GROTH: Well, during this time at Pratt were you drawing comics?

CLOWES: Yeah, kind of.

GROTH: What were you doing in terms of art?

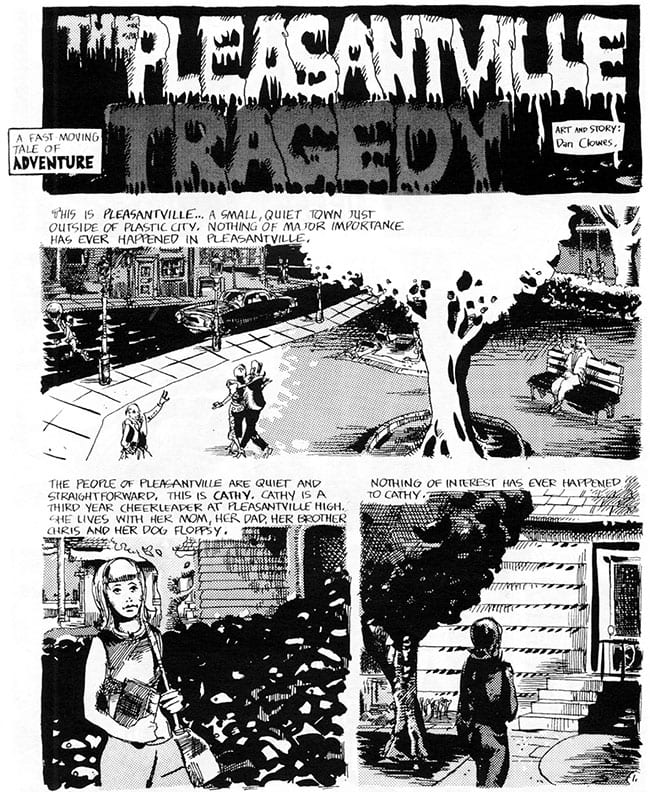

CLOWES: I’d say around the time, from the time I was about 15 until my first years at Pratt I would draw three panels of a comic and I’d get sick of it and I’d throw it away and start a new comic and I’d draw three panels and then I’d get sick of it. I don’t think I ever did an entire page until I met this old friend of mine from high school, Pete Friedrich, who was living in New York and wanted to publish a comic book. We decided at this point we would actually finish comics. Me and my newly-found comic friends. And so I drew, I think, five pages of one comic in one night, you know, at one o’clock in the morning. This was kind of the punk aesthetic, you know — if you can’t do this in one night, it’s not worth doing. I’d just crank it out. And so this stuff was all printed a couple of years later. I was already embarrassed about it by then, but now I am truly embarrassed by it. Although I think it’s pretty funny when I look back at it.

BAGGE: Is that the stuff that appeared in …

CLOWES: Psycho #1

BAGGE: So you drew that stuff sometime in 1980?

CLOWES: No, it would have been ’79.

BAGGE: How’d you hook up with Mort Todd?

CLOWES: Mort Todd was friends with Friedrich. Mort Todd is my friend Mike Delle-Femine, who’s a pretty amazing guy.

GROTH: Why don’t you describe him for us?

CLOWES: He’s just one of these guys who’s got the gift of gab, and he’s always been able to get whatever he wanted. I’ve always envied him. He later became the editor of Cracked magazine. He’s always been able to somehow support himself amazingly well, and then nobody can ever figure out exactly what he’s doing. For this reason, I idolize the guy.

GROTH: How’d you meet comic artists during your Pratt years, if you did?

CLOWES: Well, I would do a lot of solutions to assignments in comic book form, and people would see that and say, “Oh, I like comics, too.” And most of these guys were not the kind of guys I got along with. This was at a time when the big thing in comics was barbarians, or maybe it was kinda after that, but the guys at Pratt were still really into barbarians. In fact, there was a Pratt magazine put out — which I was not in — that was all barbarian stuff. And those guys and I didn’t really get what the other was up to. You know, I didn’t get the whole elf thing. I would talk to these guys and we would be cordial, but we would really have nothing to say to each other, because I had — and still have — no fucking idea what they’re thinking. [laughter] I really don’t understand all that stuff.

GROTH: So who were some of the cartoonists you hung out with in New York?

CLOWES: Nobody famous. Well, Pete Friedrich, who did a comic for Last Gasp last year — he was my only good friend in high school, really. And Mort Todd, who at that time was a cartoonist, though he hasn’t done that stuff in years. And I had a lot of friends like Rick Altergott who had never really done much with the intent of having it published. They just did it for fun. And at that time they were my favorite cartoonists. We did cartoons basically to amuse each other. I went on to actually have stuff published, and they had other jobs and did other things. It takes a certain kind of personality to sit down and do issue after issue of a comic book. These guys had fun doing that one five-page story or something, and then they’d think, “I want to do something else.”

GROTH: So what stuff were you looking at between ’78 and ’82?

CLOWES: Well, I guess Raw came out during that time …

GROTH: So was Raw the first really momentous …

CLOWES: Well, did Raw come out before Weirdo? I can’t remember.

GROTH: They were real close.

CLOWES: Yeah. I remember when Raw came out, I bought three of them, ’cause I knew it was going to be a big deal. I really thought it was going to catch on even bigger than it did, because to me, this was what the world was waiting for. I mean, here was something that was so obvious; why didn’t anybody think of it before? I thought, you get all these good European artists, alternative, weird American artists, and you put them all together in this thing and you sell it to groovy art types. And, of course, at the time I was only hanging out with avant-garde art people who lived on the Lower East Side of New York, so obviously everybody was into this stuff. It never occurred to me that when you go to Ohio or something, nobody in the world would care. There’d be one guy in Ohio who would care about this stuff. But in my little insulated world, everybody cared about this stuff, and I just thought, “This is going to make a zillion dollars.”

GROTH: Did you find it significant?

CLOWES: Well, yeah, to me this was going to open up this huge market for me to …

GROTH: Boy, were you wrong.

CLOWES: Boy, was I wrong. I didn’t only think it would be Raw. I thought that after Raw there would be eight Raw imitators and there would be this huge thing and I would be able to draw enigmatic comics that didn’t make any sense for the rest of my life and get paid for it. It didn’t happen. But I guess Weirdo came out right after that. I was kind of depressed by the first couple of Weirdos, ’cause I wanted it to just be all Crumb, and there were guys like Bruce Duncan in it. I don’t know. It seemed like Crumb had burned out and he had to get these other guys to fill up the pages. It seemed like he was kind of on his last legs and that he would just stop working altogether in a few years. And that really depressed me. I don’t know. I saw it as a sign of hope that there was going to be this kind of publication that I could work on.

GROTH: So, where’d you find these things?

