This interview ran in The Comics Journal #122 (June 1988)

* * *

2022 NOTE: Frank Plowright co-edited the 1988 British Comics Scene issue of The Comics Journal. He spoke to Judge Dredd co-creator John Wagner and Alan Grant, the former's close collaborator throughout the 1980s and a prolific creator and scripter in his own right. When contacted for permission to rerun this interview, Plowright requested this update:

“The interviewer has subsequently learned that keeping a roof over his head and food on the table requires earning money, and that working ten hour days without enough of it can cause problems.”

* * *

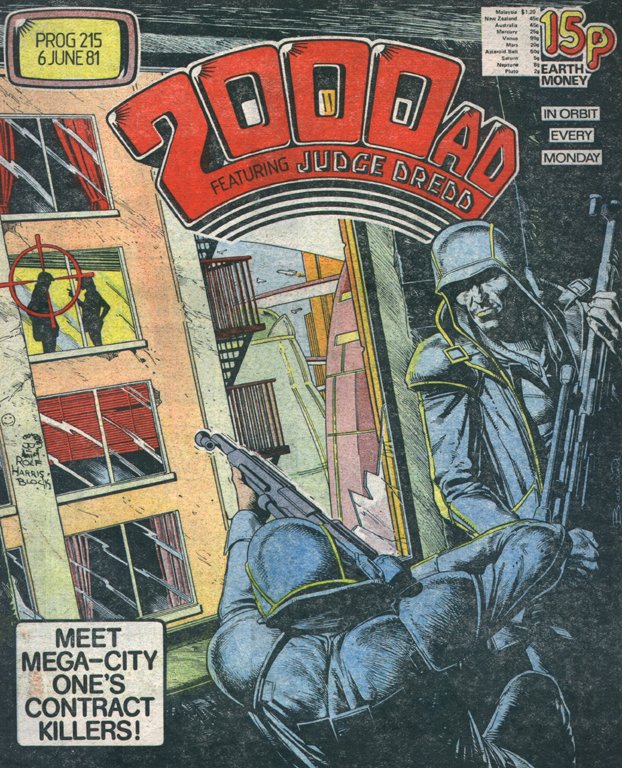

Judge Dredd is 2000 AD, 2000 AD is British comics in the ’80s, so John Wagner and Alan Grant are British comics in the ’80s. Q.E.D.

In this forthright discussion, Wagner and Grant define their politics and those of their controversial creation, compare Dredd artists, and talk about coping with the seemingly random taboos of British and IPC censorship.

—Frank Plowright

*All comics images written by John Wagner and Alan Grant unless otherwise noted.

* * *

FRANK PLOWRIGHT: We’ll start by talking about Judge Dredd, which comprises the bulk of your best-known work. John created the character and you’ve been writing the strip together now for about five years.

ALAN GRANT: Longer than that. Six years.

JOHN WAGNER: Nearly seven. It’s a long time. We must have written nearly 600 Dredds.

PLOWRIGHT: It’s astounding that you don’t repeat yourselves.

WAGNER: Well, actually we were in the middle of a story the other day when we realized that we’d already written it, or segments of it, so we had to go back and change them. “You’ve winced at Megaman, now groan at Fairly Super-Man.”

Megaman was your superhero in Mega-City One.

WAGNER: Fairly-Super-Man is more interesting.

GRANT: He’s a genuine super-hero. He’s got fairly real super-powers. He came from a fairly dense planet with a fairly red sun and he’s got fairly hot vision and fairly cold vision.

WAGNER: Fairly super breath.

GRANT: He announces to Dredd that the judges are now redundant and he’s taking over as protector of Mega-City One.

How did Judge Dredd come about? I know you were given the name by Pat Mills.

WAGNER: I don’t really want to dwell on that. I’ve told the story so many times I’m a bit sick of it.

It means that you’ll have it down pat.

WAGNER: Pat Mills was creating 2000 AD I’d been editing Valiant a short while before that and had produced a new story for it called “One-Eyed Jack,” who was a Clint Eastwood-type of cop, tough and violent. The popularity of that story was amazing, so I knew that tough, violent cops worked and suggested the idea for 2000 AD But in the future the character could have far more power. He’d be Judge, Jury, and Executioner. The original Judge Dredd was a far more violent character, a man who would kill you for jaywalking. In the first script that I wrote there was a scene in which there’s a siege or something. Dredd rides up to deal with it and a citizen leaps out into the road and says, “Here comes Judge Dredd, he’ll sort them out!” Instead, Dredd runs the guy down with his motorcycle and says, “You were jaywalking, creep. Tell you what, I’ll be merciful—you’ve got five seconds to make the pavement.” The guy’s crawling along but he doesn’t make it. So Dredd says, “Sorry, too late,” shoots him and rides on. Originally he was a total maniac, and IPC, probably wisely, decided that this wasn’t on.

That would have been about the time that Action had been pulled for being too violent. It’s what the kiddies love, though, violence.

WAGNER: They like a good strong character, and you can’t get much stronger than a homicidal maniac. An upright, righteous, homicidal maniac.

Would I be right in saying that the way you both look at Dredd is that he’s not to be taken seriously in any respect?

