Bruce Berry is best known as Jack Kirby’s controversial inker, who took over from Mike Royer during Kirby’s ‘70s run at DC. Perhaps Berry suffers in his close proximity to Royer, Kirby’s most faithful and therefore considered by many, his best inker. Conventional wisdom is that Berry worked for decades as an advertising product/mechanical artist before Kirby brought him on board, thus beginning his comics career.

Truth be told, Berry was an often-published pulp and fanzine illustrator, science fiction author and novelist, dating back to the 1940s. He was also a brought to court for threatening others in the science fiction community and had been confined to a mental institution as a result.

Douglas Bruce Berry was born on January 24, 1924 in Oakland, California. During World War II he served in the United States Army Air Force. Following the war, he began submitting illustrations to various science fiction pulps and fanzines. Self-taught, his earliest influences were the 1930s Flash Gordon comic strip by Alex Raymond and later the pulp illustrations of Virgil Finlay.

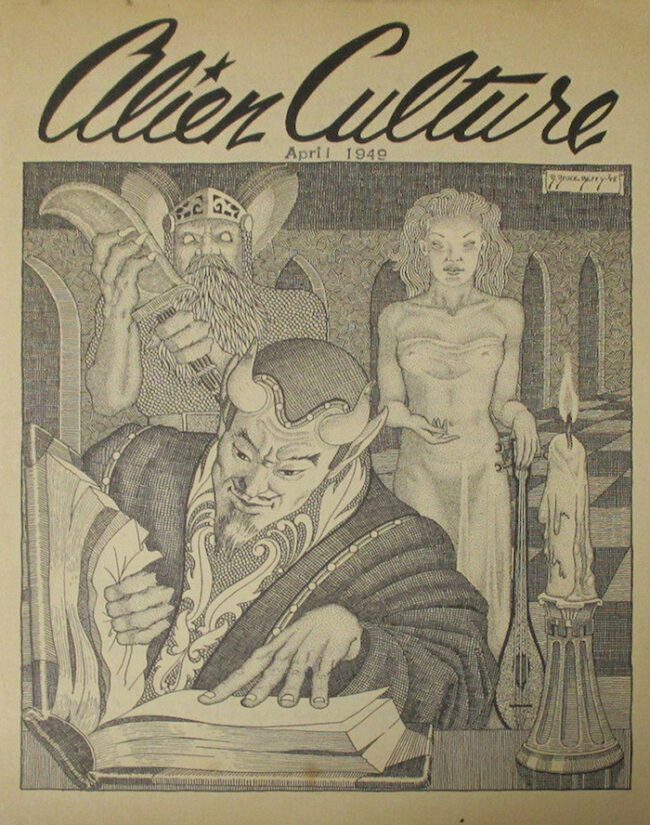

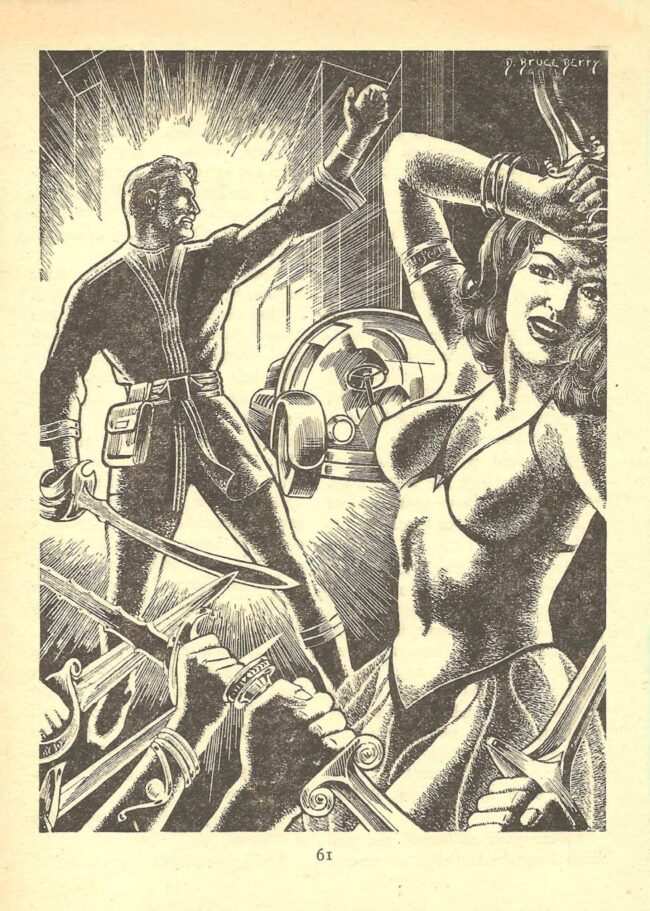

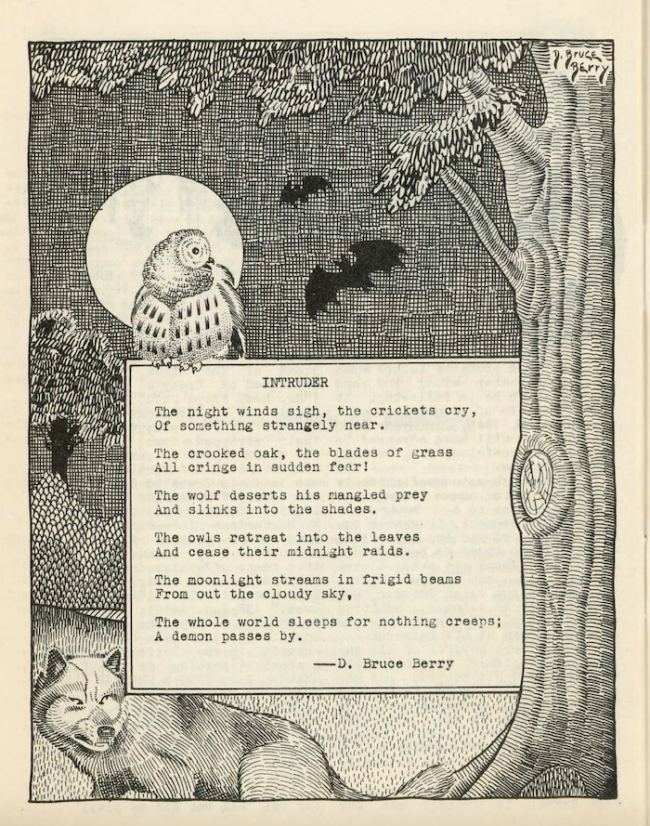