CLOWES: There were these crummy stores in Greenwich Village. I remember that there was one head shop that stayed open for awhile, and they had all their comics hanging from their ceiling with clothespins on ’em. It was right by the Bleecker Street Theater. And all the clothespins had numbers and you had to say, “Number 52.” It was really a lot like you were buying child pornography or something, and you were kind of pointing at them and sweating and the guy would go get it for you and look at you as though you were scum. “Here’s your Young Lust.” So, that’s where I got stuff.

GROTH: Elfquest and Cerebus started publishing in the late ’70s; were you aware of those? And did those mean anything to you in terms of opening your eyes to independent publishing?

CLOWES: Well, Elfquest, if I had seen it, I would have just ignored, ’cause it has the word “elf” in it. Even the word “quest” would have probably turned me off. [laughter] So that was out. I saw Cerebus and it was, like, you know, an anteater with a sword and there was no way I could ever, ever have seen the merit in something like that, whether it had any or not. It was not what I was going to be into. So I never really looked at it, and by the time I was ready to give it a chance, somebody gave me a couple issues and it was so far into the story that I just had no clue as to what was going on. And I’m sure a lot of people could say that about Eightball, so I’m not necessarily saying it’s a bad thing, but I just was never really able to get into it.

GROTH: So after you picked up Weirdo and Raw, how did your interest develop? Did you start reading more comics? Were you more heavily into comics?

CLOWES: Not really. I mean, there weren’t more comics. If there had been more things like that, I would have gotten into it, but …

GROTH: Well, Love & Rockets came out in ’82 …

CLOWES: Yeah. I avoided Love & Rockets for a long time just because I thought it was just, like, a fanzine. I remember when I finally bought it, it was after Forbidden Planet had opened, and I remember that they had a huge stack of them for years, and they were all kind of dusty. I wish I had just bought all of ’em now. Yeah, I finally bought it and I thought, “This is pretty good.” I remember thinking it was kind of a Heavy Metal-type thing when I first saw it. And I really didn’t get what it was. And there was so much stuff like that, the kind of space stuff with girls with big tits, and stuff like that. I wasn’t really reading stuff like The Comics Journal and things like that where I would have read that this was a cut above the rest of the stuff. So I just kind of lumped it together with a lot of stuff. And then when I finally read it, I thought, “Geez, these guys are pretty good.” And somebody told me they were my age, and I got really depressed. I kinda wanted not to like it ’cause they were so good and they were my age, but I couldn’t help but like it. But then it was hard to find after that. The first one seemed to be everywhere and nobody could sell them, and then the next one I saw was, like, number 4 or 5. You know about that better than I do.

GROTH: Unfortunately, yeah.

CLOWES: I guess I didn’t really have an overview of the whole situation to see all these independent comics as being a part of anything. I mean, here’s Raw and there’s this and that. But I wasn’t following the alternative comic scene that much. If I would buy comics, I would look for old, stupid things like old Jimmy Olsen comics and stuff that to me was very surreal. Kind of funny on a different level. And I quickly got, not tired of Raw, but I decided that I didn’t exactly want to be the type of artist that Raw was promoting early on. I felt like it was really too pretentious for me. And I knew that I always wanted to do very traditional, linear narratives, and Raw seemed to be promoting another kind of thing. So I kind of rebelled against that also. I think I’ve always, basically, been an asshole. I mean, I think I’ve always just felt that I should rebel against whatever is around me at the time.

GROTH: You wanted to be contrary.

CLOWES: Right. And here I was, as I say, in this neighborhood where everybody would love something like Raw, so I felt like I should dislike it and do something different, but by doing something different, it didn’t mean I wanted to go and do Spider-Man or something like that. I wanted to do something completely different, and so it was hard to figure out exactly what that thing was.

GROTH: You graduated from Pratt in ’84; what did you do immediately after that? Were you still in New York?

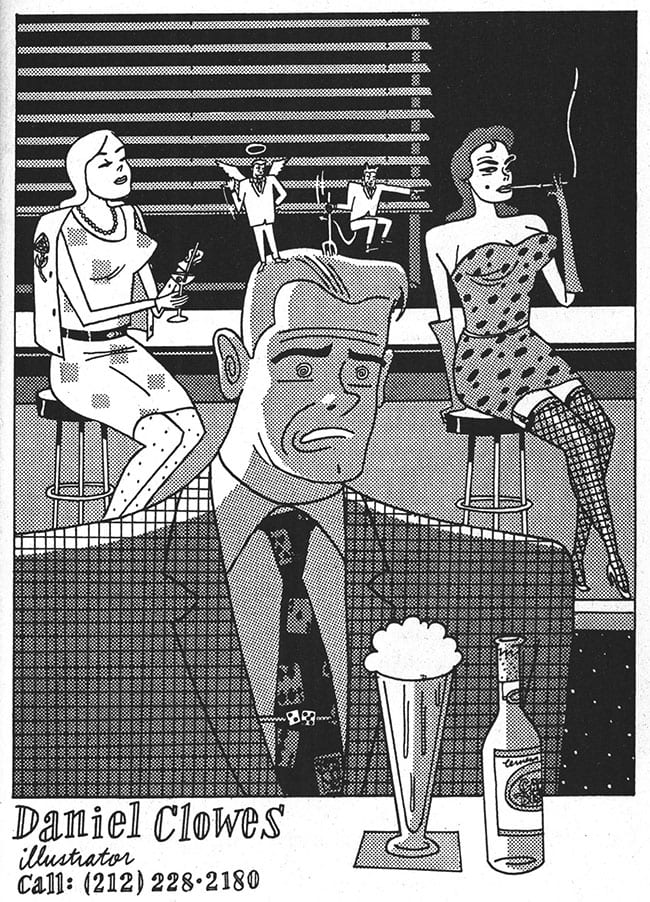

CLOWES: Yeah. I had, by the end of Pratt, put together what I thought was a real top-notch portfolio, with all these really commercial kind of drawings and style illustrations. I thought I was just going to walk out of there and walk into every magazine and they would go, “Where have you been all our life? Do the cover.” That’s basically what my teachers at Pratt had told me. On my final survey, they wrote all these comments like, “Should have been freelancing for years,” and stuff like that. So I thought, “These guys know what they’re talking about,” not realizing that these guys are freelancers themselves, and they hadn’t gotten work, in you know …

GROTH: And they pretend to feel great about themselves, too.

