If there are any readers of action comics out there who don't recognize the name of Geof Darrow, they will definitely recognize his art. Manically crowded with bloodied chicken fat, yet unsettlingly legible—even whimsical—Darrow's pages read like deep-focus documents of fallen worlds caked with rubble and human debris. Plus: it's funny!

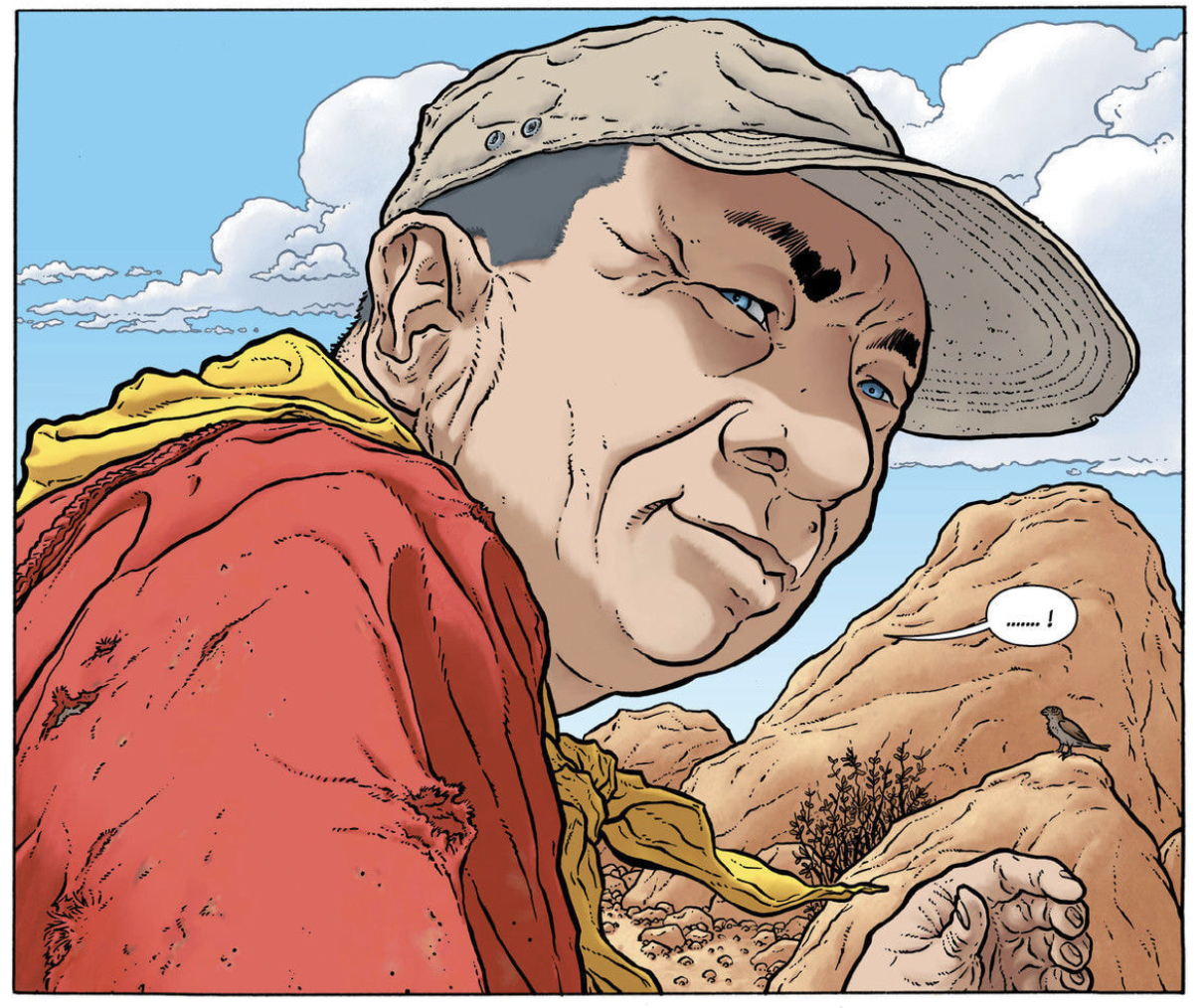

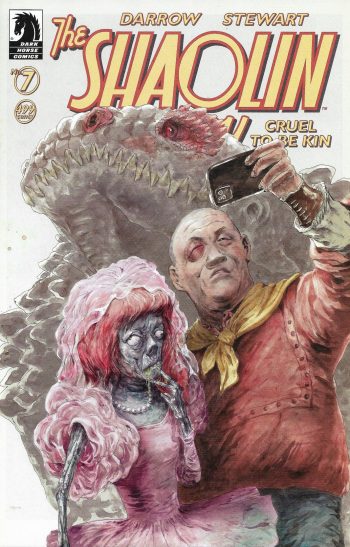

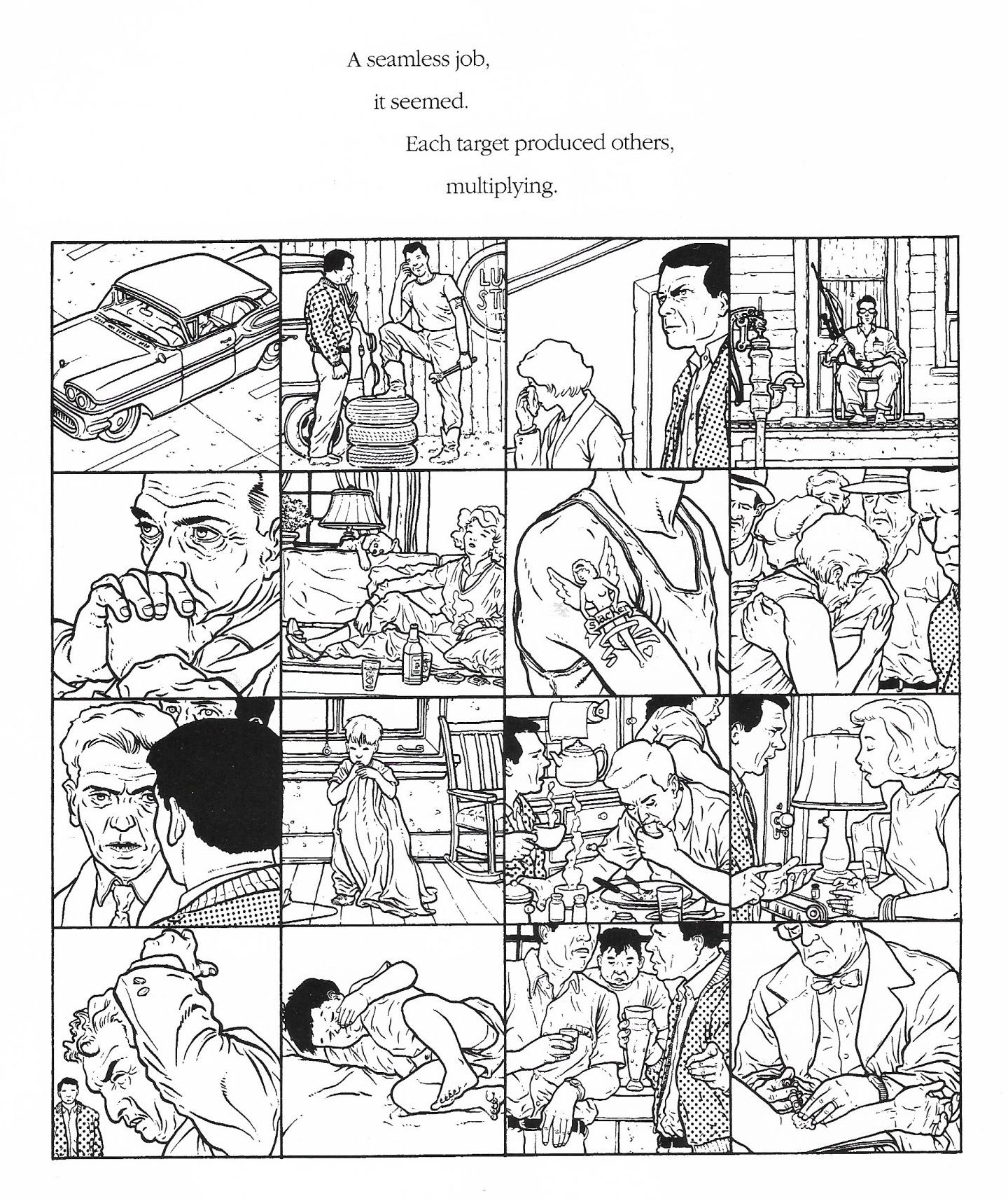

An animation professional first brought to prominence via a collaboration with bande dessinée legend Moebius on the illustration portfolio La Cité Feu ("City of Fire"; Ædena, 1985), Darrow build a small but striking body of work in French-language comics; the cult classic album Darrow Comics and Stories (Ædena, 1986) collected the adventures of unflappable Bourbon Thret, a master of combat wandering a world of aggressive popular culture. Americans, for the most part, didn't catch on until Hard Boiled (Dark Horse, 1990-92), an extraordinarily lively and bleak collaboration with comic book superstar Frank Miller, whose writing credit belies the latitude Darrow enjoyed in telling the story in visual terms. The pair collaborated again on The Big Guy and Rusty the Boy Robot (Dark Horse, 1995), a zany homage to Japanese tokusatsu media, after which Darrow found himself drawn into the orbit of Lana & Lilly Wachowski, supplying conceptual designs for their international blockbuster film The Matrix (1999) and its various sequels. It was through the Wachowskis' Burlyman Entertainment that Darrow revived Bourbon Thret as the Shaolin Cowboy in an eponymous comic book series (2004-07), though he later returned to Dark Horse, which subtitled the first series Start Trek in reprint, and released three additional miniseries: Shemp Buffet (originally published as vol. 2 of The Shaolin Cowboy, no subtitle, 2013-14); Who'll Stop the Reign? (2017); and the recent Cruel to Be Kin (2022), a collected edition of which will be published in July.

The following interview was conducted by Matt Seneca via Zoom in 2022; amidst the serialization of Cruel to Be Kin, Darrow proved resolute in his dedication to the act of drawing, and the necessity of challenging one's craft. The transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

-The Editors

* * *

MATT SENECA: So you started in animation at Hanna-Barbera, right?

GEOF DARROW: You mean in my art career? I started actually in advertising in Chicago.

