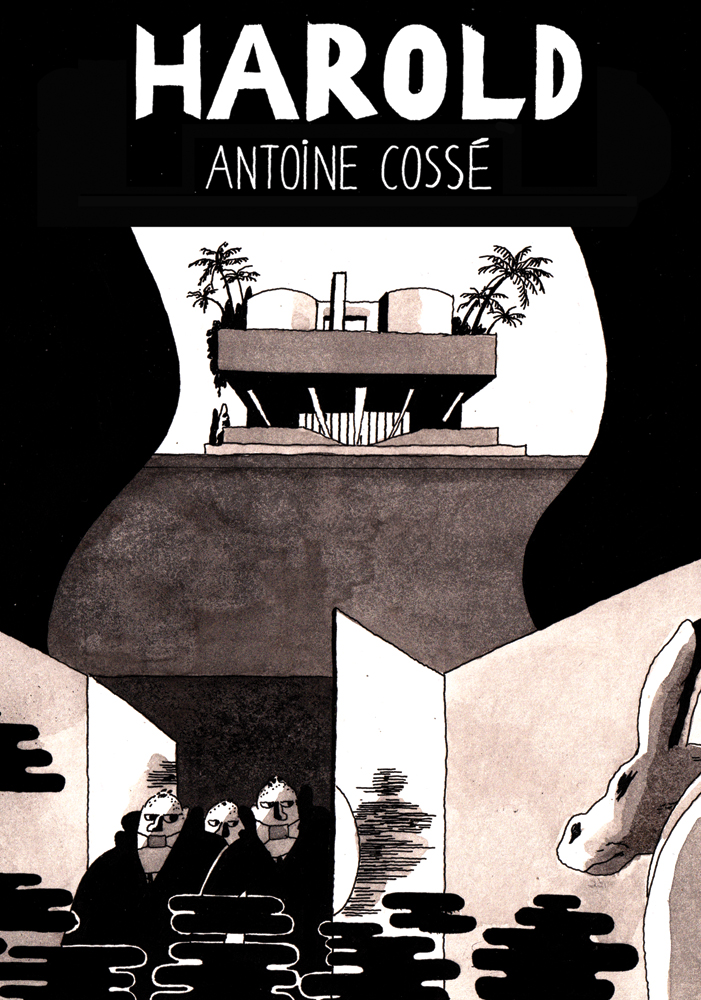

My first reading of Showtime came after a long period away from comics--and what a book to come back to. Antoine Cossé's newest, concerning a journalist travelling to interview a celebrity magician, is rife with ambiguity and fascinating implications and tones: existential, funny, satiric, exciting... This book positively courses with a shifting, restless drawing energy that makes every page worth a longer look than you're likely to give it on on a swiftly paced first read--such is the book's ability to carry one along.

All the same, the thing is totally inviting; for all its shifts in style, Showtime feels remarkably controlled in the way it brings the reader in, an unusual quality in a work this inquisitive and self-aware. After finishing the book, I was immediately interested in discussing it with Antoine, knowing all this couldn't have been easy to achieve. I'm grateful to Antoine for his participation, as he was kind enough to Skype over the book this past December and to correspond over the transcribe as I edited after.

George Elkind: Showtime, [as friend and TCJ peer Matt Seneca observed] has a very quick reading pace, or “flow” to it, so that taking it in feels very intuitive. I assume drawing it was not the same way. How did you achieve that effect--was it through scrapping and re-drawing or some other means?

Antoine Cossé: Yeah, yeah. Well, with this book it was. But it depends. Sometimes a book is quite linear and I do it quickly, like the smaller books, Mutiny Bay was the first big one that I did--there was quite a lot of rewriting, but that was really hard. So it’s nice if you feel that [with Showtime]--that it feels “flow-y” and that it’s got a nice pace to it. Because I really struggled with it, it was quite hard.

Yeah, the movement’s almost like--you could compare it to manga, at least in the popular conception. By which I mean... “page-turning.”

Yeah! Which is about the level to which I know manga. [both laugh] Anyway--I love it, but I don’t have an extended knowledge of it--like the rest of the guys at Breakdown have, or something.

Sure. Were there any particular models for the pacing? Or you just knew that you wanted it to flow quickly?

