Al Feldstein, who, with publisher Bill Gaines and a small cadre of artists, revolutionized the comic-book publishing business not once but twice, died Tuesday, April 29, 2014, at his home in Livingston, Montana. No cause of death has been announced.

The first revolution came about with the inception of the “New Trend” titles from EC Comics in 1950. The second revolution came with the enormous popularity of Mad magazine and the impact it had on American attitudes.

If publisher William M. Gaines was the heart and soul of EC Comics, editor/writer/artist Al Feldstein was the company’s intellect. The prolific Feldstein edited more comics and wrote more scripts for EC than anyone. He also drew 31 comics stories, and at least 74 covers for the company.

Feldstein was born October 25, 1925, in Brooklyn, New York, and began working in comics at the age of 15 at the Eisner and Iger Studio, while still in high school. He graduated from New York City’s High School of Music and Art.

He attended classes at Brooklyn College and the Art Students League before entering the Air Corps during World War II. While in the Special Forces, he drew a comic strip called Baffy for the Blytheville, Arkansas base newspaper, designed posters, and painted murals. After the war, he worked for Iger again before moving on to Fox Feature Syndicate.

At Fox, Feldstein wrote and drew Meet Corliss Archer (a “good girl” comic based on the long-running situation comedy radio show), and Junior and Sunny, two “good girl” teen humor titles. One day, freelance letterer Jim Wroten informed Feldstein that their mutual employer, the sleazy and exploitative Victor (“I’m the King of Comics!”) Fox, was having financial difficulties that might interfere with Feldstein’s income.

So, by March 1948, Feldstein was presenting samples of his work to Bill Gaines in the hope of doing comics for EC like the ones he’d been packaging for Fox and other publishers. Gaines was glad to see the talented young artist because at that point he had been running EC for all of seven months, following the unexpected death of his father, Max C. Gaines, and he needed to build up his staff.

Feldstein’s samples, loaded with buxom young women, impressed Gaines enough to assign the young artist to write and draw a new teen comic, Going Steady With Peggy. But upon learning that sales of such material had tanked, Gaines pulled the plug on the project before Feldstein could do more than pencil the first story and a cover. Gaines offered to pay Feldstein for his work, even though Gaines had no use for it, but Feldstein demurred, which made a great impression on Gaines. Feldstein was a good fit for EC, and he and Gaines got along well from the beginning.

Feldstein already had plenty of experience as an artist, and he got right to work, churning out stories for Saddle Justice, Gunfighter, Crime Patrol, and War Against Crime. For the first two months or so, he worked from scripts by veteran comics writers such as Ivan Klapper and Gardner Fox. But, sensing an opportunity to make extra money and find more creative satisfaction, Feldstein asked Gaines if he could write his own scripts. Gaines readily agreed.

Initially, Feldstein only wrote scripts for the stories that he illustrated but he covered all of EC’s bases at the time: Western, crime, and romance. Before long, he was scripting stories for other EC artists. It was only the beginning.

Gaines had been resistant to taking over his father’s business and played only a desultory role at first, but he came to fall in love with comics and was eager to move beyond his business role as publisher and be involved creatively in his comic books. He and Feldstein became fast friends and collaborators.

In 1950, Gaines and Feldstein launched new horror, crime, shock and science fiction comics. This “New Trend” boosted the company’s sales and shook up the comics industry. Their explicitly gory, yet tongue-in-cheek horror titles spawned countless imitations.

Their newfound success brought with it the need for Feldstein to write a script every day, Monday through Thursday. On Fridays, he attended to other editorial duties.

Gaines and Feldstein began plotting stories together, and Gaines loved nothing more than the almost daily back-and-forth of working out a story with Feldstein. Feldstein enjoyed it, too, and took special pride in turning in a fully scripted story that Gaines liked.

Feldstein recalled it this way to Frank Jacobs in The Mad World of William M. Gaines (1972): “When I wrote a script, my first and foremost motivation was for Bill to read it and enjoy it. Bill supplied my need for a father. For this I did all I could to earn his love.”

Gaines made Feldstein an assistant editor and, later, an editor. But it wasn’t Feldstein’s title that mattered. It was the personal and professional relationship that he and Gaines shared — a unique creative symbiosis that developed a remarkable way of working together to turn out a complete comic book every week, as required by EC’s schedule. It was, by the accounts of both men, a hectic, joyful, and creatively satisfying partnership.

Gaines saw it as his job to be the “springboard man.” He was taking prescription amphetamines at the time in an effort to curb his appetite and lose weight. He suffered insomnia as an unfortunate side effect, so he spent his sleepless nights reading horror and science fiction stories. A lot of them.