CLOWES: Yeah, exactly. “We should have been freelancing, too,” — but that’s not the case. So, that was the most depressing time in my life. That was even worse than high school, I think, even though I had a girlfriend. I’d call up magazines and say, “What is your policy for looking at portfolios?” And they would say, “Well, you can’t have an appointment with any of our art directors, but you can drop off your portfolio.” So I’d go in and leave it there — anybody could have stolen it. I’d come back at the end of the day; it’s still there, and they’d say they looked at it. I knew they didn’t. They’d say they did. Who’s to know? It’s like, I knew it was happening, and they knew it was happening. I just did it every day, because I couldn’t bear to stay in bed all day, which is what I should have been doing. And so I would go through this charade of leaving my portfolio in different office every day, and that made me feel like I was doing something.

GROTH: What kinds of magazines did you drop your portfolio off at?

CLOWES: Everything. I mean, I went to three a day sometimes. I would go everywhere. I would go to stuff like Seventeen and up to Time and Fortune. And down to the lowest — like doll collector magazines, which I now realize don’t even pay for illustrations. You know, just about anywhere. It was truly depressing.

GROTH: And it was zip?

CLOWES: Nothing. I mean, every once in awhile, I’d get an interview with one of the art directors and they would say, “Yeah, we’ll give you a call,” and I would kinda sit by the phone for a couple weeks, and they never ever would call.

GROTH: Jesus. How long did this go on?

CLOWES: It went on for about four months, I think. And then I was running out of money, and I didn’t know what to do. So that’s when I started drawing the first Lloyd Llewellyn stories, because I had nothing to do, and I thought, “I’d better accomplish something or I’m going to blow my brains out.” I really had no idea what I was going to do with my life at this point. And, right around the same time I was doing that, my friend, the aforementioned Mort Todd, lucked into the job as the editor of Cracked magazine and was able to give me paying work there almost immediately, which was cool. And not long after that, some crazy guy from Thousand Oaks, California gave me my own comic book.

GROTH: Let me skip back a little bit. I’m interested in delving a little deeper into what shaped your point of view, your perception of reality, such as it is.

CLOWES: Are you a psychiatrist?

GROTH: Well, during Pratt and for the next few years, what were you reading, what were you looking at?

CLOWES: Well, umm …

GROTH: What kind of stuff did you gravitate towards? Aside from the Punk scene?

CLOWES: Well, I guess, typical stuff that art students would be into. I mean, that was the first situation I was in where I was able to see the classic art films, and so I went and saw all the Buñuel films and all that stuff. I went to see a lot of underground films. I was really into the underground culture, and the whole idea of it. I still am. So I would see stuff like Stan Brakhage movies, which are really good to see when you’re 19, because they’re really tough to stomach when you’re 30. [laughter] At that age you can say, “Well, I don’t understand this, but I know there’s something deeper to it.”

GROTH: Have you seen tons of Hollywood films?

CLOWES: No more than the average kid. I think I’ve always been really impressionable with films, because actually, I don’t think I saw that many as a kid. I would see them on TV, but my parents weren’t really that big on taking me to the theater. So every time I would actually see a movie in a theater, I would think that it was the greatest movie I’d ever seen.

GROTH: Right.

CLOWES: I would be left with this indelible impression of it in my mind for weeks. I think I’m still like that to some extent. Anyways, I was seeing movies like that, and I was reading Burroughs and Bukowski and all that shit. It’s all so clichéd, it’s hard to talk about.

GROTH: Standard alienated avant-garde.

CLOWES: Exactly, exactly. You know, getting into hard-boiled detective fiction, and stuff like that.

GROTH: Sleazy, hard-boiled detective fiction.

CLOWES: Yeah, yeah. My grandfather was actually an aficionado of that stuff, so he had, like, all the original Jim Thompson paperbacks before he was ever reprinted. I had all that stuff. I mean, I had access to a lot of cool stuff growing up, just ’cause my parents were book collectors and they were obsessive about never throwing anything away — they were real pack rats. So I would read The Evergreen Review and stuff like that. I mean, I was reading a lot of stuff just to have read it, so I would sound cool and I could say, “I’ve read this.”

GROTH: So where did Lloyd Llewellyn come from? He doesn’t sound like he’s in a direct lineage from all of that disenfranchised culture and film.

CLOWES: Well, at the point I did Lloyd Llewellyn I was kind of, again, rebelling against to this stuff. I realized that there were all these other people who were reading the exact same stuff, and I guess it’s always really bothered me to have anything to do with other human beings. [laughter] To have any sameness with the mass of people has always bothered me. I’m trying to work on that now; I’m trying to really make sure I do exactly what I want and not to let the fact that it’s popular influence me. But at that time, finding out that things were popular among a certain crowd of people really appalled me, so, I don’t know, Lloyd Llewellyn was sort of a response to that. It’s kind of hard to say, but after reading all these crime novels, I was really obsessed with all these old men’s magazines and this whole weird vision of the world in the ’50s that never came to fruition. It was sort of building to a certain point, and then the ’60s came down and it never happened — it was this idea of weird space age machismo that was being developed in the early Playboys that really intrigued me. I thought it was basically really sick and really alien to the way I was raised. I just found it very interesting, and Lloyd Llewellyn was playing off that.

GROTH: Well, there was something I thought was in Lloyd Llewellyn that there very well might not have been, since you haven’t mentioned it, but it also seemed that it encapsulated a lot of ’50s TV stuff like Peter Gunn and 77 Sunset Strip. A hip middle-class unreality …

CLOWES: See, I knew that stuff more by Harvey Kurtzman’s parodies of it. I never really saw any of that stuff ’cause I was born in ’61. That stuff was never really rerun. I saw Peter Gunn after I did Lloyd Llewellyn, and I just couldn’t believe that I had copied something that I had never even seen. I guess one of the things about reading stuff like Mad is that these Mad stories were so cool, that you would tend to think that what they were parodying was the actual cool thing and not that Kurtzman was the cool thing. So I thought that the stuff was pretty amazing. But actually at the time they were showing reruns of Dragnet on TV and I was sort of obsessed with those, ’cause that’s the most surreal thing that’s ever been on television. I’m really convinced that Jack Webb is a genius of some kind. He has one of the most recognizable directorial styles of any movie director. Have you ever seen any of his movies?

GROTH: The D.I.

CLOWES: The D.I. is the most crazed movie I have ever seen. A maniac who screams at people and he’s a hero.

GROTH: How about Pete Kelly’s Blues? I don’t know if he directed that.

CLOWES: He did direct it.

GROTH: Did he?

CLOWES: Yeah.