No, I always find it really important with comics for me. The pacing of it, it needs to… I don’t know really how to explain it. I need to be able to read it in a certain rhythm that I have in mind, or… when I start it. And then I need to edit it to make it feel like it’s flowing the right way, and it [the process] is very long. So, it ends up-- Showtime ends up being really quick to read, which is quite funny.

But yeah, it was hard. Because I started ages ago and then I did a mini with it. And then I really shuffled the order a little bit, to get that pace.

Sure.

Yeah, like scrapping and then changing the order. And then by changing the order you have to re-do the whole pace of the whole book, basically. So you have to add pages in between. So I always--I don’t know… comics are, I guess, not in any way like a book or like a film. It’s kind of in between, isn’t it? So that’s it, it’s just how you read it.

I think editing is sometimes an overlooked step in the process. A lot of people don’t consider that you need to edit a comic for flow, but to me it seems really central.

Yeah.

This book kind of further complicates that by having different drawing registers. You have the more marker- or wash-heavy pages, particularly with the boat sequence. You go to pretty spare, or kind of scrabbly-looking marker drawings for a bit… How… They seem to kind of align with [some] point of view at times. What led you to--or how did you--settle on one register for a particular scene when presented with a bunch of options? Does that make sense?

Yeah, it makes a lot of sense. Because it was done over quite a long time, like a year and a half, what I was using was just what I was trying out at the moment. And then I ended up using it [a particular style or set of tools] for a particular kind of scene… maybe by scene, actually. So, yeah--the one with the fat marker is where they’re on the boat. I mean, there was a little bit of a challenge as well, to be honest, with this book. I mean, I was like “I’m gonna try all of these different things, and see if they can work--together.” So there was a bit of that and a bit of setting the mood for different scenes.

It seems tied in with ideas running through the book about art as performative--with stage magic, and with playing up spectacle.

Yes. But I didn’t want it to be done with just one kind of technique. I mean, I did that with Mutiny Bay as well, with colors at the end. The only thing I didn’t do with this book was no colors, but there was enough on my plate with black-and-white and the rest of the stuff.

So, just to clarify, you’re saying that you see the different tools and modes of drawing as reflecting particular scenes… or that they more correspond with particular scenes than a sort of character-based perspective?

No, they’re not character perspective-centric--it’s more of a scene [based] sort of purpose… or like a [theater or film] set. It’s more spatial, I guess.

Interesting. I’d been thinking of it less as different characters or as scene-based than one character in a different mood… the way I read it.

Oh. That would have been much better. [both laugh]

Well, it can function as both I suppose. That’s how I read it--or misread it, I guess.

No, no, no. Well, the different kinds of techniques, I have to say it’s a bit… it’s not rendered because… with this book while I was doing it, it felt really messy and really intricate, and that [I felt] I had to edit it in a way that feels really smooth. Because it’s not a very complicated story, but while I was doing it, it felt very difficult. So maybe that was it as well--that I was kind of touching lots of different things. Trying to make it a bit… well, not harder, but more…

More elaborate?

Yeah, more like trying out different things. I have all these people doing different styles around me, so I guess this gets in the way as well--well, not in the way. But I’m like, “ooh, I want to try that as well.” Because it gets to the point if you do a long book--for me, anyway--where you want to change [style] a little bit and you want to keep yourself interested. So that’s one way I found to do it. So, like, I would discover an artist and then I would try to incorporate what they were doing.

Interesting. Because with Showtime I didn’t observe many particular, direct references--who were you looking at, if there’s anyone you want to name?

Yeah, yeah. For example, Olivier Schrauwen. I discovered quite a lot of his stuff while I was doing it. And Blutch and Anna Haifhisch as well. And obviously Joe Kessler and his stuff, I don’t know--off the top of my head that’s the ones I was reading.

You know, I’d see stuff and I’d try different things. I didn’t really change style, but some little things I would try to incorporate.

Yeah, it still all looks very coherent--like “your” style, even if you changed modes often.

Yeah, I think that was the whole thing. “Try to keep the whole thing coherent,” that was the mission of that book. It was really cool to do it, but that was a big thing with this book.

I do think Schrauwen does something similar, as does Joe--in terms of changing drawing registers over the course of a story.

Yeah, sure. Maybe that’s what I did, I just--more than copying their style, I copied their kind of way to tell stories, I guess.

