UNIONS AND HEARINGS

GROTH: Did you hear any talk in the ’50s about trying to start a union far comic artists?

INFANTINO: Yeah, but that was much later I believe.

GROTH: Really? Gil Kane told me that Bernie Krigstein tried to start a union sometime in the ’50s.

INFANTINO: The only one I remember was trying to be started by Arnold Drake. I know he gathered a bunch of people together and he said he was going to represent everybody. Now, the story goes — and you have to understand this is not first-hand — that he made an appointment with [Jack] Liebowitz, who was the owner of the company at the time, and supposedly he said to Liebowitz that they were going to begin a union, and we’re going to have everybody join and set prices. Now I understand that Liebowitz said to him, “Fine. You get everybody else in the industry to join, then I’ll join.” Which killed them because Marvel said the same thing. That kind of withered on the vine right there.

GROTH: When would that have been?

INFANTINO: That was just before the big Batman craze.

GROTH: Around ’63 or ’64?

INFANTINO: In that area. Again, this conversation is what I was told, I don’t know if it actually happened. But I do know that the wind went out of the sails after that meeting with Liebowitz. It was a clever thing for Liebowitz to say, you know? Because they’d go to the other place and they’d tell him the same thing — they’d all play the same game. Whether it was collusion, I don’t know. Then later on, Stan [Lee] and Neal [Adams] tried to start something, didn’t they?

GROTH: I understand that Stan Lee and you were involved in starting a professional organization?

INFANTINO: No, no, no. They started this thing, and I was there at the first meeting, Stan, me, Neal were there... And they wanted me to run for president: I said, “This is silly! First of all, I’m management. I don’t belong in this thing. I don’t think it’s wise or fair. I’m pulling out. I can’t be a part of this.” But Stan insisted on saying, “I’m staying there,” and of course he became the first president. But that didn’t do the boys any good — he was management!

GROTH: So it was a Guild that turned into a kind of social circle.

INFANTINO: That’s what it turned into, didn’t it? I still think what I did was valid. You can’t wear both hats — I don’t care what the hell they were saying.

GROTH: Was there much awareness among artists in the ’50s that a union would be helpful, or did they not care?

INFANTINO: They talked it up. They talked about getting wages and getting benefits and all that sort of thing. They even tried to get a hold of somebody from the AFL-CIO. But they considered the business too small to be bothered. That’s what I heard. So that’s why that all went by the boards.

GROTH: It would have been virtually impossible to do at that time, I should think.

INFANTINO: I think so because it was not a healthy business at the time. It was struggling.

GROTH: How did you personally feel about the Kefauver hearings? Did you feel there was any legitimacy there, or did you think it was a witch hunt?

INFANTINO: Well, the stuff that Biro and Wood were doing [crime titles]... It was pretty rough stuff. And what Bill [Gaines] was doing wasn’t very nice, either. You see, Kefauver was going to run for president. That was his whole thing, he needed a hook. And he found one. Here’s this weak business that’s just sitting there, and he moved in like a dog. So I think some of it was meaningful, but I think a lot of it wasn’t. They really went out there and attacked.

You know they’re playing the same game now with television. Only television can fight back. Things got so hot and heavy with Kefauver, the publishers got together and started the Comics Code [Authority]. They put this guy in charge, there was this big fanfare, they said there would be no more blood and no more this and that. Apparently this appeased some people. So comics very quietly went back on the stands. But they reached a sales level, and they left a bad taste with parents. Things were that bad.

Then of course when the guy bought Batman for TV, it blew the whole thing apart. Well, no. I’m wrong because The Flash kicked it off. I forgot about that. I was on the third Flash when they told me that the first one sold like hell. So Julie said to me, “You’re going to be doing a lot of these.” Also they were getting ready to put The Green Lantern out, and the whole goddamn family of superheroes. They were dragging these things out of the woodwork one after another.

GROTH: Up until the time The Flash came out, there were a few superheroes, but very few.

INFANTINO: Superman and Batman were around. I believe Wonder Woman, too.

GROTH: But The Flash is generally attributed to —

INFANTINO: That kicked it all off again. That was the one that started the whole ball rolling again.