GROTH: Sort of dominated it, didn’t he? [pause]

CLOWES: At the time he was a big influence, ’cause I’d seen a lot of Russ Meyer movies right around this time, and to me there is a real similarity between those two guys. They play everything to such a high degree that it’s got this electricity through it. I mean, a typical Jack Webb shot would be a lawyer in a courtroom and they’re announcing the verdict and the camera zooms in on him and he’s holding a pencil or something, and it would zoom in on the pencil and he would snap it. Something like that really appeals to me. I can watch a movie like that with other people and they would laugh at that, and to me it’s really powerful and electric and I feel a real sense of energy. And that’s what I’m trying to do in my comics — create this kind of energy. It’s something I can’t really put a label on or anything — it’s not something I can figure out a name for, this type of feeling that is created, but I know it when I see it.

GROTH: Like George Bush and the cultural elite? You know it when you see it.

CLOWES: Right. [laughter]

GROTH: This is something that has always intrigued me about you. You seem to have a love for a certain kind of kitsch, like Jack Webb, and on the one hand I can understand your interest in it because it’s so weird, but on the other hand I see it as just another aspect, albeit a particularly weird one, of the great American pile of pop-culture junk. It’s interesting in a very weird, maybe sociological way, but it’s still junk. It’s obviously affected you in a very interesting way …

CLOWES: I always hate to call myself an artist, but when you’re looking at something as an artist, you’re looking at it differently than if you’re looking at it in an academic kind of way. As an artist, if something hits you in a strong way, that’s it, you have no real say over it, that’s just the way it is. And if you resist it, then you’re not really doing your job. If something hits you and you see some kind of power in an image or are feeling some kind of narrative or whatever words give you, you have to either try and react to that, and apply it to your own work, or make some sort of sense out of it, and get something out of it. All of my ideas and all my passion for my work comes from trying to create that in my own work, and trying to create the same feelings that I’m getting from this other stuff. It’s kind of fuel for that. If you get into analyzing it, if you get into saying, “Yeah, Jack Webb was probably a fascist asshole who was probably the biggest scumbag who ever lived,” and you think of stuff like that, it’s just really going to hamper you, ’cause nothing in the world is beyond reproach, and you just end up analyzing yourself to death. So you have to respond to it on a really visceral level, and once you get into sorting out the particulars of it, you really lose something — so I really try not to analyze this stuff. I try to just let it hit me, and do it on my own terms, and then let other people figure it out, or figure it out by myself after I’ve done it.

GROTH: Well, for example, we talked about Sam Fuller …

CLOWES: Right, there’s another example.

GROTH: And I sort of see Sam Fuller as this exquisitely awful director.

CLOWES: Yeah.

GROTH: But of course a lot of people take Sam Fuller very, very seriously, and consider him to be a great director.

CLOWES: The thing about a guy like Sam Fuller or Jack Webb is that they might do something really awful, but they mean it, they’re dead serious, and there is something really powerful about that conviction. To have such a strong conviction, such a strong self-confidence that you would do something so dreadful and not know it, and people around you would be afraid to tell you. There’s a line in The Naked Kiss: he sees a girl and he whistles and says, “I’ll pitch my tent in her bivouac anytime.” [laughter] Nowadays, some script editor would say, “Forget it.” There’d be a red line through it, but somehow Sam Fuller had a certain confidence or power where he got this line into the movie, and there’s a real appeal to that. And if somebody wrote that line in a campy way, I would hate it more than anything in the world. I mean, it would make me cringe and I would want to kill the person who wrote it.

GROTH: No matter how many awful films Fuller’s made, he has these moments in his films that are quite good, and almost poetic in a way.

CLOWES: Well, what I’m looking for in someone like him is not the complete opus, but those few moments of intense personal vision and energy.

GROTH: So as an artist, you pick and choose from all kinds of pop culture. You don’t necessarily say, “This film is so lousy I won’t … ”

CLOWES: I think a lot of it relates to impressions you have as a child. I mean, I can remember watching stuff like Dragnet, and watching old crime movies and stuff as a child, and they had a real strong impression on me. I’ll see kids who are in their 20s now who will respond to something that was going on in my teenage years in the same way, and I can’t really understand that ’cause to me it’s just shit. You know, they’ll like some kind of music in this nostalgic way, like some kind of disco music or something, which to me is just utter schlock — how could anybody like this? But then I have to remember that some of the music I like is probably even worse. And it’s just because whatever it is brings back these feelings of … probably horribleness, because most of that time of my life was really bad. [laughter] But maybe horribleness in its distance is not so bad.

GROTH: So how did you go about creating Lloyd?

CLOWES: I’d had the name Lloyd Llewellyn ever since I was a little kid, because in the old Superman comics, as you’ll recall, they had this weird obsession with the double L’s. They were always making a big issue out of the idea, “Isn’t it strange that Superman’s girlfriend is Lois Lane and his arch enemy is Lex Luthor and then there’s Lucy Lane.” They would get really strange about it. They would say, “Superman went back in time and made friends with Achilles,” and they would underline the two L’s. Things like that. I found that really strange and fetishistic as a kid. I would think, “What’s that about?” And so I remember there was a kid in school named Lloyd and then I heard the name Llewellyn somewhere, and I thought, “What if someone was named Lloyd Llewellyn? He would be the greatest Superman character of all!” I really thought that. Honestly, I thought, “One day I’ll sell this to DC and make a lot of money.” And that was one of these names that kept popping into my head. Once a year I’d think, “Ha ha, Lloyd Llewellyn.” And one day I sat down to draw this comic strip, and I said, “What do I do? How about Lloyd Llewellyn?” And that was it, and that very first panel in that first story was the first drawing I ever did of him. And I was stuck with him after that, and I just said, “OK, he’ll look like this.” There was no thought that went into it at all.

GROTH: No preliminary sketches?

CLOWES: None whatsoever. And I had no real thoughts of him as a character. He was basically a cipher, kind of a straight man to wacky events that would ensue throughout the story. And kind of a stand-in for myself, but not very much so at that point. That didn’t develop until later.

GROTH: He started to look like you, I think.

CLOWES: Yeah. Well, all of my characters eventually start to look like me, ’cause I can’t really draw without looking in the mirror. I have to get the facial expressions perfectly, and when you do that you have no choice but to make them look like yourself after a while.

GROTH: You have a mirror in your studio?

CLOWES: Yeah. It’s an essential thing.

GROTH: So you drew Lloyd out of desperation?

CLOWES: Yeah. Well, it was something to keep me from going nuts, keeping me from becoming a hopeless alcoholic or something. I had to do something with these hours I had on my hands.

GROTH: And you did just one story initially?

CLOWES: Yeah, I’d no intention of anybody ever giving me a whole comic. I intended to do this one story and I thought I would send it around to people and somebody would publish that one story and that’s all I could ever hope for. I thought maybe somebody would say, “This is good; if you work at it maybe you can do a story for us someday.” And I would do something else. I didn’t think you’d be crazy enough to publish it. [laughter]

GROTH: So you submitted it to …

CLOWES: I sent it to a bunch of people. But I guess I sent you guys the deluxe package, because I had seen Love & Rockets and that did seem to be kinda along the same lines. So, as you remember, the first thing I sent you was in color …

GROTH: Yes, it was, right.