Bored by Fame

I notice you have a lot of characters who seem burdened by fame in some way: actors, M [the central magician character in Showtime]. What makes them interesting to you?

Yes, I’ve always been a bit fascinated by it. I like it, I like cinema. But I like the whole mystery around it, for example I love old pictures of sets… I don’t know, I always found it quite magical. It’s quite mysterious for me--for you, it’s probably not. But for me it is. I just like films--but I like also how they’re made. Like, for example, I draw [film set-based] stuff but I have no idea; it’s probably not as mysterious as all that. But I don’t know. I guess that’s why.

I shot a short film with some friends a few years ago, and never really finished the editing, which is stupid. But I remember one vivid sensation while I was filming it. We managed to get a lot of material for free because two of the guys that were helping are working in film, so we had a monitor, which I guess you normally don't have for a first short film... And while we were shooting I was really impressed by the difference, or the lack of difference even, between what I was seeing in front of the camera and what I could see in the monitor--which is the same image, but in two realities. It was a genuine shock.

I keep using this mechanism in my comics now, the idea of the frame or the mirror you can go through and see things that look the same in a different angle. I thought it was really magical.

I’ve been working on film shoots lately, and there’s a degree to which that kind of elated feeling doesn’t go away--even when you’re working on-set.

Yeah, exactly. Most of them… are not magical at all. But it’s quite a crazy medium. And there’s quite a lot of… I mean, I’m talking about film like the magician. I mean, M is just like… I got into a bit of a YouTube hole with David Blaine. I found it quite fascinating, quite good.

I should look into that.

...Yeah, I think that’s why. [pauses] I don’t know, is there something else? Yeah, there’s still a quite romantic notion of all that. Of the big actor, or actress, that’s still in our collective consciousness as a society. It’s there, this thing... So it’s funny to play with myth. And cinema is the absolute myth. You know, it’s our god. So maybe there’s that as well, a little bit.

And whoever becomes famous is then so intensely conscious of it that it becomes its own kind of problem, I think.

Yeah… I think they’re more bored than having a problem with their fame in my stories--I think that’s it. They’re just really bored--or, like, looking a bit out of it, really.

