Now, where did Shrimpy and Paul first show up?

Shrimpy and Paul was in Exclaim!. At first it was just random things, I think, and then it turned into mainly Shrimpy and Paul. I really started to take Shrimpy seriously at a certain point because Tom Devlin had invited me to put together a book for Highwater Books. So I simply wanted to get a book of Shrimpy stuff out and this was a way to accomplish that.

So tell me about Shrimpy and Paul. Where do they come from?

I was living in Montreal around ’95, ’96 and I drew a one off strip for a French anthology called Guillotine. Valium and Siris and Suicide and Trembles would be in it, all those guys. And ladies like Helene Brosseau. Anyway, that was the first Shrimpy and Paul strip. And then I started using Shrimpy more, and putting them into the Exclaim! strip.

Because of everything you’ve done, they’re the two kind of totemic characters. They’re like your Jimbo.

I feel like I almost like the idea of being like a one-hit wonder or something.

Did they show up in your sketchbook first?

I think I wanted to create this character…well, you use the word totemic, and I wanted to make Shrimpy primitive – weirdly primitive looking. I think I was trying to make simple characters, and I wanted to make Shrimpy simple. And I think Paul’s from looking at Betty Boop and then maybe looking at Woodring. I wanted to use some of the old-timey bits—I liked looking at Woodring, and I was like, “There’s a power in this kind of iconography” – the gloves – people recognize it. So I wanted to make characters that were recognizable, but had their own identities – the nipples thing is kind of funny. When I came up with that, I was like, “Okay, that’s funny.” And Shrimpy is just sort of trying to make a straight, simple character, which seemed to go against my usual. I was putting in effort.

You were putting in effort to construct a comic strip.

Yeah. Of course.

And did that feel like the first time you had done that?

Kind of. I kind of did, really. Well, I’m trying to think when the first strip is.

Shrimpy and Paul represents the sort of first earnest attempt at not just turning out comics about whatever, but about trying to tell stories about these two characters. Who are these characters to you? Was it just sort of a way to funnel your ideas? Were you ambitious? Were you feeling ambitious with them?

I guess I felt ambitious once I got rolling. I thought, “I want to try and make some longer stories.” For example, “The Ball, The Goose, The Power!” was me trying to sustain a narrative. So they were kind of a device to create a sustained narrative by setting them up in a situation and things unfolding from there.

That’s a lot of what your comics are: Situations in which things happen. And those situations are uniquely yours.

Yeah, and in Shrimpy and Paul, there’s always this three-quarter view of this room. I don’t know if you’ve noticed that. It’s always these things going on in these boxes, so there’s kind of a system there. Though it might seem kind of chaotic, it’s always on the same angle. You know what I’m saying?

Yeah, I do. It’s a classic comic strip device.

I like that classic thing: You always draw the door with the molding, and you draw the wood floor. Maybe that just goes back to old vaudeville-kinda comic strips; vaudeville style as opposed to cinematic style comics. I like the way Popeye looks: It’s always got that same angle, and it’s consistent that way, but maybe mine’s on kind of a three-quarter angle. I’m just trying to keep that kind of consistent look.