Okay.

I worked at an audio-visual company. Companies would have these sales meetings and they would, for instance-- we did one for McDonald's. They find some nice location and they bring out the best sales reps and they wine 'em and dine 'em, and they probably pay for whatever. I think it's just an excuse to get the guys out of the city so they can be footloose and fancy-free. And then we'd do these slide presentations. When I say slides-- those things don't even exist anymore, but it was projected images on a screen, and it'd be like: "Why aren't we selling more fries? Well, we're gonna fix that right now!" And I would draw cartoons that would go along with it.

And then I got tired of that. Then I moved to Los Angeles and got a job.

Was animation a dream job for you? Or was it always comics as the end goal?

I always wanted do comics and, wrongfully, I thought, well, you know, I'll go out to LA and there's animation studios out there. I thought the Hanna-Barbera stuff was so bad they'd even probably hire a hack like me. And, I found out there's all these amazing artists working there. [Hanna-Barbera] just didn't have the money and, I don't think, the desire of the company to... it was just crank 'em out and make money and move on to the next thing. But man, the guys they had there, the talent they had there was just astounding.

A lot of guys trying to do the opposite of you, right? Leave comics and get a stable gig.

Yeah. 'Cause it paid well. I mean, there were a lot of comic guys there. That's where I met-- I met him at a convention, but I actually really met Jack Kirby at Hanna-Barbera. And there was a lot of Filipino artists who'd gotten into animation. It was Jesse Santos and Alfredo Alcala and Ernie Chan, just a lot of guys. Even Carmine Infantino was out there.

Wow.

In fact, he was working at Marvel [in animation], which was really odd, because it was him and Stan Lee. [There was] this conversation where Stan was standing there with Infantino, and Infantino says "Stan, how come you take all the credit for everything?" And Stan Lee goes, "well, somebody had to!"

Oh man.

But he was a really, really pleasant guy. They both were. I mean, gosh, the talent. Plus a lot of ex-Disney guys worked at Hanna-Barbera 'cause they paid better than Disney.

Did you talk with those guys about wanting to break into comics?

Oh no, no. I was too shy. I didn't, no. I gotta figure if they were there doing animation, they'd kinda had it with comics. Except for Kirby... he was just so fast, and he did character designs. He'd come in once a week, his wife Roz would drive him in, and he'd have a stack of drawings, and it was sometimes my job, and everybody's job, to take his drawings and make them animation-ready. 'Cause it's a different thing.

There's a lot more to do with animation, I feel, in some of the comics work you do. The time between panels is so short that it almost resembles key animation in a way. Do you feel like you learned stuff working in that field that you've brought into comics?

Actually, what I learned there was how little I knew in terms of drawing. My boss was a gentleman named Bob Singer. Really, really good artist. He was head of the model department - the models were people that we would do. You'd get a script, you'd have to go through and pick out new characters, if there's a monster or various things, cars and incidental characters you'd draw. You'd have to do models so the storyboard guys would have 'em to use. And when they were animated, you'd have a consistent [look]. I wasn't really thinking in three dimensions. When you're in animation, it has to be three dimensions, 'cause they have to be able to turn it [i.e., draw the character consistently from different facing sides]. And gosh, it was hard. A lot of the guys in the comics field, it was hard for them. 'Cause they could do that one drawing, but then to turn it, make it kind of three-dimensional.... Even Jack-- I mean, his stuff was really neat, but sometimes it was hard. You had to change it, because if they asked him to do a turnaround, he just did things so fast that the back would look nothing like what was on the front.

My boss was just always like, "did you go to school?" I'd said, yeah. "Whoa, you've got a lot to learn!" And he'd correct my drawings, and I learned to start to think in three dimensions, as opposed to faking things. You can't fake stuff, in animation it has to be able to be turned around. But I didn't do storyboards or anything like that. It wasn't my goal to work in animation. I'd wanted to do comics. And I thought, well, this would be a job where I'd work there in the summer. [Laughs] I was like the last guy hired, the first guy fired... I saved up my money from the first year I was there to pay for my trip to Japan, 'cause my dream was to go to Tokyo.

Did you end up getting there?

Oh yeah. I saved my money and I was on unemployment, and I found the cheapest flight I could, and I stayed in youth hostels and I was there for I think about two months.

Were you a fan of Japanese comics at the time?

That's why I went, yeah. I mean, I bought Japanese comics in Japanese. I couldn't read it, but the storytelling is so fantastic. I just love the drawings. At that point I was really into Akira Toriyama who, before he did Dragon Ball, he did a comic called Dr. Slump, which was really, really funny and just beautifully drawn. I liked Monkey Punch, who did Lupin III. And I liked [Gōseki] Kojima, who did Lone Wolf and Cub. And I discovered-- I think it was there I found [my] first book of [Katsuhiro] Ōtomo.

Right.

'Cause in those days you went to Japan, you could go in there and-- now everything, even over in Japan, the books are in plastic. Sometimes I'd go to the stores in the afternoon. There was this one comic store I'd go into, it was was nothing but manga, and it was full of kids. I mean, you couldn't move, and I'm not the tiniest guy on the planet, and they're all in there reading! It was like a library. So I'd have to go early in the morning before the kids got out of school, 'cause otherwise I couldn't maneuver. Now it's all in plastic. You can't read them like they used to.