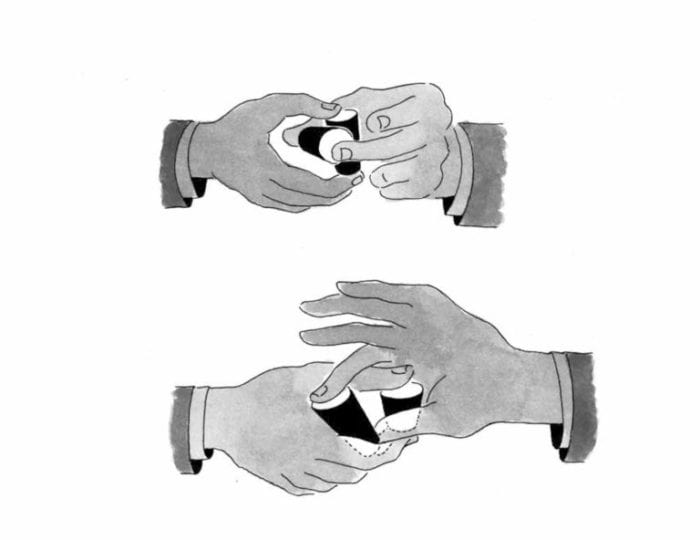

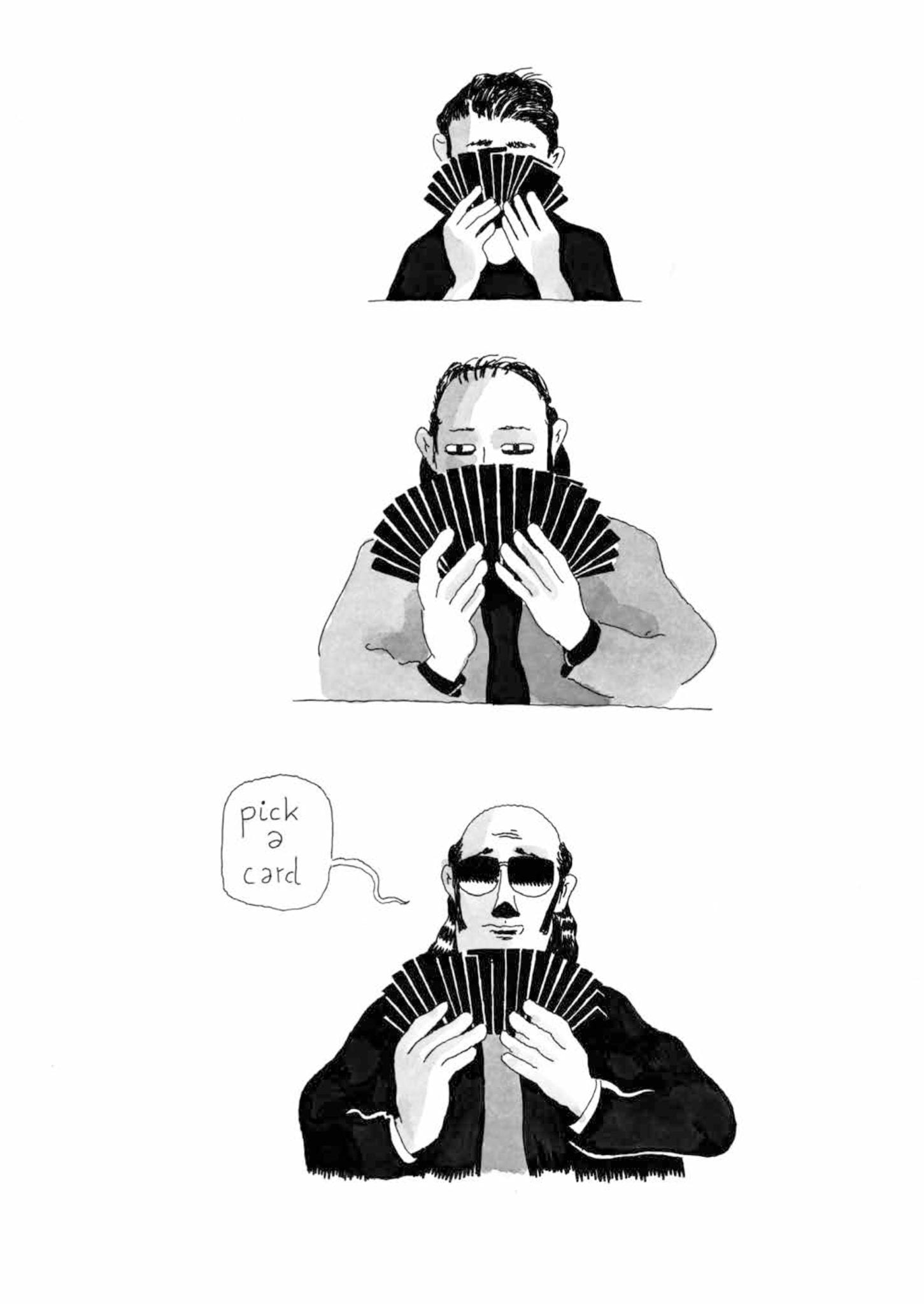

I noticed M’s tricks are all about disappearing, or absence for the most part. You also have the ship levitation, but a lot of what he does is make stuff go away, or vanish. Which seems sort of significant to me as a motif.

Yeah, it is. It’s the most incredible thing to watch, though. You know, it occurred to me when I watched, before I was doing the book, that magicians are the only people that, as you watch doing something, you know it’s not happening but you really want to believe it. I thought that was a nice thing to feel as a human. But I think it’s quite a beautiful, human thing, magic. And the most amazing thing is when they disappear, or they make stuff disappear. I don’t know, that’s what impresses me the most so that’s why it’s all over the comic, I think.

I haven’t watched much of his work. Can you talk about some of the Blaine stuff you’re into? I don’t know if it started as research, or--

No, no, it started as interest. And then--it was all a massive… it was the period that I was in France, as well. And it was about belief, as well, this book. There was all this stuff about religion in the media, and I was watching these weird tricks by magicians and stuff. So I thought, “this is us as humans. Trying to make sense of things that don’t make any sense.” So some people, do this, some people do that, you know? But I also really just like watching it [Blaine’s work]--in the 90’s when he’s in the streets doing his tricks, it’s great. Really good entertainment. It’s quite naive and romantic, really quite nice.