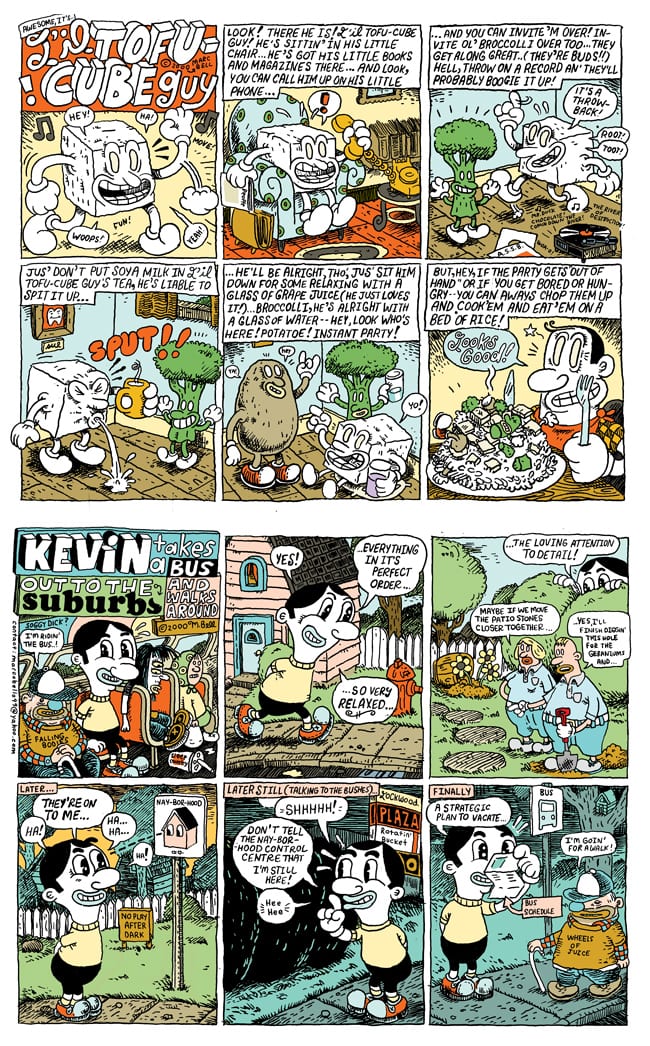

That makes sense also in the context of things like Kevin comics and Tofu Cube Guy. Those comic strip romps.

Yeah, it comes from looking at Crumb and old comics, or Betty Boop, and just trying to use the cartoon language. And a romp is a good term for those.

At a certain point with your comics, and it’s evident in Pure Pajamas, you seem to get restless with form and move away from anything too comic-like. So we get International Doodle Week as a strip, the strips in Kramers, the strips in The Ganzfeld, where you’re getting restless with the romps and the panels. What was happening there?

With the “Gustun” strip, that was maybe one of the more extreme examples, where I was trying to—and I think you were encouraging me a little bit, for me to break out of comics a little bit. And with the “Duhy Science Network” I was trying to do something a little different, and I think I was getting restless with it, and also, it’s just sort of been there, the aspect of the diagram. I’ve always kind of done cross-sections; I really like that three-quarter angle view I was talking about with Shrimpy.

But it’s also getting more internal. That’s the funny thing that starts happening. One of the reasons why I think people responded so strongly to Shrimpy and Paul was that you made characters to lead you through the world. But at a certain point you abandon characters and you’re just left with the world.

No, it’s true. I think you’re right. Those really early comics we were talking about, like Boof, they were really weird, like really kind of internal. And I think when I started doing those newspaper strips, maybe I was conscious that more people would be looking at them, that they were supposed to be entertainment. With Shrimpy and Paul, I was also conscious, at a certain point, that they were going to end up in a book. Then, later, I was getting restless and kind of going back, going back into some internalized world or something with some of the later comics. Does that make sense?

It does. And it brings us around a bit to drawing as an end in itself.

Then there was an opportunity to do an art show, and I had been doing that kind of stuff all along, really, and so I went right headlong into that area and started to spend all my time doing that. And that was a bit of a relief because I didn’t have to repeat things anymore the way you do in comics. It was wide open.

Well, the first art show is at Adam Baumgold Gallery in 2004?

It was my first real solo show. I had done two person shows with Pete and Jason, but I hadn’t really created a whole solo show. I created a small one in Vancouver at the Blinding Light!! Cinema, but Baumgold was my first real solo art show.

But all the while, long before ’04, you were making, for lack of a better term, artists’ books or drawing zines.

Yeah, I was making one-off drawings for drawing zines or “artist books” and making collaborative drawing books and mail art. Those collages I started making for the art shows evolved out of all this correspondence art that I was making. I was decorating envelopes and sending them to Jason and vice versa, and we have sent each other tons of that stuff, I was cutting out little pieces of paper and gluing them in grid-like collages on envelopes, and filling it with information. And that sort of informed those later collages. And when you put on that Ganzfeld show, instead of sending comics I decided to send that first slew of those construction things that I had made, and I think I made some new ones for that show. The whole idea of doing a show hit me at the right time, because I think I was really interested in doing that stuff some more at that time.

And these collaborations and constructions and things like that, it seems like there was a whole scene of that stuff that you were very plugged into that really was localized, and by localized, I mean just Canadian, which is a big locale.

It’s just wide. It’s wide. But it’s a small world up here.

