What did you think of them?

NAKAZAWA: I just thought they were fads. I wasn’t sure they could even be called manga. The angura writers in particular just seemed self-indulgent. They made no effort to convey their point of view — if they had one — to the reader. Their attitude seemed to be, “If you don’t get it, that’s your problem.”

GLEASON: Yoshiharu Tsuge is often mentioned as one of the prime avant-garde manga artists. What do you think of his work?

NAKAZAWA: Some of it I understand, but a lot of it I don’t! I know a lot of people describe his work as art. Personally, I don’t see anything particularly artistic about it.

GLEASON: Do you have any favorite cartoons or cartoonists from the U.S. or other countries?

NAKAZAWA: When I was young, I really liked the Walt Disney comics, and Blondie. And I read a lot of 10-cent comics — Westerns and adventure stories — which I think were the inspiration for the Japanese gekiga genre. I thought American comics were second to none when it came to the quality of the drawing, but I wasn’t so impressed by the storylines. I don’t like the American approach you see in comics like Superman, where different people write the stories and draw the pictures. To me, that’s not real cartooning. A true cartoonist does both the story and the pictures himself. That’s what makes it a complete, integrated work. I don’t think the division of labor approach used in America lends itself to the best cartooning.

Some Japanese cartoonists have started imitating the U.S. approach, Takao Saito [creator of the long-running gekiga series Golgo 13], for example. He writes the scenario and farms out the drawing, and I don’t think the result is all that good.

GLEASON: In recent years, there have been more comics with a point of view, as you mentioned; comics that address social issues, as Barefoot Gen did. One famous example is Art Spiegelman’s Maus. Tezuka’s Adolf series also attracted some attention in the U.S. when it was translated. What do you think of works like these?

NAKAZAWA: I view them as orthodox works in the best sense of the word, because they express a point of view about the world. As I said before, I think the best cartoonists all do that. That’s why I admire Tezuka so much. Nowadays, though, writers use whatever it takes — sex, violence — to sell as many copies as they can. I have no interest in reading the stuff being churned out today.

Full-time Manga

NAKAZAWA: When I was 22, I couldn’t stand it anymore. I decided I had to draw manga full-time, so I moved to Tokyo. It was 1961. I found a tiny three-mat room in the Yanaka district, and started carrying my manuscripts around to different publishers.

GLEASON: Did you have letters of introduction or anything?

NAKAZAWA: Nothing. I’d just walk in and ask them to look at my stuff. Mostly they’d just say, “Looks interesting, come by again when you have some more.” Finally, I made my debut in the monthly manga magazine Shonen Gaho [Boys’ Pictorial]. It happened pretty fast, actually — I’d only been in Tokyo a year when I got the job. The title was Spark One. It combined auto racing and spy intrigue.

GLEASON: What was the connection between auto racing and espionage?

NAKAZAWA: One racing team was trying to steal the secrets of another team’s car design. That ran in Shonen Gaho for a year. I got another job doing a short sci-fi series called Uchu Jirafu [Space Giraffe] for the manga weekly Shonen King.

When those series ended, I started working as an assistant for Naoki Tsuji, who was a very popular cartoonist. During that time I also was doing short pieces for magazines like Kodansha’s Bokura [We], Shonen Sunday and Shonen magazine. I did all kinds of genres — sci-fi, baseball, samurais — I liked drawing them all, so I’d try my hand at anything.

GLEASON: Were you being commissioned by the magazines to draw specific types of stories?

NAKAZAWA: No, I’d draw what I wanted and peddle it around.

Then, in 1966, my mother died. I got a telegram and rushed back to Hiroshima, but it was too late; she was already lying in a coffin. I was so grateful to her. If it hadn’t been for my mother, who knows what would have happened to me. I would’ve been a war orphan — I’d either be dead or in jail, most likely. I went to the crematorium to collect her ashes. Actually, when you’re cremated, there are always some bones left — the skull, backbone, arm and leg bones. But there were no bones left in my mother’s ashes. Nothing. It was an incredible shock to me. I think the radiation must have invaded her bones and weakened them to the point that they just disintegrated at the end. I was appalled.

Since coming to Tokyo, I hadn’t said a word about being an A-bomb survivor to anyone. People in Tokyo looked at you very strangely if you talked about it, so I learned to keep quiet. There was still an irrational fear among many Japanese that you could “catch” radiation sickness from A-bomb victims. There were plenty of people like that, even in a big city like Tokyo.