As he read, he’d jot down “springboards” — short, one- or two-sentence story ideas that he could pitch to Feldstein in the morning. As Gaines humorously recounted in EC Lives!, the program book for the 1972 EC Fan Addict convention, “after he [Feldstein] had rejected the first 33 on general principles, he might show a little interest in number 34. I’d then give him the hard sell […] He would normally write the story in three hours, breaking it down as he wrote it right onto [the art boards]. Meanwhile, I’d sit there … with a nervous stomach because I never knew if and when Al would come bursting back in and say, ‘I can’t write that goddamn plot!’”

Feldstein remembered it this way: “I used to drive him nuts because we would plot these together and I would say, ‘No, no, no, Bill, that just doesn’t work.’”

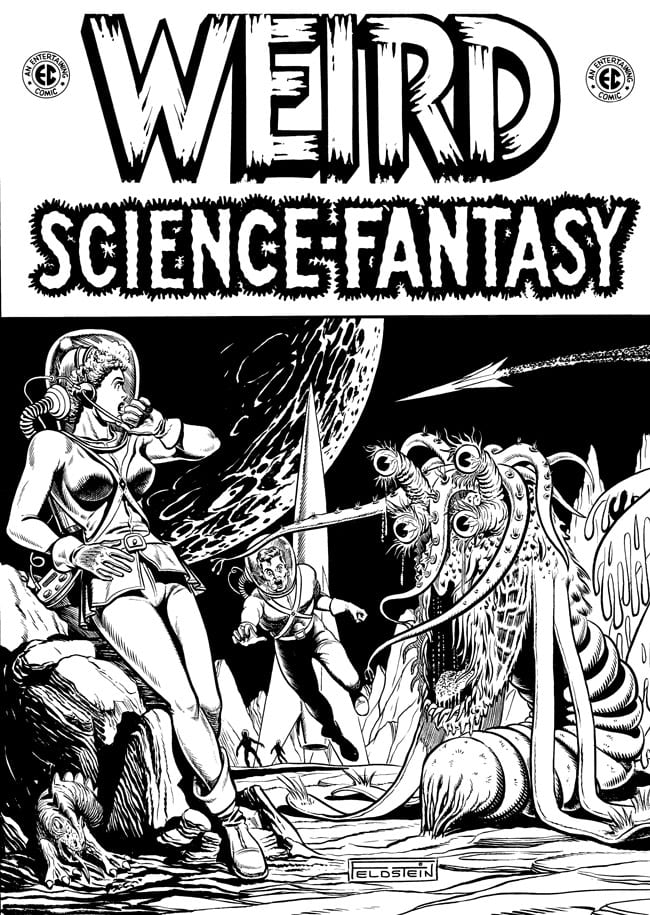

Still, it must have worked most of the time, because Feldstein wrote four scripts a week for more than four years, becoming, in the process, the most prolific scriptwriter EC ever had. The demands of his editorial and writing duties, however, forced Feldstein to forgo drawing stories around the middle of 1951. He continued to draw covers, though, for EC’s science fiction titles, Weird Science, Weird Fantasy, and their combined successor, Weird Science-Fantasy.

Since Gaines didn’t always tell Feldstein what he was reading, Feldstein often unknowingly adapted short stories by famous writers including Katherine Kurtz, H.P. Lovecraft, and Ray Bradbury. Bradbury, however, caught their unauthorized use of two of his stories, “Kaleidoscope” and “The Rocket Man,” whose plots Gaines and Feldstein had amalgamated into the story “Home to Stay” (Weird Fantasy #13, May-June 1952). Bradbury wrote Gaines a letter politely demanding payment.

Since Gaines didn’t always tell Feldstein what he was reading, Feldstein often unknowingly adapted short stories by famous writers including Katherine Kurtz, H.P. Lovecraft, and Ray Bradbury. Bradbury, however, caught their unauthorized use of two of his stories, “Kaleidoscope” and “The Rocket Man,” whose plots Gaines and Feldstein had amalgamated into the story “Home to Stay” (Weird Fantasy #13, May-June 1952). Bradbury wrote Gaines a letter politely demanding payment.

Bradbury liked the adaptation, however, and, in a postscript, suggested that EC adapt stories from his collections Dark Carnival, The Illustrated Man and The Martian Chronicles.

Gaines immediately paid Bradbury for the use of his plots then struck a deal to adapt more, at $25 each.

