GRAMMEL: How did you get the name Yummy Fur?

BROWN: I don’t know. I just had to come up with a name for the comic book, so I was going through all kinds of titles, and Yummy Fur was one of them. Also l wanted a title that wasn’t going to tie me down to anything. In the beginning I had all these different short stories, and there was no central theme or character. I didn’t want a title tied to any character or anything like that — just a kind of general name. So Yummy Fur doesn’t mean anything, so I called it that.

GRAMMEL: So you published the minis yourself, then what happened?

BROWN: A lot of people in Toronto were self-publishing at this point, standing out on the street with a sign around their neck, saying, “Buy my book,” or whatever. Chapbooks, poetry, that kind of stuff. The real father in Toronto of this movement is a guy name Crad Kilodney, who puts out his books of fiction — mostly short stories, but also novels. He just stands on the street and sells them that way. And he still does it, actually. You can still go downtown and see him. A lot of other people saw Crad doing this and so they were all doing this. Mark was doing this, too — Mark stood out on the street. Actually, I was looking through stuff the other day. I got this out. [Chester produces the sign which shows a Bob Kane-style Batman and Robin with fangs and a dead rabbit.]

GRAMMEL: [Reading]: “Buy my book.”

BROWN: So I stood out on the street like this. [Stands with sign hanging on his chest from the rope around his neck.] This actually wasn’t a good sign. It’s too complicated. You have lots of little reading that people have to do. You want a simple sign that will grab people as they come by, and this one’s too complicated. But anyway, the first issue was published. It came out July 1983, so this is like mid-summer. So I went out on a Saturday. Kris came with me. We stood out on the street.

It was a boiling hot day. It was so hot, and I had to take off my shirt, and Kris was saying, “Don’t take off your shirt. People won’t buy from you if you’re half-naked.” But no one bought a copy. I thought, you know, “25 cents, sure, someone’ll buy an issue.” But no one bought an issue. Some people would come by and read the sign and walk on. A couple people asked what it was about.

GRAMMEL: So if you were begging you would’ve been making more money, [Laughter.]

BROWN: Probably, yeah. So I just got so discouraged that that was the one and only time I did that. So this sign got one day’s use and that was it. It was hung up after that.

GRAMMEL: Eventually you began doing some mail-order stuff.

BROWN: Yeah. After standing out on the street I figured, “Well, I’ve got to sell these some way,” so I went into a whole bunch of stores around town. A lot of people picked them up that way. Most stores did it on consignment, but a few bought from me straight. And we have a lot of bookstores in Toronto. So I don’t know how many took it, but there were quite a bit. Then this guy in town, Peter Dako, saw that I was doing Yummy Fur, so he said, “Well, I can do the same thing,” so he started putting out his comic book called Casual Casual. And this other guy who’d been self-publishing his comics, Michael Merrill, a Toronto artist, he got in touch with us. And we all got together and Michael had a bunch of these minicomics that he’d got from Am Saba.

GRAMMEL: Is he in Toronto?

BROWN: Am Saba? Yeah. So Peter and I went over to Michael’s one time and there were these minicomics all on this table. He’d brought them all out. And it was amazing. “You mean there’s a whole bunch of people doing this?” And most of them are awful, but it was amazing to me that other people were doing it. So I got in touch with some of the people in some of the minicomics, and started getting into the network this way. And there were these fanzines devoted entirely to minicomics and so I’d advertise in there. It got quite a bit of response, it was actually about 50/50: 50 selling to the stores around Toronto and 50 by mail. Something like that.

GRAMMEL: How many copies of Yummy Fur were selling by the end of its life as a minicomic?

BROWN: I’d print a couple hundred at a time, but I’d reprint as often as necessary. So I guess for some issues it got up over 1,000.

GRAMMEL: Tell me about how you made the jump from your minicomics status to having your own comic book. Was that a big thrill for you?

BROWN: Oh, yeah. It was a big thrill. I was doing Yummy Fur, but it was getting to the point where I was wondering, “Am I going to be doing Yummy Fur as a minicomic for the rest of my life?” I wasn’t sure. At a couple points I’d said, “No, I’m giving up doing minicomics.” Because at this point I was also starting to get people like Fantagraphics and Kitchen Sink asking me for submissions to their anthology magazines like Honk! and Prime Cuts and Snarf, whatever. So I was kind of wondering, you know, “This is great, but I’m not going to make money off of this.”