There’s a poster you reproduced in Hot Potatoe for a drawing show, with Tommy Lacroix, Carrie Walker, Peter Thompson, Marc Bell, Amy Lockhart, Jason McLean, Owen and Terry Plummer, Holly Ward, Shayne Ehman, Dominique Pétrin, Dirty Debby, Alex Morrison. Now a bunch of those people have had significant careers on their own. So what was it about…there were comparable things going on in Providence, and the Royal Art Lodge, and probably god knows where else, San Francisco, if we think of Chris Johanson and those guys. So what was the dialogue like in this group, and what brought everyone together? Was it just that you guys were the only ones doing it, or was it a certain shared aesthetic?

I think there was a shared aesthetic. Pete and I influenced each other a lot, and our drawing sort of became seamless when we worked together because we drew together so much and influenced each other. And there was sort of a competitive quality, a healthy competitive quality, because we kind of allowed each other to rip each other off. It was encouraged. Like Pete would redraw something of mine, and Pete is a really skilled draftsman, so he draws something of mine, and it would be better or clearer, and I’d try and steal that back and redraw it again, and we’d have all these cross-references and repetitive words repeated in each other’s work and ideas. We’d joke around and come up with ideas or just jokes, and they would get into the work, and then, Pete also started redrawing some of Jason’s books. Jason would put out a book, and then Pete would redraw it and give it a different name. We also had this joke band called The All Star Schnauzer Band that we would promote. Jason really actively promoted the whole book scene in Vancouver and liked to get everybody involved. So somehow it became this little scene that either attracted people or people were yanked into whether they liked it or not, because of a shared or admired aesthetic.

Even among the artists that we talk about, the Hairy Who and Saul and Crumb and whoever, that’s a very unusual practice.

No one really did that. Jason put together a show in Vancouver called Nog A Dod, and that’s kind of where the name came from for that book I put together of all this stuff. “Nog A Dod” were just random words that had been written down in one of the zines we had made together. The poster you mentioned was for a big launch we organized. We encouraged people to make new books for it, so Tommy made a new book called Beauty of Life, I think. And everyone brought their books down and some of our friends played music. It was at Ms T’s, this tranny bar that has since burnt down. It was almost kind of folk-like. It was a localized activity, we wouldn’t make very many of these books. We’d make like forty copies. It wasn’t necessarily about selling them, it was about sending Owen Plummer your new book or trading. It sounds all so quaint. It’s kind of interesting. It was kind of an unusual thing, I guess.

Yeah. The mail art thing makes a certain amount of sense, but the copying and the obsessive trading back and forth is kind of unusual. And that’s also all drawing based, with a few exceptions, like Tommy doing the collages. What I wonder is if there an ambition behind it? Was anybody thinking, “I’m gonna do this for a little while, and then I’m going to parlay this…I want to do a gallery show, or take this somewhere it’s not.” Or was it a thing you guys did and didn’t talk about?

It’s hard to say, because there were so many different people involved. Jason and myself probably had other ambitions. Like with my comics, I was fairly ambitious, because you have to be to get them out there. I’ve never been really a reluctant artist as far as being a cartoonist, but those little minis, the drawing books, I like them as a counterpoint to that. That they’re kind of scarce. I enjoy that fact. But I still have a certain amount of ambition, and when I was asked to do a show in New York, then of course there’s some ambition there. And it’s sort of outside of that, of what was going on in that little community, because I sort of stopped collaborating. I still collaborate, but not to the degree that I did.

Well, when there’s a certain demand for your work you have to produce and can’t spend too much time collaborating, but then you lose the “do whatever I want” vibe, I guess.

And in some ways there’s a comfort to that, not worrying about having to produce, and you produce just to produce. But at the end of the day, you have to eat and stuff like that. So if you don’t want to have a job…It’s almost like I had different threads going on.

Was that confusing, having the different threads?

In some ways it was or is. I’d be working on my art in these different mediums, and I’d see what Peter’s doing, making these little black and white sixteen-paged zines, and very consistently and very prolifically, I’d be like, “Wow.” There was something to that that I felt like I was kind of missing out on. A simpler way of doing things. By doing my own solo art shows in galleries, I felt like I was missing out on this smaller scene that’s going on.

What were you getting from the smaller scene? Were you learning?