WAGNER: I wouldn’t know how to answer that.

It seems to me that the character of Dredd is misinterpreted. There’s the story about the letter from a Democrat which ends with a wonderful quote from Dredd: “Democracy’s not for the people, citizen”—it’s the type of thing that people seem to take at face value, they see Dredd as a straight character.

WAGNER: You mean that they believe that he’s the one that in the right?

GRANT: In a lot of cases that’s true.

WAGNER: The story you mention there is one that we wrote to set the record straight, to show what a bastard Dredd really is. That people should come out of that thinking that he’s the good guy surprises me. There’s a follow-up to that story in which he’s even heavier and even more unpleasant.

Speaking to friends in the USA, they say that Dredd is taken at face value.

WAGNER: That is why we do quite frequently run stories showing him in a bad light.

GRANT: “Letter from a Democrat” originally started off as a deliberate attempt to make Dredd look bad, it didn’t have anything to do with democracy. At first it was just a stupid terrorist group, the Baffin Island Nudist Liberation Front or something, but we couldn’t find anything that satisfied us until we went through the Guardian and found a big piece on the Militant Tendency. Adapted to the Mega-City it became the Democratic Tendency—the perfect name.

WAGNER: We wanted to leave the reader with a bad taste in his mouth about Dredd, and make him wonder if all the other things Dredd has been doing are right. Obviously it didn’t work.

That story’s never been mentioned in the context I brought up, I just used it as an example because of that quote. It worked that way for me.

WAGNER: A similar story was “The Man Who Knew Too Much” about the guy who discovered the Judges were tranquilizing the whole city.

GRANT: And no one seemed to care about that story. We thought we’d get an avalanche of letters from people saying how terrible it was.

WAGNER: We wonder if our readers are more right-wing than we are.

Do you consider yourselves right-wing?

GRANT: I think we’re right-wing with left-wing tendencies. We both subscribe to Greenpeace.

Flared-trouser men, really.

GRANT: Oh, I still have a pair of flared trousers somewhere.

Do you worry about the way people might interpret what you write?

GRANT: When we started working together it used to worry me an awful lot. We used to have severe lengthy arguments about whether what we were writing was the correct thing to be presenting to kids for reading material. Mixing up humor and violence the way that we do. the two become indistinguishable. So we wrote a story that was supposed to leave a bad taste in the mouth and it didn’t work.

WAGNER: Because of that one line. Still, we like to keep Dredd coming out with his one-liners. They often seem to sum up the city.

Are they something you can string a story around?

GRANT: Quite often Dredd’s final line justifies the entire story and it wouldn’t be worth printing were it not for Dredd’s wisecrack at the end. I can’t think of any examples offhand.

WAGNER: There’s one that always comes to mind—Judge Minty’s quote.

This was the Judge who took the long walk out of the city into the Cursed Earth?

WAGNER: Yes. It went something like “When you get old you start having strange notions—like maybe people aren’t so bad, maybe if we treated them with kindness the good in them would come out ...I guess that’s when it’s time to quit.” That’s the city in a nutshell.

Dredd is a very oppressive strip. No one gets away with anything. The only person I can remember getting away with anything was the guy who was mental.

GRANT: We don’t often let criminals escape. It’s on the understanding that if they break the law they’ve got to pay the price.

WAGNER: Another reason is that it’s the only way we can get Dredd into a story sometimes, to have him come along at the end and make the bust. We’d often prefer to leave him out and do stories about the city, but when we do, Steve [MacManus, editor of 2000 AD] says that it won’t do.

He demands that even though it’s a good story? There have been so many spin-offs from Dredd you’d think there would be enough license for you to do these stories.

GRANT: We would think so.

WAGNER: We would like to be free to leave out Dredd, but they put “featuring Judge Dredd” on the cover so we’ve got to stick him in the story some place.

GRANT: We had a Judge Dredd story rejected a couple of months ago. It’s the first one that’s been rejected in ten years of John writing Judge Dredd.

WAGNER: I wouldn’t say it was the first one.

GRANT: We’ve had stories back to re-write before, but we’ve never actually had a Judge Dredd story rejected.

Why was that? Because there wasn’t enough Dredd?

WAGNER: Yeah. It was a story about a Cursed Earth taxi driver and how he came to be a Cursed Earth taxi driver. The first sequence was just taken up with him picking up his passenger. We started that story thinking about a guy crawling through a desert and a taxi coming along. You know the usual image of the man dying of thirst. The taxi pulls up and the driver says “Is your name Jenkins? Did you call a cab?” Without thinking the guy says no, so the taxi drives off. “Wait a minute, wait a minute, I’m Jenkins!” So the cab stops and the guy crawls in, begging for water. But the driver points to a notice: “Sorry, can’t you read? No eating, no drinking.” He drives off and as he does you see another guy in the desert standing with his radiophone and shouting “Hey, that’s my cab!” and he’s also dying. So the cabbie is driving along with this dying passenger in the back rabbiting on, telling him how he came to be a Cursed Earth taxi driver.

That sounds wonderful.

GRANT: You will see it in 2000 AD. They rejected it as a Dredd story, but bought it as part of a new series.