Seeking science fiction reading material at an Oakland bookstore, he met book store clerk Richard Kyle, future comic book critic and historian and publisher of the newsletter Graphic Story World, who introduced him to science fiction and comic book fandom. (1) Berry’s work was soon in print, and in the 1948 Fantasy Annual, published by Forrest J Ackerman, Berry was ranked 3rd in the list of Top Fan Artists. Berry’s cover and interior art appeared regularly in The Fanscient beginning in 1948, and his work shortly thereafter was published in William Hamling's Greenleaf Magazines: Imagination, Imaginative Tales, and Space Travel, as well as Other Worlds, Men’s Digest, Rogue, and Witchcraft & Sorcery for various publishers. In 1949 he was one of ten winners of a contest held by the Portland Fantasy Society to illustrate “The Final War” by David H. Keller, a short story, published by Perri Press.

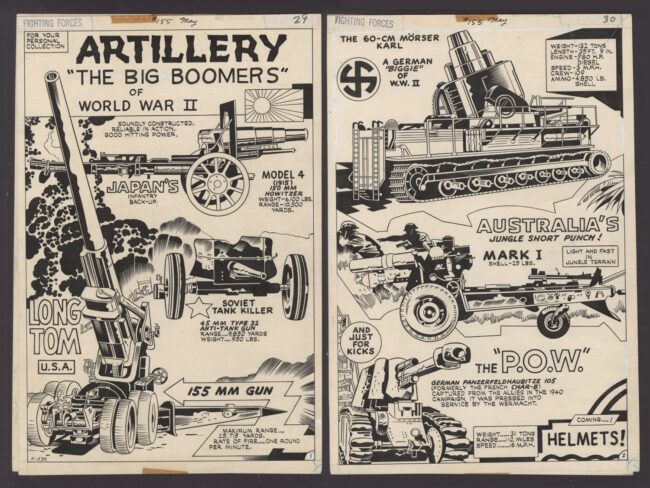

Berry also began working in advertising as a merchandise artist, drawing machinery, jewelry, pots and pans, a position he held for almost 30 years. In the 1950s he moved to Chicago, where he continued his work in advertising.

