DECLINE AND DESIGN

GROTH: Can l ask you to describe the decline of superheroes? I mean, evidently they just faded out.

INFANTINO: They didn’t fade out; Wertham was in, and there were the Committee hearings, and they had Bill Gaines in, he was doing the horror comics at the time, and I thought he thought he was being funny at these Congressional meetings, but I understand Bill was on Valium every day there. And apparently they took offense to some of the things he said. I’m not clear on that because I don’t remember following that thing. But there was no television in those days. I don’t think there was, was there?

GROTH: Well, it must have been televised, because I’ve seen a clip of Bill Gaines testifying.

INFANTINO: That could be. I don’t remember that. But right after those hearings, the business took a nosedive, I mean, really bad. His books were thrown off the stands completely, and the only thing he was left with was Mad magazine. And there was a whole story on that one.

GROTH: Let me try to nail you down on this, because it’s my impression that what Wertham was going after was horror and crime, and I think that superheroes started declining before then. In fact, publishers were getting into horror, crime, westerns, and other things precisely because of the decline of superheroes.

INFANTINO: Yes, that’s true. They were doing science fiction too, at the time. But it wasn’t a sharp descent; superheroes just started to slip away, little by little.

GROTH: Do you. remember what you were doing during that terrible, censorious period with the Kefauver hearings, around ’53, ’54?

INFANTINO: All of us were doing a bunch of Westerns, romance, science fiction — we were just trying to get something to kick off, you know? Gil [Kane] was doing Rex the Wonder Dog, we did a lot of romance books, I did Pow Wow Smith and The Trigger Twins, and a number of science fiction things. But none of it sold very well. The business was wounded pretty badly at that time. They [Senate Committee and Wertham] did a number on us.

GROTH: How did you feel about that at the time?

INFANTINO: We got hurt financially because the people at DC called us all in and told us we were going to have to take a page-cut. I believe it was a $2 or $3 page cut. Of course we were a little horrified by it. But they said it was either that or nothing. The company had to save some money because they were getting beaten up. And they saved a hell of a lot of money that way actually — two bucks on every page, that’s a lot of money.

We did it because the sales were not good at all. And the books were just about keeping their heads above water. So that’s how we floundered along.

GROTH: I know you worked for St. John between ’50 and ’53.

INFANTINO: You could be right. And I worked for Simon and Kirby at one point, I did Charlie Chan for them.

GROTH: I thought you did that for Dell.

INFANTINO: No, no. That was for Simon and Kirby. Crestwood. They called me up one day and asked me to come over, they’d like me to do some stuff for them. That was for Simon and Kirby, in the ’50s. Maybe a little earlier. The reason I did it, because the pay wasn’t that great, was because I wanted to work with Jack. I wanted to learn from and study Jack. So I went there and I worked with Jack, Mort Meskin, and Bill Draut. Three brilliant guys. I learned an awful lot from them. I didn’t quit DC by the way. I’d go home and do my DC work at night. [Laughs.] And I’d go to Simon and Kirby’s during the day and work there. Now, I did this for, oh my God, nine or 10 months, then I couldn’t handle it any more. I wasn’t sleeping any more. So I told Simon and Kirby, and they understood. I left and went back to DC.

GROTH: Can you tell me how Simon and Kirby split up their functions? Who did you deal with?

INFANTINO: I can tell you when I was there, Joe would hand me a script, and I would draw it. As far as how they worked, I don’t know.

GROTH: But it was Joe who would coordinate the scripts?

INFANTINO: Yes. And I saw Jack writing copy all the time, too. Now, he’d draw the things, but beautiful, the artwork was just incredible. But it had to be scripted because even Mort would get a script, but he’d draw his. Jack would draw his. And I think Simon went back later and he’d correct the stuff. Now, he had writers working there for him at that time. There was a guy named Jack Oleck.

GROTH: Was this the first time you would have met Kirby?

INFANTINO: No, Frank and I used to go up to Tudor City as kids, and we would bother him up there, and watch him work. He was very sweet.

GROTH: Would that have been at the Eisner studio?

INFANTINO: No, they had an apartment, Joe and Jack, when they were doing stuff for, I think it was DC at the time. We’d go up and Jack was always terrific with us. He was always kind to anybody around him. He always had time for people. He was delightful. Very sweet. Very helpful. Anything you asked of him, he’d help you with. I’ll give you a real thing on Jack: I did a shot of a guy hitting a woman. I showed it to Jack and asked what he thought. He says, “No. Here, do this. Do the scene, but don’t show the people. Just put the shadow on the wall. Let the imagination take over.” I did it, and Jesus, it worked like hell. So you can see the way he thought. He helped me tremendously. I even did a strip for him one time. Only, he wrote it and l drew it.