Bradbury’s work proved an enormous source of inspiration for Feldstein. As Feldstein recalled in his interview with Grant Geissman in Tales of Terror! (Fantagraphics Books and Gemstone Publishing, 2000), “This became the love of my life, adapting Ray Bradbury into comics. I did The Martian Chronicles, Golden Apples of the Sun, and for the horror, I was doing The Dark Carnival. And I just loved it. That was where I think my writing really started to improve, because I was immersed in his writing — much to the detriment of the artists. The old joke was that I got to write such heavy captions and balloons that all the characters had to be drawn with a hunchback … He was my idol as a writer and I kind of aped him. See, I was never a writer.”

Despite his claim not to be a writer, Feldstein went on to produce more than 500 scripts for EC.

In the meantime, the cartoonist Harvey Kurztman, who had also become an editor for Gaines, launched Mad, a satirical comic book which Gaines later turned into a magazine at Kurtzman’s urging.

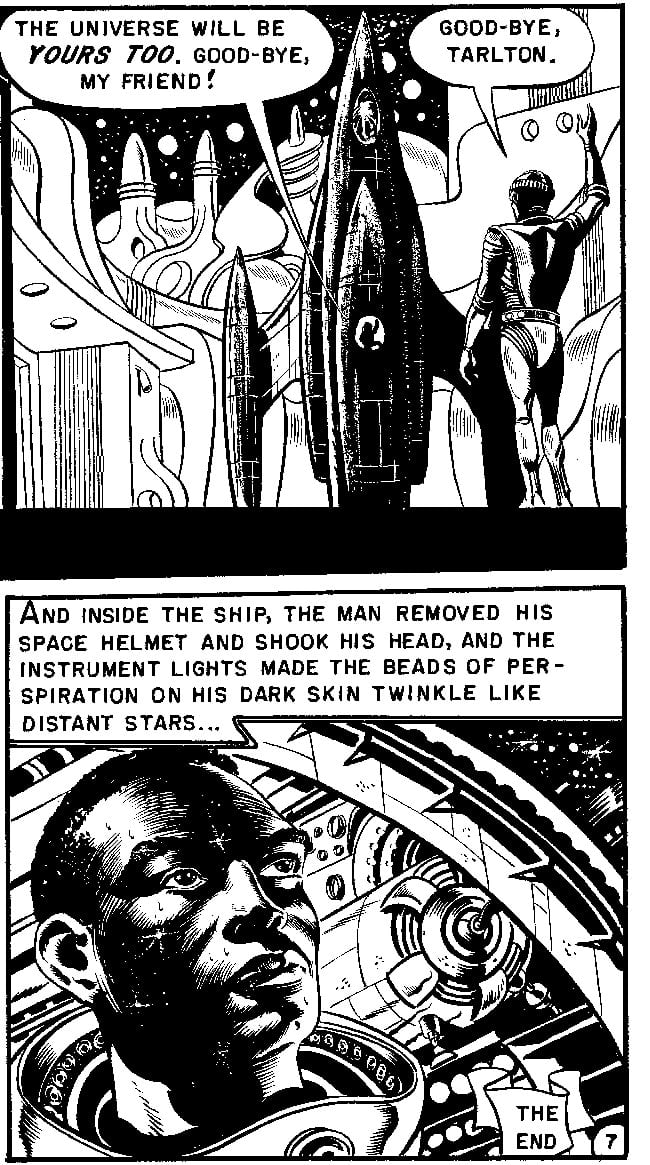

In 1954, the comic book industry came under fire by people seeking to place blame on the rise of “juvenile delinquency.” EC, because of its popular horror and crime titles, including Tales From the Crypt and Crime SuspenStories, was an easy target. After televised hearings of a Congressional Subcommittee investigation, comic book publishers, including EC, banded together and created a self-censorship board called the Comics Code Authority. The Code was especially hard on EC’s material, even after Gaines cancelled the horror and crime titles and replaced them with tamer fare. At the same time, EC’s circulation plunged as wholesalers and retailers refused to put EC Comics on sale. It all came to a head in late 1955 when the Code rejected a story for Incredible Science Fiction and Feldstein substituted a previously published pre-Code anti-racism parable, “Judgment Day,” which he had written for artist Joe Orlando, to Code administrator Charles F. Murphy. In The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York, 2008) the historian and critic David Hajdu quoted Feldstein in recounting what happened next:

I said, “Bill, this is impossible. It just can’t work. They are after our ass, and they’re going to find any excuse to give us a hard time.” And Bill called up Murphy and said, ‘What the hell is going on?’

And Murphy said, “You can’t have a Negro.”

And Bill said, “Okay. I’m going to have a press conference, and I’m going to tell the public that the comic book authority is a racist authority that will not permit black people to have equal depiction,” or something like that.

