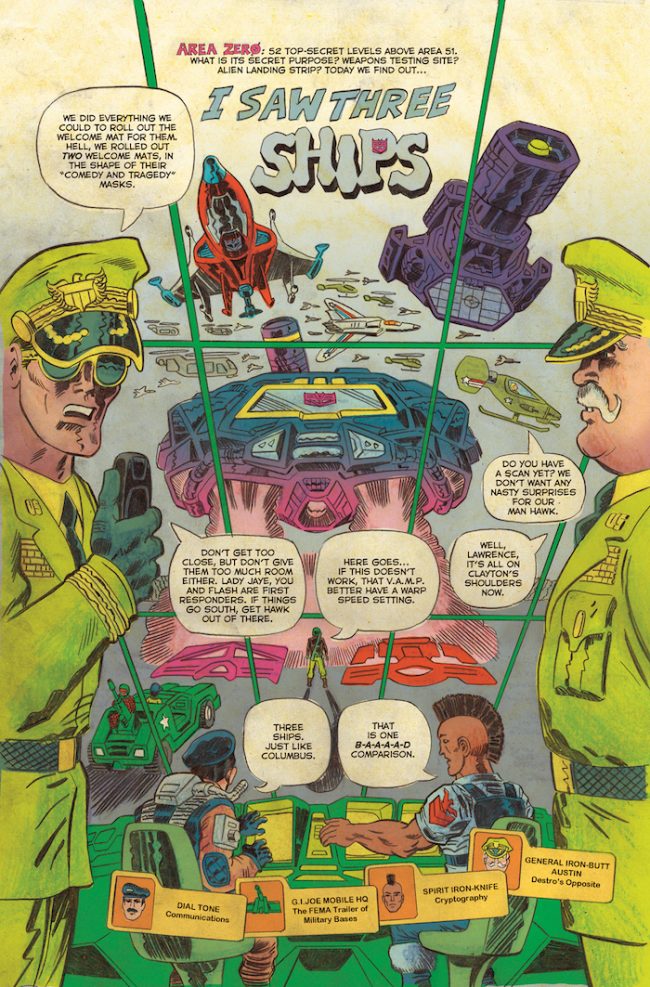

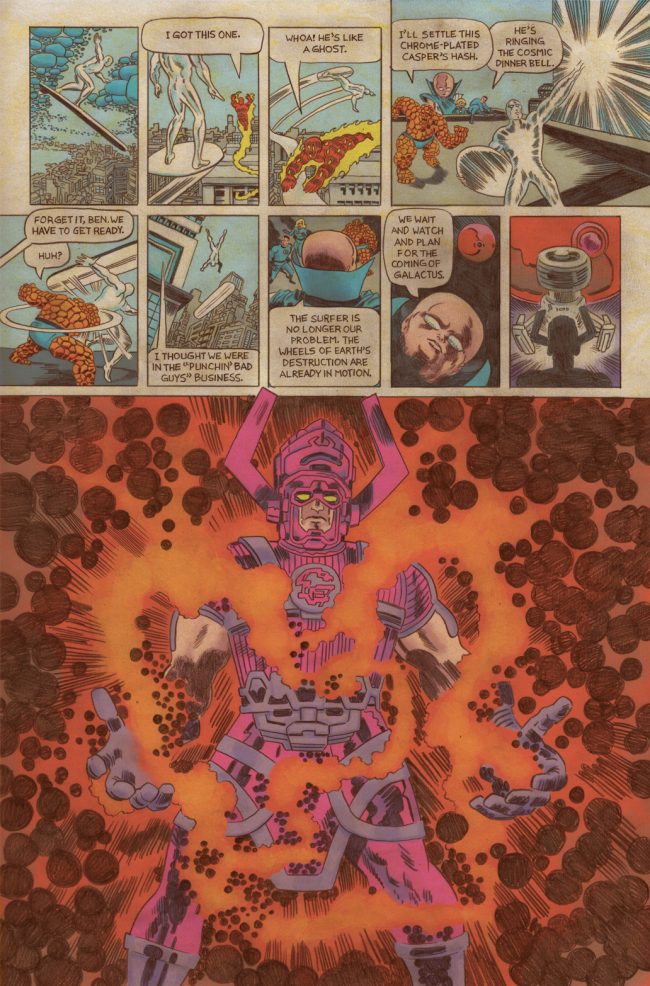

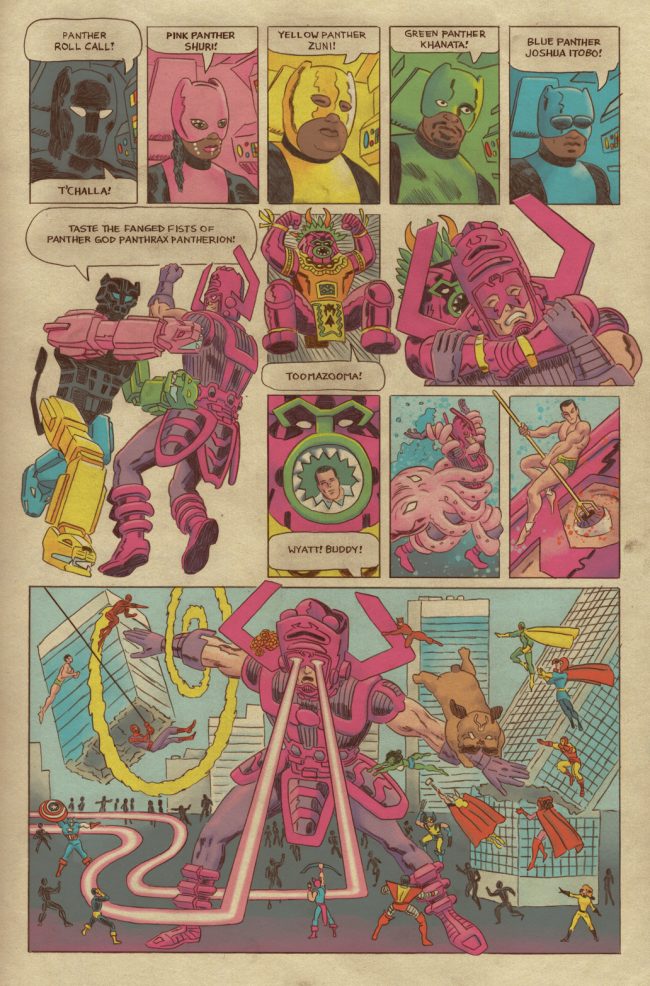

Tom Scioli’s career in comics began in 1999, when he was awarded the Xeric grant for The Myth of 8-Opus. 8-Opus garnered a mixed reception to Scioli’s art aesthetic, a studied imitation of Jack Kirby. Following a series of releases featuring the titular 8-Opus character, Scioli collaborated with writer Joe Casey on Gødland from 2005 to 2012. Another Kirby-inspired superhero title, Godland updated the formula with a contemporary sensibility. Following Godland, Scioli moved into a more stylistically experimental period with American Barbarian. Fueled by a desire to produce more freely and reflexively, American Barbarian was serialized online before its initial publication by Adhouse Books. Beginning in 2014, Scioli’s breakout work, Transformers vs. G.I. Joe, was published by IDW. Co-written by John Barber, it was a bold reimagining and amalgamation of the source material. Marked by Scioli’s experimentation with layout and structure, Transformers vs G.I. Joe revealed the scope of his vision when unfettered by constraints. In 2016, Super Powers, written and drawn by Scioli, debuted as a three page back up feature in Cave Carson has a Cybernetic Eye. Based on DC's 1980s Super Powers property, Scioli’s strip utilized little-used characters like the Wonder Twins alongside mainstays like Batgirl in service to a disjointed, psychedelic, meandering narrative aimed at the essences of the characters. In 2018, Scioli revisited giant robots with Go-Bots. Published by IDW, Go-Bots was less thoroughly researched than its predecessor, Transformers vs. G.I. Joe. It was also more somber, more minimal, and more succinct in its storytelling. In 2019, Scioli delivered Fantastic Four: Grand Design, an encapsulation and exploration of the early years of the Fantastic Four. He is about to release a print edition of Kirby, a biographical strip based on the life of Jack Kirby which first appeared online. While Scioli’s early reputation as a Kirby imitator was formed on the basis of his art style, that reputation remains apt on the basis of his approach and his trajectory, both of which increasingly stress imagination and stylistic experimentation over all else. That he has been able to put his distinctive mark on a body of work that is so heavily comprised of licensed properties is a testament to the strength of his vision. Over the course of several interviews in 2019, Tom Scioli and Ian Thomas discussed Scioli’s career to date.