Yeah.

They always look a bit lost, magicians… I don’t know--I feel. They look a bit sad. Or maybe it’s me that makes them look sad.

Well, it's an unusual situation, because--like you said--you’re watching a performance and you know it’s not true, but the viewer is often bringing something to the table in terms of wanting a kind of truth. It’s hard to know what a viewer might bring to it at a certain point…

I’m still kind of fascinated by the disappearing thing--there’s a kind of emptiness, or a conspicuously empty quality to the performances. Likewise, when M does make an effort to reach out in the story--trying to change things concretely--there seems to be a clear limit on what he can do. It’s interesting to me that when it’s something really important, his attempt to communicate doesn’t quite work in the way he might like it to. It’s when he tries to make a really concrete difference for someone that he fails most visibly.

Yeah, it’s true.

[rethinking] Though it’s not a moment that’s necessarily more important than the kind of fabulous spectacle of the boat scene. I think you could see that being equally as meaningful as a life-or-death warning you give someone. You know, the event that makes their life or another that gives them a chance to prolong it… it’s interesting.

Yes, I think he’s obviously not the best communicator. I mean, is he… is he doing it through his tricks? I don’t know.

Yeah. There seem to be a few kind of ethical concerns with his tricks, like the way the women kind of disappear in an early sequence. That can be read literally as him making them disappear, or it can be taken as a kind of revolving door of women he doesn’t connect with.

It was more the second one, that he’s not managing to connect with anybody. And then he’s also doing this… slightly creepy trick. But there was a little bit of ambiguity to it, there’s a slight creepiness to him. But you’re right, this guy has obviously found it very hard to communicate with people.

I think the different frames the book has--there’s the rat narrating, and then the journalist, who lies about what seems like the central part of his story, the segment with the boat. The characters ask him if he was affected and he says “no”--I feel the ambiguity introduced by those frames frees up the style of the book more. There can be that subjectivity or variance because you don’t have to trust anything anyway, necessarily.

Yeah, that’s true... Yeah. It’s like fake news.

Yeah. [laughs] I hope there’s less of that in Europe.

Yeah, it’s a little bit like--like trying to make sense of this book. I don’t know. There’s, like, loads of stuff happening as well. M trying to communicate... Yeah, I don’t know.

Yeah, there’s a lot kind of questioned about truth, fact, story, art… kind of like in postmodern fiction. They’re all kind of equally filtered here.

Yeah, even the way we do stories right now--you’re never really off even when you’re--like, for example, I realize they don’t have mobile phones in that story.

Oh, yeah.

And, like, that’s a huge thing. But while I was doing it I didn’t even think about it.

Well, they do mention it with the boat. They say “no one took a mobile phone video,” or something.

Oh, yeah. That’s true.

Kind of on that thread, most of your stories have been kind of ambiguous in terms of the time they take place in. This one seems like the present, or future--potentially. I guess J.1137--that story seems more overtly near-future. Do you set out with a particular time events take place in, or is a matter of wherever the drawing or the story place things?

No, it depends. That seems to be the same world [as Showtime]--apart from Mutiny Bay, where I was forced to use this [historical] time frame. But the rest of my stories are all… it’s almost the same landscape. I guess it’s like a… what do you call it?

The popular term now seems to be “shared universe.”

Yeah, it’s almost like a parallel universe, but I don’t like that. It’s like it’s our world, but that’s where it’s ambiguous. You don’t know if it’s in two years, or in twenty. I don’t know, I’d like to think it’s our world.

It’s really interesting. You often have palm trees, which tend to signify LA, especially in stories with a lot of film production. And then you have elements that look more like France, or other places. But that seems convenient as a premise, since it lets you incorporate whatever you want.

You kind of serve the story as well, always. But maybe I’ll do one with, like, a particular [setting]...set really in our world. Which must be kind of interesting too. Because now I think maybe it’s just the easy way out to just do it a bit, like, tailored to yourself--I guess. Maybe I should do one that’s set in reality, like, properly.

Well, I don’t think it’s objectionable or anything. I just wondered if you had a preconception about it going in, but it seems a little more organic.