So one day early in ’86 Bill Marks phoned me up out of the blue. I was out late doing something, and right when I get home the telephone’s ringing. So I answer it, and it’s Bill Marks apologizing for calling so late and hoping he hadn’t woken me up, but would I like to do Yummy Fur as a comic book for Vortex. And so I said, “Well, it sounds good. Let’s get together and talk.”

So we did. He convinced me to go with him. It wasn’t all that hard to convince me, actually. Well, I did have some reservations — hearing about the Hernandez Brothers and other rumors and stuff about Bill that I’d heard. I’d met him a couple of times before, and he always seemed like a nice guy. I always got along fine with him. So I was taking what I was reading in The Comics Journal with a grain of salt, not being sure how much… You know, thinking, there’s always two sides to every story.

GRAMMEL: Did he naturally assume that you’d have ownership of the comic book?

BROWN: Oh, yeah. That was never a question.

GRAMMEL: Let me ask you this. Do you work with a contract?

BROWN: Yes, I do. [Laughter.]

GRAMMEL: I’m guessing that your contract is for a limited time. Have you received any offers to transfer Yummy Fur to another company?

BROWN: Oh, I’ve definitely gotten offers.

GRAMMEL: Do you feel loyalty to Bill Marks because he was the one who made the effort when no one was knocking on your door?

BROWN: Precisely. I do feel some measure of loyalty to Bill, and I’m not going to leave Vortex just for no reason, and I get on with him fine. I have no problems with him. He lets me do whatever I want.

GRAMMEL: You don’t want to be in color, so that’s not a problem.

BROWN: No, I am happy with black and white. So I don’t foresee changing companies in the near future. I don’t foresee changing companies at all unless I have to for some reason. And also it’s just easy working with Bill. I was going to say he’s here in town, actually he’s just about to move out. Vortex is moving to Picton. Picton, Ontario.

GRAMMEL: Probably cheaper rent there in Picton.

BROWN: Yes, that’s the thing. You’ve never heard of it, but neither has anyone. Anyway, he’s still close even in Picton, so there’s not even that border barrier.

GRAMMEL: I’m sure you’d somehow like to see your work branch out of the comics ghetto. I’m sure you’d like to go into a Barnes and Noble or whatever and see a Yummy Fur collection that you’ve done in a book form in there. Do you think that through Vortex, in the foreseeable future, you can reach that market? I know Fantagraphics is being distributed by Berkeley Publishing. And I’m not shilling for Fantagraphics, either.

BROWN: Certainly I’d like a wider audience, but if I can make a living doing what I’m doing, then that’s fine. It doesn’t matter to me if it takes a while to break out of the comic book ghetto. I’m a patient person.

GRAMMEL: You’ve said that the reason you wanted to write was to have something to draw. Have you ever had any training in writing? Have you ever written any fiction?

BROWN: Nothing beyond what you get in high school or college.

GRAMMEL: Which part is harder for you then, writing or drawing?

BROWN: Well, when I do a comic I tend to think of them together. But when I get stalled it’s because I don’t know what’s gonna happen next, which is the writing, the plotting.

GRAMMEL: Do you ever feel like working with other artists or writers?

BROWN: I really like the idea of collaboration. It seems I do my best work by myself, but I really enjoy — actually I probably enjoy more — collaborating with people.

GRAMMEL: So you’re talking just in terms of what’s more fun — sitting alone or sitting with someone else?

BROWN: Yeah, I guess so.

GRAMMEL: Early stories — “Bob Crosby and his Electric TV” and “Catlick Creek” — have clear cut axes to grind, and I don’t see this much in your most recent stories. Were you uncomfortable with that way of working?

BROWN: Um, a bit. I don’t think much of “Catlick Creek” now. Earlier you asked, “Is this a true story?” And a couple of people have asked that afterward, and I don’t think... if that’s the question you ask I don’t think it worked. It shouldn’t have looked like I was just taking a story from real life and redoing it. It should’ve worked on its own merits or something.

GRAMMEL: Well, “Bob Crosby” is a little different because it is more of a story. How do you feel about the story?

BROWN: I think it’s a bit too obvious now. A bit too simple. And I thought that at the time I was doing it, but I did it anyway. I like it... I like the way it’s drawn. At that point I was still doing brush, and I think it’s one of the best things I did with brush. So I like it just from the drawing point of view. Well, as a story it’s not bad. It’s OK I just don’t think it’s one of the better things I’ve done.

GRAMMEL: Do you think that art should teach us something? This is a Journal-type question.