CLOWES: And I didn’t know if you guys had ever done anything in color. I didn’t know at the time. And so I thought, “These guys aren’t going to publish this, ’cause it’s in color.” I didn’t really expect to hear from you.

GROTH: Did you get any rejection letters?

CLOWES: I got ignored by most people. Most people just didn’t respond. I remember Eclipse wanted to do something with me, but they wanted me to change the story all around. You guys didn’t want me to change anything, so I thought, “I like these guys better.” [laughter]

GROTH: I read in another interview with you that you hadn’t expected to draw it as a regular comic, so you were surprised that I suggested you make a comic book out of it. But I seem to recall that when I talked to you for the first time and said, “We’d like to publish this as a comic,’’ that your reply indicated that that had been your intent.

CLOWES: Well, I was trying to not sound over-excited. This was kind of what I always wanted to do, you know.

GROTH: You sounded positively blasé.

CLOWES: Well, it was an act. It was just kind of a shock, ’cause I’d been reading The Comics Journal and stuff, and when you called and said you were Gary Groth calling from Fantagraphics, I didn’t really associate you with the mean guy who writes those things in The Comics Journal. It just seemed like it was a joke or something. It didn’t seem real. Of course, at that time I didn’t know the wages I would be earning, as a cartoonist.

GROTH: And what a joke it was.

CLOWES: Yeah, I thought I would be able to move into a nice apartment.

GROTH: So remind me what happened next. You started drawing Lloyd, but obviously you had to be doing something else over the next couple of years while Lloyd was coming out.

CLOWES: Well, actually what I did was I moved back to Chicago and lived in my grandmother’s attic. At the time, I went through this really complicated relationship with this woman and I wound up living in her town and then I moved away, and it’s kind of too hard to go into, but I basically lived with no overhead whatsoever; I had absolutely no bills at all, except for food and stuff like that.

GROTH: That’s how you were able to afford to draw Lloyd.

CLOWES: Yeah. That’s the only way I was able to do it. And I’m so slow that if I had any kind of other job I would never have done it. It just would not have happened. It really takes me a long time to do this stuff.

GROTH: Now, you were living in New York until when?

CLOWES: I had left New York before the first Lloyd was even done. I drew most of it at my girlfriend’s summer house on a little kitchen table.

GROTH: At what time did you move back to Chicago?

CLOWES: This is all real muddled to me, because I moved every month for awhile, and I had all these different ideas of where I should live and what I should do. I just sort of settled in Chicago by around Lloyd Llewellyn #3. I would say I was in Chicago from then on.

GROTH: Well, you did seven Lloyds including the special one-shot, and I think Lloyd ended in ’87. Do you see any evolution over the course of those seven issues?

CLOWES: Yeah. I hope there was a major evolution from issue to issue. To me it was really obvious. To me I was sort of trying something new with each issue. The first one, if I could just fill up the issue I would have been happy. I’d never done a comic longer than four or five pages in my life, I think, and even then it was pure stream of consciousness. I mean, here I was trying to do actual stories with actual plots and subplots that actually worked out. I was just trying to do that in the first issue, and then the second issue I was experimenting. And right around the fourth issue I was getting pretty tired of the character Lloyd Llewellyn, and I felt like I was trapped. Everyone I talked to said, “No, you got to stick with the character — that’s the only way anyone will ever notice you in this comic business.” So I was writing these stories that had nothing to do with Lloyd Llewellyn, and I just figured out how I could plug him into these stories. It was getting kind of uncomfortable, but I felt like I was really learning a lot. I was reading a lot of work by my peers, people like Jaime and Gilbert, and Chester Brown had come along at this time, Peter Bagge and guys like that. And I think I picked up a lot from all those guys, especially the Hernandez brothers, ’cause I think they have this real natural storytelling sense that took me awhile to get. They drew comics when they were kids that were complete narratives. I’m sure that they started out really simply, like just a guy punching another guy and then he flew away and that was the end. But I think that after awhile they developed this intense shorthand of storytelling that was something they just had ingrained — and now they’re able to do it without really thinking about it. And it took me awhile to get that, ’cause that’s not something I really have naturally.

GROTH: How did you teach yourself how to write? This was essentially the first thing you ever wrote. Did you take writing classes at any time?

CLOWES: I was pretty good in high school. I had a teacher who took me under her wing in ninth grade. She was the teacher who assigned The Catcher in the Rye — that’s always an important teacher to somebody like me. Of course, I was the perfect alienated Holden Caufield type, and wrote these really purple-prose angst-ridden essays that she just thought were the cat’s pajamas. And so, at that point I think I learned something about writing. I did a bit of writing. I would write things kind of in script form, more like in play form, when I was in high school. Stuff that, fortunately, I don’t have any more, which at some point I burned. But I think I had a kind of natural sense of writing, ’cause I grew up around people who wrote and read a lot and spoke in kind of an interesting language.

GROTH: So how did you go about doing the first issue? Did you write the entire story first?

CLOWES: Yeah, the first couple of them I wrote, painstakingly, on graph paper, and laid them out several times. I was really nervous. I didn’t know if I could pull this off. At this point, I don’t really even — I just have a story conceptualized completely in my head, and that’s really all I ever do. I’ll write down the dialogue just so I can letter it more easily, but I know everything in my head before I do it. But at that time, I was charting out everything, figuring out where to begin, where the people are in the panels … kind of like what Spiegelman does with Maus. I mean, I’m surprised it didn’t take me a week just to do one panel with all that stuff. I guess I was drawing a lot more simply then.

Eventually, I got a lot more confidence and realized I could eliminate steps that were unnecessary. By the end, I felt like I could pretty much do anything in comics form or do anything I wanted to do. The first couple of issues I was kind of writing around my weaknesses. If I wasn’t sure I could handle a certain kind of sequence, I would just cut it out. But by the end I felt like anything I could think of, I could probably handle. I even remember kind of thinking that as I was working on the last issue of Lloyd, that I had gotten to the point where any idea that I came up with I could probably handle. That’s when I wanted to start something new, because I thought I should be doing something that is not limited in any way. And I always felt that Lloyd was limited just in terms of the fact that it was this character in this world I had created.

GROTH: After you did the Lloyd special, you essentially took a hiatus from drawing comics. I guess in that period you conceptualized Eightball.

CLOWES: Yeah.

GROTH: You were in Chicago at that time. What were your circumstances between the last Lloyd and the first issue of Eightball?