I was also into woodblock prints and Japanese movies. I was trying to find movie posters, which was impossible at the time. But yeah, I did get there.

And then you ended up in France for a long time, right?

Yeah. I mean, I had met him [Jean Giraud, aka Moebius]... I was still at Hanna-Barbera, and he had come to work on Tron, and I don't know who I heard it from, but there was a rumor that Moebius was at Disney. And I was always talking about him from way back when, and I said, oh god! I happened to know-- my girlfriend at the time, one of her best friends' husband was a project manager at EPCOT Center being built in Florida, and he was working on the lot. I thought, oh, maybe he could get me on the lot and I can meet this guy. Getting on the lot at Disney was like trying to get into the CIA at that point. [Seneca laughs] So I called him up and I asked him, and he goes, "what's his name?" He didn't know who [Moebius] was. And he said, "well, I'll see if I can find him." And a few days later he called me. He said we're having dinner with him on Saturday night. I was like, holy smokes! Wow! I still didn't think it was him. I thought maybe it's some other guy.

And that's where I got to know him. He asked me what I did, and I said, well, I do comics. He goes, "really?" He said, "can I see what you do?" And at that point I was trying to figure out perspective, I was mostly doing vehicles and spaceships at Hanna-Barbera. I had some drawings on my board, and it was my crude attempt to draw things in three dimensions using perspective, as opposed to just faking it. And they looked really blocky and cubical, almost like the stuff in Tron, and he was like, "oh wow, you do computer animation design!" And I'm like, umm, yeah! [Laughter] But you know, I stayed in touch with him, and I saw him a couple of times before he left. I think he just didn't know anybody, so it was nice for him to-- I was just such a fan. And he took a liking to me, and my next big trip was to go to France. I did a comic story that I wanted to get printed in France, and he took me to Métal hurlant.

And that was Bourbon Thret [the short story "Terreur Paroissiale"]?

Yeah. Yeah, and they printed it. It was printed there. I moved back, and a couple of years later I thought, ahhh, I wonder what it's like to live in another country? And since I knew [Moebius] there, and I had met one of his other publishers-- they liked my work, and they said, "why don't you come over?" And also, there was a comic project that Mobius wanted me to draw. And so I moved to France at, like, the end of 1983 to work with him.

Was he your primary influence at the time?

Oh yeah. Him and, you know-- in the beginning, I guess my biggest influence was Jack Kirby, of course. The superhero stuff. There were a couple other artists. I really liked Sam Glanzman. He used to do this thing called Kona, Monarch of Monster Isle. God, I loved it.

Those are amazing comics.

I still love those things. That's one thing I would draw if somebody said, "can you draw?" Yeah, I'll draw Kona. That, and I liked Turok, which was drawn by Giolitti, Alberto Giolitti, and god, those guys-- I mean, Giolitti could draw likenesses, as he did Star Trek and all the westerns, he did Gunsmoke, and it looked just like-- he had the stills, but they looked like the guys. But then there was Kirby, then I went through Vaughn Bodē, big, big influence. And Richard Corbin was-- I mean, you can't see it at all, but gosh, those were the guys that I liked the most. Until I discovered through-- I was able to get the books through Bud Plant, 'cause he was selling French editions, and I'd seen a couple drawings of Lieutenant Blueberry by Giraud, and I sent for one of the books and I was just: holy smokes. This was in '73 or something.

So before Heavy Metal.

Oh, way before. It's funny, I always tell this story. I'd show this stuff to people, and they'd go "ahhh, I can't read it." Look at the drawings, for Christ's sake! Look at the drawings, I don't care if you can read it, just look at what these guys are doing! And then when Heavy Metal came out there were like "ooh, look at this guy in Heavy Metal!" Yeah, it's the guy showed you like five years ago and you didn't want to hear about it. [Laughter]

So you went out to France. Was it specifically to work on this comic project with Moebius?

Yeah. Which never materialized, because he was part of this crazy sect [that of Jean-Paul Appel-Guéry]. It was based on some story that this sect wanted him to draw, and I was gonna draw it and he was writing it, but they were so restrictive on what you could and couldn't draw. You weren't supposed to draw prehistoric creatures because they were impure. [Seneca laughs] And he said to me, "Geof, you know, I can't do this to you. I can't have somebody telling you what to do all the time." And so instead we did this thing called City of Fire. His publisher at the time was named Jean Annestay. He said, "why don't, Geof, you do these big drawings, and then [Moebius] will ink them?" [Darrow laughs] That's the only thing we really worked on together. That was my big entry into the European field.

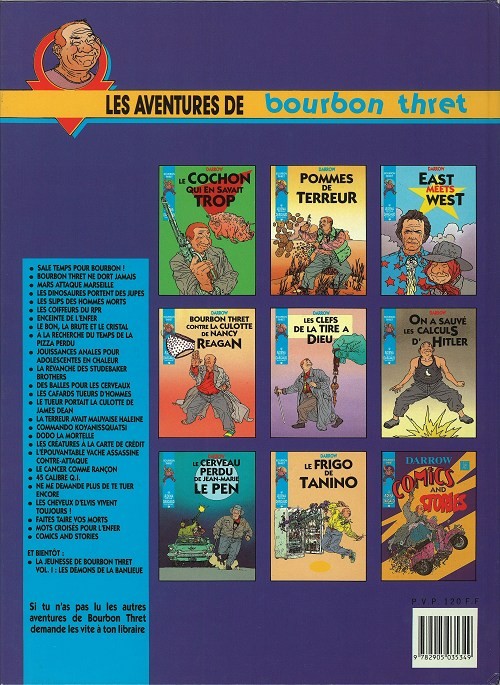

His publishing company [Ædena] ended up publishing a book of your comics after that, right?