I was enraged that the bomb had taken even my mother’s bones. All the way on the train back to Tokyo, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I realized I’d never thought seriously about the bomb, the war and why it happened. The more I thought about it, the more obvious it was that the Japanese had not confronted these issues at all. They hadn’t accepted their own responsibility for the war. I decided from then on, I’d write about the bomb and the war, and pin the blame where it belonged. Within a week after getting back to Tokyo, I wrote my first work about the bomb, Kuroi Ame ni Utarete [Struck by Black Rain]. It’s about young people in postwar Hiroshima getting involved in the black market for weapons. The main character is an A-bomb survivor whose hatred drives him to kill an American black marketeer. He asks the Americans, “Who are you to talk about justice when you massacred hundreds of thousands of innocent people in Hiroshima, in Nagasaki, in the firebombing of Tokyo? Was that what you call justice?”

The editors who read Struck by Black Rain were very moved by it and told me to write more. I wound up writing five books in my “Black” series — Black River, Black Silence and so on. Black Rain was published in serial form in Manga Punch, an “adult” manga magazine by a small publisher, Hobunsha. The big publishers turned it down. They said it was too radical for them, too political.

GLEASON: What was it they objected to, specifically?

NAKAZAWA: They said they were afraid they’d get harassed by the CIA or sued by the U.S. government for writing about the A-bomb. When I mentioned this to my editor at Hobunsha, he laughed and said, “Hey, they can arrest me! That would be great publicity!”

But “adult” — meaning erotic — magazines like Manga Punch had a very small share of the market. I wanted to write on these themes for a bigger publisher. I was lucky to find a very good editor at one such publisher, Shueisha. His name was Tadasu Nagano. He really championed my work. He urged me to write more about the A-bomb, so I began my “Peace” series, starting with Aru Hi Totsuzen ni [One Day, Suddenly].

GLEASON: So by the late ’60s, you were writing manga primarily on themes like the war and the A-bomb. Did you write about your own Hiroshima experience in those works?

NAKAZAWA: Oh yes, I based a lot of what I wrote on my own experiences. But it didn’t really occur to me to write about what happened to me personally until the magazine Monthly Shonen Jump started running a series of “cartoonist autobiographies.” They asked me to write one about myself. At first, I didn’t want to, but they kept after me. The result was Ore wa Mita [I Saw It]. When Nagano read it, he told me, “You should do a longer series based on this. You can make it as many pages as you want and we can run it for as long as you want.” I could hardly believe it. That was the first time an editor had ever said anything like that to me. I was incredibly grateful, and felt I should do the best job I could. That was how Hadashi no Gen [Barefoot Gen] came about.

If it hadn’t been for Nagano, Gen never would have happened. But after a year and a half, he was kicked upstairs and made director of his division, and another editor took his place at Jump. The new editor had different tastes, and decided to cancel Gen. After that, the monthly magazine Shimin [Citizen] picked it up for a year. They went out of business, so next Gen moved to another monthly, Bunka Hyoron [Cultural Criticism], where it appeared for three and a half years. Then that magazine ran out of money, so Gen moved to Kyoiku Hyoron [Educational Criticism] for another three and a half years.

GLEASON: What pace was Gen being serialized at in these publications?

NAKAZAWA: Sixteen pages, every month. That took Gen up to its present ending, 10 volumes’ worth.

GLEASON: Someone once told me he thought that Jump had cancelled Gen due to right-wing pressure. Is there any truth to that?

NAKAZAWA: No, none whatsoever; it was just the whim of the new editor. We expected right-wing pressure, but we never experienced any. When Gen first appeared, I warned my wife to be prepared to get hate mail or threatening phone calls. Not a thing. Gen only got praise. Even the right-wingers cried when they read it!

GLEASON: You’ve also mentioned before that the Japanese left wanted to use Gen for their own political agenda, and that at one point the Japan Communist Party pestered you to join them.

NAKAZAWA: Oh yeah, sure, but I just said no. They left me alone after that. Actually, you could say the Communists turned me down too; Bunka Hyoron was affiliated with the Communist Party, but they cancelled Gen when they ran out of money.

GLEASON: So for several years, you were kept busy with Gen. But you were writing other works, too, during that time, right?