WAGNER: It really irritated us when they rejected it because we tend to know when we’ve written a good story. It was all the more difficult to understand because 2000 AD have bought stories in the past where Dredd made an even briefer appearance. “Citizen Snork,” for instance, the story about the guy with the big nose. In the first episode Dredd only shows up for the last couple of panels.

GRANT: Below a caption that said “Don’t miss next week when the man with a nose for crime meets the man with a crime for a nose.” That was all that Dredd was featured.

I often read your stories without noticing that Dredd isn’t featured too much, I don’t find it important.

WAGNER: That’s the way we feel. After 500 stories, what more can you say about the character? You can just continue repeating yourself or you can change him, and if you change him he would cease to be the character that appealed to so many people. It’s far better to leave him as a presence behind a story featuring his world or an aspect of it.

This may sound a strange comparison, but the way in which your Dredd stories are constructed is very like an American strip called The Spirit.

GRANT: Will Eisner’s The Spirit? His are the only comics I’ve got apart from the stuff we write. I think he’s probably the most creative guy in comics. I don’t know that I’d call him an influence, but I like The Spirit enough to have half a dozen copies lying around.

You both work with a restricted page length, and there’s a similarity in the way that you construct continued stories in some cases, with episodes within a larger framework.

WAGNER: That’s often necessary.

GRANT: It’s because of the artists’ restrictions. You’ve got to do a two or three-parter for a certain artist.

WAGNER: You design a serial that way because it’s quite difficult for one artist to pick up from another on a continued story if he has to have references for characters and background, so we try to sub-divide them.

You have also done some continuous long-running stories. It’s a personal opinion, but I don’t feel that the likes of “The Apocalypse War” or “City of the Damned” have worked as well as the shorter Dredd stories.

GRANT: I didn’t think at the time that the “Apocalypse War” story worked all that well, but having read it in album form, I think it’s a really good story and that Carlos [Ezquerra]’s art-work suited it down to the ground. We were given him for that story as they wanted to use one artist all the way through it. They’ve got constant art problems on 2000 AD finding people who can keep up the output that they’ve got to have. What was the other story?

“The City of the Damned.”

GRANT: That had several artists on it, but the problem with that was that we don’t like time stories and The Mutant was just too powerful and we didn’t really know what to do with him. There was no real story there. It was to clear up the loose ends of the “Judge Child” story.

WAGNER: We got sick of it, and closed it down. It wasn’t working out for us as a particularly good serial, so we thought we’d cut it. I think you’ll find that the new Chopper serial that’s coming out soon will work better as a continuing story because it’s got a better plot. I’d agree with what Alan was saying about “Apocalypse War”. It did seem to work better as an album than as material in the comic.

It just seemed a little repetitious to me.

GRANT: That’s war for you. You do have to read it as an album. I didn’t appreciate Carlos’s art at the time and thought it would be off-putting to the reader. It was quite a grim story really and wasn’t leavened with too much humor, but when you read it in the album there’s enough humorous threads running through it. Dredd has some of his best lines, stuff like “Next time we’ll get our retaliation in first.” Then there was the Russian saying “Should we inform the people?” and his leader saying “The people? What do they matter?” And the next moment Dredd was saying the same thing.

You’ve upgraded the strip over the years. It started as very simple cops and beat ‘em up stuff and it’s now far more sophisticated, even though as far as the editors are concerned you’re aiming at the same sort of audience as you were then.

WAGNER: I think they’ve now come to realize that their audience is mainly fifteen years and up.

GRANT: They’ve only started to admit it recently though.

WAGNER: There’s a lot of adults and college students. I suppose they count as adults as well.

So does that give you more freedom?

GRANT: To a certain point. We still suffer from quite a lot of censorship. Well, I don’t know whether suffering is the right word. Sometimes we write things knowing perfectly well that they’re going to be censored. Sometimes we phone up the editor to check and even though we get an O.K. we still know full well that they’ll be censored.

WAGNER: We do tend to get censored on the strangest things while things that we don’t expect to get by breeze through.

GRANT: We used a city block called “The Petula Clark Slum Block” and IPC’s legal department took exception to this saying that Petula Clark could sue. It became the Mark Clark Block. The story in last week’s 2000 AD, “The Comeback” featuring Michael Jackson’s reappearance in Mega-City One as Jaxon Prince ...

WAGNER: Originally we phoned 2000 AD up and said that we wanted to do this story about Michael Jackson coming back from suspended animation with brain damage and Steve said it was O.K. We said, “No, it’s not going to be O.K.,” and Steve said “Yes, it will, go ahead, write it,” so we wrote it...

GRANT: …and gave it to the artist, and Garry [Leach] drew it and it came in and it was taken straight up to the legal department. They said that Michael Jackson would be suing us and we needed a new name.

That’s when it was changed to Jaxon Prince.

GRANT: Yes, but it was Michael Jackson from the start. It was our tribute to Mike. We put that at the end of the story “Michael Jackson, we salute you.” As “Jaxon Prince, we salute you;” who cares? It had to be Michael Jackson. In the script we have “What’s he saying? Godzilla? Gorilla? I know - it’s Thriller!” – the name of his big hit. They left that in and he looks like Michael Jackson. Everybody knows it’s Michael Jackson and they change the name to Jaxon Prince.