Yeah, it seems to allow me to be a bit more free in the story. You can touch all subjects--because there’s no country, we don’t really know where it is. I mean, it’s obviously some kind of Western society.

Right. How’d you settle on “Ronin” for the name of the city, was that after the Frank Miller comic or something else?

No, I thought that I made it up. But maybe I did write it from that. I’ve actually never read a Frank Miller comic! Well, I did see one, but I never really read it. So you see a Frank Miller reference, oh my god--that’s hilarious.

It wasn’t clear that was how I should read it. But it came to mind as a possibility.

Well--it could be. Why not? [both laugh] It could be, it could be Frank Miller-ish. That universe. But, no, I wanted to have something… we had a bit of a debate with the Breakdown boys, about what to put for the name of the town. I was hesitating between, Ronin, and, uh, Thebes as well. The Greek Tragedy kind of town. But then it was a bit…

Oh. Interesting.

Yeah, I think one of the next books I want to do is a take on a Greek Tragedy. I was interested in kind of introducing it by doing that [in Showtime], and then I thought “that’s stupid,” it’d be seen as kind of the first part of another book. So we decided on Ronin, in the end. It just sounded neutral enough… but I didn’t know it was a Frank Miller book.

Yeah, it’s a title of one--but it’s also just a word.

Yeah, yeah, it’s fun--I quite like it. [both laugh]