Tom Scioli’s career in comics began in 1999, when he was awarded the Xeric grant for The Myth of 8-Opus. 8-Opus garnered a mixed reception to Scioli’s art aesthetic, a studied imitation of Jack Kirby. Following a series of releases featuring the titular 8-Opus character, Scioli collaborated with writer Joe Casey on Gødland from 2005 to 2012. Another Kirby-inspired superhero title, Godland updated the formula with a contemporary sensibility. Following Godland, Scioli moved into a more stylistically experimental period with American Barbarian. Fueled by a desire to produce more freely and reflexively, American Barbarian was serialized online before its initial publication by Adhouse Books. Beginning in 2014, Scioli’s breakout work, Transformers vs. G.I. Joe, was published by IDW. Co-written by John Barber, it was a bold reimagining and amalgamation of the source material. Marked by Scioli’s experimentation with layout and structure, Transformers vs G.I. Joe revealed the scope of his vision when unfettered by constraints. In 2016, Super Powers, written and drawn by Scioli, debuted as a three page back up feature in Cave Carson has a Cybernetic Eye. Based on DC's 1980s Super Powers property, Scioli’s strip utilized little-used characters like the Wonder Twins alongside mainstays like Batgirl in service to a disjointed, psychedelic, meandering narrative aimed at the essences of the characters. In 2018, Scioli revisited giant robots with Go-Bots. Published by IDW, Go-Bots was less thoroughly researched than its predecessor, Transformers vs. G.I. Joe. It was also more somber, more minimal, and more succinct in its storytelling. In 2019, Scioli delivered Fantastic Four: Grand Design, an encapsulation and exploration of the early years of the Fantastic Four. He is about to release a print edition of Kirby, a biographical strip based on the life of Jack Kirby which first appeared online. While Scioli’s early reputation as a Kirby imitator was formed on the basis of his art style, that reputation remains apt on the basis of his approach and his trajectory, both of which increasingly stress imagination and stylistic experimentation over all else. That he has been able to put his distinctive mark on a body of work that is so heavily comprised of licensed properties is a testament to the strength of his vision. Over the course of several interviews in 2019, Tom Scioli and Ian Thomas discussed Scioli’s career to date.

IAN THOMAS: I see you talking insightfully about film stuff when you appear on Cartoonist Kayfabe. It makes me think that you approach comics in cinematic terms. Does film figure a lot into your creative process or your creative history?

TOM SCIOLI: Yeah, I mean, I’m a student of film. I took film classes in school and I was an aspiring filmmaker. In college, I took film production classes and things. A lot of the learning I did there I apply to comics, like the writing end of things and then even like, you know, the similarity between like storyboards and comics, it comes from like a study of screenwriting and that kind of visualization.

Did you go to school to study film?

Like, among other things. I went to Pitt and I majored in Art, but I took a lot of film classes through Pittsburgh Filmmakers.

And you are originally from Philadelphia, is that right?

That’s right, yeah.

Did you move to Pittsburgh for school?

I moved here for school, yeah.

Can you talk at all about your relationship with music and what kind of what kind of music you tend to listen to, if you listen to much music?

Yeah, the type of music I like if I had to narrow it down would be like psychedelic rock, or just psychedelic music, period. So, the Beatles, the Who, the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix. And then more recent would stuff would be like MGMT, the Lemon Twigs, King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard, you know?

So, Psychedelic leaning into Prog a little bit, would that be fair?

Yeah. I'm a really big fan of rock operas, concept albums, music that tells a story, where the songs add up to something greater than the sum of their parts, that’s the sweet spot for me.

And as far as non-comics related reading, are you mostly reading nonfiction? Fiction?

For the past maybe five years, or so, it’s been nonfiction stuff, like oral histories and things like that; like there was that book about the history of comedy, I’m trying to think of the name of the author.

Is that the Kliph Nesteroff book?

Kliph Nesteroff, that’s it. So, his book. And there was a book about In Living Color, a couple years back. Books about the late-night wars. Stuff like that. Most of the fiction reading I do is comics.

And what are your comic reading habits?

I have my favorites that I get at the comic book store, but then I just do a ton of reading of stuff from the library, then I’m just getting out of my comfort zone, just kind of trying everything.

You have one of these very distinctive perspectives, where I see other things across the gamut of pop culture and I wonder ‘What would Tom Scioli think of this?’ in an effort to pinpoint or contextualize your perspective. I'm re-watching like Neon Genesis Evangelion, for example, or Mandy, Panos Cosmatos’s recent movie starring Nic Cage.

That Nic Cage thing I haven’t checked out, but Evangelion, I’ve tried reading Evangelion and I've gotten through parts of it and haven’t been able to finish it. Same with the show. I’ve watched it here and there, I’m into it, I like it. Some of these long running manga, it’s a question of how much you want to commit to it and I’m just not finding myself in the mood, but it’s something I’ve attempted a bunch of times over the years. I definitely took a few close looks at Evangelion when I was first doing Transformers vs. G.I. Joe just trying to get my head around that genre of giant robots, just trying to approach it from as many directions as possible.

Can you talk about your earliest experience of comics and how you became immersed in that world? From reading them to writing them, how did that go?

So, comics started in childhood, they were just one of those things that were just kind of around, part of the landscape of childhood when I was growing up. My dad wasn’t a comic collector. I had an older brother that was somewhat into comics, but not really. But, like Ed Piskor and Jim Rugg had comics around the house, where, for me, it was like you’d go to 7-11 or the bookstore at the mall and maybe I'd check them out or look through them and maybe spend some of like the little bit of pocket money that you have getting one. It wasn’t something that I had a ton of access to. I guess some of the earliest stuff would have been like like the comic books that came with He-Man figures. There were probably things earlier than that, too. He-Man’s like ’81. I probably had some stuff like a Marvel Comics Star Wars digest. I think that was one that I had pretty early. When I was a kid it was like anything Star Wars. It was like a way to take Star Wars home with you. VCR’s weren’t really common at that point.

Had you been collecting comics for a while by the time you were going to school in Pittsburgh?

When I was little it was like a comic here and there and it would be like a Star Wars comic or a Superman comic. When I got a little older, around ten, eleven, twelve, something like that, I started more actively collecting comics. It was around ’87, so comics [were] a little more in the forefront, you had just had that year of Dark Knight Returns and all that stuff, but I wasn't keyed into any of that stuff. It was just like here's a bunch of cool looking [stuff], like Spider-Man had a black costume that looked super cool and I guess maybe prior to that there was Secret Wars, which was like a toy where you could finally have some cool toys of the various super heroes, mainly that I knew from cartoons on TV and stuff, so the Secret Wars comic was kind of another gateway.

And then that kind of ebbed and flowed for me and then somebody brought like Frank Miller’s Batman: Year One, so then I learned about this other more serious vein of comics that excited me. Then comic book stores really started popping up, so I found my way into a comic book store and it was like here’s some cool stuff, like Batman: the Killing Joke. And then I was curious about old comics, like the Jack Kirby stuff. I didn’t know the name Jack Kirby, but it's like ‘Oh, here's like some cool old looking issue of Captain America. It’s only three dollars. I can afford three dollars for this thing that seems like a priceless object.’

And without really knowing what that was, it captivated you on an emotional level and from there you kind of explored it?

Yeah, exactly, and kind of got deeper. And then I kind of got out of comics as I went through high school. My interest waned the way it normally does for kids as they get older and move into adolescence, but then when I went to college in Pittsburgh, Phantom of the Attic was nearby and I’d be sort of checking things out and that was like a further education into comics. And then I got really into it at that point.

What clicked? Being able to immerse yourself in it more?

Yes, just more access to it. I was older and more mobile and more self-sufficient and then having a really good comic book store in walking distance, where they’re inviting and friendly and helpful. Then keying into, like, Jack Kirby and Nexus and Frank Miller and then going deep with that stuff.

This would be the mid 90’s to early aughts. You're talking Nexus, so that's Steve Rude and Mike Baron. Were you into Madman?

Yeah, it's exactly that era. And then Hellboy comes around that time. There was just a lot of exciting stuff.

Was there a big leap between that time when you were getting pumped about these exciting comics and when you decided to make them yourself?

No, it was kind of around that time, or maybe a year or two after that. So around that time I was like ‘Okay, yeah, I want to do comics.’ As far as career goes, it was one option. My main thing was getting into animation or gallery art.

It was all art-related, though?