WAGNER: Anyway, it’s not Michael Jackson now, Mike.

You can’t imagine Michael Jackson nipping down to the news agent and picking up his 2000 AD to see it anyway, can you?

GRANT: I can imagine him drinking fruit juices and dancing.

What other things have IPC come down heavily on? Another story drawn by Garry was “Attack of the 50-Foot Woman,” in which you have a nude 50-foot woman for six pages.

GRANT: I was told that it was O.K. to have her nude to start with, but then Steve phoned up saying it would be a good idea if she could have some sort of covering. Another recent one that was censored was “The Beating Heart,” which Steve Dillon drew. I don’t know whether anyone noticed the jump in the story, but it really disheartens you when you read one of your stories and you know that something’s missing from it. There’s a whole page of artwork missing. In that story, a wimp falls in love with a girl but can only bring himself to admire her from a distance. He sets up a camera and bugs so that he can watch her all the time, but she falls in love with another guy. The wimp goes off his head and attacks the object of the girl’s devotions. Because the new lover promised his heart to her, he attacks him with a chainsaw, cuts out his heart.

Just an everyday love story.

GRANT: Well, an everyday love story where one of the triangle is mad. John had doubts about this from the start, so we checked it with Steve and Steve said it was fine, gave it to Steve Dillon and he drew it. It came to the notice of senior personnel at that stage, who said the whole page had to come out, so they just put in a panel that says “He followed him home and killed him, and cut out his heart,” so you actually missed the graphic detail of the heart being cut out. When we discovered that it had been done, John was glad as he didn’t think it was the sort of thing we should be serving up to kids. I think it added to the story.

How depressed do you get about censorship? It seems a common pastime in British comics to see what you can get through.

GRANT: We don’t deliberately try to sneak anything through unless it’s on a very minor scale. We don’t try to get violence into any story just for the sake of it.

So a lot of it is in the artist’s interpretation?

GRANT: No, we quite often tell the artists what we want, it’s just that we don’t throw it in for nothing. We throw it in because we like it.

WAGNER: I knew “The Beating Heart” would be cut. I’m surprised that as much of it got through as it did, but when you’ve got a good idea you want to play it out for what it’s worth and let the editorial team trim it back. I think it would be a different matter if we were selling first British serial rights because then you’d have to censor yourself more.

I’d have thought it would give you greater freedom.

WAGNER: In certain respects, yes. But as far as, for instance, libel is concerned, you’d have to be much more careful. At present, IPC buys all the rights, so if anyone sues, they’ve got to carry the can.

I think almost every other country in the world produces comics that are as violent or more so than the British. It’s more a sanitized violence in the USA…

GRANT: That’s not real violence. The Japanese comics I’ve seen are particularly violent.

I was amazed by their tolerance of sex in comics aimed at children. I’ve got one booklet where a girl is having her breast groped by a cherub. Would you get away with that at IPC?

GRANT: You can get President Reagan in a shower with a male and female bounty hunter.

WAGNER: That’s going to be an interesting sequence.

Have they got their clothes on then?

WAGNER: No, they’re buck-naked.

GRANT: Strontium Dog and Durham Red have to hide out in a shit truck to get away from somewhere, and when they get to a shower Red goes in and Johnny gets impatient and takes his clothes off to join her. The two of them are just starting to get amorous when this head sticks through the curtains: [In a Reagan voice]: “Hi there, guys. Don’t mind if I join you?”

Why don’t they kick up about that at IPC? Is it because Ronnie isn’t likely to walk into his news agent and pick up 2000 AD?

GRANT: We were told that it was O.K. to use him, but some of the things we’ve had him saying have been censored. All references to South Africa are removed, and to the IRA—but we can say as many bad things as we want about Iran or Syria, Nicaragua or anything like that because presumably IPC doesn’t sell copies there.

You do portray Reagan as a bumbling idiot.

GRANT: That’s the impression we get from the TV and the newspapers...

WAGNER: He’s even worse than we portray, if you believe some of the revelations that have been coming out about him.

GRANT: He was referred to in one of the Sunday papers last week as “The Zombie President,” and that fits him quite well.

WAGNER: You couldn’t do that with British figures, it’s too contentious.

At what point do you feel you have to have any sort of moral to the story?

WAGNER: We don’t think about that at all. We go out to entertain and if it’s interesting we’ll write it.

GRANT: Sometimes we’ll write a story like the one with the taxidermist where we could end it with Dredd killing the taxidermist. In a normal Dredd story the old guy would have been caught, but it was just a touch of soft-heartedness that he should get away.

WAGNER: I guess we’re also getting a bit soft in our old age.

Why do you now collaborate on the stories? You were writing Dredd on your own for a long time, John.

WAGNER: I ran out of ideas. While these days I can do four or five, maybe ten of them on my own, by the time that I’ve done that I’m heartily sick of it, so I wouldn’t ever like to take on the task alone again.

So how do you collaborate?

WAGNER: Imagine it like a comedy duo like Galton and Simpson. They sit down, one of them at the typewriter and the other in the chair and they talk, and as they talk they type, and by the end of it the story should have come out.