I think I learned a lot by collaborating with people. I am such a small blip in the art world, it is so hard to tell how I function in those parameters. I guess I have been learning about the business in the art world and how business is bad. Recently, I feel like I’ve just been compiling stuff and almost taking a bit of a breather rather than moving ahead. I’ve still been working, but I feel like I’m in a bit of a different phase right now. I don’t know. Collaborating could, or it probably did help me with opening the whole thing up a bit, and you’re not as precious. And the whole idea of stealing from other people can be pretty inspiring.

Oh, really?

Yeah. We would encourage it, right? It was encouraged to steal from each other’s stuff. It was kind of interesting because it would get all muddied. Pete would steal something from me and use it, and then it’s not mine anymore, which is kind of great in a way. And then I could steal it back, or I could steal something from him, and Jason’s doing the same thing, and we are sharing our iconographies a bit. In some ways it was like how jazz musicians might operate. Playing with each other, different combinations, because those guys—I don’t know much about jazz—but those guys would do that, riff on each other.

That makes sense.

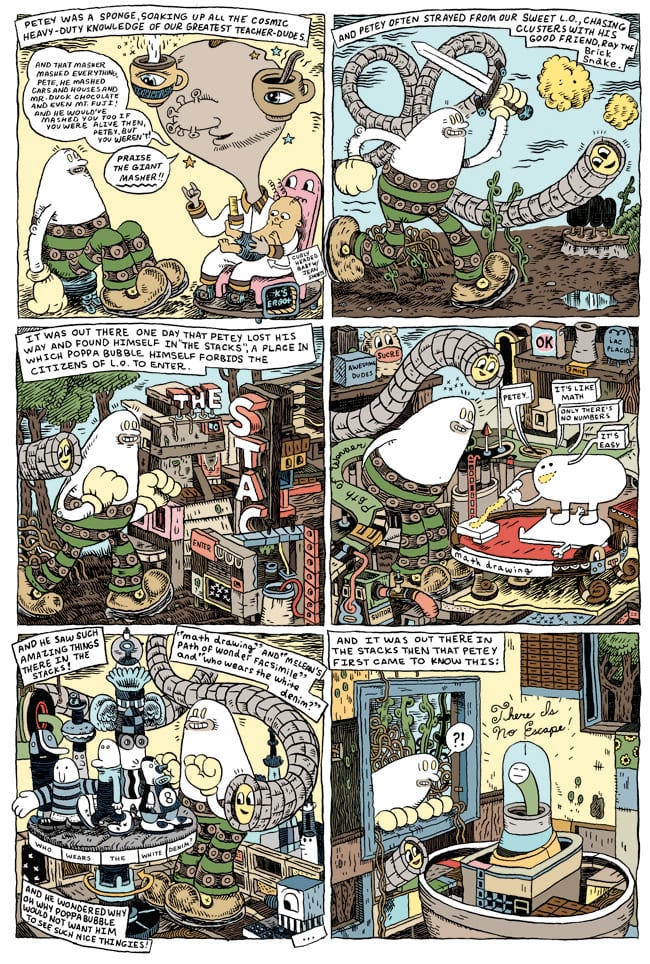

We would share terminology and characters. The strip There is No Escape! uses characters Pete and I created, those blob things. There is No Escape! in particular was a bit of an homage to the whole drawing scene, there are tons of references in there to these small drawing books by different people. And that’s Pete in there as the main character.

Actually looks like Pete a little bit.

At the time Pete’s characters would have often have a “mighty sword” and so I gave Petey one in the story.

But what gave you permission to start doing this? Because this is really starting to abandon the cartoon rules you’d stuck to with Shrimpy and Paul. It’s moving out of it. Like scenes on this third panel on page 128, so we remember for later, this is not a normal cartoon panel. You’re drawing a drawing world. You’re drawing a drawing about drawing, and then having a character run through it. What was going on there?

I don’t know. I think I like the idea of cross-referencing or something and I’d been doing these collaborative things all along. I guess I was giving myself permission to bring the “art” stuff into the comics. I felt like it was getting maybe a little out of control, because I’m cross-referencing with a bit of, I don’t want to say sarcastically, but it’s a little cheeky. I like the idea of giving things a little more importance than they might have, and then I’m bringing in the Schnauzer Band. And I am bringing The Stacks into the comics.