GROTH: Really?

INFANTINO: It was a Western. I don’t know what the hell happened to it. We tried to sell it, and nothing happened.

GROTH: Was this a newspaper strip?

INFANTINO: Right.

GROTH: Was Jack universally admired back then?

INFANTINO: Oh yes. Always.

GROTH: Because it sounds like there was sort of a pantheon back then: Mort Meskin, Lou Fine...

INFANTINO: ... Eisner, Caniff, Raymond, Foster. Yeah, yeah. I got along well with Mort, too. I learned an awful lot from him.

GROTH: He was older, right?

INFANTINO: Yeah. Mort was a strange man. But very talented. His work had a nice, delicate flair to it. While Jack’s was powerful, Mort’s had a subtlety. In Mort’s work, people were pretty, you know what I’m saying? They were just lovely. I found out later that when I met him, he too was a fan of Ed Carder. I was very surprised. Then when I looked at his work, I could see the resemblance. Mort was a lovely teacher, and a nice man. But then I had to get back to DC because I was really losing money working for them. [Groth laughs.] Well, not so much that, but I was working there in the day and doing my DC work at night. And I just couldn’t keep it up, it was just too much. So then when I went back to DC, I started going to the Art Student’s League at night.

GROTH: And you were studying?

INFANTINO: Figure drawing. Then much later went to the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Queen’s College at night.

GROTH: So you went to school it sounds like, all through your 20s.

INFANTINO: Oh yeah. I think most of the boys did, didn’t they? Alex and Joe?

GROTH: Well, I’m not sure. My impression is that a lot of the artists back then were basically self-taught.

INFANTINO: Well, I can’t say that. I learned so much from Jack and Mort. Whether they admit it or not, I think they all studied someone.

GROTH: What I actually meant was that the process was more an apprenticeship than going to formal art school.

INFANTINO: Oh, yes. But there was a point — for me anyway, I can’t speak for anybody else — I felt I had to get to school. I just felt there was something missing, and I had a wonderful teacher at the Art Student’s League, a guy named [John] McNulty, I’ll never forget him. He was a genius at composition. He taught me how to compose. I’d go there three or four nights a week; two nights I’d go with McNulty, and two nights I’d study figure drawing.

GROTH: You once said, “I’m basically a designer. If you look at my work, you’ll see the anatomy is never correct.”

INFANTINO: I know. I should have said “totally” correct. What happened is, after I learned the anatomy, I threw it out. So go figure that one. I felt you didn’t need it. Designing was the key, I felt. But that was my thinking.

GROTH: By “designing,” you mean the composition within the panel?

INFANTINO: Right. The use of negative and positive shapes: All the shapes in the panel had to mean something. So, to me, if the shapes didn’t draw the eye in, then they weren’t worthwhile. You had to move the shape and change the shape to make it work for you. So that’s what I did.

GROTH: Alex [Toth] certainly eventually must have felt the same way.

INFANTINO: I can’t tell you how Alex worked. For me, the figure was the most important thing. And nothing else in the panel mattered. But later on you found out that it was the total picture you had to worry about. So then I modified the anatomy in the drawing, and other things went to work for you. That comes from trial and error. But I became essentially a designer more than anything else.

That’s when I started studying the Impressionists of France. Degas was the king for me. I was into Degas like mad. The teacher at the Art Student’s League put me onto him. Once I understood him, I went nuts for him. He was a genius of design.

GROTH: Can you tell me how you incorporated your love of Degas into your own work?

INFANTINO: Sure. This teacher, McNulty, he would take a painting of Degas’ — do you remember “The Absinthe Drinkers”? That particular drawing, if you look at it carefully, you’ll see how the green table forms a V-shape that takes you right into the figure. And he had little spots of red around the figure, and everything worked in unison in his work, and the more you looked at it, the more you saw. So I says, “Mother-of-God, this guy drives me nuts.” So then the teacher explained how to take it apart and understand it. The more, I knew, the more I admired him. He was pure genius. You know, he was the master of that whole group of Impressionists.

GROTH: So you really studied him.

INFANTINO: Oh yeah. Actually I moved from the comics stuff into these Fine Art paintings. Because at one point I thought, how can these guys help me? There’s no way! But it wasn’t true. Because the more I studied them, the more I could apply what they did into what I did. So I learned more from them than anyone else.