Almost immediately thereafter, yeah. And because of the City of Fire thing, people kind of knew who I was. The big joke [of the book, Darrow Comics and Stories]-- I thought it was a big joke to make it out like I've been around forever on the back cover. I came up with all these fake titles for books that don't exist. And they kept getting orders for those books. [Seneca laughs] I thought it was funny. And I also did a thing if you bought the limited edition it came with Darrow Magazine. It was a magazine just about me. Just a big joke. But once again, some people thought it was a real magazine and they'd get submissions.

Almost immediately thereafter, yeah. And because of the City of Fire thing, people kind of knew who I was. The big joke [of the book, Darrow Comics and Stories]-- I thought it was a big joke to make it out like I've been around forever on the back cover. I came up with all these fake titles for books that don't exist. And they kept getting orders for those books. [Seneca laughs] I thought it was funny. And I also did a thing if you bought the limited edition it came with Darrow Magazine. It was a magazine just about me. Just a big joke. But once again, some people thought it was a real magazine and they'd get submissions.

Like for for coming issues, people's portfolios?

People wanted to get work. They wanted to work on Darrow Magazine. The cover is just a photo of me, you know, taken not too far from the Eiffel Tower. It was pretty goofy. It was a big joke, but some people thought it was serious. On the cover it said issue #365. [Seneca laughs]

So Bourbon Thret was the main character of that first comic book, right?

Yep. Yep.