Yeah, I wanted to do something art related, storytelling-related, and something primarily visual. So all those things were kind of competing, but, with the comics thing, it took me a really long time to attempt to actually, start to finish, make a comic, which is, looking back, kind of crazy. But then I talked to other people who were sort of like aspiring comics creators and it does seem like it is like a real roadblock.

My advice is just to make a comic and do it soon as you can. I had all these fears and all these thoughts in my head that like you’ve got do all these things to prepare. Also, around that time I was reading Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics and the way he laid out how comics function seemed to me so complicated and had so many factors that you have to balance that like how do you even begin? And, of course, he created that as a way of analyzing comics and not as a how-to for making comics, but I was treating it as a how-to for making comics, so I was thinking ‘I need to practice. I need to study before I put pen to paper and make that comic.' There was a lot of postponement of what I should have done a lot sooner.

I do think that McCloud book is a great explainer, but, like you said, it does make it seem very complex, but that was the only game in town for many years.

Yeah, and again, he did make that how to make comics later on, but understanding comics wasn’t that. I think it's similar to when you first see Pointillism and all these millions of little dots add up to this picture and it’s so perfectly balanced. And you’re like ‘How did that person do that?’ And you imagine them sort of measuring out where to put each dot and choosing the exact perfect color. Then when you learn about how they actually did it, it’s like no, you just kind of do it and you get into a zone and things start to form, but you're looking at this finished product, rather than seeing somebody go through the process.

Prior to the publication of The Myth of 8-Opus, how long had you been reading or immersing yourself in comics before you started to make them?

It was like two years of college, studying art and studying comics really hard. Then I did my first couple comics. A year after that I started doing the 8-Opus stuff.

What form did those earliest efforts take? Were you, even back then, working within the parameters of Jack Kirby emulation that you had on display in 8-Opus?

Yeah, the first comics I did were Kirby emulation. They were a little further from the mark because I was learning. I wanted to draw like Kirby, but I didn’t start off that way. I worked my way towards it.

Was that a choice that you made because you felt that it would help you learn the craft? Was it based solely on your admiration of Kirby and his work?

It was admiration. I was just really drawn to his work. It was just so strange and so different. And it was different from the natural way that I drew. I just thought it would be an interesting project. How would I do that? Could I learn to draw like Kirby? And if I could, wouldn’t that be so cool?

You set about achieving that by studying the material and emulating it as closely as possible? What were the big stretches you had to make to acclimate yourself to that style of art?

One of the things early on was the thing of unlearning what you learned and forgetting what you know because there’s a lot of things that Kirby does that go counter to academic drawing or go counter to natural ways of depicting things. The prettying up that you internalize when you’re somebody who draws or makes art, to forget some of that stuff and deliberately make jarring overlaps and juxtapositions.

I remember learning how to crop, where there’d be a panel where a half a person’s face would be cut off, and wondering how to do that, how to decide where to crop it, and wondering if I had to draw the rest of the figure. It was just breaking it down. Like with groupings, the way he would group things, there was a math to it.

A ‘math,’ did you say?

A math, M-A-T-H. If a character is fighting a group of opponents, it’s usually an odd number, three, five, seven. Making theories, like ‘I think this is how he does this, let me try it out.’ What I ended up having was almost like a caricature of the way Jack Kirby worked that I internalized, not realizing that it was a caricature.

I think in a lot of ways I sold it short. His stuff isn’t as simple as I dismissed it as being. There is a lot of beauty and draftsmanship, it’s just a matter of where you look. If you’re looking at his more out there stuff—if you’re looking at Captain Victory or his late-seventies stuff, that’s one thing, but if you’re looking at stuff he did in the forties and fifties, it’s a whole other thing altogether.

It sounds me like you were trying to distill it.

Distill it, yeah. Amplify it. Intensify it.

Was 8-Opus created for the purpose of applying for the Xeric Grant?

Was 8-Opus created for the purpose of applying for the Xeric Grant?

No, I just created it. I was making superhero characters and that was just the latest one and that was the next thing I was going to work on, so it was just timed with when I was applying for the Xeric. If I had applied six months earlier, it would have been a different project.

After you received the Xeric, did you find that lines of communication were opened to you? What changed?

Yeah. I had something that other artists could check out and communicate with me about. I ended up talking to Erik Larsen and Dave Sim and people who were in that end of things.

After it was completed and you got your first proper comic book printed, what was your promotion strategy? To whom did you decide to send promotions?

I had a list of retailers that I’d gotten at a comic convention, so I sent ashcans out to retailers. I took out ads in the Comics Buyer’s Guide, also. They were teaser ads where each ad was like a chapter of a little story.

Did Jack Kirby Collector play a role in your reception?

They were into it. John Morrow, he was way into it, very receptive and very supportive. I was like a kid when I did it, too, so I think there was a little bit of ‘Hey, the kid’s got talent,’ that sort of thing. I encountered a lot of support in that way, people pulling for the plucky kid.

Did you sense any kind of generational disconnect between what you were trying to do and your reasons for trying to do it and the audience who accepted or were even drawn to it?

Thinking back, the people who were into it, were into it, but there were also people who weren’t. Some people got the whole Kirby thing and some people were just like ‘Wait a second, why are you imitating Kirby?’ or ‘Kirby was good and all, but his day is done, what’s this have to do with 1999?’ or ‘Kirby is great. I love him. Why are you ripping him off?’ It was a variety of reactions that fell into those categories.

It seemed to be drawing a lot from Kirby’s Fourth World. Your execution of it was very rigid, in terms of layout and inking and figure work. In these early efforts, were you just drawing on everything that you were jazzed about at that point?

It seemed to be drawing a lot from Kirby’s Fourth World. Your execution of it was very rigid, in terms of layout and inking and figure work. In these early efforts, were you just drawing on everything that you were jazzed about at that point?

Yeah, I was into Joseph Campbell, the Hindu pantheon, and all these other things that were relatively new to me.

When did Joseph Campbell hit your brain in terms of your practice of making art? It seems to me in the plots and trajectories of your early stuff that Kirby and Campbell go hand in hand for you?

Sure, yeah, they do. It seems like Kirby’s work never crossed Joseph Campbell’s path, but I feel like if it had, it would have resonated. But I don’t think one was aware of the other.

As far as your personal artistic education, were you into Campbell before Kirby?

I was into Campbell before Kirby. I discovered Campbell in high school. That’s when Bill Moyers was doing interviews with him that would play on TV. That’s where I was exposed to him. I was aware of Kirby in a vague way for a really long time, but I was more clearly aware of Campbell. I learned about Campbell in high school and I learned about Kirby in college.

Do you think the application of Campbell’s theories is better suited to someone who is just starting out or do you find them to be universal to any point in the life a creator?

I’ve gone back and forth. If you’re just lost in the woods and want to tell a story, Joseph Campbell is really helpful that way. If you have a story and it’s not quite finding a shape - it still feels like a series of incidents and set pieces and moments - Campbell can help you find the way and sift through it, especially if you’re telling heroic stories. Sometimes I feel like people cling to it to such a degree that it’s really limiting.

It’s been helpful to me and it’s even been helpful to me very recently. I’d put Campbell aside for a while, then somewhat recently picked him back up and it was helpful with Fantastic Four: Grand Design.

In the subsequent 8-Opus graphic novels, such as The Myth of 8-Opus: The Labyrinth, that rigidness falls away. Was that due to a growing confidence? Feeling like you had wrung everything out of that initial approach and those parameters under which you’d been working?

In a lot of ways, I worked through the Kirby influence. I really, in the beginning, wanted to make something that you could maybe mistake for Kirby and emulating that approach was my focus. As it went on, you kind of find your own voice and I began to let other influences come in and I became more flexible, less rigid, and became more my own artist and less an apprentice.

I still see your work mentioned in the context of that Kirby emulation. It might be less true now, but it seems to me that it’s married to your legacy as an artist. What are your thoughts on that?

I’m fine with it. Once they figure out a shorthand for describing your work that kind of sticks. Your work can change and do all kinds of things but that shorthand sticks. So, I think even if I were to radically reinvent my style at this point, the shorthand would always be ‘Oh, the Kirby guy. That’s the Kirby guy.’

There’s worse things. I’m fine with it. I love Kirby. It’s what I was going for. I’m still a huge fan. I haven’t soured on Kirby’s work, or anything. It’s fine. I don’t mind that comparison, especially since I invited it. Also, I understand that kind of shorthand - when readers or reviewers use that shorthand to describe me - is a marketing tool. It’s a handle. It’s not the art, itself, so I’m okay with that being whatever it’s going to be.