NAKAZAWA: Oh yes, quite a few. I wrote for Monthly Champion and Manga Action. Mostly social commentary, but lighter stuff too. I did a manga called Yakyu Baka [Baseball Fool], about a kid who really was a complete fool for baseball. You get tired of doing serious stuff all the time! But I was also doing work in the same vein as Gen and Okinawa. I did a serial called Geki no Kawa [Geki’s River] about a boy growing up in Manchuria when it was a Japanese colony.

GLEASON: At some point, you also started giving talks in public. When was that?

NAKAZAWA: I guess after Gen first appeared as a four-volume set, so that would be in the mid-’70s.

GLEASON: You were speaking about your experiences as an A-bomb survivor?

NAKAZAWA: Yes, and about peace issues. To citizens’ groups, schools, teachers’ groups around Japan.

GLEASON: Are you still doing that?

NAKAZAWA: Not now. I’m tired. I was still doing it last year, but I don’t want to anymore. At the peak, I was giving 20, 25 talks a year.

GLEASON: What would people ask you about?

NAKAZAWA: They wanted to know what the war and the atomic bombing were really like. It was the first time people had heard the truth. That’s what they told me everywhere I went.

GLEASON: I’ve heard that Japanese school history books don’t say much of anything about the bomb. Why not?

NAKAZAWA: The government probably doesn’t want to risk encouraging anti-American sentiment. But the facts are the facts. People should be told what happened.

GLEASON: Americans, too, generally know about the two A-bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but hardly anyone knows about the extent of the B-29 air raids that leveled most Japanese cities before that. In Tokyo alone, 100,000 people were killed in one night of firebombing — that’s nearly as many as died in Hiroshima. And though most Americans know about the A-bombs, a common knee-jerk reaction to any discussion of their effects is “What about Pearl Harbor?” — that sort of thing. Even Americans who consider themselves liberals tend to have very mixed emotions about the A-bombs — whether they were necessary to end the war or not. Yet those who read Gen often say it is more even-handed than they expected in spreading the blame for the war. You don’t just blame America for dropping the bomb; you blame the Japanese militarists for starting the war, and the imperial system for allowing the militarists to wield such power in the first place. You definitely don’t come across as anti-American. Is that how you always viewed the war, even when you were young?

NAKAZAWA: Well, I spent a lot of time thinking about why it happened. And if you think it through, the answer clearly lies with the militarists and the imperial system. And as a young kid, of course, I’d heard my father criticizing them too.

GLEASON: As you were growing up in postwar Hiroshima, did you talk about things like that with your friends?

NAKAZAWA: Never! Everyone had their hands full trying to survive. I kept my thoughts to myself. If I tried to bring it up, no one wanted to hear about it.

GLEASON: When did you start talking about it?

NAKAZAWA: Pretty recently, I guess. It’s only lately that I’ve really started speaking out about how bad the entire imperial system is. For a while I only expressed those views in writing, through my manga starting in the ’60s.

GLEASON: But I gather that, even if you didn’t talk directly with your colleagues about your experiences, you could tell that people like your editor Nagano shared your views.

NAKAZAWA: I was really very lucky to have an editor like him. Without Nagano, I never would have been able to draw the “Peace” series. And he knew it, too. He’d say to me, “There are 40 editors here at Jump and I’m the only one who understands what you’re doing!”

GLEASON: Would you talk to Nagano about your views on the emperor?

NAKAZAWA: Not really, but he knew how I felt from my manga. And he never censored a single word of what I wrote.

GLEASON: Was there ever pressure from his higher-ups at the company about your work?

NAKAZAWA: Oh yeah. One series I did, Okinawa, was going to be published in book form by Shueisha. But the top brass pressured them to cancel it.

GLEASON: Was that before the U.S. had returned Okinawa to Japan [in 1972]?

NAKAZAWA: Before.

GLEASON: Do you think the cancellation was for the same reason you gave that Japanese textbooks don’t talk about the A-bombs — to avoid provoking anti-American sentiment?

NAKAZAWA: Certainly. That wasn’t my purpose in writing it, but they assumed I was criticizing the U.S. occupation of Okinawa. The top management at Shueisha was very nervous about such things.

GLEASON: Don’t you find it odd that they’d allow you to write about the A-bomb, but not about Okinawa?

NAKAZAWA: I guess they thought the Okinawa theme was more controversial because the situation was still “delicate” — it wasn’t resolved yet at the time.