Things took a strange turn in 1958 when Berry began sending a series of bizarre and threatening letters to Chicago based science fiction editor and critic Earl Kemp, who had also worked for Hamling’s Greenleaf Magazines and knew Berry in passing. The letters continued and Kemp’s wife and children were threatened as well, prompting Kemp to seek legal counsel. Berry was brought to court in June 1959 to stand trial for disturbing the peace, with the letters as evidence. The judge declared, “The letters are clearly life threatening to Mr. Kemp and his family” and directed that Berry be taken in for mental observation. The doctors concluded that he required treatment and he was confined to a mental institution. Berry was discharged in August 1960. (2)

It didn’t end there. Two years later this culminated in a 38-page rant entitled A Trip To Hell, written by Berry and published by Robert Jennings, editor of the fanzine Comic World. In his introduction, Jennings wrote,

“There has been quite a bit of discussion in fandom lately about the persons who exhibit undesirable characteristics. The discussion has been continually marked with cries from people who would like for names to be named, and facts to be pointed out clearly for all to see. A TRIP TO HELL names a name or two. In the time I’ve corresponded with Bruce Berry, I’ve never known him to tell a deliberate lie, nor to shield the truth in any way. He has sent me enough documentary evidence to convince me beyond a doubt that his story is true.” (3)

In the essay Berry claimed Kemp and science fiction editor and writer Harlan Ellison, wearing masks, had held him up at gunpoint on a Chicago street on Labor Day night, 1958. From Berry’s treatise:

“Hold it, mister,” he said, “Hold it right there.” He was pointing the sleeve at me and I could see the barrel of a gun sticking out of it…. I heard the doors of the parked car opening and heard the sound of running feet. A little guy came running around from the other side of the car and came up to the sidewalk. Another taller man ran from the driver’s side of the car and stopped on the sidewalk about 20 feet from me. He was facing me and the light from the front of the apartment house fell on his face. “Good God!” I thought. “It’s Earl Kemp!” There was no doubt about it!!” (4)

One problem with this scenario is that at the time of the alleged attack Kemp was two thousand miles away attending the Worldcon in Los Angeles, presenting to several hundred science fiction fans. (5) Even stranger is that while at first Berry identifies the second attacker as Harlan Ellison, whom the first addressed as “Harl,” he goes on to state that this was actually an Ellison lookalike Kemp hired to discredit Ellison. Berry also believed Kemp “railroaded” him into the asylum. (6)

Jennings released this libelous tome at Chi-Con III, which Kemp chaired, and Kemp viewed this as an attempt to usurp his role and take over the con. Kemp released a statement, “I feel obligated to remind everyone that there is not one word of truth in Berry’s 38-page diatribe directed at me and at Harlan Ellison. I also feel obligated to remind everyone that Berry chose to ignore all of the things that led up to his much needed trip in his narrative.” (7) Jennings effort to discredit Kemp failed and he was duly ostracized within the science fiction community.