HOPES AND DREAMS

GROTH: Can I ask you what your aspirations were at this point? I guess you’re talking about when you were still in your 20s.

INFANTINO: My biggest joy would have been to have a newspaper strip. And I never did. I never could conquer one. I tried. I did The Phantom for one Sunday page. And nothing happened. But you know why? Dan Barry’s brother had the inside track there, and he got the strip. [Groth laughs.] But that was understandable.

GROTH: And you also drew one week of Flash Gordon for Dan Barry,

INFANTINO: Oh, I did more than that. I did a couple of weeks of dailies for him. I did The Lone Ranger many, many years ago. Not too much, just a little. And I tried a couple strips of my own, but I just couldn’t sell.

GROTH: But you would have preferred a newspaper strip to comic books.

INFANTINO: Then, yes. Oh, I was trying constantly. But I just couldn’t make it.

GROTH: Why would you have preferred a newspaper strip?

INFANTINO: Well, they made a lot of money! [Laughter.] These guys made lots of money. And frankly, in those days, comic book artists were not respected. Newspaper strips were. And even then the Cartoonist Society — if you were a newspaperman, and you had a newspaper strip, you had respect. And I think the cartoonists and comic book guys were let in only because they needed the money.

GROTH: Right, they needed membership fees.

INFANTINO: Right. I just don’t think we got as much respect in those days.

GROTH: Is that because comics were just seen as trash?

INFANTINO: Pretty much. This is true because we would always be ashamed to tell people what we did for a living? So, what the hell? What else would it mean?

GROTH: When you were in your 20s, how did your parents feel about your budding career?

lNFANTlNO: They never said very much. They left me alone. But then I started traveling like hell. I worked very hard for nine months, and then I’d take off. I’d go to Europe, go to Asia, all over.

GROW: Is that right?

INFANTINO: I had to travel. I had it in my blood.

GROTH: That sounds like the life.

INFANTINO: Oh yeah, it was great. And when I’d come back, I’d start working again. I traveled with the Cartoonists’ Society too. They had the trip tours to Europe, to the Army bases, and in Asia. The Army would give you a GF-17, and they’d ship you over there to draw cartoons for the soldiers. I got commendations here from the Department of Defense and all that stuff. So I traveled quite a bit.

GROTH: That must have been great.

INFANTINO: Well I’ll tell you: it enhanced your work. Whether you believe it or not. It does so much for you to see other lives and other cultures.

GROTH: Would this have been the late-’40s?

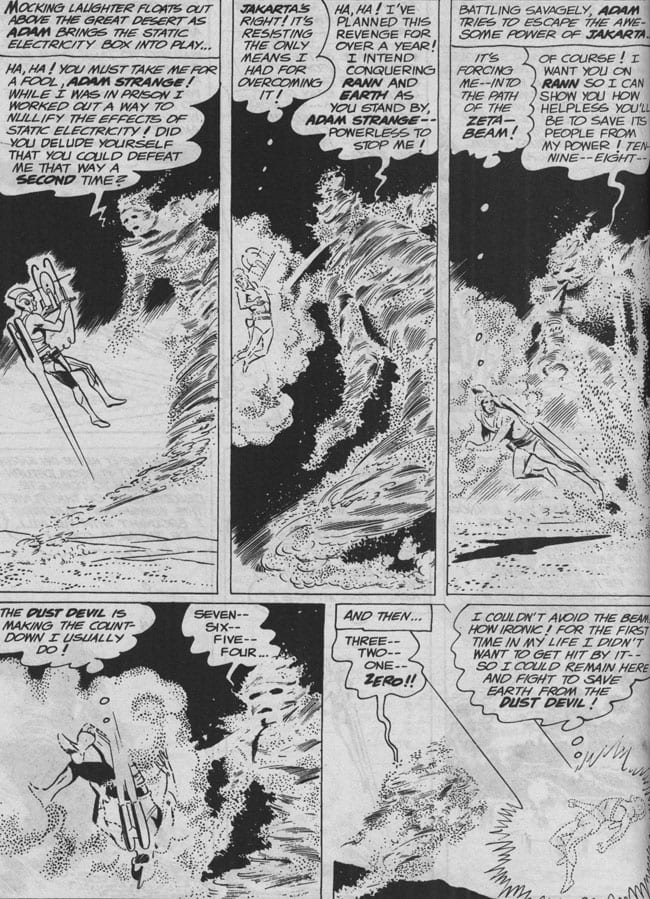

INFANTINO: Yes, and well into the ’50s. In fact at one period, I was supposed to do Adam Strange, and I was away, so Julie had Mike Sekowsky do the first one. And when I came back, he gave it to me. But I was supposed to start the thing, and I was away. I pick up with Adam Strange in Mystery In Space.