It’s that instant?

WAGNER: No, you have to get the right basic idea first and talk over certain scenes. Once you’ve talked it out and got the points of most interest to you, you sit down and write it. A long time ago we used to do a construction and try to put each sequence into pictures before writing it, but these days it’s enough to have a rough idea how long a scene will last and where everything will happen.

GRANT: When you know you’ve got a certain number of pages to fill and you know you’ve got an end point for it, you can gauge how long you can let each scene go.

WAGNER: Sometimes an idea can take over a story and it will be totally different from what you set out to write. You often find that the incidental ideas are the most interesting. A lot of the better ideas we’ve used in stories are incidental, they just crop up.

A particular favorite of mine was the idea where the woman bills people for sending them an invoice. It was a wonderfully stupid idea.

WAGNER: It’s not so stupid. There’s money to be made on it.

GRANT: That’s how it ended up as a story, we couldn’t figure out how we could get away with it. We’ve often thought about putting at the bottom of our invoices to IPC “Strontium Dog Invoicing Fee” or “Extra Judge Dredd Invoicing.”

WAGNER: I bet if you sat down and sent invoices to maybe a thousand middle order companies about ten to twenty would pay you just for your invoicing fee. We’ve not totally abandoned the idea.

No one’s pointed out that it can’t be done yet?

GRANT: We haven’t talked to many people.

WAGNER: There’s probably a law against it.

GRANT: You used to read about people advertising in the small ads in publications like Titbits and Weekend saying “Beautiful Miniature Portrait of the Queen. Send £2.50 plus postage,” and they got a normal 14 pence stamp in return. I’ve always admired people that could get away with that. All you’ve got to do is put it in half a dozen publications the same week with a rented address, and then do a hop pretty quickly afterwards.

WAGNER: Not that we would ever seriously consider doing it.

I read somewhere that you’d incorporated fictitious adverts into one of the Otto Sump stories and people actually wrote in for that stuff.

GRANT: That’s what Steve told us. He had letters from kids wanting to buy Blackhead Inducer and Ugly Soap.

The Ugly and the Fatties stories have the potential to offend quite a few people. Has that ever happened?

WAGNER: In one of IPC’s younger comics they had a competition for a funny face, or something like that, and a mother sent in a picture of her Down's Syndrome child and said “This is my child. He’s got a very funny face. Please send my five pounds to...” It’s terrible. And someone did actually write in complaining about the ugly stories saying “I am very ugly...”

GRANT: It was probably me. I think it’s totally reprehensible the way we encourage children to go out and become fatties and uglies. I feel really guilty about it. Although I’m sure life would be more interesting if fatties today took the same sort of attitude as the fatties in Mega-City One. I’d love to see a hundred or so fatties charging up Colchester High Street. As far as the ugly thing is concerned, that’s already been assimilated into today. If you go into Colchester on a Saturday afternoon there are dozens of them lurching around. We were reading in the paper today that people had started dyeing their pets purple, giving them spikey hair and bald patches, so the uglies are here.

Obviously unrepentant about that. How do you account for Dredd being able to adapt to so many different styles of art? That’s very rare indeed.

WAGNER: I think that’s because the character is so strong.

GRANT: He’s got a really good image. Any artist can come along and draw Judge Dredd, and whether or not he draws a good Judge Dredd is the fault of his own artwork.

WAGNER: He’s not really been treated very well. The lead character should be assured a certain standard and continuity of art.

GRANT: With Dredd it often comes down to who’s available.

I would have thought that out of that sort of system you’d often be surprised. If you just went for the established best artist you wouldn’t be seeing John Higgins, who’s currently my favorite Dredd artist.

WAGNER: We did ask for John, so that would have happened in any case.

So there goes my theory that you wouldn’t be seeing him because he only does the occasional story.

GRANT: No, we asked for him and we asked for Cam Kennedy and several other artists.

I think there’s only a couple over the years that haven’t worked. Kim Raymond’s stuff…

GRANT: Abysmal. We requested that after that first story he did he should never be used again, but when Steve got stuck for an artist he gave the scripts to him.

WAGNER: The guy’s a competent-enough artist, but his style just doesn’t suit Judge Dredd.

GRANT: I’ve never met him, and having nothing personal against him, but that’s the worst Dredd artwork I’ve ever seen.

You’re quite vociferous about the manner in which the characters you created have been licensed all over the world making money hand over fist for everyone but yourselves. A lot of people seem to accept it as the way the British comic system has always worked.

WAGNER: I’ve always thought I’ve been very restrained.

GRANT: I’ve been unrestrained about it in the past. I’m a touch more careful now.

WAGNER: I think it’s iniquitous.

GRANT: If we were violent people...

Are IPC actually paying royalties now?

GRANT: They don’t pay us anything. We get one per-cent from the Titan Dredd albums, and that’s all the money we’ve had. I think the most annoying thing about the whole marketing business is that on several occasions we have asked if we could license the rights to merchandise certain aspects of Dredd from IPC. For instance, we asked if we could license the rights to put out a Dredd paperback and it was turned down on a couple of occasions, and we’ve done it for other things as well. Not recently, though, since we got knocked back so often in the early days.

