What is so special about this manga? In a brief published to accompany the black and white reprint of Clover in the magazine Tsumugu, Natsume Fusanosuke writes the following: “I had no idea that there existed manga with such a scintillating illusion of perspectival space. . . There are bodies with actual joints and proper proportion moving about in all directions within a landscape of exaggerated spatial depth. Compared with Norakuro and Speed Tarō, it all feels much closer to postwar manga.” I will deal with such formal issues in the next chapter of this series.

The other common observation is that Clover is an early entry in that staple shōjo genre: the historical European costume drama. In his thorough study of Tezuka Osamu’s shōjo work, The Representational System of Shōjo Manga (Shōjo manga no hyōgen kikō, 2013), Iwashita Hōsei points out that not only were there gender-bending European medieval dramas within emonogatari and illustrated juvenile fiction in the years just prior to Princess Knight (Ribon no kishi, 1953-56), but seemingly related stories of girl heroes in male samurai gear date back at least to the late 1920s. How does Clover compare with these? What was distinctive about its masquerade? I have not read them to answer.

Let me instead offer a rough reading of Clover through what I take to be one of its Hollywood sources. The Disney factor will be explored in the last installment of this series. But underwriting the Disney factor was a live action star, in fact one of Mickey Mouse’s inspirations: Douglas Fairbanks Sr. Given that Matsumoto is celebrated for introducing a new shōjo type through his illustration work – which predates his manga work – I think it makes sense to first ask about Clover’s character before analyzing the attributes of the manga’s composition and breakdowns. Her character, after all, is more Fairbanksian than Disney-esque.

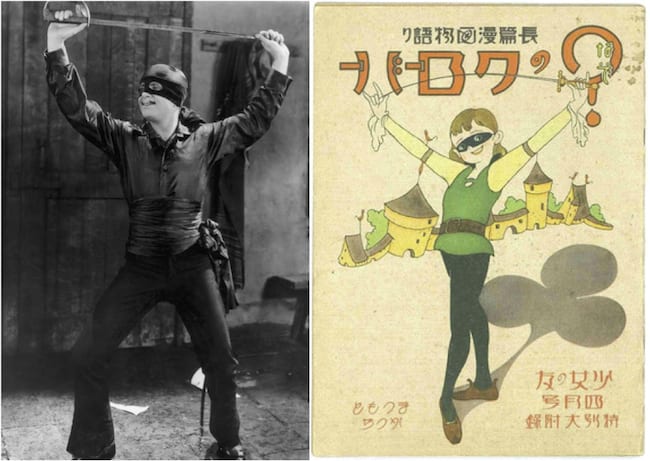

It is sometimes said that Clover was inspired by Zorro and the Scarlet Pimpernel. Matt Thorn has stated this on his Wikipedia entry for Matsumoto, with no specification of whose Zorro or whose Scarlet Pimpernel. For me, these associations only make sense from a limited point of view. The most Zorro has in common with Clover is the rapier and the mask. But even the mask is wrong, for Clover’s just covers her eyes while Zorro’s is a scarf that wraps over his head. Zorro does fight against corrupt and oppressive officials, but he is not a robber prince of the poor like Clover. Zorro is a nobleman, while the shepherdess Clover is of lowly birth. Zorro lives in Spanish California; Clover’s stomping ground is medieval Europe. As for the Scarlet Pimpernel, I fail to see any real connection. The costumes are off by a couple of centuries, and the Pimpernel fights for the wrong side, for the Ancien Régime.

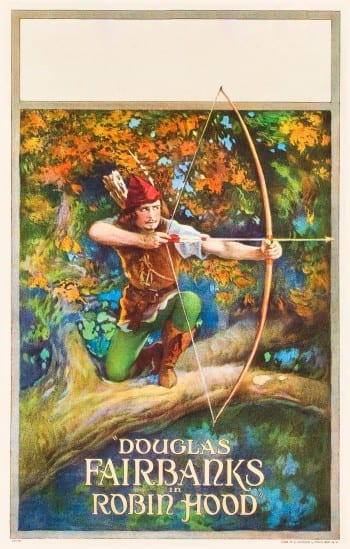

The Mysterious Clover is obviously a Robin Hood story. The manga’s cover is a give-away. Clover might wear black and a cape in the story, but here she wears tights and a Lincoln green tunic, and who else could that be? Of course, Clover wields a sword whereas Robin was famed for his bow (more on that below). Most importantly, the robber prince has been turned into a girl. But other core elements are there: the exploited villagers, the deposed good king, the masked hero, the redistributed wealth, the merry gang, and the medieval European setting – which I think some readers assume to be French, but considering the setting of the Robin Hood myth is better described as a liberal rendition of Norman English.