After a pause to reflect, Murphy granted Gaines permission to publish the story, on the condition that the beads of perspiration on the black astronaut’s face be removed. (Feldstein’s text ended with a purple flourish: “and the instrument lights made the beads of perspiration on his dark skin twinkle like distant stars…”)

Gaines said, “Fuck you,” hung up on Murphy, and published the story intact.

That was the last comic book EC published. Gaines pulled the plug on EC Comics in 1956 and was forced to let Feldstein go, along with all the other EC freelancers who weren’t working with Harvey Kurtzman on Mad magazine.

Feldstein was at liberty for a few months, freelancing scripts for The Yellow Claw for Stan Lee at Marvel, but then Kurtzman asked Gaines for 51 percent of Mad in an effort to ensure total editorial control. Gaines told Kurtzman to go to hell.

Kurtzman had orchestrated a successful transition from Mad the comic book to Mad the black-and-white magazine, but he left immediately, with the latest issue unfinished, and he took the art staff, excepting only Wallace Wood, with him.

Gaines still had an ace in the hole, even though he may not have realized it immediately. On the advice of Lyle Stuart, his friend and business manager, and after talking it over with his wife, Nancy, Bill Gaines decided to reach out to Al Feldstein.

Feldstein was the logical choice, of course, because he had never had the kind of deadline problems the temperamental Kurtzman always ran into. Feldstein had also edited Panic, EC’s homegrown imitation of Mad.

Although he claimed not to have had much of a feel for humor, Feldstein had written about half of the Panic scripts before his workload had gotten too heavy and he’d had to pass the writing on to Jack Mendelsohn and Nick Meglin.

Gaines drove out to the Long Island Railroad station where Al Feldstein was returning home after a fruitless day of pounding the pavement for freelance work. In The Mad World of William M. Gaines, author Frank Jacobs reconstructed their momentous reunion:

“Al, Harvey’s left and I’d like you to come back. I don’t know if we’ll continue with Mad, but we’ll do something.”

“We should do Mad,” Feldstein said.

“Well, whatever we do, you’ll go all the way with me.”

Feldstein went right back to work, faced with the immediate problem of rebuilding a staff. In 2007, he described the challenge to interviewer Jason Heller for the A.V. Club.

“For an atheist, I thank God all these guys showed up: Don Martin and Bob Clarke and Dave Berg. Writers started coming in, and Mad was progressive with its success. When I had been out of work, I imagined starting an adult magazine that would be a showcase for iconoclastic humor, featuring people like Lenny Bruce and Ernie Kovacs and Bob Newhart, who were beginning to crack the establishment with their humor. When Bill asked me to take over Mad, I immediately started to get name-people like Ernie Kovacs to write for me. I hesitated at Lenny Bruce. [Laughs.] I didn’t want to get into trouble again.”

Gaines was less involved creatively with Mad than he had been with the comic books and, starting in 1956, Feldstein guided the magazine to become an American institution, skewering movies, TV, music, advertising, politics, and just about every aspect of popular culture. The Mad artists, including Al Jaffee (Mad Fold-Ins) Mort Drucker, Dave Berg, Antonio Prohias (Spy vs. Spy), Don Martin, and others virtually became institutions themselves.

Under Feldstein’s editorial stewardship, Mad grew to become one of the most successful humor magazines of the 20th century, with a peak circulation of almost three million copies an issue. That popularity paid off for Feldstein because the deal he’d negotiated with Gaines resulted in Feldstein becoming one of the highest paid magazine editors in the world.

After retiring in 1984 and moving, first, to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, then to a 270-acre ranch in Livingston, Montana, Feldstein fulfilled his life-long dream of becoming a fine artist and painted award-winning wildlife and Western scenes. He also occasionally accepted commissions to re-create some of his favorite covers from EC Comics. In 1999, he received an honorary Doctorate of the Arts degree from Rocky Mountain College in Billings, Montana.

In 2003, Al Feldstein was inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame. In 2011 he received the Bram Stoker Award for Lifetime Achievement from the Horror Writers Association.

He remained a popular and much-beloved figure in the comics community and occasionally attended comic book conventions. He had been initially scheduled to be a guest of honor at the 2013 Comic-Con International: San Diego but was “personally disappointed” when he had bow out “due to poor health,” he wrote to Fantagraphics editor Michael Catron in an email last May.

His survivors include his wife, Michelle; a step-daughter, Katrina Oppelt, and her husband Bob; and two grandsons, Colton and Winston Oppelt.

Feldstein was cremated, and his ashes will be spread on his beloved ranch. There will be no public memorial.

Michael Catron contributed to this article.