Do you think it has ever cost you opportunities or precluded you from doing projects that you wanted to do?

Do you think it has ever cost you opportunities or precluded you from doing projects that you wanted to do?

Sure, in the beginning definitely. If I had drawn in a more standard style, like a style that was more of that moment, I think breaking into comics would have been easier. Breaking into comics was a very long and very difficult process for me and I think the market was not looking for someone who, in 2000 or 2001, was drawing like Kirby. The market was not looking for that.

What about that approach made you feel so strongly as to not change it up in exchange for accessibility or making yourself more marketable as an artist?

It was just a stubbornness, a vision. Sometimes I have a contrarian nature, like ‘Everyone else is wrong and I’m right and they’ll come around. Maybe the problem isn’t that I’m trying to emulate Kirby, or drawing in this style that isn’t considered marketable. Maybe it’s just that I’m not doing a good enough job of it and if I just double down and do it even better. Maybe I’m just not doing a good enough job of being a Kirby imitator and, if I double down, the next thing will be even better.’ You can spend a lot of years like that.

Gødland started on the basis of Erik Larsen matching you and Joe Casey up. What was your relationship to Erik Larsen at that point and then what was meeting up with Joe Casey like?

My relationship with Erik Larsen was a mentor relationship. He wanted to help me break into comics in a bigger way. He liked my work. He saw potential in it and thought it was worth his time, so that’s what that relationship was. Once he became the publisher at Image, he got in touch with me and got in touch with Joe Casey and kind of paired us off. Just from talking to Joe and knowing me and my situation, he saw that we were both going in similar directions or at least in complementary directions and thought that it would be a smart pairing.

Were you able to find your footing in that collaboration pretty quickly?

Were you able to find your footing in that collaboration pretty quickly?

Yeah, we hit it off really quick and threw a bunch of ideas at each other. We were both really excited about what we were coming up with and we clicked pretty easily. We found a division of labor that made sense.

What was that division of labor?

I would send him some visual ideas or fragmentary story ideas and he would create a page by page plot, like when they talk about Marvel method, the legendary Marvel method. From our conversations, he’d come up with a very clearly broken down plot. Then I’d take that and interpret it, in a way that made sense to me, into a visual thing, then he’d go back in and add dialogue to it.

Were there any impediments in the collaboration? Did you find that any of your ideas were a hard-sell?

More good than bad came out of the collaboration. I think we did accomplish some really cool stuff, but it was frustrating to have an idea and have to sell it and not just put it in there. When you’re doing something by yourself, you don’t have to justify your ideas. Sometimes you have an idea that seems weird, or silly, or stupid, or maybe even seems like a bad idea, but if you really believe in it, you can put it in. When convincing someone else to go along with your crazy idea becomes part of the equation, it can take some of the fun out of it and be demoralizing. And vice versa.

Sometimes he would have an idea that I wasn’t thrilled with, or that we’d have a disagreement about, and I’d go along with it and have to spend hours drawing something I couldn’t get behind. Not that any of these ideas were bad ideas, but it wasn’t necessarily something I would want to say. So, I’d try to be a good collaborator, a good compromiser. I feel like that’s just built into that system. Our collaboration was really good and really healthy and really fruitful, but under the best circumstances there is going to be discomfort and dissatisfaction and unhappiness, from time to time.

Gødland was your first major collaboration, right?

Yes.

In some of our other conversations, it sounded to me like you sort of limped to the finish line on Gødland. Is that a fair description?

In some of our other conversations, it sounded to me like you sort of limped to the finish line on Gødland. Is that a fair description?

Totally, yeah.

To me, that work from later in the series was when you were hitting your stride. Do you think that period toward the end of the run was representative of your winning Joe’s trust, maybe not along the lines of your abilities, but maybe your ideas?

I don’t know if it’s that. The way I feel when I'm making something and the way it comes off or the way it works or doesn't work on a page are totally different things. The best is when I'm feeling really good about something while I'm making it. But sometimes you feel really, really bad about what you're making and then it works. To me, that struggle ended up creating something really cool. Then, sometimes, you feel really good about something and it doesn’t come out right. The fact that some really cool stuff was happening in those final issues isn’t contradicted by the real struggle that I was having internally, while I was doing those things.

Creatively, I was also in a transitional phase, too. While I was working on those last issues, I was also working on American Barbarian. I might have even been working on some of my other webcomics, so you’re seeing my work going from one phase to another, trying out different things. I’m very proud of that work, but those last couple issues were really difficult to do, just because I had put so many years into that project. Being so close to the finish, but not close enough to the finish, was really emotionally painful. When I drew the final page of Gødland and I was done, I looked at the final page and re-drew it because I wasn’t happy with it. In some ways I was ready to be done with it, but in other ways I didn’t want to let go of it. On some level I did enjoy working on it, even eight years in.

In an interview you did with Tom Spurgeon in 2008, you cited flagging sales as the impetus for ending it. Did you find that it was an uphill battle throughout the run of Gødland for what you and Joe were aiming to do with it to be understood?

In an interview you did with Tom Spurgeon in 2008, you cited flagging sales as the impetus for ending it. Did you find that it was an uphill battle throughout the run of Gødland for what you and Joe were aiming to do with it to be understood?

We were talking earlier about how smoothly things went in the beginning. When we were making it we really thought we had a hit on our hands. Before it came out, we both felt really good about what we were producing.

The initial issues did okay. There were other comics that went on to be big successes that started with similar numbers, but we had a really hard time progressing beyond that point. Only speaking for myself, it was a strain on me and my enthusiasm for the project. I wasn’t as seasoned in dealing with the rejection that is part of putting your stuff out there like that. Around issue sixteen, we did an issue that was sixty cents, one of those kinds of gimmicks, and that ended up being disastrous. We printed a thing that wasn’t sold for a lot of money and we kind of dug a hole for ourselves that the book never quite climbed out of. I feel like if Gødland was a hit, we might still be doing it. It was demoralizing. At least, it was for me back then. Not being as seasoned, it felt like a real rejection. To me, it’s a miracle when anything is a success, so I couldn’t tell you what made it not a financial windfall, or whatever, but since then I’ve heard from a lot of creators who do creator-owned stuff at Image with the exact same frustration. They created something that they really believed in and felt was awesome and then saw it crash and burn. I don’t remember hearing a bunch of stories like that back then. That was relatively new.

What was your experience with editorial at Image at that time? Did you and Joe answer to anyone beyond each other?

No. If you have an editor at Image, it’s because you hired an editor. There’s not an internal editorial—at least, there wasn’t then and, as far as I know, there still isn’t, at least for creator-owned projects. [Image] was mainly trying to figure out how to help. There was never an external pressure to change anything, nothing like that.

Do you think Gødland’s reception has changed in the intervening years since the book’s completion?

A lot of people tell me how much they like it. It’s hard to say because even when the book was a current book coming out, I heard from people who were really fond of it. It doesn’t seem like that’s changed at all.

It struck me that the relationships explored in Gødland were almost exclusively familial relationships. Did this exploration of the family dynamic happen organically or was it by design?

From my end, it just grew into that. Maybe Joe had different intentions. The lack of a romantic interest was something that felt like, maybe we should have engineered this thing a little differently to allow for that. When you have a cast that’s entirely familial, you lose the possibility in romantic tension that is maybe a necessary ingredient for a superhero team comic. By not having that, you’re creating something interesting, but are you creating something commercially viable? Maybe you’re losing an essential element.

At the time, I had much purer notions of art and I felt that commercial considerations were beneath what we were trying to accomplish. We were trying to make a greater philosophical point. We wanted it to be financially successful, so maybe we were kidding ourselves a little bit by being too pure or high-minded with our artistic ambitions.

Your treatment of the villains was especially sympathetic.

The villains really were the stars of it. They were the ones who, I feel like, even after we finished the series—if you were going to do a spin-off or a sequel, it should focus on the villains. Because we weren’t constrained by any editorial dictates, we were able to play with the formula and tilt the weight of the formula in different directions.

The villains are always favorites. They’re always really interesting and they get the best lines. We tilted way, way toward the villains. They kind of dominated it, but I feel like so much of that comic was organic and evolved in the same way as when Jack Kirby and Stan Lee were doing Fantastic Four. We just went where the story led us and those characters just stole the show. They were like the Fonz, or whatever, and it just became their show all of a sudden.

Metaphysical and mystical themes run through Gødland and, really, all of your work. Can you speak to what role religion or spirituality has played in your life?