BROWN: There’s nothing wrong with learning from art, but I don’t think it’s the artist’s purpose. I mean, the artist shouldn’t set out to teach. The artist just talks about, I don’t know, whatever he wants to talk about, and people take from it what they will.

GRAMMEL: When you do your own work do feelings that are vague in your own mind become clearer to you?

BROWN: Oh, yeah. Definitely.

GRAMMEL: So is that one of the impulses when you do work, to resolve how you feel about things?

BROWN: Yeah, definitely. I mean. Yummy Fur may not be a learning experience for anyone else, but it is for me.

GRAMMEL: Can you give me one or two examples of this?

BROWN: I’d been seeing these different Japanese comics, and the way they were obsessed with doing jokes about… Doing shit jokes and stuff. Scatological stuff. And I thought it was kind of disgusting, and I couldn’t see why the Japanese would be so obsessed with this stuff. So I decided to put it in my comic and see how it would turn out. And after drawing “The Man Who Couldn’t Stop” I didn’t find it disgusting anymore. Now when I see that kind of stuff in Japanese comics or anywhere else, it doesn’t bother me the way it used to. So by working it out, by doing that kind of story myself...

GRAMMEL: It lost its power to offend you?

BROWN: I guess so. Yeah.

GRAMMEL: Different writers start off differently. Some begin with an image, some start with a character, some with an issue they want to grapple with. I’m just wondering, when a storyline starts, say, the one with Ed living with his sister, what would be the impetus?

BROWN: I had to have a wife for the guy who is in the operating room, that guy Bick. I wanted someone to have taken him there, and to take him home — if he had been taken home. A wife. Then I drew the character, and after I’d drawn the character I realized, “Hey, it looks like Ed the way I’ve drawn her. So why not make her Ed’s sister?” You know, the ideas just kind of flow along like that.

GRAMMEL: Were these ideas worked out a page at a time or an issue at a time?

BROWN: It really varies. There are ideas that I come up with that will see me through two or three issues, or even more.

GRAMMEL: In the beginning. I know for myself, there were a lot of questions as to just how much planning was going on. “The Man Who Couldn’t Stop” seemed like such a self-contained, quirky little work, and then he became the catalyst for a major plotline.

BROWN: Well, in the case of “The Man Who Couldn’t Stop,” I knew that he was going to be the character that he became in the storyline.

GRAMMEL: You knew how he was going to fit into the later storylines?

BROWN: No, I meant that I knew it was going to fit into that next story, the Ed the Happy Clown story, but I didn’t know all about the other dimension and everything. That stuff came later.

GRAMMEL: How has the present Bick storyline progressed so far for you? Are the next few issues clear in your mind?

BROWN: Yeah, vaguely. I was thinking, you know, I want to have Ed kind of settled down in one place. Because I’ve been moving him around so much I just want to stay in one place for a little while. I had this idea of making her and Ed brother and sister so he had a reason to stay — he had family there. It kind of fits together there.

GRAMMEL: So you’re dealing with that issue and you’re not sure where it’s going beyond that?

BROWN: Uh... yeah.

GRAMMEL: In the beginning we’re dealing more with scenes than stories —

BROWN: Because I couldn’t work up the enthusiasm or the interest to do longer works. That one “Walrus Blubber Sandwich” [Yummy Fur #1] was actually intended to be a longer story. I wrote a script for it and if I’d drawn it the way the script said it would’ve been 20 pages or something. I got to the third page and I was saying to myself, “I have another 17 pages of this to do?” So I just had that flying saucer come down and kill the guy, and that’s the end of the story.

GRAMMEL: You said that “Walrus Blubber Sandwich” was scripted. Have you realized that that method isn’t for you?

BROWN: Well, it doesn’t seem to work for me. When I have something really plotted out, really planned, by the time I’m halfway through a story I’m bored with it, and I want to do something different. Often I’ll have a specific plan — “Yeah, I know where I’m going with a story” — and then half-way through I say, “No, I don’t want to do that. Let’s take off in this direction and do this instead.” To some degree just to keep myself interested in the work.

GRAMMEL: It seems like it’s so much easier for a novelist to change things. It’s such a concrete thing when you’ve drawn, printed, and published a page. You ‘re stuck with that reality. The fiction writer can go back and change a scene from summer to winter, or whatever.

BROWN: Well, I’m not afraid to do that before something is printed. After it goes to the printer that’s it, of course. I’ll be almost finished a story and realize “I don’t like this character. I want to change this character.” And I’ve gone back through an entire story and redrawn the character in each panel that he or she appears in.