CLOWES: After the Special, I got married and moved to my present apartment. I don’t know if it was a really good idea to get married when I didn’t even have an underground comic book supplying me with income, but I never said I was fiscally responsible. I had some money; I didn’t have very much. And I did freelance stuff. At that time I was starting to get a few jobs. There were a few Lloyd fans out there who liked the look of it, and I got a few album covers and stuff like that. I don’t know what I was thinking. What was I going to do? I can’t imagine what I thought I was going to do for the rest of my life at that point. I guess I really just thought I was going to hit it big with comics someday, and I have no idea why I’d think that. I don’t know; it scares me — I really had no idea what I was thinking. It scares me that I could have deluded myself to that degree, because I really had no future whatsoever. I guess I figured my wife at the time would get through school and support me or something. I don’t know.

GROTH: So how long after the last Lloyd book did you start working on what you considered to be another comic book?

CLOWES: I can remember having a lot of ideas for it, and showing them to you and you just kind of said, “Yeah, OK, whatever.” There’s never really much excitement involved in pitching stuff to Fantagraphics. I think you said, “OK, it’ll never sell.” Lots of encouragement … And so then I hacked it out.

GROTH: What I found particularly interesting was that, it seems to me that Eightball represents a quantum jump from Lloyd in terms of ambition and quality. I’m wondering what happened to you between the two.

CLOWES: Well, as I say, I was kind of busting to do that from about Lloyd #4 on, so all the ideas that were in Eightball were going through my head. At the time I started Lloyd, I would have never thought of doing something like Young Dan Pussey, because I knew I couldn’t really pull it off, and I wouldn’t have had the confidence to do it — or “Velvet Glove” even more so. Around Lloyd four or five, I kind of realized maybe I should do something different. Lloyd had to have a certain kind of linear narrative. I always liked the idea of comics as short stories that can be read quickly and that are just entertainment. But then I wanted to do something more substantial. So when I had the opportunity to do Eightball, this was all the stuff I’d been thinking about for years at this point, and I had all this energy to do it, and I had confidence. Also the fact that it wasn’t going to sell and that nobody was going to look at it really gave me this feeling that I should just do whatever I want. With Lloyd, I was trying to appeal to this imaginary audience that I felt existed that really didn’t — hip, urban types that would dig this stuff, and there is a certain crowd of people like that, but not nearly enough to support something like that. So I thought, “I got nothing to lose, this is just going to be another failure, and I want it to look good.”

GROTH: So my apparent apathy actually encouraged you.

CLOWES: It spurred me on to even greater heights of whateverness.

GROTH: And to support yourself while you were doing it, you just did commissioned jobs occasionally?

CLOWES: Yeah. I mean, I lived pretty cheaply. I’m not extravagant anyway. At that time, I was spending all my time drawing, so I didn’t really have time to waste money on anything.

GROTH: Eightball is so completely different from Lloyd, because first of all you have the “Velvet Glove” serial, then you have these short strips that range all over a number of subjects, but there’s a consistent tone throughout the entire book. Was this a carefully calculated strategy?

CLOWES: [laughs] Yes, it was a carefully calculated strategy to sucker the masses into buying my comics, into swallowing my destructive philosophy … No, not at all. I wanted to basically do a title like Humbug or Help!, or Mad or something, but it would all be done by one person. It was like I wanted to do an anthology — it’d be more like a Weirdo — I wanted to do an anthology comic, but it’s all by me. I’ve always felt that I had all these different, very unrelated parts of my personality, and I wanted to be able to do stories with each of these different parts of my personality in the same book, and then have somebody else look at it and go, “OK, I sort of understand what this guy is all about.” But I was really worried that people would see the first issue and think that there was just no consistency at all and say, “This is just all over the place, and I have no idea what this guy is going for.” So I guess there is more cohesion to my thinking than I realized.

GROTH: The “Velvet Glove Cast In Iron” title, although it’s mentioned in Russ Meyer’s Faster Pussycat, actually appeared earlier as a phrase in a hard-boiled detective novel?

CLOWES: Yeah, I’ve seen it a couple places actually, and it’s in a couple of slang dictionaries. Because when I heard it in the Russ Meyer film, I thought, “What the fuck does that mean?” I still really don’t understand what it means. There’s another phrase, “like an iron fist in a velvet glove,” or something like that. It basically means it’s something that’s couched in femininity, but it’s actually very tough and masculine, that kind of thing. But I just thought it was a very evocative phrase.

GROTH: How did you create the Velvet Glove serial? Did you have the entire story in your head?

CLOWES: No, no, not at all. I was writing it page by page for the first couple of episodes. It was based on two or three dreams I had had at the time and one that my ex-wife had had recurring throughout her life — that whole part of the underground parking garage, that was this dream she’d had several times. I just sat down one night and wrote down the whole thing. It just kind of came out — it was very easy to write. I mean, the whole story has been really easy to write. I never had any blocks of any kind; it just flowed, and everything just matched up perfectly. I’m trying to write in an intuitive way; I’m not trying to overintellectualize the writing process. I’m trying to actually understand the characters, and write them as though I am sort of embodying them, trying to think as they would think, and let them go where they may. It’s kind of a huge experiment, and it’s a lot of fun to do. That’s the main thing: to keep my interest level up.

GROTH: Did you determine at some point where this story was going to go and where it was going to end?

CLOWES: Yeah, at a certain point you just can’t help but go a couple different ways. When I’m writing one episode I start to think of the next episode, and then certain ideas come to the forefront and other ideas seem really stupid after a while. I have certain notes that I read and I can’t believe I was ever even thinking of doing some of these things with my characters that I know now they would never do. Like I had an early notebook with the character Tina, and I was going to have this scene where we just cut to this guy and he’s talking on the phone and he’s masturbating — it’s like a phone sex thing. Then it cuts to his fantasy, and he imagines himself with some blonde with big tits and he goes through the whole fantasy and then he hangs up the phone. And then it cuts to Tina, and she’s the phone sex girl on the other end of the line, and that was the reality of this thing, this horrible, sad dolphin-woman. And after I wrote one of the stories, I realized she would never do that — she’s completely innocent and would never work on a phone sex line; it just would not relate to her character. I had these ideas like that, and I had to edit them out because I realized this was not true to the nature of the story and the nature of the character. After a while it just writes itself; it takes on its own life. You can guide it in different directions, but you have no real control over the whole thing.

GROTH: Now in something like Velvet Glove, which is a really long story, do you make discoveries about yourself as you write it?