Clover’s origin as a lowly shepherdess is interesting. First it means that Matsumoto consciously chose not to identify with the “gentrified” Robin – Robin Hood as Lord Locksley or Earl of Huntingdon – that dominated book and film versions at the time. Like Floyd Gottfredson in the Mickey Mouse color Sunday strip “Robin Hood Rides Again” (1936), Matsumoto is returning Robin to something like his popular medieval roots (on what model, if any, I do not know). Lest you think this is a radical Robin, don’t forget that Clover fights for the restoration of the monarchy, in the spirit of Robin’s allegiance to good King Richard. Matsumoto was not populist enough to take the Geoffrey Trease path, who in the very same year (1934), with his Bows Against the Barons, remade the outlaw woodsman myth as children’s proletarian literature.

Perhaps Matsumoto’s motivation to make Robin plebian is a consequence of the primary need to make him a her. Kurumi chan merchandise suggests that the artist knew Little Bo Peep. Was he aware of Maid Marian’s pastoral roots, the fact that Marian was introduced into Robin’s world as a shepherdess centuries before being elevated to Saxon noblewoman or Norman princess? Though they presumably have no direct relation to The Mysterious Clover, there were English precedents for a cross-dressing Marian: books, ballads, and plays in the 18th and 19th centuries in which Marian slips into tights and arms herself with a bow. Perhaps Matsumoto avoided making Clover a radicalized princess simply to ensure that Clover’s moral example would be effective amongst his middle-class girl readership. Perhaps, as I propose below, it was because Clover was responding to images of progressive femininity from the 20s and early 30s (the American flapper and the Japanese moga, as well as the upbeat and go-get-‘em girls’ school student) that it was essential not to make her aristocratic. Given the melancholic and pastoral first panels, perhaps this was Matsumoto demonstrating that even the waifish girls of jojōga illustration could be shaken into action.

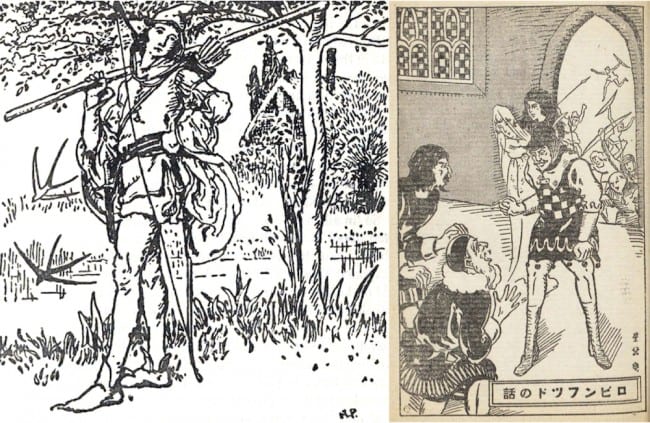

The manga’s cover is suggestive. It does not offer clues as to why the gentrified Robin and Marian were avoided. But it hints at why it was easy for Matsumoto to imagine Robin as lithe and potentially feminine, despite the fact that the woodsman in the most popular modern books (those illustrated by Howard Pyle, N.C. Wyeth, and Walter Crane) was depicted as relatively stout (but not always, especially not in his youth). Here the detail of the sword is telling. Though famed as an archer, Robin was able with a sword, as we know from his initial encounter with Friar Tuck and his slaying of Guy of Gisborne. But in both case he fights with a broadsword, whereas Clover sports a rapier. As Matt Thorn notes, Zorro is a possibility. But there is also the rapier of d’Artagnan from The Three Musketeers.