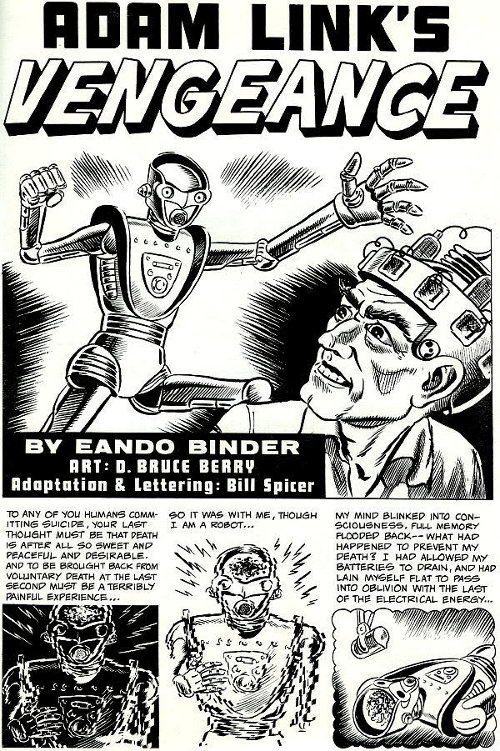

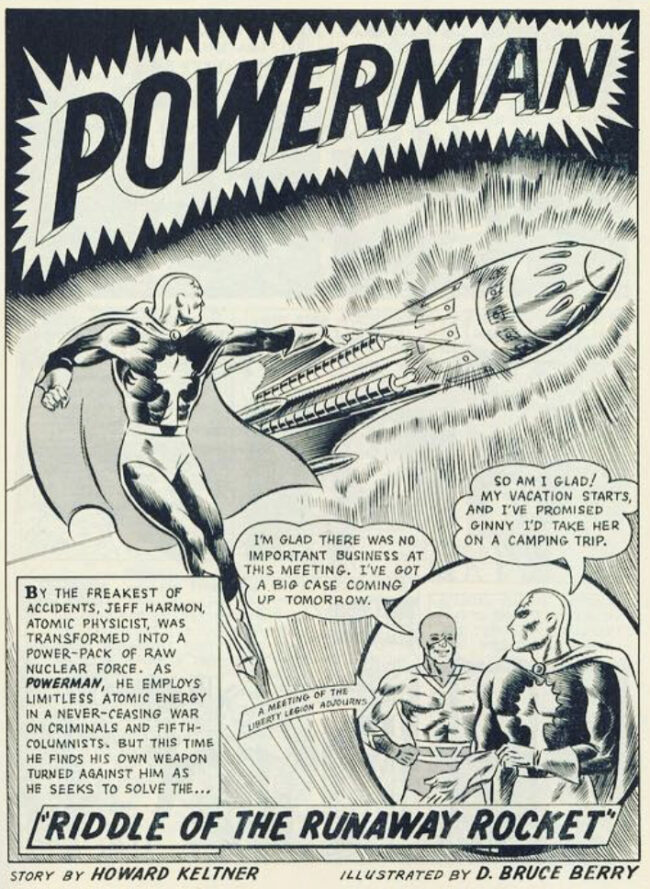

lettering by D. Bruce Berry

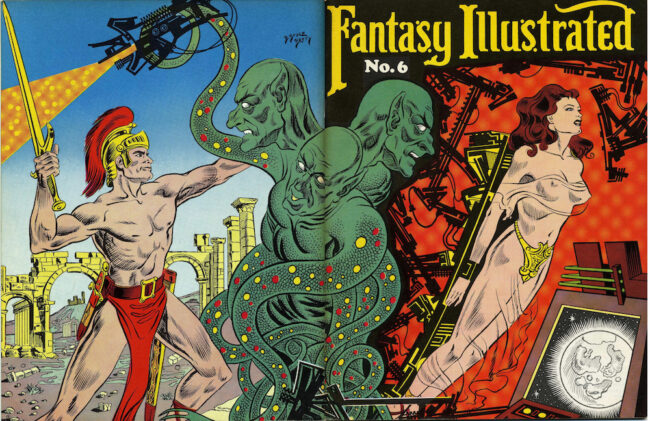

Berry, however, bounced back fairly quickly. The following year, in 1963, he began a working relationship with publisher Bill Spicer, with his work appearing regularly in Fantasy Illustrated alongside such illustration pros as Wally Wood, Al Williamson, Russ Manning, Jeff Jones and Dan Adkins. This included Berry’s first sequential comics art, an adaptation of Eando Binder's 1940s pulp novella “Adam Link’s Vengeance”, which won the Best Fan Comic Strip award in the 1964 Alley Award.

Returning to the comic form, Berry penciled, inked and lettered the cover and six page story, “Riddle of the Runaway Rocket!” featuring Powerman for Star Studded Comics, a fan produced comic book in 1965.

In 1970 Berry wrote the first of three novels, the pornographic Flowers of Hell under the nom de plume Morgan Drake. The following year he co-authored, The Balling Machine with Andrew J. Offutt, a science fiction, fantasy and erotica author, collectively as Jeff Douglas; and again in 1975 with Offutt a science fiction erotica novel, The Genetic Bomb, this time using their real names, published by Warner Books.

To say the latter is overwrought is an understatement. It begins, “Shrieking madness lurched across the airless waste, crying out to the stars that burned coldly, disdainfully: “No! Damn it no! I’m a MAN! It can’t happen!” and doesn’t let up for the next 207 pages. (8) Combine that with the misogynist adolescent fantasy plot of “Beautiful girls going mad—writhing in pain and ecstasy as they live through hallucinations of a world-consuming conflagration and a final orgasmic farewell to life” (9) and you have a book that is essentially unreadable.

Advertising work having dried up in Chicago, Berry relocated to Southern California in the late 1960s. Richard Kyle helped set him up in an apartment and introduced him to professional cartoonists working in the area, which included Mike Royer. Royer had recently begun inking and lettering Jack Kirby’s “Fourth World” series of comics for DC and soon afterward he employed Berry to ink backgrounds to help keep up with the voluminous flow of work. Berry took over the full inking and lettering chores with Kamandi #17 in 1974 and remained as Kirby’s inker for most of the rest of his DC run. According to Berry, “Mike said to me, “You won’t have any problems. Just follow the lines.” Keep in mind I came out of the advertising business. When an art director tells you the way a thing should be done, it’s the rule of the game. Mike said, “follow the lines,” and that is exactly what I did.” (10) Trying to remain faithful to Kirby’s pencils as Royer had been, Berry approached the inks like a schematic, using mechanical pens and tools, which produced a static even line width (unlike Royer who employed brushes for a robust result.) The end result was that he broke Jack's pencils into shapes and patterns, an earmark of product illustration, to mixed effect. Oddly, none of these techniques are evidenced in Berry’s own artwork. During this period Berry also worked occasionally in Kyle’s Graphic Story Bookshop in Long Beach (11)