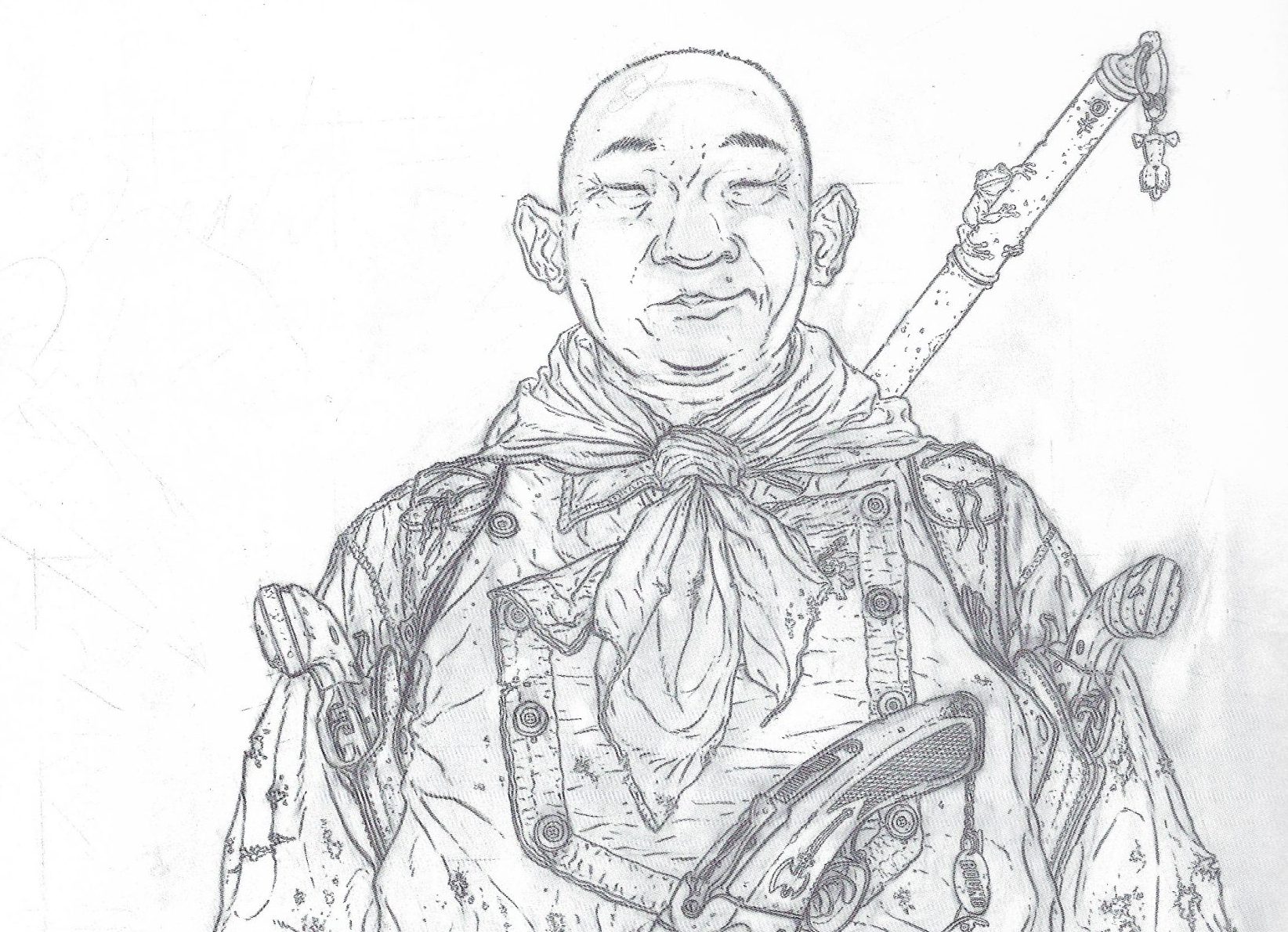

I feel like there's two types of comic book characters - some that are just there to be the magnet that pulls you through all the stuff that the artist is interested in, and some where the artist has a story they want to tell about this guy or this girl or this robot or whatever. I read something somewhere where you said, basically, the Shaolin Cowboy and Bourbon Thret-- that was the Americanized version of the same guy.

Oh, it's the same guy.

Yeah.

I hint at it in the last book.

What is it about that guy? What makes him special? What makes that the guy who you wanna draw all the time?

Like I said, I was a big fan of Japanese movies and kung fu stuff. And I was a really big fan of an actor named Katsu Shintarō who did Zatōichi the blind samurai. I love that character and I thought, I want to do my kind of-- I can't do him as a blind guy, but I liked the fact that he was this kind of a pudgy guy that nobody thinks can do anything. And yet he's, you know, the baddest guy in the room. I thought we got enough comics with, you know, Arnold Schwarzenegger-looking guys. I think most comic book fans kinda look like him anyways. [Seneca laughs] I do. So yeah. I dunno, I can just have him do anything.

But then when I changed [publishers], I thought, well, we gotta give 'em a different title. And [Shaolin Cowboy] somehow came in, 'cause I like westerns and I was watching these kung fu movies. I always like kung fu with the Shaolin priests, and I'd become a big fan of the Jet Li movies that Tsui Hark had directed [e.g., Once Upon a Time in China]. For me, they're like superhero movies anyway. But more interesting.

Definitely. Who was coloring your stuff back in France?

Actually, the first colorist was Nicole Thenen, who was the niece of Hergé.

Oh wow!

And she had colored a lot of the Tintin stuff. She was a very nice lady. She lived in Brussels, and I went there, and she took me to Studios Hergé and I got to see his originals. And there's a gentleman there named Bob de Moor, who did a lot of the ghosting on stuff-- like, if there's an ad campaign and they wanted to use Tintin in it, Bob de Moore is the guy drawing Tintin. He was a cool guy. He was missing a couple fingers 'cause they were blown off during World War II. He was a kid, and a bomb landed in the playground and shrapnel cut his fingers off.

Oh man.

A really cool guy.

So she [Nicole Thenen] did part of it [i.e., Darrow Comics and Stories], and she quit halfway through the second part of the book because it was taking so much time and [the publisher] kept pushing her, and she was like, "well, if you're gonna push me, the hell with it, I don't need it." And she quit. So then it was finished by-- there's a couple pages in there, actually, colored by an artist's wife. His name was Yves Chaland, really fantastic artist who died tragically very young. And his wife [Isabelle Beaumenay-Joannet] colored a lot of his stuff, and she colored a couple pages, and once again it was just too much for her. And then they brought in-- I can't remember these guys' names, but they drove me crazy. 'Cause everything I told them I didn't like, that's what they did.

Mm.

And they always would tell me, "now if you do any interviews"—the Chagnaud brothers, I think it was—"be sure to mention us!" [Seneca laughs] "Always talk about the Chagnauds!" And I'm like, yeah, I'm gonna go-- "So, Mr. Darrow, what are we doing here?" Well, I'm here working with the Chagnaud brothers. [Laughter] The hell with these guys.

Well, you are talking about them.

Yeah, yeah! I don't know whatever happened to them.

The reason I ask about colorists is because there's so much in your work that you're in control of - you know, all the detail, all the little stuff. There's more that's being controlled on the page by your hand than in the average comic, I guess is a kind of weird way to put it. And then you just hand it over to a colorist. Was that a nerve-racking process for you?

It used to be, but I knew that I couldn't do it because it was just so much work. My pencils are really tight, and by the time I've inked it, I feel like I've done it twice. The third time I'll really just crap it out. So, a fresh eye - for me, it's kinda like a present, but it is really scary. I mean, I really liked when I was working with Nicole Thenen from Studios Hergé. And after that, I worked with Peter Doherty, who did colors on the first Shaolin Cowboy, and he was really good. It took a lot of time - I had somebody else whose name I'm gonna not gonna mention, 'cause he was after me to get the job, and I gave it to him, and I said here it is, you know, it's really complicated. "Oh no, I really want to do it!" And he quit, which really pissed me off. [Seneca laughs] He didn't call me to quit! He called the editor and left a message. If you're gonna do it, you gotta get the balls, at least-- it's like breaking up with a girl. You can't-- I guess you do it now by text, but you gotta!

Yeah. You can't leave a message.