A Total Space

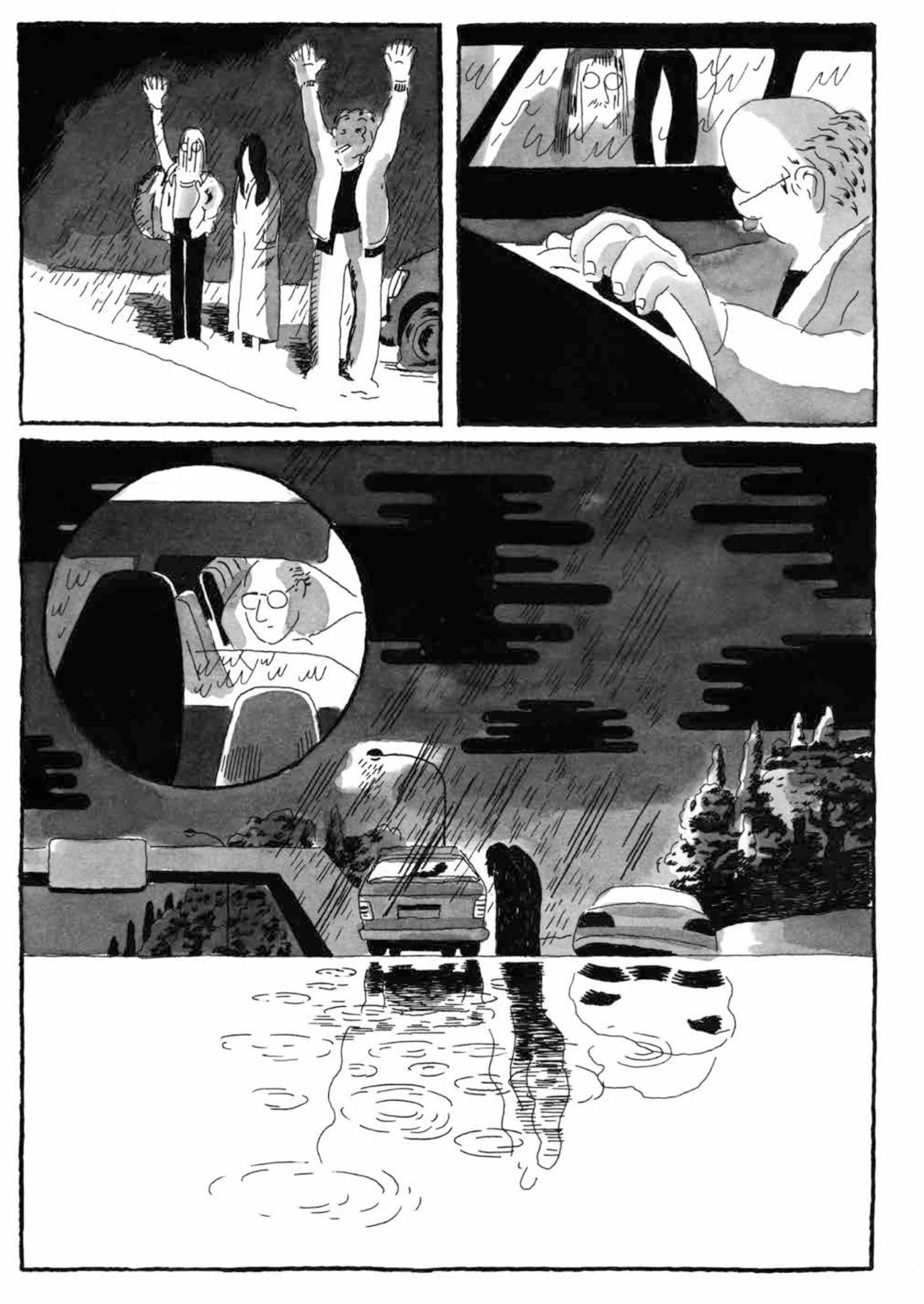

You have a lot of long drives in your comics, but I don’t associate any of the places you’ve lived [London, Paris, Turin] with long drives. Is that kind of an elaboration for you or is that more rooted in some experience?

Well, it’s both. I really like driving. I always find it very meditative--it’s like a nice thing to do. But, to draw, it’s great because it’s a total space. You can control everything and you can vary the speed. Because it’s like a thread. So I found out that, too--but I also really like drawing cars. So that’s good.

Sure.

But you also get to enclose your characters into a really close space, which is weird. Because people in cars are just a bit weird. You’re not really--it’s strange [in Showtime] because it’s his car, and they’re all strangers and they talk together. I mean, there’s different things; if you’re being driven by someone, there’s a strange kind of way of watching landscapes. I don’t know, it’s like if you’re driving… when you drive, it’s different. So there’s loads of different shifts in point of view.

Yeah, it’s kind of its own sort of altered state, I guess.

And there’s the in- and the out- of the car, when you’re [via point of view] in the car or out of the car, which I really like playing with in comics. But you’re right, there’s a lot of driving.

Yeah, it’s kind of a motif. I just watched Certified Copy with Juliette Binoche recently. Have you seen that movie?

No, no, I don’t know that one.

By Abbas Kiarostami. It’s got a lot of nice driving sequences, where they’re projecting what’s supposed to look like a reflection. There’s a camera above the car, and… I’m still a bit confused about how they did it. But it seems like they’re projecting onto the surface of the car these images of branches and things moving overhead.

Oh, wow.

It’s a really cool angle. There’s a lot of good driving footage--I’m trying to remember where they are in it… I think they’re around small French towns, I don’t know if it’s specified.

Yeah, I’d watch that.

Yeah, if you’re into driving footage, I’d recommend it.

Certified Copy. Smash.

Yeah… anyway, I find Showtime interesting--and a little hard to talk about because it’s so thoroughly ambiguous. I thought I’d have a more concrete list to stick to of ten or twelve questions--but…

Yeah, yeah--it’s very interesting for me, too. And that’s what I like about this, is I didn’t really… this is quite funny. The whole… your question about him not being able to communicate and stuff. It’s true.

Yeah, I actually feel like the book pushes me to ask questions that are a little more broad, or gestural.

Yeah.

I think J.1137 is a book kind of like that too. Where events don’t have a one-to-one meaning. That’s a good kind of ambiguity to have, I think.

That’s true.

But I think the way that the book is premised and sort of structured, you allow yourself a lot of room to play--there’s considerable freedom in that regard. Almost no meanings in it are precisely clear. But it still has this fairly linear backbone that creates a satisfying ending to the story.

Yeah, that’s true--and that was very deliberate. But there’s now--maybe I would have liked to have it, like--the stories are now… I’m gonna try to get them a bit more precise in the future. Like, maybe now there’s too much ambiguity to the writing. Maybe it’s too vague, I don’t know.

Because I have a very precise idea for the story--it’s like this immense journal. But it’s cool, it never really looks the way you expect it to, I guess.

Yeah, but that seems good--when the characters in the story kind of dictate their own demands. But I see why you’d want to go in the other direction, too.

Totally. That’s totally what happened.

This interview was conducted in December of 2017 and has been edited for clarity and concision. An extended preview of Showtime is available here.