Metaphysical and mystical themes run through Gødland and, really, all of your work. Can you speak to what role religion or spirituality has played in your life?

Biographically, I grew up Catholic and went to Catholic school, so I was sort of steeped in this mysticism. You’d learn about these magical ideas, but they were taught to you like they were common, everyday things. I’ve had my own ups and downs with that, rebelling against this body of knowledge that I grew up in, that was part of family life and school life. But it’s left its mark on my work. Yeah, there’s mysticism and metaphysical themes.

I feel like Satan’s Soldier, for all its very obvious Satanic symbolism, is a very Catholic work. You have to have grown up Catholic and then rejected it to create something like Satan’s Soldier. My dad was holding a copy of Satan’s Soldier and was like ‘Oh, what is this?’ as he was flipping through it. And when I told him ‘Oh, it’s Satan’s Soldier,’ it leapt out of his hand. The idea of holding something that was Satanic in nature frightened him or repulsed him and it flew out of his hand, but I feel like if he had read it in its entirety, he really would have gotten something out of it, like it would’ve warmed his heart, or something. It doesn’t get more personal than that.

What did you take away from Gødland, not only as a creator, but as a collaborator?

As a creator, that was my bootcamp, or that was college. That was where I learned what it’s like to do a real, legit comic book. I learned everything there as a creator.

A lot of it is tied to the idea of collaboration, too. It taught me what aspects of collaboration didn’t work for me and what I need to be willing to do to create my work. I learned that if you want to get your way all the time, you gotta do everything. You can’t collaborate on any aspect of it if you want total, complete, unquestioned control of your work. That was a big one.

I have collaborated since then. I collaborated with John Barber on Transformers vs. G.I. Joe, but I went into it with my experience with Gødland, with the idea that if I was going to collaborate, I had to be the one in charge. It can’t be 50-50 partnership. I have the final say, I’m in charge. We’re working on this thing together, but I have ultimate veto power. That’s how I had to collaborate after Gødland. I don’t know if I still feel that way. I’m not feeling very collaborative at the moment, but I feel like, at this point, if I did collaborate with somebody, I would be a lot more open, but it would have to be very special circumstances for me to agree to collaborate with somebody at this point.

Have you rejected a lot of opportunities or invitations to collaborate since Gødland?

Ummmm, yeah. Yeah [chuckles]. It’s a lot easier to get a comic made if you’re willing to be part of a team. It’s very easy to make a comic by yourself because you just sit down and do it, but that’s sort of rarefied air to have a company hand you that - especially the properties I’ve worked on - them to trust one person with all that. It’s a little tricky to get someone to sign off on that.

Can you place American Barbarian into the context of your body of work? When did it appear and when did you make it?

Can you place American Barbarian into the context of your body of work? When did it appear and when did you make it?

I was working on it while I was still working on Gødland. It was towards the end of Gødland.

And before it was published, American Barbarian was serialized online, correct?

Yeah, it was a webcomic first.

What were your intentions for American Barbarian? I felt like you were bringing to bear a lot of stuff that you started 8-Opus.

I think a big part of it was that, up to that point, I had been working on a lot of sprawling series that were multiple volumes, just the sort of endless run-on sentence that comics were for most of the history of comics, things without an end, where they just keep going and going.

I had invested several years into Myth of 8-Opus and I had invested several years into Gødland and they were still going and I didn’t feel like I was close to concluding either of them when I started envisioning American Barbarian, so I really wanted to make something discrete, that had a beginning, middle, and end and that could be one volume. Like ‘Here it is, here’s American Barbarian,’ and not ‘Here’s American Barbarian volume one and you may have to wait three years for volume two and it still might not be done with the story.’

So, I wanted to do something that was complete and I didn't want to start drawing until I had the whole story figured out start to finish because that was another frustration that I had had, working on something and not being a hundred percent sure where it was going. It made me anxious and it made me kind of lose faith in what I was working on from time to time. It hurt my morale to be working on something that took eight years, ten years, and not be sure of every step of it.

When you're working, even if it's in a longer form, you like to at least have a resolution envisioned. Is that fair to say?

Yeah, and at that point, after having Myth of 8-Opus and Gødland, which were pretty loosely plotted and didn't have any kind of solid idea of exactly where they were going, I wanted to get every beat nailed down. So, that was American Barbarian and I worked on the story for a really long time and then it finally all gelled into a complete story that I could graph every moment of and I saw it unfold like I was watching a movie. The whole thing came to me. I was working on it by bit and slogging along and then suddenly I could sort of see the whole thing. And so that night I stayed up as late as I had to stay up to just write down every single thing so I wouldn't forget it the next morning and then that was the roadmap that I had for it.

Was it coming out regularly once you started to put it online?

Was it coming out regularly once you started to put it online?

I think it was pretty regular, once I had it online. I came up with the whole story, then I did the first, like, issue, the first chapter, and the idea was to put it out as a regular comic, like Gødland, but with a definite end, where it would come out as issues and then be collected in one volume. So, I was sort of pitching that first issue around and I wasn't really having any luck. I couldn’t find a company, like an Image or a Dark Horse or a Top Shelf to put it out like a regular comic. So then I just did it as a web comic and that was my first web comic.

What do you think didn't catch with those publishers to whom you pitched it?

It had changed a little bit from the time I pitched it to them. Some of it was aesthetic. What I had pitched to them were the same drawings, but with very dark black lines. The eventually published version had greenish bluish lines. That sounds like a very minor difference, but for me it was like an aesthetic breakthrough. I wanted to draw in sort of a gestural way. I didn't understand why, throughout the entire history of comics, various creators drew in a loose gestural way and it looked fine, but when I did it, it did not look the way I wanted it to look. I realized I was drawing these black lines and then printing them using modern technology, modern paper, so they would become super, super deep saturated black almost to the point of being like a spot varnish and it just made it look really—it separated the line work from the color. It was like they were on two totally different planets. I realized that the black line that you would see in an old comic book or an old comic strip wasn't actually black. When it was printed on newsprint and the ink wasn’t making great contact with the paper and the ink was being absorbed, it was actually more like a brown. It was like a brown. So, you could have a thick, gestural, loose line and it would sort of blend with the colors in a really nice way. Instead of having a black line, it prints as a colored line. So, the right color to me was blue with a hint of green in it. After that, I feel like the aesthetic really gelled and then that kind of became my aesthetic for a while, until, eventually, I got to this sort of pencil aesthetic which kind of had the same outcome of bringing the color and pencil closer together.

I don't know if any of those companies that rejected it would have identified that as a reason why they rejected, but to me it didn't work with the black line, but it did work with the blue line.

Can you give me an example of an artist who you feel succeeded with this gestural approach that you mentioned?

A lot of Kirby inkers. George Bell Roussos. I’m thinking more like Golden Age stuff, like Simon and Kirby. And then like a lot of comic strips. I don’t want to compare myself to any of these artists, but like Dick Ayers inking Kirby, like early, early Kirby Marvel stuff, like from the early 1960s Marvel, before he started working regularly with Joe Sinnott. Some of Chic Stone’s stuff is pretty slick and pretty on the money, but some is a little looser.

I was looking at the original art, too, and the original art is drawn really big, so I thought maybe that's it, maybe I need to draw really big, so I was drawing on super large pages. The aesthetic of comics at the time of the late nineties and early 2000s had sort of become making the line work thinner and thinner and thinner, like really thin lines and then, if somebody did use thick lines, they’d be very precisely placed. There wasn’t room for thick, loosely applied lines because it just looked wrong with that black ink. Like, if you're going to have your stuff, you know, super, super, super defined, then it has to be perfect. It has to be razor precise.

It felt softer to me.

Softer, exactly. I compare it directly to Gødland. Some people tell me they prefer the Gødland aesthetic, crisper, darker black lines, but for me personally, I far prefer the American Barbarian approach and even the pencil approach that I use now. I think we had one or two chapters of Gødland to go when I started working on American Barbarian. Joe Casey really liked the black line and I had a hard time selling him on this new green line. I wanted to go with the green line and he just wasn’t on board.

In retrospect, it seems like a very obvious thing but at the time it was kind of a revelation for me.

It was a matter of matching your artistic approach, which was informed by certain artists of the past, with the existing technology of today. Is that right?

It was a matter of matching your artistic approach, which was informed by certain artists of the past, with the existing technology of today. Is that right?