You owe 'em that, at least. I had originally asked-- [Darrow chuckles] Mike Mignola always brings this story up. Dave Stewart did an attempt on [Shaolin Cowboy]. And I looked at it, and I was like, well, I don't know. There were a lot of dogs in it. He'd colored the dogs all the same color. And I said, you know, he didn't color the dogs different. [Laughter] So years go by, and these guys quit, and Dave is so good, and I've always liked him. I'll see if he wants to do it. And I asked my editor at the time, and he goes "no, Dave can't do it. He can't do it. He's really busy." Well, can you ask him? "Well, you know, maybe, but he is really busy." So I said the hell with it, and I called up and asked Dave, and he said "yeah, I'd like to." And when I told Mike Mignola, he goes "yeah, but what about the dog color?" I go, ohhh, you still remember that?! And I told Dave that I'd said that.

Dave is the first guy that ever said, "what do you like in terms of color?" And I sent him woodblock print books. I really love that palette from the guys like Hiroshige and Kuniyoshi, and especially a guy named [Tsukioka] Yoshitoshi.

Yeah, yeah!

Ohh, that guy. Phew! When I went to Japan, and I would ask about Yoshitoshi, people didn't know who he was. He's become really popular now, but in the early '80s he wasn't very-- they had an exhibit of woodblock prints at the LA Museum in the '80s, and they had a catalog, and he had a couple pieces in there. I was like, holy cow. 'Cause he could draw, he could really draw, and he'd draw horrible stuff. I think he went crazy. He went mad.

I didn't realize that.

Really horrible stuff. You know, maybe you've seen some of them. The one with the pregnant woman hanging upside down with her belly-- oh man!

So I sent [Dave Stewart] a bunch of this stuff, and I just said that's what I like. And to this day - I don't know how he does it, but he does exactly what I want. I don't tell him anything. He might ask me, "how do you see this?" I go, I don't know. I just got the colors for the fourth issue [of Cruel to Be Kin] and it's just amazing the amount of work he's put in - it's just mind-boggling. I think at most, every once in a while I go, yeah, could you put a little more blood on his socks? That's about it. Before that I'd be really terrified to see this stuff. I'd see things in my head, and then when I'd see [the colored pages] I'd have to kind of let it sit for a while, and then I'd get used to it. But with Dave, it's just like out the gate, it's exactly what I want. I'm always afraid that he's gonna be like, "I can't take this anymore!" [Laughter] "It's too much work!"

What led to having Hard Boiled recolored?

I never liked the color in it. It was outta my hands, because I had done the first issue and this young lady was doing the color, and I told her what I wanted to do. I was back in the States working on something. And by the time I saw it, she had finished the whole first issue. And in those days it was on blue lines.

Yeah.

And doing something over meant doing it completely over. And I was just kinda like - well, there's no blood. She didn't do any of the blood. And she goes, "I'm pregnant. And having to do that blood would make me sick to my stomach. So that's why I made the blood black." That she could handle. I mean, she did a good job. It just wasn't what I wanted. And I felt like I never had any say over it. I didn't have the heart to have her do it over, because it was so much work.

And so, I wanted [the new edition] to be what I wanted. I asked Dave if he'd be willing to do it. For me, that's the color I wanted. I told him what I wanted. People always go to me, "do you realize they recolored Hard Boiled?" Yeah. I wanted it. But a lot of people don't like it. I mean, not a lot of people, but some people complain that--

Yeah, yeah. There was controversy at the time, I remember.

I don't even think I told Frank I was doing it. They're my drawings, I can do what I want! And then I had [Stewart] redo The Big Guy because he colored the monster the way I wanted to. I'd told the same colorist from Hard Boiled I want him to look like the coloration on a wasp, a hornet. And that was too much work for her. I mean, who knows, maybe if she'd had a computer back then she could have handled it better.

Yeah.

But I think she left the field.

So, speaking of these comics - you were in the French comics industry, doing stuff, making work, and then Frank Miller kind of brings you into the American industry, if that's not an inaccurate way of putting it.

Yeah. That's it. I'd moved back to Los Angeles, and I'd met him through Moebius, and I was a big fan. I dunno how we got to talking. I was going over to Moebius' house, and Moebius said, "oh, you know, Frank Miller's coming over, come on over." So I go over there, and I get to Moebius' house, and Moebius' wife is there, and she goes "Jean isn't here." [Laughs] So Frank and Lynn Varley were there. And it was just me and them for like 40 minutes, talking before-- I don't know what Jean was doing. But we get to talking - I guess that's how we got to know each other. When I moved back to LA, I called [Miller], and then we'd just get together. And he asked me one day, "would you ever draw anybody else's story?" I go, well yeah, sure. He goes, "would you do one of mine?" I go, YEAH. [Seneca laughs] He goes "what do you want?" I said, something with lots of action. There were a couple of things we almost did. They were for Marvel, but Frank very nicely said, "you know, you've never done work-for-hire. I don't wanna be the guy that drags you into that."

You were gonna do Daredevil: The Man Without Fear, right?

Yeah, Daredevil. I actually did a few little drawings. John Romita did a way better job than I ever could have. I mean, I also wanted to put him in the costume, because he wasn't in the costume [in that storyline]. Back then, I was like, you know, if I'm gonna do the Marvel thing--

You wanna do the costume.