GLEASON: Did you have any other run-ins of that sort?

NAKAZAWA: That was about the extent of it. The problem is that I got labeled as a lefty cartoonist. That’s still how I’m viewed by the media.

GLEASON: When did they first start labeling you as that?

NAKAZAWA: Ever since Gen, I guess. There simply weren’t too many other cartoonists taking on controversial issues like the war and the political system.

GLEASON: Are there any other cartoonists writing on such topics whose work you admire?

NAKAZAWA: Hmmm… Sanpei Shirato is about it. He wrote the Kamui Den [Legend of Kamui] series.

GLEASON: Recently there have been some examples of right-wing political manga, like the Gomanism [Philosophy of Arrogance] series by Yoshinori Kobayashi. Kobayashi made headlines recently when he defended Japan’s colonization of Taiwan, didn’t he?

NAKAZAWA: Right. What can I say? All I know is, if you live through something like the A-bomb, you know that war is too horrible not to be avoided at all costs, regardless of the justifications offered for it.

GLEASON: As we speak, the U.S. government is pressing for a war with Iraq. The polls suggest that many Americans support a war if they think it can be pursued from a distance, through bombs and missiles, so that American soldiers don’t get killed. What strikes me about the debate on the war, particularly among U.S. politicians, is that few express concern that even if hardly any Americans die, thousands of Iraqis probably will.

NAKAZAWA: I think it’s simply that Americans haven’t experienced massive bombings first-hand. All their wars in the past century were fought overseas. Vietnam is a good example.

GLEASON: The terrorist attacks on September 11 are often described as a turning point because they are the first attack on American soil to cause thousands of civilian deaths since the Civil War. Now the government seems to be calculating that it can do what it wants in Iraq as long as too many Americans don’t die.

NAKAZAWA: Japan is just as bad. Here’s a country that experienced complete devastation in the last war, and yet ultra-nationalists are crawling out of the woodwork again, glorifying the war and trying to rewrite the history textbooks. And as usual they talk about restoring the emperor to his rightful position of absolute authority.

GLEASON: Do you think there’s really a possibility of that happening?

NAKAZAWA: Definitely. That’s why I say we need to dismantle the whole imperial system.

(Non) Fiction

GLEASON: Let me ask you some more questions about your experiences growing up in postwar Japan, which provided the background for Barefoot Gen: You’ve said that Gen is mostly autobiographical, and the main character Gen Nakaoka is clearly modeled after yourself. How did you go about combining autobiography with fiction in developing your story?

NAKAZAWA: I definitely based it on my own experiences growing up. I was writing Gen in the late ’60s, so I looked back at what I was doing each year through the ’50s and ’60s, and what Japanese society was like at each point.

GLEASON: Some sequences seem like they might be straight autobiography, like when Gen’s family goes to live with the unsympathetic relatives in Eba right after the bombing. You mentioned earlier that this is lifted directly from your own experience. But, for example, you have a subplot in volume two about how Gen and Ryuta get work caring for Seiji, a young artist who has lost the use of his hands in the bombing, and how they inspire him to begin painting again, holding the brush in his teeth. Some of Gen’s adventures, like that one, are so dramatic I have to ask — did that really happen to you? And if not, where did you get the idea from?

NAKAZAWA: It didn’t happen to me, but it was a combination of true stories I heard and things that happened in my neighborhood. For example, there really was a young A-bomb victim who taught herself to paint with her teeth. And Seiji’s household, which is treated like a pariah by the neighbors, is modeled after a house we kids called the haunted house because a badly injured victim lived there. I wanted to tell the story of the artist to show how people can overcome the greatest adversity. If you can’t use your hands, use your teeth. As I wrote at the beginning of Gen, the real theme of the story is symbolized by wheat, which springs back no matter how many times it’s trampled.

GLEASON: One of the most significant characters in the first four volumes of Gen is Gen’s baby sister. Much of the story revolves around her birth, illness and premature death. I know from what you said earlier that this is based on what happened to your own little sister.

NAKAZAWA: Yes, she died after only a few months, most likely of malnutrition, and we cremated her by the ocean, just as Gen’s sister Tomoko was in the story.

GLEASON: At the end of the 10th volume, Gen’s mother dies. Did you intend all along to bring the story up to that point and end it there?

NAKAZAWA: Yes. Although I don’t really view the Gen series as complete, I wanted to tell Gen’s story up to that point at least. So far, that’s where I’ve left it.