He followed Kirby back to Marvel in 1975, working primarily on Captain America, but the company wanted to use only local New York artists and Berry had no desire to relocate. In 1978 he worked for Marvel’s Hanna-Barbera comics coloring and lettering and in 1983 he reunited with Kirby on Silver Star for Pacific Comics and also illustrated backup stories written by Kyle, featuring Detective Flynn.

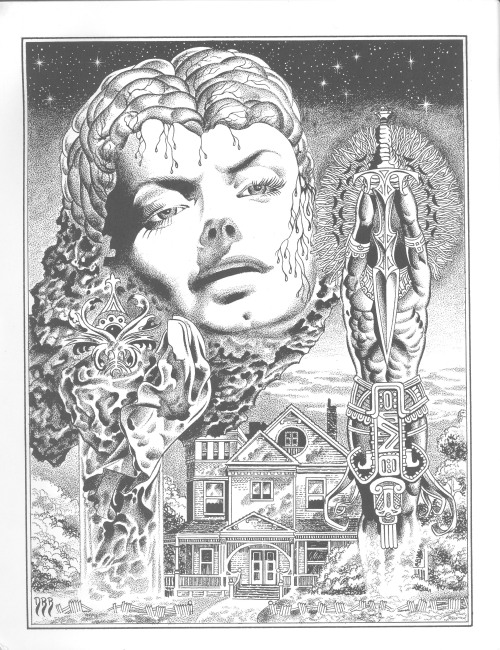

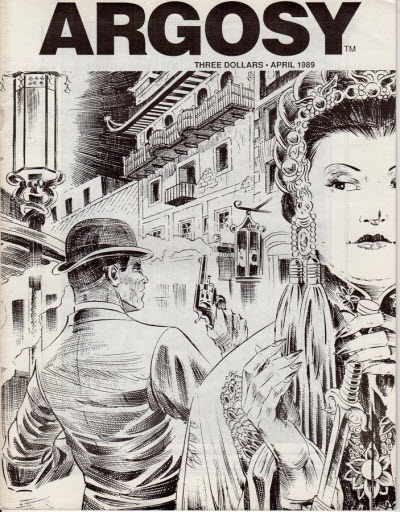

In 1984 he worked again with Kirby for a final New Gods story, “Even Gods Must Die!” that concluded a reprint series and also on the follow up graphic novel The Hunger Dogs. This was to be Berry’s last comics work. He illustrated a cover and a few stories for Argosy in the late 1980s, written by Kyle. His final professional work was for an educational publisher out of Carson, California and then he retired, losing all contact with science fiction and comics fans and pros alike. He was briefly interviewed only once, by John Morrow for The Jack Kirby Collector in 1997 and at the time was unaware that Kirby had passed three years prior. (12) Berry died on September 30, 1998 at age 74 in Long Beach, California. His art is in the permanent library collection of Harvard University.

Works Cited

- John Morrow interview with D. Bruce Berry, “D. Bruce Berry Speaks,” The Jack Kirby Collector #17, 1997

- Earl Kemp, Harl 'n Neverland* Visions of Another Dimension Through a Mind Darkly

- From the introduction to A Trip To Hell, written and published by Robert Jennings, 1962

- A Trip To Hell, written by D. Bruce Berry, and published by Robert Jennings, 1962

- Robert Coulson, Yandro 115, Vol. X, No. 8, August 1962

- Richard Lynch, Preliminary Outline For A Fan History of the 1960s, Chapter Five - publications and legendary, Fanzines, fan publications, and fannish pastimes

- Earl Kemp, Harl 'n Neverland* Visions of Another Dimension Through a Mind Darkly

- “The Genetic Bomb” by D. Bruce Berry and Andrew J. Offutt, Warner Books, 1975

- Back cover blurb, “The Genetic Bomb” by D. Bruce Berry and Andrew J. Offutt, Warner Books, 1975

- The Jack Kirby Collector #17, 1997

- Mark Evanier, “News From Me” blog, https://www.newsfromme.com/?s=d.+bruce+berry

- The Jack Kirby Collector #17, 1997