What about selling first serial rights? John mentioned them earlier, so you’ve thought about the production of stories for which you sell first serial rights only.

WAGNER: IPC won’t buy them.

GRANT: And if they do they pay something like 15 or 20 percent of the value. The only person I know who’s ever done it is Kevin [O’Neill] who sold them a series of seven drawings.

WAGNER: And Pat [Mills] sold them a Ro-Busters story.

You have been working for companies in the USA where there are more concessions in the way of licensing rights.

GRANT: We like that.

WAGNER: But communication was initially very bad. It’s not a perfect set-up, but it’s a lot better than what we’re working for.

It seems to me that you’ve been working for so long under the IPC system when there have been other avenues open if you wanted to take them.

WAGNER: I know. We should have thought about it many years ago. Outcasts is a start and we’re pretty pleased with the way that’s going, but we want to do a lot more.

Something that has been announced in the USA is The Last American for Epic.

GRANT: They have the first part of it, but the whole project came to a halt with Mike McMahon’s illness. Mike’s back at work now, but he’s going to have to build up gradually before doing it because it’s a major work, but it should still be go.

WAGNER: If it does go we’ll have to change the story completely. A story that’s been lying about that long loses all attraction so we have to put something new into it to bring it to life for us again.

GRANT: We thought the “Last” angle was a really nice concept. We could do a French one, “The Last Frenchman” or “The Last Swede”—we could have exactly the same comic with a different flag for every country in the world.

What difference do you come across in adjusting to American comics?

WAGNER: We put a lot more work into them for a start, as it’s a longer format. It’s far more interesting to work with. For 2000 AD you write at a much tighter pace because you’ve got to get much more into fewer pages, and it was a difficulty at first to learn to adjust to having more breathing space. There’s more freedom in every way.

You both came out of DC Thomson where they have probably the only proper training system for comics that I know of.

GRANT: It wasn’t really a proper training system. Everyone who joined started off working in the Fiction Department where all the odd jobs were done, like sub-editing the story for the evening newspaper, or the detective story in the Saturday sporting paper, or in my case making up the daily horoscope column.

Making up?

GRANT: I started off sincerely as it was my first rung on the ladder of journalism. I used to try to feel what people would like me to say, but by the time I’d been at DC Thomson for six months I was writing stuff calculated to keep people in their homes—like “Do not go outside today, this is an exceptionally unlucky day for you. A relative has probably died, and if not will die soon.”

WAGNER: I was always wanting to say just a simple “You are going to die today.” It’s a really good introduction to the dishonesty of journalism.

GRANT: Every now and again they shifted your position around within the Fiction Department, so I suppose in that sense it was quite a good training scheme, although I really don’t know how much of it was deliberate. The managing editor would come out in the morning and throw a photograph or an illustration from an American magazine in front of you and say “Right, I want you to write a story about that, and I want it on my desk by such and such a time,” not that they were ever going to be published anywhere. He was quite an idiosyncratic guy and nobody liked him. When he had a heart attack nobody grieved, but I found his methods quite effective.

WAGNER: I came through the fiction department to Romeo [a girls’ romantic magazine].

GRANT: You see, they didn’t know John could be writing boys’ comics.

WAGNER: I think that they took a lot of people on, so some of them are bound to be good. They do tend to throw you in at the deep end as well. You know when you go in there you’ve got a six-month trial period and if you don’t make it, you’re out.

GRANT: Or if they find out that you’re Catholic or Black you’re also out.

WAGNER: Unless their token Catholic has died. Then you might get to stay. What they’d really like to get is a Black Catholic. They do keep a lot of dead wood though. I think the dead wood stays...

GRANT: ...forever. When I worked there anybody with any talent learned what they could from Thomson's and then got out of there fairly quickly, and the people who didn’t have talent tended to stay.

WAGNER: Or people who once had talent and became Thomsonized and stayed and probably lost what talent they had. Well, maybe that’s a bit sweeping.

There was no room for anything but the Thomson view.

GRANT: Certainly not. I had a part-time job as a wine waiter in a local hotel and one night the businessmen’s club held a dinner there and one of the Thomson brothers was the guest of honor. Of course, I was serving him with his wine and he refused to meet my eyes all evening. The next morning I was called in, not by him but by somebody else, and told that I had to give up my part-time job immediately, or I would have to leave DC Thomson. When I asked them why they said that they didn’t want anyone to think that they didn’t pay their employees a good enough wage. I said, “You don’t, that’s why I’ve got a part-time job,” and they said, “But we don’t want anybody to think that.”

WAGNER: You were told to stop wearing your coat, weren’t you?

GRANT: I was going through a secondary hippie phase when I was working for them and I acquired an ankle-length fur coat which I wore into work one morning. I was called into the Managing Editor’s office and told that it would seriously impede my career with the company if I didn’t stop wearing this coat immediately. I didn’t say it, but the guy who had reported me for wearing it was a lunatic. I was standing in the same lift with him and I was wearing my ankle-length fur coat and he was wearing a fishing bag over his shoulder, a hat with flies sticking in it, galoshes and carrying an umbrella—and it was a perfectly sunny day outside.