GLEASON: Do you intend to resume it at some point?

NAKAZAWA: No, not really.

GLEASON: So the story itself is unfinished, but you don’t plan to add to it?

NAKAZAWA: That’s right. There’s so much more that could be told of Gen’s story, but now I feel that Gen can best live on in the imagination of the reader.

GLEASON: In later volumes of Gen, you write about kids in Hiroshima trying to survive in an underground economy — the black market, and what seems like the dominance of the Yakuza gangs in early postwar society. I assume that’s also based on what you saw growing up. How did you feel about that environment when you were growing up in it?

NAKAZAWA: So many kids in Hiroshima were war orphans, and if you were an orphan, your only means of survival was to join the Yakuza. That was just the way it was. Hiroshima was burned flat; it was a clean slate — it offered unlimited opportunities for the Yakuza. They moved in right away and engaged in furious turf wars. And the war orphans made perfect recruits — they had no relatives who would care if they died, and they wanted someone to look after them. If my mother hadn’t been there to take care of me, I would have joined the Yakuza too. There’s no question about it.

GLEASON: Did you have friends who did follow that path, like Gen’s sidekick Ryuta?

NAKAZAWA: Yes, Ryuta was based on a friend of mine. He was always in and out of jail. But he’s alive and well — and still a Yakuza.

Gen Abroad

GLEASON: How did the movement to translate Gen into other languages begin?

NAKAZAWA: While it was still being serialized, a Japanese college student named Masahiro Oshima came to visit me and said he and his friends wanted to translate Gen into English. I said it was fine with me and to go ahead and translate as much of it as they could. Oshima put a group of volunteers together and called it Project Gen. I think it wasn’t too long afterward that you came on board.

GLEASON: Right. I met Oshima and his group in 1977 when I’d just moved to Tokyo. They were still working on the first volume and they put me to work proofreading the pages they’d already translated and lettered.

NAKAZAWA: I have to admit, I was a little disappointed in that first English volume. The paper was cheap, and the lettering was all over the place.

GLEASON: Yeah, our letterers were amateurs who didn’t really read and write English that well. It was pretty messy. We didn’t know how to deal with the fact that Japanese comics read from right to left, either. Nowadays everything is automatically flipped in advance, but back then we were trying to stay true to the original. We cut out each frame and pasted them back in reverse order, and re-drew the speech balloons only if the sequence inside a frame needed to be reversed. We didn’t realize it at the time, but it was the first full-length manga to be published in English. We didn’t have any models to go on.

NAKAZAWA: I didn’t know that.

GLEASON: There was a lot of trial and error. By the fourth volume, I think it looked a bit better. We flipped all the pages at the outset, as most English manga publishers do now, and one of America’s best professional letterers [Tom Orzechowski] did the lettering for us. You gave that approach your blessing, but I wondered — how do you feel about seeing your work appear backwards, a mirror image of the original?

NAKAZAWA: I don’t mind. As long as the story gets told, it doesn’t really matter to me.

GLEASON: So you don’t mind when your characters all turn into southpaws?

NAKAZAWA: Nah.

GLEASON: There’s now a new group of volunteers called Project Gen based here in Japan that has recently been working on a new set of translations in various languages. How did that get started?

NAKAZAWA: It was just like with your group; I got a call from someone saying they wanted to work on Gen, and I said, go ahead. They already produced Korean and Russian editions, which have been published — all 10 volumes. Now they’re working on a new English version of all 10 volumes, an Indonesian version and a Thai version.

Filmmaking and Surviving

GLEASON: Gen has also been turned into several films over the years, including a three-part live-action series and a two-part full-length anime. Then, about three years ago, you produced and directed another live-action film about Hiroshima.

NAKAZAWA: Right. It was called Okonomi Hatchan [literally Young Hatchi the Okonomi Maker — “okonomi” is a Hiroshima specialty, a meal-sized, meat-and-vegetable-filled hotcake]. It’s about a young guy struggling to make a go of his okonomi business, and the different customers who come to his shop. One of them is a second-generation A-bomb victim, who gets in a fight with someone from Tokyo who makes light of the bomb. The story takes place in the present. That was my first experience at directing a film myself.

GLEASON: I know you were concerned about the possible effects of your exposure to radiation on your own children. You’ve told me that you were very worried before your daughter Keiko was born, and how relieved you were when she turned out completely healthy. How about yourself? Do you have any lingering aftereffects from the bomb?