And you’re building up these imaginary objects. One on top of the other, on top of the other.

It’s kind of like piling stuff up. And then in the background here (in There Is No Escape!), there’s Brosse the Goose from Shrimpy and Paul. I think I told this story somewhere already about the origin of Brosse—but this crazy woman was talking to us in Oppenheimer Park in Vancouver, and saying, “Do you know who Brosse is? He’s the goose. Do you know what that means? That means he’s greedy.” And I thought, Brosse the Goose…that’s interesting. I had this really crusty blue wood board that I liked, and with Liquid Paper I just drew this goose, or a bird on it, and I decided that was Brosse the Greedy Goose and I just took that and brought that into the Shrimpy narrative.

Did you worry when you were doing these sort of comics, though, that you weren’t telling stories anymore?

Oh, yeah. For sure.

[Laughs.] But it didn’t stop you.

Didn’t stop me.

In a sense, you were taking all these pieces and, in a sense, drawing what you might otherwise collage.

I’m drawing collages. But when you first glance at them, they do look like regular comics sort of, but then you get into, and it’s just all stacked up.

Were they satisfying to make?

Umm…I’m proud of the drawing in this one.

I think the drawing’s fantastic.

I really like the drawing in this one; I like the coloring. That was when I trying to figure out how to color on the computer, and maybe I read something Jordan Crane wrote—I’m not sure if it was Jordan Crane—and they said to use the brush tool. Maybe I read it wrong, I don’t know, but I was literally coloring these pages with just the brush tool and not the magic wand where you just select areas. And it was crazy. One of these pages would take me sixteen hours or eighteen hours. It was so stupid. I could have done it in probably two hours the way I work now. So I gave myself carpal tunnel.

Doing the strip?

Yeah. Coloring it. At the time I had a deadline for one of my song comics. I think it was Mick Jagger’s “Let’s Work” For Vice. That awful song. And Tom Devlin colored it for me. I couldn’t because my hand was fucked up.

Do you feel like your comics became about this world that you built up? It’s interesting. You clearly, over time, have built up this visual and linguistic world, but then you’re exploring it.

But some ways, in the back of my mind, I would think, “I’m not making it concrete enough.” I would think, “Maybe I’d like to do something that really makes it more permanent.” Like, should I make a map of this place? I was thinking about going further with it and really trying to stabilize it or something. I’d introduced so much that I thought I should just double back and go through the stuff and really try to expand upon it. Rather than just making more stuff, rather than just making more components, which is unfortunately what I was doing, I think.

That’s your tendency.

That’s my tendency. I don’t know, I guess I just do what I do. I probably have to make a real serious, conscious effort to control it more or something, to pare it down. Does that make sense?

It makes perfect sense. And so, Pure Pajamas… It’s an interesting book, because it does present a real cross-section of everything. We get a little bit of Shrimpy and Paul...

In some ways, it was kind of too bad that I’d put those comics in Hot Potatoe, because those could be in Pure Pajamas. But the reason I put those in Hot Potatoe is because they kind of referenced the art a little more. So these are more of the supposed entertaining comics, maybe. The “romp” comics, as you say.

And what was the reaction to these comics? We’re in 2000, 2001, 2003, and you’ve got the weekly strips and Exclaim. What was the response to the sort of entertaining comics of the early 2000s?

The response to the so-called entertaining comics…It’s funny you call them entertaining, because some people are just like, “What, I do not…” And the other thing is, when I was putting stuff in weeklies and monthlies, often I was trying to get work done, so I could put it in a book later. For example, when Shrimpy was appearing, and I knew Tom Devlin was gonna put out the book, I was trying to get as much done as possible, and I was cramming, like, nine panels in this tiny space, and people could barely read them, I think. So probably some of the response would be just annoyance, I think. But I was just trying to get the work done. My space in the paper had gone from half a page to one quarter of a page and I still was determined to get the same amount of work done. And in a way, it paid off, because I got the book done, I got the Shrimpy and Paul book done. But sometimes I’m not thinking enough of the audience. I just have something else on my mind.

What do you have on your mind?

I was just thinking that I wanted to get the book done. But people were fairly positive about Shrimpy, and people did respond to the Vice song comics, and people responded to a lot of these ones. These ones were in Vice.

(Continued)