Yeah, getting it to line up with the technology. I feel like that's where I'm really at now because I can take really good advantage of the technology and the precision. What the precision allows you to do is it allows you to be very subtle. You can be very subtle and still have it be legible. The way I was drawing, there wasn't room for subtlety. I was drawing as if this thing was going to get bad reproduction, but it wasn’t. It was going to get digital, high-fidelity reproduction. So I had to add imperfections. I had to add, like a yellowed paper texture. I had to age the art, distress the art, and there's a learning curve with new technologies.

You created this with the ultimate intention of print, but you knew that it would first exist digitally, at least for a while. Maybe these are also considerations you make with your other work, given the various ways that readers might consume things now, but what considerations do you make in terms of print versus digital?

What I found was digital reproduction, being on the screen, is an extremely flattering format. Things that maybe don't look as good in print look amazing on the screen. It's backlit. It's got a range of colors. It's this luminous version of your art. Digital felt really bulletproof, like everything looked good. So, I would put most of my energy into making sure that the print version looked good because so much can go wrong with print. I would focus on making it print worthy, but then I found that some of the things that I did for print ended up working really well digitally, like the vertical scroll. When you take what I had drawn for print and take it apart and line things up vertically it would serendipitously end up in these really great compositions. And it makes sense because there's the regular print reading, to the right and down. So for the down part, having something that just keeps going down and down and down, it does work. There would often be, without any planning, surprises at the bottom. Intuitively, I started coming up with things that would really work well in digital but still worked in print.

Doing web comics really invigorated my whole process and my whole creative world at a time when I felt like I really needed it. I was feeling burnt out. Sometimes you're just kind of running out of steam a little bit and when I was getting close to the end of Gødland, I was really running out of steam, running out of juice, creatively. To be that close to something that I'd already invested a lot of years in, but still being like a year or two away from the end - the last eighty pages of Gødland were the hardest eighty pages of my career.

Financial constraints notwithstanding, can you envision yourself doing something exclusively for digital release as some kind of webcomic? Did it open you up to that great a degree?

That's a good question. If you had asked me that two years ago or three years ago, I would have said no, there’s got to be a print component. I mean, I don't see any reason why something has to be exclusive to anything. That’s a tough one. I'm way more process-driven now than products driven and that's just the result of the past couple years. Working on Go-Bots and then Fantastic Four was really going full bore into the process and letting the chips fall where they may as far as the product. I guess I could. If comics just existed as something on somebody’s tablet, that wouldn’t be the end of the world.

You seemed to hint that you took American Barbarian as a chance to tell a story with a narrower focus. It was not as sprawling and definitely felt more linear than some of your other work. Did the increased linearity and rigidness have an invigorating effect on you?

Yeah, I mean it was very meat and potatoes. I have this story to tell, now let me tell it. Also, I wanted to do something that had a high concept, that I could just explain in one line, something that had a hook to it. That came out of my experience at conventions. People ask, ‘Oh, what’s your comic about?’ There would be a lot of explanation of things and I realized the power in being able to say, ‘He's American Barbarian.’ It's really just two words and it’s a strong visual. He’s going on his adventure. There’s nothing complicated about it.

Despite the narrative straightforwardness, there are still a number of stylistic experiments in American Barbarian. There are elements of photo collage. There are watercolors, which lend a kind of dreaminess to it. There are what appear to me as photographs that are painted over. How did you pick your spots to for these? Did you find an excuse for them simply because you wanted to try them? For all its straightforwardness, the whole thing feels comprised of moments for you to flex, so to speak.

Modern printing allows for subtlety and so I wanted to look at different ways of making an image. I think I was doing a page a day with this and it would be kind of like I'd wake up in the morning and say ‘Okay, here's the page that I'm doing’ and it was whatever I felt like doing that day. Whatever way I felt like creating that image, I’d go with. I think part of the web serialization is like that.

I really felt a direct involvement with the audience. For the first time in my career, I was getting instant feedback, where I make something, put it up and then immediately get reactions. That was a first and it was intoxicating. It gave me energy and fueled the work and it made me want to be daring and try different things, knowing that, if something didn't work, I could always change it because it's not it's not set in stone. It's not printed. It's not engraved yet. It was just like a real freeing up. I had very rigid set of self-imposed rules that I'd been working under my entire career that I was just freeing myself of.

You say that the feedback invigorated the work, did it inform the work in any way?

It had to. When you’re playing to a crowd, you can’t help sort of leaning in certain directions, like ‘Okay, yeah they’re really going to like this.’ I don't think it changed anything significant about the story or the plot, but it had a holistic effect. It felt more like performance art, where, up until that point, comics were such a hermetically sealed thing where I’d work on something for months and months and then by the time it gets to reach the audience, I’ve already moved on to other things. With this, I’d draw it in the morning, post it at some point during the day, and then get feedback right away.

With this approach, especially in contrast to Gødland, a monthly book, did you feel any deadline pressure?

Just that pressure of knowing people were waiting for the next day’s page. It was a manageable pressure and it was a healthy pressure. It helped it and it didn't get bad. It never got to be too much. It was a good pressure and a gentle pressure that kept me moving forward.

The only real deadline pressure was towards the very end, when me and Chris Pitzer from AdHouse were putting the book together. I did have deadlines for the thing to ship. I needed to wrap it up. There was some of that kind of pressure that makes your stomach kind of churn a little bit at the end, but that was the only point where there was.

When you’re in the grip of that spirit-crushing deadline stuff, how does that affect your work?

I think for any artist that's an ongoing relationship that you have, your relationship with the stress or the pressure, and you find different ways of dealing with it and you get better at it as time goes on. So, I've gotten way better at it. I’m really good at putting it in the right perspective, but you have your moments where you don't handle it as well.

In the case of Gødland, I just wanted to get it over with, so there were parts of Gødland that could have been better, that I just had to get through, so I got through them. But then also sometimes something really beautiful can come out of the struggle. There were parts of the last few issues of Gødland where I did things that I'd never done before that I was really proud of, that I think were a result of being in the crucible.

I found there were a lot of humorous moments in American Barbarian. Can you speak to your sense of humor and maybe your relationship to comedy?

My personal taste in comics is to minimize the comedy. I think the best comedy just emerges. I'm not a huge fan of people trying. Gødland had a lot of comedy in it, but a lot of that comedy came from Joe. Like, compared to 8-Opus - 8-Opus was very straight laced, very anti-comedy, but some outlandish crazy stuff happens and that would be the closest it came to comedy, but, with American Barbarian, I wanted to just unbutton my top button for a second, loosen up a little bit, and think about comedy as sort of a lubricant or a sweetener.

A lot of times people read something and they aren’t sure what to do with it. I like to loosen it up a little and let it be funny. Prior to this, I was such a serious world-builder. I was so serious about world building that I was afraid that too light a touch would undermine the world building and the plot and the pace. I just realized it would be okay. Media in general, especially adventure stuff, is never taken that seriously. Like, James Bond is pretty light. Star Wars is pretty light. I wondered what I was trying to make, you know? Something like Dune that was so serious you couldn’t relate to it at all?

I was struck by the strength of the character designs in American Barbarian. We’ve discussed your sense of play on other occasions, but in American Barbarian, I felt like it was especially strong, almost like you were prototyping a line of toys, or something. Can you talk about what informed these designs? I wonder if these were designs you accumulated over the years and you were drawing from different eras of your development as an artist.

Some of it came from dreams. Two-Tank Omen, the villain of the piece, was something I dreamt. A lot of the looks were made up on the fly. American Barbarian - that character’s look - is something I’d been working on for a few years leading up to this. A lot of it was improvised.

To the thing about it being like a toy line, one of the conceits that I had early on — I don’t know that it made its way into the final form - was that each chapter of this was like a mini-comic that comes with a toy, like a He-Man figure or Micronauts, or something, but that it’s not so much the comic that came with the toy, but the child’s memory of what that comic was, their incorrect recollection of what happened in that comic. It’s a little bit weirder, a little more dangerous than the comic actually was. I think we've all had that experience where there’s something that you were really into as a kid that you haven’t seen in a long time and you have all these ideas about what actually happened and then you find it and it’s not at all what you remember.

I had that experience with the Sid and Marty Krofft stuff: Land of the Lost and H.R. Pufnstuf. I had that experience with Thundarr the Barbarian. These things are huge and mythic in your memory and along comes YouTube or DVD compilations and you can finally see this stuff after a couple decades and you can see how threadbare it was and how your childhood imagination was filling in all the gaps to make it into something epic.

You used the term high-concept earlier to describe American Barbarian. This story feels very allegorical. Do you care to speak to any of the underlying themes or aspects of American Barbarian?

You used the term high-concept earlier to describe American Barbarian. This story feels very allegorical. Do you care to speak to any of the underlying themes or aspects of American Barbarian?