GROTH: Now how did you feel about that insofar as you didn’t care for superheroes. Were you just happy to be working?

INFANTINO: I was just happy to work.

I WAS NEVER A FAN

GROTH: A few years after you did The Flash, you were given Adam Strange.

INFANTINO: Yeah, but I didn’t begin that strip. I was overseas running around with the [National Cartoonist] Society. I was supposed to start it off, but Mike Sekowsky started it because I was overseas. And when I came back, Julie says to me, “You’re going to be doing Adam Strange now.” I said, “Good, so we’ll be getting rid of the other..,” “No, no, no. You’re doing both.” So I said, “OK, great.” So I was doing Strange and Flash. Then shortly after that, Julie called me in, and I said, “Let me just finish this job I’m doing,” I think it was Adam Strange. And Julie said, “No, you better come up before. Irwin wants to talk to you.” Irwin Donenfeld was the editor-in-chief and publisher on that end in those days. So I went in, I went with Julie, we sat down, and that’s when they told us that Batman was in terrible shape. He said to me, “I’m going to give you six months on this thing. If you can pull it out, fine; if not, we want to drop it.” Isn’t that amazing? That’s how bad it sold. So they worked it out so that I would do every other issue, and all the covers.

GROTH: Is that what was called the “new look”?

INFANTINO: Right.

GROTH: And you slightly redesigned the costume, right?

INFANTINO: Yeah, but that wasn’t my idea, that was Julie. I had nothing to do with that.

GROTH: Who was doing Batman at the time?

INFANTINO: Bob Kane. But I understand — and I’ll never know for certain, I can’t prove it — that he had a lot of helpers doing this stuff. I think he was farming it out. And the stuff just wasn’t good.

GROTH: So they essentially just took it away from Kane.

INFANTINO: No, after I became an editor, I said to Kane, “Listen, Robert, here’s what I want to do... What is your page rate? I know you’re farming this stuff out. So I’ll give you half of the page rate, you don’t have to do a thing, I’ll take care of the rest.” And he went for it. And that’s how I started to put some decent people on Batman.

GROTH: When was this?

INFANTINO: That was when I was editor.

GROTH: So around ’67.

INFANTINO: Yeah, something like that.

GROTH: I think you took over the book in ’64— and at that time you weren’t the editor.

INFANTINO: No, I was just working for Schwartz.

GROTH: So who wrote the stories then?

INFANTINO: I think he had a bevy of people doing it. He said to me about Detective Comics, “You better come up with some ideas for covers. I want something different.” So, do you remember the first one? It was a departure. It was the one that was a three-panel thing. It was a little different, so they went for it. And the numbers started to move up then. Batman was coming back.

GROTH: Was Bob Kane still involved in the character?

INFANTINO: He was doing the Batman book, the interior. And I was doing the covers. We noticed that the Detective ones that I did would jump much higher than the Batman ones. But with the covers, I was helping that thing along, too. I don’t know if it was my covers necessarily — I think anybody’s covers would have been better than what was happening, frankly. [Laughter.]

GROTH: Did you enjoy doing Batman?

INFANTINO: I never enjoyed it, I was never a fan of that thing. But I wasn’t a fan of Flash either, so I don’t know what that tells you. [Laughter.]

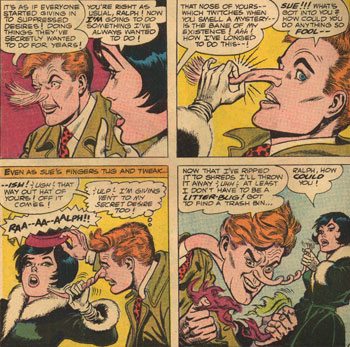

GROTH: At some point around this time, you also started doing The Elongated Man.

INFANTINO: Yes, I believe that character came out of The Flash, didn’t he?

GROTH: It was a backup strip in Detective.

INFANTINO: Is that where it was? Well, you would know best, Gary.

GROTH: I think I have you on record as saying you enjoyed doing that strip.

INFANTINO: That one I liked. You know why? Because it was almost comical. I enjoyed comedy.

GROTH: That is, in fact, one of your favorite strips, isn’t it?

INFANTINO: Yes. And that was the reason for it. It’s almost an animated version.