NAKAZAWA: I’ve had diabetes for 30 years. That’s one of the designated A-bomb related diseases, one that many survivors get. In the past couple of years, I’ve had serious problems with my eyesight, but I don’t know if that’s a direct effect or not.

GLEASON: Do you associate with any organizations of A-bomb survivors?

NAKAZAWA: No, I don’t see any point in it. I say what I want to say about the bomb through my manga. I don’t feel the need to join a group to draw more attention to what we went through. I don’t join cartoonist associations either! I’m really a lone-wolf type.

GLEASON: I want to ask about your approach to cartooning. In Japan, it’s been traditional for manga artists —particularly successful ones — to set up a studio and hire assistants to do a lot of the work. What has been your approach over the years?

NAKAZAWA: I’ve always done everything myself. I start with the story, then I do the drawing. For years, my wife has been my only assistant. She draws the frame lines, erases the penciling, puts in the screen-tone, cleans it up. I do everything else. I generally don’t like depending on someone else. My wife’s the only one I trust.

GLEASON: When you first started out as a cartoonist in Tokyo, you worked as an apprentice. Do you think the assistant system is good for someone who wants to learn the craft?

NAKAZAWA: Yes, it’s a very good way to learn. It forces you to improve in the areas where you’re weak.

GLEASON: Didn’t you have young cartoonists asking if they could work as your assistant? Did you turn them down?

NAKAZAWA: Yes, I got asked. I did hire an assistant for four years at one point, but I didn’t like taking the time to teach him. It interfered with my work, so I decided I was better off working alone.

GLEASON: Then you’re very fortunate to have such a talented wife, I’d say.

NAKAZAWA: Oh, I agree! At first, she couldn’t do anything, but she was a quick study. Eventually, she was able to work so fast it was like having 12 assistants!

Summing Up, Looking Forward

GLEASON: Are you working on any new projects now?

NAKAZAWA: I’d like to make another film, and that would be about it. It would be about the children of divorced parents. Couples seem to get divorced at the drop of a hat these days. What happens to their kids? I’ve been writing a manga on this subject, Jizo no Matsu, about children of broken homes. Matsu is a young boy whose mother divorces his father and takes another lover. Matsu cries for his mom but she won’t come back. I’d like to make that into a movie. I’ve already finished the manga version, and I’m working on the film scenario. I would like to direct it myself, too. But movies cost a lot of money, so I don’t know.

GLEASON: You seem to be increasingly interested in film as a medium of expression. How does it compare with manga for you?

NAKAZAWA: Sometimes, drawing manga, you can become frustrated with the limitations. For example, you might want to show a dramatic action, or a flow of movement, that you simply can’t express in a series of frames on a page. Another thing you can have in film is real speech, the sound of the character’s voice. And you can add music and sound effects. You can’t do those things with manga!

GLEASON: Do you find film so satisfying that you would put manga aside in favor of making movies?

NAKAZAWA: Yes, at this point I’d be happy just making movies.

GLEASON: Are you still drawing manga?

NAKAZAWA: No, I don’t draw anymore. I’m too tired.

GLEASON: It’s been over 30 years since you started drawing Barefoot Gen. How do you feel about Gen as a body of work now?

NAKAZAWA: Well, it was basically my autobiography, so I always felt as if I were recounting the first half of my life, creating a story out of the process by which I survived and grew up.

GLEASON: Looking back, do you have anything you would have done differently with the story?

NAKAZAWA: No, I feel pretty satisfied with how it turned out.

GLEASON: Gen has been translated and published in several languages. What do you think of the response it has received overseas?

NAKAZAWA: What struck me most was how poorly informed people outside Japan were about the atomic bomb and nuclear war. I’d like to think that reading Gen has helped people get a sense of the horror of the war and the bombing, as well as the danger of depriving people of their freedom of speech.

GLEASON: Are you satisfied with the exposure Gen’s story has received overseas?

NAKAZAWA: No, I’m very dissatisfied. I think the story needs to be told and heard far more widely than it has so far.

GLEASON: How do you think cartoonists should respond to the problems we face in the world today?

NAKAZAWA: No other medium compares to manga in its sheer mass appeal. So all artists — cartoonists especially — should be active at times like this. If an artist is angry at what is going on in the world, he should be writing about it.