Well, I only did that once, so it was a she. But I’ve done that other times, too — changed things. You reach a certain point and you realize it isn’t working the way it’s going, so you go back and change something or throw something out. There’ve been times where I’ve finished pages and I said, “This isn’t going in the direction I want,” so I just have to scrap it. Which always annoys me, but I don’t feel that if I’ve done it I have to stick with it. Until it’s printed.

GRAMMEL: Do you consciously work at bringing old characters back into the storyline as with the aliens in issue #15 and Frankenstein in #16?

BROWN: Nope. Whatever seems to work at the time.

GRAMMEL: In re-reading the issues I noticed that you start off many issues with a flashback, but in the flashback you add things. Say, we see Chet killing Josie again, only this time we see that Ed has ended up nearby in the same forest. Since I’ve seen this pattern repeatedly I’m curious if this used to change things that you hadn’t planned.

BROWN: Yeah, definitely. When I first did issue #4 I didn’t know that Ed was over in the bushes a couple feet away. So, yeah, I’m adding and changing as I go along. As much as I can.

GRAMMEL; Have you ever had an idea that you really wanted to pursue but you couldn’t because of what had already been serialized? Something that even with the use of flashbacks, you couldn’t get around what was published?

BROWN: Never really a major idea. I think anything I can just about get around. I have some regrets. There are story ideas that I think, “Oh, it’s too bad that’s that way; I’d like to use that character in this way now.” But nothing really major.

GRAMMEL: I’m often reminded when reading Yummy Fur — something I don’t get from other Canadian cartoonists — that you are Canadian, that your references are Canadian. Is this deliberate?

BROWN: That just seemed the natural thing to do. I am Canadian. Why set the comic book in the U.S.

GRAMMEL: Did you ever find yourself unconsciously doing that because so much of what you’ve read is set in the U.S.?

BROWN: No, usually when you’re doing this kind of stuff it’s somewhere in some kind of imaginary place, and it’s just kind of vaguely North American. That’s how most of the stuff was done. It was only when I brought Ronald Reagan into it, then I actually had to decide where in North America it is taking place. And it just seemed the natural thing to do. I’m Canadian; it’s set in Canada.

GRAMMEL: But you didn’t use Brian Mulroney, you used Ronald Reagan.

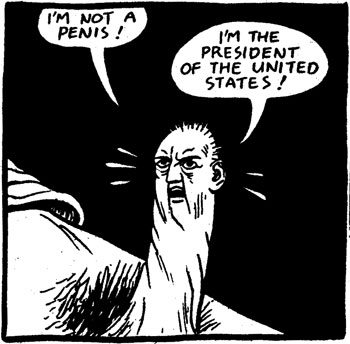

BROWN: OK, the truth is when I first got this idea for having a head on the end of someone’s penis, it was going to be Ed Broadbent on the end of Ed’s penis. Now, you don’t know who Ed Broadbent is, right? He’s the leader of the New Democratic Party in Canada. In Canada there are three major parties. There’s the New Democrats, there’s the Liberals, and there’s the Conservatives.

Brian Mulroney is Conservative. So when I was doing Yummy Fur I was thinking, “Well, do I want to put Ed Broadbent?” You know, no one in the States is going to know who Ed Broadbent is. “Who is this guy?” It’s just going to be a name to them, right? So I did go with Ronald Reagan. It makes me feel kind of embarrassed now, because it does seem like kind of a compromise. You know, maybe I could have put some kind of explanation in the back of the book or something, “Oh, this is who Ed Broadbent is.”

GRAMMEL: Why would you want Ed Broadbent on the end of Ed’s penis?

BROWN: I don’t know. I thought it’d be funny.

GRAMMEL: Is he a right-winger?

BROWN: No. He’s a… He’s quite left-wing. I never have really liked him. He’s always been kind of scrappy and abrasive. Not that I mind scrappy and abrasive. Actually, The Comics Journal is kind of scrappy and abrasive. I guess it depends on the way you come across. But no, I’ve never really liked him, even if he was promoting things I believed in. And actually, in the last election — probably in the last couple of elections — I voted N.D.P. despite their leader.

GRAMMEL: That’s interesting. I would’ve assumed that he was —

BROWN: The same kind of political –

GRAMMEL: Similar to Reagan.

BROWN: No, he’s not.

GRAMMEL: So it was pretty much just a personal attack. [Laughter.]