GROTH: Did you like Jack Cole’s Plastic Man?

INFANTINO: Oh, very much. I loved it. He was a great artist.

GROTH: Because obviously The Elongated Man is in that family.

INFANTINO: But I don’t know why he didn’t just bring Plastic Man back instead of creating The Elongated Man.

GROTH: True, because DC owned Plastic Man.

INFANTINO: Right. But you know what? Every time we brought back Plastic Man, it wouldn’t sell. The reason I think — I don’t know for certain, but the only thing I can point my finger on, is because it’s too humorous. And the kids wanted their superheroes very straight. That’s the impression I got.

GROTH: It’s true.

INFANTINO: And I had a guy doing it, Bob Oksner, he did the first couple. They were great when he did them. It was as good as Jack Cole, you know? But the damn thing would not sell.

GROTH: That was later in the ’60s?

INFANTINO: Yeah.

GROTH: Is Julie the one who gave you the Elongated Man strip?

INFANTINO: Yeah.

GROTH: This was one of the few times you were allowed to ink your own work.

INFANTINO: Yes, but they weren’t crazy about it.

GROTH: Julie especially, I assume.

INFANTINO: No, he didn’t like it at all.

GROTH: So why were you allowed to ink your work this time?

iNFANTINO: Because maybe I insisted. [Laughs.] Every once in a while I’d say, ‘“Julie, I’m tired of just penciling; I want to do something else.’’ He said, “Well, we won’t give you any main features to do. [Laughs.] So play with The Elongated Man if you want.” So I’d do those once in a while, and I’d also do The Space Museum, too. Do you remember that? That one I liked.

GROTH: This is something I don’t quite understand: Julie apparently didn’t like your inking very much. But really, what difference did it make to him if you inked your own work, or Joe Giella inked it or somebody else? I mean, what conceivable difference would it really make?

INFANTINO: The only thing I can assume is, there was a look in those days; they liked the very clean, sleek, sharp look. You know that shiny look of Giella. Kind of like the Dan Barry Flash Gordon, that kind of look. That was the kind of look they associated with DC.

GROTH: Yeah, Murphy Anderson.

INFANTINO: Right. Very clean, very sharp. Now my stuff looked like my penciling, very scratchy. And it probably irritated the hell out of him. [Laughs.] That was the reason, I think. So my inking was not the vogue of the day. It’s pretty obvious when you see it — it was so contradictory to everything else that was there. In fact when I did it, I used to sign that stuff, “Rouge Enfant.”

GROTH: [Laughs.] Is that right?

INFANTINO: It’s my name in French. [Groth laughs.] And I’d spook people up a little bit: On The Space Museum I’d sign some of them, “Cinfa.” So they’d get letters and they’d say, “Who are these two guys you got there? Who’s the guy named Cinfa, and who’s the other guy named Rouge Enfant?”

GROTH: [Laughter.] And why do they draw like lnfantino?

INFANTINO: Yeah! One of them used to complain: “The guy’s copying Infantino! What the hell are you using him for?” [Laughter.] I don’t think Julie answered them at the time. I think eventually he told them.

GROTH: Now Space Museum was written by Gardner Fox?

INFANTINO: I think so.

GROTH: Can you tell me who wrote Adam Strange?

INFANTINO: I think Gardner wrote that too.

GROTH: And Elongated Man?

INFANTINO: I believe that was John Broome at the beginning. John did those Detective Chimp stories [as a backup feature in Rex The Wonder Dog] that were so charming. You remember those? Those were John Broome; he was such a delightful writer. I loved his writing.

GROTH: Did you get to know him?

INFANTINO: Sure. He looked like Gary Cooper. He slaved over every word, that John. And it took forever to get a script out of him, but what you got was meticulous. Then I understand that later he went to Japan and was teaching over there. And that was the last I heard of John.

GROTH: So he escaped comics.

INFANTINO: I think so. I don’t think his heart was ever really in it.

GROTH: How was Julie as an editor at this point?