I’m a fan of the post-apocalyptic genre. Since American Barbarian came out, that genre has exploded. Like everything, it’s proliferated to the point that we’re almost tired of all these post-apocalyptic stories, but at the time I made it there was still a little bit of freshness left in that.

What I responded to in that genre was that it was an opportunity to remake the world, to have a fresh start and remake it from all the bits and pieces that came before it. You could take something from a thousand years ago and marry it to something from three years ago and then marry it to something that hasn’t happened yet. It’s also got elements of the Western. In barbarian stories, the world you’re showing is familiar, but you’re not restricted by the rules of the world as it ever was. In a lot of ways it mirrors post-modernism, so American Barbarian was kind of the meeting point of those two things.

Can you see yourself telling more stories in this world or replicating the conditions under which you created this?

As far as sequels, I have ideas for sequels and I have different ideas of what I would do for follow-ups, but I went into this with the idea of making a standalone thing that’s just it and I feel like it’s stronger as its own thing and it feels like a sequel would take something away from this. I can't rule anything out in life. So, there could be a follow-up, or maybe there won't be a follow-up. I like the way it ends. The ending feels complete, but has some ambiguity to it.

As far as like replicating the conditions, that's what I’ve been trying to do ever since. Everything I’ve done since then, I approached hoping to get the same sort of thing where I figure out the whole story from start to finish, work out every beat, and then execute. It's just that everything I've done since then has been for a company. This was done for myself and I sort of connected with Chris Pitzer and AdHouse to get it published, but it wasn’t like Transformers vs. G.I. Joe or Super Powers or Go-Bots, when I was doing it for a specific publisher and they had their timetables that they needed things by.

So, everything I've done since American Barbarian, I've tried to replicate that process to varying degrees. Final Frontier was the follow-up to American Barbarian. It was the comic I did immediately after American Barbarian. It had a similar aesthetic. It was shorter than American Barbarian and it came to me faster than American Barbarian. It came to me all of a piece without any preliminary work. On a drive home from a convention, it all manifested itself to me. That was the other time, those same conditions happened and I did at as a webcomic. But since then, that’s what I’ve been shooting for.

Your other webcomics seem to exist in various stages of completion on your website. Satan’s Soldier was completed and currently lives on your website. Princess seems like it's a work in progress as does Kirby, your Jack Kirby biographical strip [Editor’s Note: Publication since announced]. Where have these projects fallen in terms of mental real estate or priority for you? Do you see them as proofs of concept for later publication?

Princess is one that I plan to go back to. That's like my most recent fictional creator-owned thing and I was just sort of getting that started and there's more I want to do with that. So that one’s a priority. Final Frontier and Satan’s Soldier are so long ago, like 2012 or 2013, that I don't feel like they’re any kind of big priority. They're finished. I’d like them to see print in some wider format. I’ve talked to publishers, here and there, about that, but my priority is always about creating new work, so it’s just a lower priority. Satan’s Soldier was something I just did on a lark that ended up becoming something really different and something I'm really proud of.

Was Final Frontier meant to be a companion to American Barbarian? I get the impression that they may exist different ends of the same universe or timeline.

Yeah, I mean it's not like a sequel or anything like that, but I thought of it as a companion piece to American Barbarian. I developed this drawing and coloring style for American Barbarian that I really liked and I was about to move into a different style, a different look, but I thought that maybe I could do one more thing using that style because I probably wouldn't be going back to it ever again, so that’s what Final Frontier was. It was sort of tangentially connected to American Barbarian and, yeah, you could read it as a prequel, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be read that way.

To me, Final Frontier had similar things to say about Pop Culture. In Final Frontier, the characters are bandmates. The villain puts his captor in a pinball prison. There are all these reference points that today would be read as Pop Culture, but that in previous years, maybe a generation before ours, would be read as trash culture. I frame it this way because I think that this work, like much of your work, is informed by that era when this stuff was regarded as trash culture. American Barbarian and, to a greater extent, Final Frontier reminded me of artists like Coop! and Robert Williams. What gives these things like comics, rock and roll, pinball, hot rods such lasting relevance?

They maybe weren’t the direct product, but they were like an offshoot product of the era of advertising, like the Mad Men era, where you’d have illustrators and writers, like the best of the best, recruited into these commercial venues. I didn’t go to Art School, though I majored in Art, but the art schools that were very successful for a long time were fueled by this idea that there was this huge market for artists and you could go work for an ad agency or you could go work for some company’s in-house art department.

I feel like the art of Robert Williams, for example, is informed by that world. There’s a rigor to it that comes from having a lot of super, super skilled visual craftsmen. It's filled with commentary on advertising and pop culture and corporate cultures. It’s all tied up in that era. It’s like somebody who is a Divinity School dropout, or something. It's like they came out of this factory that produces a certain kind of rigorous thought for a very specific purpose, but they learn everything they're going to learn and they break free to create their own thing.

It’s the creation of a whole new application of a trade in service of a personal vision, rather than a commercial one?

Yeah, exactly. You're swimming in this pool of high technical ability and razor sharp focus that’s, like, utilized for all the wrong things. You take those things and apply them to something more subversive.

It's sort of like the plot of the first Star Wars movie, an aspect of it that doesn't really get explored. Luke was ready to go to the Imperial Academy to learn how to be a tie fighter pilot. That was the career path he was on. And what his friend Biggs did was go to the academy, learn everything there is to know about how to fly a spaceship and stuff, then jump ship and join the rebellion.

Using the system’s tools against it. Subversion.

Yeah, or at least doing something interesting, even if it's not specifically subversive. You're taking these skills and doing something worth doing with them.

Democratizing the tools.

Yeah. I feel like in different eras, there’s a different—this era isn’t producing artists that make work that looks like the work that was done by the EC Comics artists. Each generation has a commonality because they are swimming in the same pool. And it's possible to apply a lot of effort get your stuff to look like it’s from a different generation, the prior generation, but a generation is going to tend to produce creators that seem like they're coming out of the same tradition or the same school.

What do you think are the commonalities of your generation of cartoonists?

The big thing is just being well-versed in the history. We're living in a time when you just have the ability to learn everything that's out there about whatever field you’re going into. It’s at your fingertips. I see that in my generation of people. They are versed in the classics of Comics and the classics of Pop Culture and Cinema. You’re not just limited to whatever happens to be showing on television, like you were if you were coming out the sixties or the seventies.

Of course, it’s funny when you can tell everyone just saw the same documentary on Netflix, or something. You start to hear people speaking in a language that indicates they definitely saw this or that movie. Even though we do have access to this wider range, sometimes there are homogenous elements.

Do you think those generations that have come up with this level of access are better skilled at contextualizing it, whether they’re doing so subversively or to make a point about where it fits in a canon? Ben Marra’s work, for example, I think made the trash action thing into a different kind of artistic statement than the source material from which he draws.

There’s definitely an embracing of trash, at least within a segment of my generation of cartoonists. That feels like something, though, that is one of those things that goes in twenty year cycles. Every twenty years it’s like ‘Let’s do trash! Let’s wallow in the muck!’ and then the next generation is ‘Let’s aspire to pristine, utopian artwork.’ It seems like there is a back-and-forth with that, so I don't know if this embracing of trash is so new. It might be something that went away for a while and came back.

Given the referential nature of much of what is going on today, what do you think the legacy of this era is going to be?

That’s a really good question. I think you're going to have a lot of really solid, high quality work that has legs that people will enjoy and that won’t just become trash on the pile. I think that some some classics will come out of this era. It's not fair, but work that is self-aware and building on a tradition of things, it tends to be really good. It tends to be really polished, ambitious, and well-executed, exactly the sort of things that become classics. It's a little bit unfair because it is built very squarely on the shoulders of giants and it's definitely built on what came before, but that just seems to be how it is. So, I think there will be some very readable things.

But, you know, sometimes I wonder how much real, real, profound innovation goes on. Maybe it’s the benefit of hindsight, but I look at different eras, and see people just trying everything, just just going for it, and doing crazy things, and I feel like this era is a little bit safe, a little bit tame. Again, maybe I'm just not looking at the right things. Maybe that's just how it looks to me.

Are you speaking in terms of mainstream or art comics or kind of across the board?

All of it. The mainstream stuff I couldn’t judge more harshly. That stuff does not bear up very well under scrutiny, but even the art stuff tends to fall into these groupings and follows trends.