GROTH: It sounds as though you were able to make a comfortable living.

INFANTINO: Oh, yes. But it wasn’t great money in those days. We were getting something like $30 a page for penciling.

GROTH: When would this have been?

INFANTINO: When I was going to leave DC, I was getting about $30 or $35 a page. And I was going to go to Marvel at that time because they were up to go to work for them. So I was making about $18,000 a year.

GROTH: This was in the early-’60s?

INFANTINO: Yeah. I was doing covers and stories at DC.

GROTH: Eighteen thousand dollars a year was pretty good then.

INFANTINO: It was good, yeah. But Stan Lee called me and offered me about $23,000. $5,000 raise.

GROTH: And you turned that down.

INFANTINO: Well, Irwin Donenfeld, who was the editor-in-chief there at DC, asked me to become the art director. And I thought that was more fascinating. And that’s when I left drawing.

GROTH: Didn’t he ask you to become the editorial director?

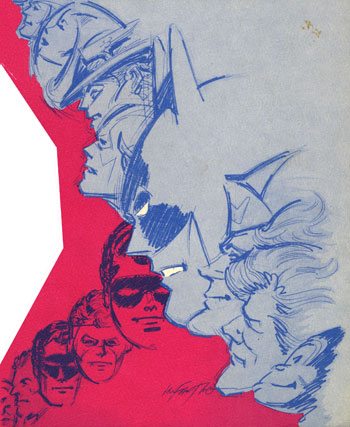

INFANTINO: No, first the art director. Because they were getting creamed by Marvel. At some point, I would create covers and Julie would write stories around them. So I’d be doing Batman covers, Flash covers, and apparently the stuff I did was selling. So he felt, why not do this for the whole company? Design all the covers?

GROTH: This would have been the mid-’60s.

INFANTINO: Right.

GROTH: Let me skip back for a moment. You mentioned getting the Flash assignment from Julie Schwartz in 1956. Since that really started the regeneration of superheroes, can you tell me a little more how that came about?

INFANTINO: I went in one day and without fanfare or anything, I brought a job in, I think it was a romance job, and Julie said to me, “You’re going to do a superhero again.” I wasn’t particularly keen on it frankly, because I didn’t enjoy them. He said, “We’re gonna try the Flash.” I said, “Not Flash” [Laughter.] Bob [Kanigher] handed me the script, and even laid out the very first cover. He did a rough drawing of it; I’ll never forget it. Then he sat with me and asked, “If there’s anything in the script that you don’t quite understand, ask me.” And we went over it a little bit. That’s how I know it was definitely Bob Kanigher who wrote the script. He introduced the thing with the ring with the uniform coming out. If you look at the very first script, it was a Kanigher-type story, you know what I’m saying? He had a flavor to his stories that were distinctly his own. Whether you liked them or not, it was Bob Kanigher.

Then Kanigher told me to go home. By the way, Kanigher was very good to work with — he gave you lots of license. He said to me, “Go create a costume for this guy. Forget the old costume, that’s passé. You go create something.” So I went home and designed this thing that you see today. And it works because it’s so simple. And they all liked it and said, “O.K., let’s go with it.” And that was it.

Now, I brought that one in, and I believe we didn’t do a second one immediately. They put me on a science fiction job and something else. And then they tried another Flash. I don’t know what the politics were, but Schwartz had somebody else did it, not Kanigher. I think it was Gardner Fox, or John Broome. But in those days we didn’t question. We kept our mouths shut and did what we had to do. But Bob was off it suddenly. If there was something [going] on between those two, Julie and Bob, I don’t know what it was.

GROTH: Kubert inked the first one, didn’t he?

INFANTINO: Yes.

GROTH: Kupert seems like an odd choice to ink you.

INFANTINO: Yeah. I have no idea why they picked Joe, but he was chosen.

GROTH: I assume that back then the editor would choose the inker, and you would have nothing to say about it.

INFANTINO: Absolutely. I had nothing to say.

GROTH: Could you object to an inker?

INFANTINO: No, in those days you couldn’t object to very much. We just wanted to work — it was scary in those days. The business was in the throes of the terrible Kefauver thing, and we used to even be ashamed to tell people what we did for a living, it was so bad. So we kept our mouths shut pretty much, we took the pay cut, and we did what we could.