CLOWES: Oh yes. One of the things I’ve tried to do is to keep all of the mysteries alive for myself. Because I think once you know the solutions to the mysteries, they’re not interesting at all anymore. I’m trying to write about things that I am deeply afraid of and concerned with. It’s like constantly poking a wound, and keeping myself moving by doing that. Because when I see something like Gilbert Hernandez who can write an entire opus, and I think he really plans it out before, and I think he knows, when he introduces a character in the second chapter, that they’re going to reappear at some point and do this and that …

GROTH: Yeah …

CLOWES: And I’m incredibly impressed by that, but I know I could never do that; I know I would lose interest, or I would change my mind along the way and then I’d be stuck with whatever I’d done. So I knew the only way I could do a long epic story was in this way — where there is so much leeway for a while, and then after a while it would just write itself, and I wouldn’t ever really have to agonize over it, because it’d be just too painful and paralyzing for me.

GROTH: It also seems to me that with Eightball, your drawing style suddenly matured into something that was barely detectable in Lloyd. Did you work on that?

CLOWES: Well, see, that’s another thing. With Lloyd, I had to draw it in the style I started out with. And if you were to look at my sketchbook drawings from that era and other drawings I did, they were really very different. Lloyd was a character almost like Nancy or something, like two dots and a line. And all the drawings in my sketchbook were kind of like, almost like Drew Friedman or something — very, very different. So that was another thing I was itching to do, all different kinds of drawing, and that’s something I’ve always wanted to keep up with in Eightball, to have all these different drawing styles, to really have a lot of variety. That’s another way in which I wanted it to look like an old Mad. I was trying to almost create something for myself that I wish existed, or to create for the world something I wish existed.

GROTH: Do you draw very slowly?

CLOWES: I’d say I’m pretty slow, yeah. It takes me about three days to do one page. I mean, I’m not the slowest guy in the world, but it would be nice if I was a lot faster. I can’t believe these guys who can do a comic in a month or two. But they have letterers and inkers and stuff like that, and I’m kind of fetishistic about doing it by myself.

GROTH: Where or how did you learn to letter?

CLOWES: It’s something, I guess, that just came naturally, because I always lettered my own strips. I guess I copied different letterers, like most people copy the Marvel letterers, and I was always intrigued by the guys who lettered the old Spirit sections, the typewriter serif lettering. The old Dennis the Menace comics had really good lettering. I always wanted the lettering to have a different look. I always thought lettering was really important to a comic. The way you letter something really affects the way it’s read; it affects the intonation that each character puts into what they’re speaking. Walt Kelly is the only guy who’s ever really played with that, that I know of. Kurtzman saw the importance of it and always had the hand-lettering, and that really gave a kind of jaunty look to Mad, as opposed to the real tight-assed Leroy stuff.

GROTH: I have to admit some of the lettering in Lloyd really drove me nuts.

CLOWES: Yeah, Crumb told me, when I first met him, that he was really glad I had stopped lettering like that because he could never read it.

GROTH: One thing about your drawing is that it’s graphically sophisticated …

CLOWES: I’m a sophisticated kind of guy.

GROTH: Did you work toward that end, or was it not even something that you …

CLOWES: No, that comes out of the whole desire to be a big-shot slick magazine illustrator. Because I wasn’t really interested at all in the slick magazine illustrations that were going on in the ’70s or ’80s or any of the years in which I was looking for that work. I was really into the old stuff from the early ’60s and late ’50s, and that’s where a lot of the Lloyd graphics come up. So I was looking at a lot of old art directors’ annuals, and paperback covers, and I always collected records just for the sleeve art and things like that. There is a sense of design that kind of left us in the mid-’60s and never really came back. I’ve always been kind of attracted to that — but now I’m kind of less attracted to that and I’m trying to get this more homegrown look to my art.

GROTH: A little cruder?

CLOWES: Not necessarily cruder, but just something that you know is not done by a computer. Something that really annoys me is when people always ask me if I use computers to do my drawings. That happens a lot.

GROTH: Well, your work reminded me very much of Krigstein’s, with its geometrical compositions and patterns, but I read that you hadn’t even seen Krigstein’s work until after you had drawn Lloyd.

CLOWES: I’d seen “Master Race,” and I’d seen one other story that’s in that big EC reprint book. I thought they were great. But I really hadn’t seen much else by him. I don’t know, I guess you can be influenced by one story. He had this really ’50s ad art look to his stuff that was very designed, kind of geometrical, where all the angles of the lines drawn really make these very distinct patterns; his layouts were all based on lines rather than shapes, and things like that, so that had probably a lot to do with it. When I first started, a couple of people said, “This looks exactly like Krigstein’s art,” and it really upset me because I thought that I wasn’t fit to wash Krigstein’s brushes, and if somebody thought I was already that good, what was my incentive to even try it? If I ever did get as good as him, nobody would notice, so what’s the point? But I don’t think people say that so much any more.

To me, my art looks perfect when I do it. I mean, it’s really what I see in my head. To me it looks almost like a diagram or like a coloring book or something. It really looks very … I don’t want to say bland, but it just looks very perfect. It looks exactly the way the world should look. And I don’t see a style at all. I see it as being each face is the way a face really looks. I mean, when I look at somebody’s art, like Johnny Romita or someone like that, every face is very standardized and perfect. My art, to me, almost looks like that. And then people tell me they can recognize my style, and I don’t understand what they’re talking about. I don’t see my style. I know a lot of artists that feel that way.

GROTH: Yeah, I suppose that’s the way you see the world.

CLOWES: Yeah.

GROTH: I mean, to you that’s objective reality.

CLOWES: I’m trying to get the exact image I have in my head onto the paper. And I think the closer and closer I get to that, the less style I can see. I mean, I don’t want there to be a style.

GROTH: When was the first Eightball published, ’89? Were you paying much attention to what was going on in comics at the time?

CLOWES: Oh yeah, sure. At that time, it was my business. I mean, I was so bitter about all the stuff that was going on that I would sort of pay attention to it even though when I would look at things like the Comics Buyer’s Guide I would tear it up into little pieces and say, “I’m never going to look at that again; that’s too depressing!” But then of course the next time I’d see one I’d read it again.

But what fueled all the Dan Pussey stuff at first was going into comic book stores and seeing people buy hundreds of copies of Green Lantern or whatever, and be not even disinterested in the kind of stuff I was doing, but rather almost actively opposed to it, like they’d really like it to leave their store and stop offending them. You see that a lot at these conventions — people kind of look at your stuff with hopeful interest thinking it’s going to be a drawing of Wolverine or whatever, and when they see what it is, they’re so put off by it, it upsets their comic universe or something.

GROTH: Their perception of the way things ought to be.