Final Frontier felt very polished, while Satan’s Soldier felt like you were shooting from the hip. Satan’s Soldier feels like your most experimental work to date, but it also feels very personal. What was your process in creating Satan’s Soldier and what drove your choices in regard to your use of unorthodox materials and techniques. For example, I saw you were drawing on backing boards at one point.

Yeah, that was a reaction to what I was able to accomplish with Gødland. In the back of the Gødland collection there would be sketchbook stuff. To me, that stuff from the sketchbook always looked so much better than what was in the meat of the comic. The stuff that we put a lot of blood, sweat, and tears into, the stuff that we really labored over, didn't look as good as the things that were sort of from the gut, dashed out, direct, just getting it onto paper however you can. It didn't look as good. It wasn't as alive to my eyes.

From the people whose sketchbooks I’ve seen, I feel like that’s true for maybe everybody. Sketchbook stuff is so much more fun to look at. It’s objectively more attractive to the eye than the things they put all of their effort into, so I wanted that with Satan’s Soldier. I wanted that with American Barbarian to an extent, too, but on Satan’s Soldier I really went for it.

Like you said, I would just use whatever piece of paper was at hand, and if there was a crease, or smudge, or some printing on it and that ended up in the final work, so be it. The work was alive, like a living document. I think that was an end result of coming of age in this era where digital technology was brand new and the idea of making something that looked like it was made out of machine was so attractive. It's like ‘Oh, yeah, like I want my stuff to look legit. I want it to look like it's perfect and mechanical.’ Then you see everything you lose when you do that. It took me years of working in that way to see what gets lost and I reacted against it. I miss this the evidence of the human hand. That's such a beautiful thing and let's get it back in our work.

Did Satan’s Soldier come to you all at once?

Did Satan’s Soldier come to you all at once?

I mean, I was just kind of playing with Superman tropes. I always felt Superman is just done wrong. Superman could be the coolest comic ever and it rarely is. There's a handful of good Superman comics out of however long there have been Superman comics. So I was just playing with those Superman riffs in my head, like being on a walk, thinking about Superman and what it is to me and for me personally and how I’ve encountered the work.

I'd read these collections of old Superman stories, stuff from the fifties and the sixties and the seventies, and they’re these sort of silly fairytale kind of worlds, like a Sci-Fi Space Age fairy tale. Then I'd be reading Alan Moore or Frank Miller things, like these dark eighties takes on things. Satan’s Soldier was a blend, just marrying all those things together. It was a thought experiment. So, I thought ‘Okay, let me make a little comic about this.’ I had been doing experiments with webcomics, where I’d get an idea one morning and just make a webcomic of it and then it would run its course and I’d come up with something else. Satan’s Soldier was just going to be another one of those. Then I started working on it and maybe ten or so pages into it I was thinking ‘I'm really on to something here.’ It turned out way better than what I had envisioned. I thought I was just making a goof or a lark and it ended up that there was something really special happening.

But it did not end up being published in print?

Just self-published. There’s five issues total and I printed four of them and sold those online and at conventions and stuff.

I have to imagine that a big part of the draw of putting out a comic essentially for free on your website is in the feedback that you’d get for it. What does a validating response look like to you?

It would be somebody, first, saying they really enjoyed it and then naming some things I put into it that aren’t super obvious that they picked up on. That’s like the formula for a good response, as far as I’m concerned.

You are also working on Kirby, a biographical piece on the life of Jack Kirby, still a work in progress. From what sources are you drawing to produce Kirby?

I didn’t interview Jack Kirby’s children. I didn’t interview Stan Lee, or anything like that. It’s just based on stuff that’s out there: fanzines, interviews, various books on the subjects of comics, in general, or Marvel comics, or Kirby, specifically. And, of course, the Jack Kirby Collector, because that’s kind of a gathering point of every imaginable kind of information on the subject. That’s kind of the central repository of Jack Kirby knowledge. The same sources that everybody has access to. I wanted to do a comic of the legend of Jack Kirby, what we know about Jack Kirby and the stories he’s told and the stories people have told about him and see what that looks like as a graphic narrative.

In Transformers vs. G.I. Joe, I got a lot of storytelling background from the the Director’s Commentary that ran in the back matter. With that in mind, I’d like to focus at least on the creative details of the project and what you took away from it. Can you talk about how the project came together?

Yeah, I was doing some work for IDW, like some covers, through John Barber. I kind of let him let him know I was open to other things beyond just covers. In pretty short order, he said ‘Hey, how would you like to do Transformers and G.I. Joe. He said he was in his bathtub and the idea just came to him of G.I. Joes on Cybertron, in a Nick Fury and the Howling Commandos kind of thing with me doing Kirby-style art. So he pitched that and I said ‘Yes, that’s great, that’s awesome, I would love to do that.’ Then, it was just a matter of getting Hasbro on board with that, which took a little bit of time, and then we were off to the races.

Were you working on American Barbarian at the time?

American Barbarian was finished. I had just finished Satan’s Soldier and I was working on other web comics that haven’t been completed or haven't come out in a printed form. Like, I was doing like a sort of like a Super Mario Brothers by way of James Joyce webcomic. I was just in an experimental period, yeah. I didn’t really have a job, you know?

What did research entail?

I just read every G.I. Joe and Transformers thing I could get my hands on at that point. I was just sketching nonstop. Part of it was learning how to draw those characters, learning how to draw those robots. And then part of it was just priming the pump. Like, if I just drew it, maybe story ideas would come to me. I was also soliciting feedback from people and people would offer it and tell me what they would love to see in a Transformers or G.I. Joe or telling me what that stuff meant to them. It was just like just like an information gathering phase.

And who was in that circle of folks from whom you solicited feedback?

And who was in that circle of folks from whom you solicited feedback?

John Barber, of course. And Ed Piskor. I think we might have been working in the same studio at that point. Then, at that Hollywood Theater thing, I was just hanging out and drawing for anyone who walked by, who would see it or ask me about it, getting into conversations with strangers, acquaintances, friends, you know.

What of that source material resonated? I get the impression that the Larry Hama stuff probably resonated a lot.

Exactly, that was the big thing. G.I. Joe was just really high quality. I thought it was a really good comic and then there was just so much there. There was a whole mythology and interesting characters. There was just so much to build on there. That was like a real resource. And then there was the Transformers comics. The British Transformers comics by Simon Furman were way, way more interesting than what was going on in the American Transformers comics. So I was drawing a lot from that and it was just kind of giving me insight and acquainting me with all the different characters and what I could possibly latch onto, getting my head in that world and letting the story kind of form like sugar crystals, or something.

Was that the first time you worked in that way?

Yeah, because that my first time working as a writer on a property. I had drawn other properties, but this was a very different project for me. This was the first time I was given a franchise or a brand-name thing and then had to come up with what this thing is going to be. I was really excited to work on it and I knew it was a big opportunity, but it was a little daunting. These things have big, vocal fan bases and they have these huge, huge mythologies with so much stuff to wade through, decades worth of stuff that I wasn't really all that familiar with. I had sort of a passing familiarity with it. There was just a ton of work to do and then producing a monthly comic for it, it felt like ‘Ok, this is the big time. Don’t blow it.’

Did you have parameters as to how many issues you got with it, or was the mandate to run with it for however long it would take?

No, we said we would do twelve issues - like a Watchmen kind of thing - a twelve issue series and we would try to tell a complete story. That's what I wanted to do. I wasn't really that interested in the idea of spinning our wheels. I wanted to try to come up with a complete start to finish kind of story for us to come in, do it, and get out. And just being open that maybe if I'm having the time of my life and I don’t want it to ever end, then maybe would go beyond that. But, we thought we would do twelve issues and we talked about doing a mic drop, ending it in a spectacular fashion. I was thinking a lot about various comic series and TV series where they stuck around too long and took a good thing and ruined it, so I didn't want to do that. I wanted to tell the story and then, when the story was told, step aside and maybe maybe revisit it in years down the line, but to let this thing be its own complete thing.

Am I correct that issue zero, which you released prior to the release of the first issue for Free Comic Book Day, and Transformers vs. G.I. Joe: The Movie Special, which came out after the final issue, were kind of afterthoughts or bookends to the series?

Yeah, I had a story that I wanted to tell. I had to start making the actual comic before I had every little bit and piece worked out. I wanted to have like an airtight thing before I went in and I’ve come to learn that that's just not how it is. It's never going to be exactly the way you want it. The timetables just don’t allow for that. But I had this story idea and then it was like ‘Oh, yeah, we're going to do Free Comic Book Day and we're going to do an issue zero,’ so I had this idea of how I was going to introduce the characters, so now I had to introduce them twice.