WAGNER: I don’t think he fished either.

It could be that the reasoning was that if you could afford an ankle-length fur coat people might think you had another job.

GRANT: It was a pretty tacky fur coat.

It sounds like being back at school again.

GRANT: Very like that.

WAGNER: Call it a kind of malign paternalism.

I know John went straight to freelancing for IPC, did you go as well?

GRANT: Yes, but in a roundabout way. I went to IPC, but they were on strike at the time and weren’t taking on any employees, so I ended up doing various other things until such time as they were.

WAGNER: Until such time as you got discovered. He was an accountant for a while. He doesn’t know the first thing about accountancy.

GRANT: I don’t know if it’s a good idea to go into that. They can still take me to court.

It’s that bad?

GRANT: A freight company hired me to find out where a million and a quarter pounds missing from the books had gone, and I’d not got the slightest idea where it had gone and didn’t even know where to start looking. So I compromised by burning the books. By the time I’d finished they’d no idea what they had or what they didn’t have. The funniest thing about it was that when I eventually told them I couldn’t take it any more and I was leaving to go back to Scotland immediately because my granny had died or something, they said “That’s a great shame. You were doing so well we were going to give you our Heathrow account. There’s 5,000,000 pounds missing there.” And I was travelling home from Tilbury at night ripping up the books and throwing them out of the train window. IPC did eventually take me on for a partwork called “Birds of the World,” and I was there until it closed down after six months.

Those partworks always seem to close down after six months. What’s even stranger is that they’re re-launched a year later.

[interruption]

Why do you use so many pseudonyms in your work?

GRANT: It was IPC’s insistence. I think there were several times when we ended up writing all the stories in 2000 AD between us, and the Managing Director reckoned that our names were appearing too often. He didn’t mind us writing the stories, but he didn’t want the readers to know that it was the same two guys doing all the stories, so we started the nom de plumes. At the last count we had about 14. Wes Steele is our latest one. Wes is a hard-bitten writer something in the Marvel manner.

WAGNER: They only credit “W. Steele,” which takes all the fun out.

GRANT: We come up with characters for them.

You personalize your aliases?

GRANT: Oh yes.

What was Craig Lipp?

GRANT: He’s a bit of a mystery man.

WAGNER: What did he write?

GRANT: He wrote “Bad City Blue.” He just burst on the scene like a shooting star and then burst off.

WAGNER: He went supernova.

GRANT: He had his fifteen minutes of fame and went the Andy Warhol way.

What was the one you used for Helltrekkers?

WAGNER: F. Martin Candor. Martins is the newsagent down the road and Candor is the garage where I get my car serviced.

GRANT: And the “F” is short for “fuck.” As you can tell from that, F. Martin Candor is the intellectual in our stable of writers.

What about T.B. Grover then?

WAGNER: That was a name I heard on a radio play. The name was Tubby Grover. He was a school bully.

You’ve recently dropped most of the aliases on 2000 AD Are you now allowed to be credited?

WAGNER: We’re not writing so many stories for them.

GRANT: They’re getting other writers for things like Mean Team, and they’ll probably do a better job on it. Alan Hebden has done a critique and a list of possibilities for the strip, avenues for the story to go down. Most of them lead to the toilet, I would think. That’s not a comment on Alan’s writing, that’s a comment on the Mean Team. I can’t think of any writers I do like.

You’d better explain the Mean Team so that this makes some sense in print.

GRANT: I can’t even remember why we did... Oh, yes. We did Mean Team because Ace Trucking had finished and Massimo Belardinelli needed another story to draw, we needed money and Steve needed somebody to write a story. He said “All the humor in Ace didn’t work, so why not do a story without any humor in it?” Well, we succeeded quite admirably in producing a story without any humor, unfortunately it also had no saving graces.

WAGNER: It did have one good thing, the sportscaster with his dummy. He was in for two frames.

Sportscasters and game show hosts recur frequently in your strips?

WAGNER: I used to watch a lot of game shows, but I don’t any more.

GRANT: I watch the Newlyweds.

Ah, you might be able to confirm this story I heard. One contestant was apparently asked what his wife would say if she were asked “Where’s the most interesting place you’ve had sex?” And he apparently said ‘I reckon she’d say ‘Up the butt.’”

GRANT: I didn’t see that.

You could name a city block after him. How do you name the city blocks in Judge Dredd?

WAGNER: When we have a block we just try to come up with a name that sounds right and is acceptable.

GRANT: We sometimes tailor them to fit in with the theme of the story.

WAGNER: Some people have earned themselves blocks, of course.

You should get people to pay you to have their name on a block.

WAGNER: We did ask for it, but nobody applied.

GRANT: We are open to such offers.

WAGNER: In the introduction to “Block Mania” we said that for 25 pounds you can have a block, for 50 pounds a judge and for 5,000 pounds you can come and write the story yourself while we’re off in Hawaii. We do sometimes do it as a kindness to people. At the last convention a fellow came up to me and said that Hank Wangford was a relative and was really chuffed at having a block named for him. “Billy Bragg keeps going on about how come Hank got a block and he didn’t.” Hank qualified because he’s got a great name. I don’t see Billy ever making it onto a block.