CLOWES: Yeah. This weekend, for the first time, I was really trying to imagine myself as a guy who is into superhero comics, what he would think of my kind of comics. And all of a sudden I felt like this complete degenerate, because I can imagine they would just think it was this utter shit, this utter filth, scum, bullshit, pure garbage farted out by degenerates to try and get a rise out of people.

GROTH: Yeah. This is probably completely worthless as far as the interview goes, but there was this hilarious scene at the table: this guy walked up to me and he wanted to know if we used artists. I said, “Yeah.’’ He said, ‘‘Well, I’m an inker, and I’ll ink anything. I just want to ink.” I think I said something like, “Well, do you also draw?” He says, “No, my drawing’s awful. Can’t draw very well at all.” So I said, “Well, that’s too bad, because all of our drawers don’t draw very well, and we need inkers to draw real well to make up for their deficiency.’’ And I sent him on his way. But he accepted this as pretty reasonable.

CLOWES: The amazing thing is that there are a lot of guys like that, who can ink and they can’t draw. That’s pretty remarkable. I mean, it’s really remarkable to have so little ambition that that is your end goal, to be an inker. There’s pleasure to be had in inking, I suppose.

GROTH: Just as there’s pleasure to be had at plumbing.

CLOWES: Yeah. Inking is part of the process where you can listen to the radio and talk to people and talk on the phone and do things like that, because it doesn’t take much thought, and to me that is a natural part of the process, ’cause you put all your effort into writing and penciling, and then inking and lettering is kind of a break from all that, and then you go back into it. It’s a cyclical thing. But to do it all the time is very strange. It’s like sleeping all the time.

GROTH: Well, I would assume, and I don’t even know if you can tell me if this is true or not, since you don’t see it from the perspective of an inker …

CLOWES: Well, I’m an inker, of sorts …

GROTH: Yeah, but inking someone else’s work would seem to me a very mechanical process.

CLOWES: I’ve done it and it’s completely mechanical; it’s tracing, it’s connect the dots, pretty much.

GROTH: Yeah, right. But when you do it on your own work, I would assume it’s not a mechanical process because it’s an organic part of the art.

CLOWES: Yeah. When I’m penciling, that’s when most of the creative process comes in. Inking, all I can do is kinda tweak it either way. There’s no real great things that can be done — I can’t save a bad drawing, I can’t make an undramatic situation dramatic, but I can push it, and that’s what inking is. They used to call it embellishing at Marvel Comics; the embellisher, that’s not a bad word for it. It’s what you do.

GROTH: Of course, a lot of decent penciled art can be ruined by inks. So it’s good that you don’t do that.

CLOWES: Yeah, it’s true. [laughter] Inking is when you’re doing your real comic book stuff. That’s when I feel like I’m a real comic book artist, like some guy working at a sweatshop. I’m inking. Getting that line is real important to me, ’cause that’s what impressed me about comics when I was a little kid. I remember looking at Superman comics and not thinking, “How can Superman fly?” but, “How did that guy draw that line?”

GROTH: Because it was so perfect?

CLOWES: It was a perfect line. It took me until I was 25 years old to draw a line like that. Every once in a while I’ll do a line like that — I’ll draw a face or something, and I’ll look at it and go, “God, if I knew I could do that when I was six years old I’d be so proud of myself.” This is what I’ve always dreamed of doing.

GROTH: And learning to do that is a matter of repetition and practice?

CLOWES: Yeah, sure. There’s no tricks, you’ve got to do it a million times. All my life I thought there was a special pen they used and I tried every kind of pen known to man, and it’s just a brush.

GROTH: Is learning how to use a brush very difficult?

CLOWES: It was for me, yeah. Yeah, it is … For God’s sake, we’re talking about inking! What are we doing?

GROTH: Jesus Christ, that is pathetic. What the fuck is happening to us? Let’s talk about Dan Pussey and the comics milieu you’re satirizing.

Actually, I’m not sure what needs to be said about it, it’s so perfect in and of itself. How much do you truly dislike the environment you’re satirizing in Dan Pussey?

CLOWES: A lot. The thing is, I don’t have anything against superhero comics, per se, or anything like that. That’s the kind of thing that if it was on the level that it should be on I would just think it charming, little, nice American fun, like Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny. But the fact that it dominates my life to this degree is very upsetting to me. The fact that I have to explain myself to anybody who is not completely involved in this business pisses me off. And I really hate to have to tell people that, no, I don’t draw superheroes and I don’t do Garfield. I think what I do is not that strange, and the way people think of it as a crazy, wacky thing that nobody would be interested in really bothers me because I think that a lot of people would be interested in it. And I hate going into a comic shop and it’s 99 percent superhero stuff, and there’s just a little corner with my stuff and my friends’ stuff.

And it bothers me that I can only go out and buy three good comics. I like to read comics. There’s nothing that I like more than to read comics. And it bothers me that I’m denied this because people don’t know to enter the field of comics. People become other things besides cartoonists because they never thought of it, because there aren’t enough good ones to bring them into the field.

GROTH: It’s just as you said — it’s poisonous; it’s not like you’re doing satire after satire of Son of Flubber films.

CLOWES: That’s the point, people just started to take it for granted that comics are about superheroes. And they don’t say, “What if all TV shows were about clowns that were addicted to drugs?” It’s about the same thing.

GROTH: I do run into people who have almost the opposite attitude, which is they take it for granted that superheroes are bad, and they don’t understand why you’re wasting your time satirizing them. In fact I think that, in an otherwise perceptive review of Eightball, Andrew Langridge mentioned that Dan Pussey was one of the weak spots.

CLOWES: Well, I was going to say that that seems to be a European attitude. I heard that from a couple of people overseas who said, “I really liked Eightball, but I found the Dan Pussey stuff way too obvious. Why are you poking fun at the most obvious target in the world?” I think maybe their comic scene is a little different from ours. I don’t know; I’ve never been over there.

GROTH: They have not witnessed the true horror of our comics industry at close hand.

CLOWES: The stuff I see from there is just slicked up superhero stuff for the most part. That story just had a lot of true rage and frustration at its core. On the other hand, I kind of have this empathy for a guy like Dan Pussey, ’cause these guys are kinda sad, but they don’t know it and that’s what makes them so annoying. I mean, if they knew they were sad they would be really sad.

GROTH: There’s not even a tragic dimension to them. There is no self-awareness.

CLOWES: But I mean, a nerdy guy who’s only into superhero comics is probably a lot more interesting than a lawyer or a suburban businessman. I mean, here is some guy who at least has some connection to his imagination. It’s not like he’s the worst person in the world, some guy who reads comics. It’s just that I expect more out of these people; I expect more out of people in general. It really frustrates me that they won’t do things my way.

GROTH: No wonder you’re nihilistic — expecting more out of people.

CLOWES: Yeah, it’s tough.

continued