INFANTINO: He would leave me alone, frankly. He’d give me a script and he really wouldn’t bother me; just hand me a script and that would be it. Only once, it was at the beginning, I brought something in that I was very proud of, and I asked, “What do you think?” He looked at me and he said, “You’re getting paid for it, you’re a professional. What more do you want?” And that was the end of that! [Laughter.] I never asked him again. And he had a good point when you think about it. [Laughs.] He wasn’t much on giving out applause. He felt that was your job, which was true, actually.

GROTH: Now in ’64, ’65, you were about 40. Was your enthusiasm for comics waning?

INFANTINO: I don’t know, we didn’t see each other much. I didn’t see the boys or Alex much, or Joe, or Frank. I think we all kind of moved into our own directions. So I would go in to drop my stuff off, and then just go home. I’d have my own group of friends — none of whom were in comics. And I think with the other fellows it was the same thing, if I’m not mistaken. So we all kind of went our own way.

GROTH: Can you explain why you think that might have happened?

INFANTINO: I don’t know. I’m only realizing it now that we’re talking about it. I guess we were trying to develop different associations. There was no animosity amongst anybody; we all liked each other. In fact when we’d see each other in the office, we were very friendly, sometimes we’d have coffee, we’d kid around for 10 or 15 minutes, and that would be the end of it.

GROTH: It sounds like it had become a job.

INFANTINO: Pretty much. For me, anyway. I can’t speak for the others. But for me it had.

GROTH: It seems to me that there was a big period in comics, from the late- ’40s or early- ’50s to the mid- ’60s, when new artists didn’t really come into the field.

INFANTINO: Well, DC was like a closed shop. And you just couldn’t break through. I’m sure many people came up and nothing happened.

GROTH: That’s interesting, because there were a lot of people who started off at roughly the time you did; I assume that Curt Swan must have been around your age...

INFANTINO: Curt was there. He worked for Mort Weisinger, he did Superman only. Mort had his own group of artists on Superman. He was running the show there; he could take anybody he wanted, and they could only work for him. He was a prima donna. But no matter what anybody says about Mort Weisinger, he was a hell of an editor. If you read the Superman stories from those days, they were good stories. So you can’t sell the man short.

GROTH: You never worked with him, right?

INFANTINO: Once or twice. He wanted me. But I couldn’t do any more — I was doing The Flash, I was doing the Batman covers, I was doing Adam Strange — and he asked [Irwin] Donenfeid and Donenfeld said, “Where’s he going to jet another hand from?” And those books were doing well, they were taking off... In fact they even had me doing the Batman strip in those days.

GROTH: The newspaper strip?

INFANTINO: Yeah. Then finally I went to Donenfeld, and I said, “Listen. You got to take me off something, I just can’t keep doing all this.” So he took the strip away. He said he would rather see me on the books.

GROTH: So even though you may not have been quite as excited as you were drawing, you must have been making a very good living,

INFANTINO: In those days I was making about $18,000 or $19,000 a year. [Laughs.] Which wasn’t that great, but I guess at the time it wasn’t too bad.

GROTH: Well in the early-’60s, the value would be at least twice what it is now...

INFANTINO: Oh, more than that.

GROTH: That wasn’t bad.

INFANTINO: Not bad.

GROTH: So you must have considered yourself successful.

INFANTINO: Well, I was working — that was successful! I mean, we weren’t starving, don’t misunderstand me. All the boys had a car and we were running around a lot, so yeah, I would think so.

GROTH: Where were you living at this point?

INFANTINO: I think in the Village.

GROTH: You wouldn’t have had a car in the Village, would you?

INFANTINO: No, you’re right. I was living at home with the folks in Queens. Then I got rid of the car, and I moved into the city. That was much later, though.

GROTH: So you lived in Queens for a long time.

INFANTINO: Yeah. It was like suburbia, like L.A. Everybody had a car.

GROTH: Would you come into the office once a week?

INFANTINO: Right, once a week I would drive in.

GROTH: Drop your stuff off and —

INFANTINO: Pick up another script. I’d have lunch with Julie in some donut factory or something. [Groth laughs.] And he only had soup. That’s all he had, every day. Then I’d leave and go home. And I’d come back the next week. This routine went on for years and years. What his relationship was with the other fellows, I don’t know. As I said, when I was there, nobody else was there. So I wouldn’t know what the hell went on.