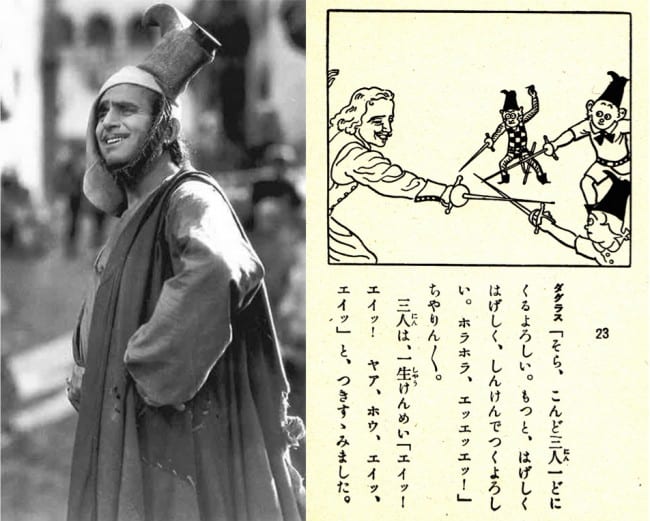

What is the common denominator here other than European romance and swashbuckling? I have already given it away: Robin Hood, Zorro, and d’Artagnan were all played by Douglas Fairbanks Sr. in some of Hollywood’s most spectacular and popular productions of the 1920s: The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), Robin Hood (1922), The Iron Mask (1929). Before animation characters like Mickey Mouse, Betty Boop, and Popeye infiltrated manga, the appearance of actual Hollywood actors was not uncommon. There are a few manga from the 20s and early 30s with Roscoe Arbuckle, Harold Lloyd, and Buster Keaton, and a few more with Chaplin. Fairbanks, meanwhile, cameos in a famous emonogatari from Shōnen Club: Makino Taisei and Imoto Suimei’s The Three Musketeers of the Long Boots (Nagagutsu no sanjūshi, 1929-31).

In The Mickey Method (Mikki no shoshiki, 2013), Ōtsuka Eiji praises Three Musketeers of the Long Boots for its novel interpretation of the emonogatari format in terms of silent cinema, in which portions of text are referred to as “titles,” chapter endings as “fadeouts,” and the work itself as a “moving picture manga” (katsudō shashin manga). Its affiliation with the silver screen did not stop there. Not only do the starring triumvirate – a boy, a girl, and a monkey – receive instruction in swashbuckling from Fairbanks himself. But their unique curse of having boots stuck to their heads was presumably inspired by the queer headgear Fairbanks wears as Petruchio during the wedding scene in The Taming of the Shrew, which was released the very year (1929) that Three Musketeers of the Long Boots commenced.

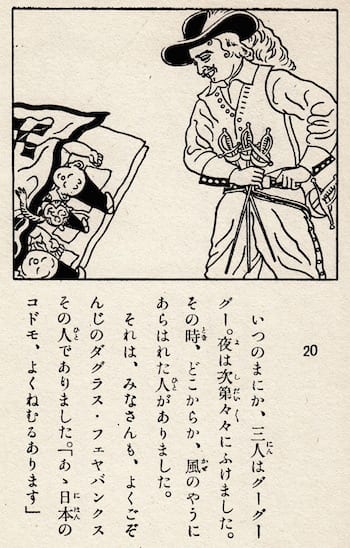

Note the nonchalance with which Fairbanks enters the story. “Before you knew it, our three friends started going ZZZ ZZZ ZZZ. The night grew deeper. It was then that, from out of nowhere, as if riding on the wind, appeared a man. That man was none other than Douglas Fairbanks, whom all of you know so well. ‘Hey, children of Japan, you sleep good.’” (The bad English grammar here is meant to capture the American’s poor Japanese grammar in the original.)

“Yes everyone, up up,” announces Fairbanks, dressed as d’Artagnan. “Yes, hang this sword from belt good. Me swordfighting, teach you, everyone get strong.” And without a bat of the eye the three respond, “Splendid, how fun.” Apparently Fairbanks was so familiar to Japanese children to evoke no surprise from the characters, and require no introduction to readers.

A “title card” text informs us that Fairbanks came every night to teach the three friends fencing. His first lesson: “Spread your legs like this. Raise your left arm like this. Point your sword straight forward like this, aiming for your enemy’s heart, like that good. Practice hard good. Ya! Ya! . . . Now all three of you let’s go good. More, harder, harder, swing hard good. Hey hey! Ya ya ya!” And as their rapiers clang together with a “charin charin,” the heroes cry out, “Hiya! Hiya! Ya! Ho! Hiya! Hiya!”

Then one night Fairbanks bids his students farewell. “Everyone studied hard, skill improve greatly. Put your three hearts together, become three musketeers good. Nothing to fear in the world. Farewell, I return to America.” And thus “Doug” – the Japanese uses the familiar truncated first name – disappears. Back to America, note, not France.

Makino and Imoto’s Fairbanks is not exactly the athletic dynamo of Hollywood fame. The Doug character is in proper action costume and energetically yells out the proper action cues. Yet he is more avuncular than brotherly in his looks and demeanor. This is not the gamboling d’Artagnan of The Three Musketeers (1921), but the aging swordsman of The Iron Mask (1929), Fairbanks’ last historical drama. An aging swordsman, silent film inter-titles, the simple line-work typical of comical manga emonogatari of the 20s (sometimes called manga manbun at the time): The Three Long Boots Musketeers marks the end of an era in entertainment in more ways than one.

Yet this was not finis for Fairbanks in Japan.

(cont'd)