But Billy’s a big 2000 AD fan.

WAGNER: I know, that’s probably one of the main reasons why he’ll never get a block. If Billy does something sensational like getting caught in an Elton John sex scandal he’ll be in there.

GRANT: He’ll have a block the next week.

WAGNER: We’ll give him a condom. Maybe we should do the Elton John Condom. That’s how blocks come about.

Why do you think Robo-Hunter has never taken off in the same way as Dredd? It’s got the same mix of action and humor.

WAGNER: I don’t think Sam Slade [lead character of Robo-Hunter] is as strong as Dredd. He didn’t control the situation. Things went haywire for him because of these two loony assistants, so he failed as a strong lead. We found that we’d rather write about the robot assistants than about Sam. They were good characters but they tended to push Sam into the background.

Strontium Dog carries on and on, but then he’s very similar to Dredd.

GRANT: It’s a lot harder to write Strontium Dog. Stories happen round about him rather than Johnny interacting. He’s always cold and aloof from a situation whereas Dredd just gets stuck in. He doesn’t have the attitude problem. We were getting fed up with Strontium Dog, losing interest, but then something like the current Durham Red serial with President Reagan perks you up a bit.

If you have a good idea for a story do you save it for Dredd or use it as it comes?

WAGNER: If we get a really good idea and it fits royalties work, that’s where it goes unless we desperately need an idea for something else—which is most of the time.

GRANT: So generally we just use ideas as they come.

I presume writing the Dredd newspaper strip uses up a lot of ideas as well.

WAGNER: Are we running through your questions here?

Well, these one-sentence answers do nothing for the word rate. Tell me about the newspaper strip, preferably at length. How did it start?

GRANT: I don’t know.

WAGNER: I don’t know either. The arrangement was made between IPC and Express Newspapers. First we heard was when they asked if we wanted to write it.

GRANT: It’s not a very interesting story, is it?

What about writing the strip itself?

GRANT: At first we thought it was going to be great because as well as the flat rate they were going to give us a percentage of syndication.

WAGNER: No, they never promised anything.

GRANT: Anyway, we’ve now got a half-decent syndication deal on the strip, though. Financially so far it’s not really paid.

WAGNER: It’s syndicated to the South China [Morning] Post and the "Delhi Daily" or something, but we’ve not seen a rupee from it.

GRANT: We couldn’t understand it. We rang up the Daily Star cartoon editor and he read us a list of countries that they’d tried to sell it to. Australia wasn’t interested—and I would have thought that any country would have been interested to have a halfway decent newspaper strip. A lot of newspaper strips aren’t very good. Maybe they should have sold it to South Africa.

WAGNER: Dredd would go down well there. Pik Dredd.

What are the problems of writing a daily strip? You were talking about this when the tape was off.

WAGNER: What was I saying?

I was asking about the difficulties of a three panel strip that has to re-cap each day and then move the plot forward.

WAGNER: What about the difficulties of doing an interview where you have to supply the answers as well as the questions?

GRANT: I didn’t realize that we did re-cap in one picture.

You don’t. John told me that earlier, but that’s the way adventure strips are traditionally handled.

WAGNER: The difficulty is to leave each day on a note of intrigue. Too often a strip will end with a dead end like a guy getting shot, which doesn’t make you want to read the next one.

Do you think many people actually read the strip? The days when people bought papers for a strip have long since gone.

GRANT: My brother reads it and Mike McMahon reads it and Mike Lake [owner of Titan Distribution] reads it. They all buy the Daily Star just for Dredd.

WAGNER: Alan Campbell in Glasgow reads it.

That’s four.

WAGNER: We don’t actually get much feedback on the strip, so we don’t know if anyone reads it. We know that four people read it. The only story I’ve been satisfied with so far was the Weirdies story.

GRANT: It was the first Ian Gibson strip about the annual Mega-City Weirdy Show featuring two-headed people and Citizen Snork with the giant nose. There was the dog-headed man.

WAGNER: Rin Tin Tinsley. It was the man-headed dog, not the dog-headed man.

GRANT: There was the woman who’d had her face surgically removed. She was really great. She kept bumping into things because she couldn’t see where she was going. She had no ears, so if they wanted to talk to her they had to rap it out in Morse code on her skull.

Why did the strip change from a Saturday strip in full color to a three panel black and white daily?

WAGNER: The Star wanted to change their format. That suited us as it was a devil of a difficulty to keep coming up with one-offs. Sometimes they fell a bit flat.

GRANT: A lot of them were very empty, just a punchline with some pictures put in to justify it.

WAGNER: Mills says it’s all the woofters.

What do you admire about other comics work?

WAGNER: You’re on barren ground here, Frank. I don’t read many comics so it’s hard to say. [Long pause] I used to like Uncle Scrooge when I was a kid, although where that would rank in the comics hall of fame, I don’t know.

It’s very highly regarded.

GRANT: I was a Marvel fan for a very long time. I can’t remember what I was. A Quite ’Nuff Sayer or a Titanic something or other. I got a letter from Stan Lee.

WAGNER: You must be a 'Nuff Said Sayer, pilgrim.