Yeah. I almost did a Batman/Predator thing. I've always kind of toyed with it. DC was a little nervous that I'd turn Batman into something like Hard Boiled and Mothers United or something would be picketing their offices. [Seneca laughs]

So this is a question that I just-- I was thinking about doing this interview, and I was like, I gotta ask this. Moebius, Frank Miller, and then the Wachowskis. You put those three together, and you've got a pretty strong impact on pop culture for the last 50 years or so. What is it about you? Why are all these people wanting to work with you? Are you just an awesome guy to hang out with?

Well, you'd have to ask them that, I don't know. I never asked any of them to work for them, and maybe that was it. With Moebius, he asked to see what I did. I just figured, aw, people are always bothering him with stuff, and I didn't want to. And he proposed it to me. And then the same with Frank. And with the Wachowskis, I just get a call from Warner Bros., and they had really liked Hard Boiled, and they wanted someone to [work on The Matrix]. A lot of the guys that were available doing that work out in California were the same guys [as other movies], and they wanted me. And the studio was not crazy about it, they really had to convince them. Joel Silver went, "okay, we'll hire this guy."

I don't know. I'm lucky. I mean, if it wasn't for Moebius, I wouldn't have the career that I had. I've always seen myself as a remora, I always end up attached to these larger, more impressive creatures, and I'm just along for the ride, and I benefit from being attached to the great white sharks of comics and films. It wasn't a plan, I'm not a guy that goes, I gotta cultivate a relationship with this guy!

Another example of that is Burlyman Entertainment, the publisher the Wachowskis created to do The Matrix Comics, and yours and Steve Skroce's comics. Was that a collaborative thing that all of you talked about, or did they just say, "hey, we're making a comic book publisher, come make a comic book for us."

That was kind of it, yeah. They really wanted to-- [Laughs] 'Cause I'm a complainer. They hear me complain about my publisher. At the time I didn't feel very appreciated by Dark Horse. And so they said, "well, we'll start our own company." But they were so busy making movies and stuff that it was just-- those comics kind of came and went without people even knowing they're around. It's a real job running a comics company. It's a lot of work.

Yeah, it's not a part-time thing.

And on top of it-- Steve Skroce was a lot faster than I was. They'd go, "oh, we need you to do this," and we'd stop the comics to go do stuff for them. And there'd be these long hiatuses. I mean, Doc Frankenstein, gosh, they finished it almost 10, 12 years after the company-- I dunno if it exists or not. I think it might, just for the foreign sales of Frankenstein. But even then - Doc Frankenstein is a beautiful comic, and Steve did an amazing job. I don't know if people know that it was collected, and it's out there. I don't even know if it's available anymore.

Yeah, yeah. I was looking around-- not very diligently, but I was looking around for those comics when I found out we were gonna do this interview, and there's not any copies hanging out in Oakland.

I think Steve had finished it years and years and years before it was published, and for whatever reason, 'cause they're busy, they'd-- they did a TV show, and they did a couple movies, and it's not like comics is gonna make them a fortune.

Speaking of, do you-- without getting into sensitive topics, does making comics pay the bills for you? Or is it doing stuff for movies, and comics is sort of just the cherry on top?

It did. It's hard for me to say, because I'd always get called away to do something, and I would think of the money. You work on a movie, and they pay a lot of money. I can make in a week what might take me a couple of months in drawing comic. I'm not that fast. I'll work on this movie, and I'll put the money away, and then I can do my comics. That's what I always did. One of the reasons I moved here [to France] was I can live here cheaper. It's fun doing the movie stuff, but it's like-- you disappear, and you no longer exist. It's so funny, 'cause Steve and I would always work together. We'd always be in the same room. And we're always working on these things, going "gosh, I wish I was drawing comics." [Seneca laughs] There's so many guys that wanna draw comics in movies, but they look at the paycheck, it's like, ehhh.

Yeah, you've got to love it.

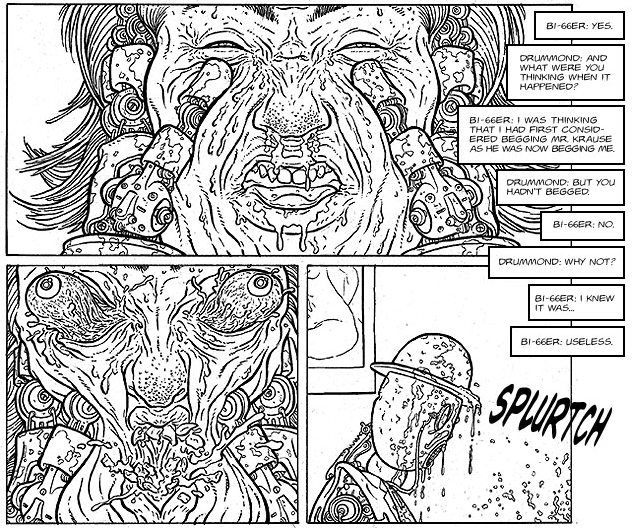

This next comic that's coming out [Cruel to Be Kin]-- while I worked on The Matrix [Resurrections], I worked on a couple other things that kind of pulled me away, but that first real year of COVID, all I did was draw that thing, that next comic. And like an idiot, I drew it all before I started inking. So I had 205 pages I had to ink, and that was hard. Every once in a while I'd stop and I'd have to draw something, and I was like, ahh, that was a nice break. It's two different kinds of muscle groups.

So it's always been comics for you, and that's what you want to do. What is it about the form, or maybe the process, that drives that for you? What do you love about comics?

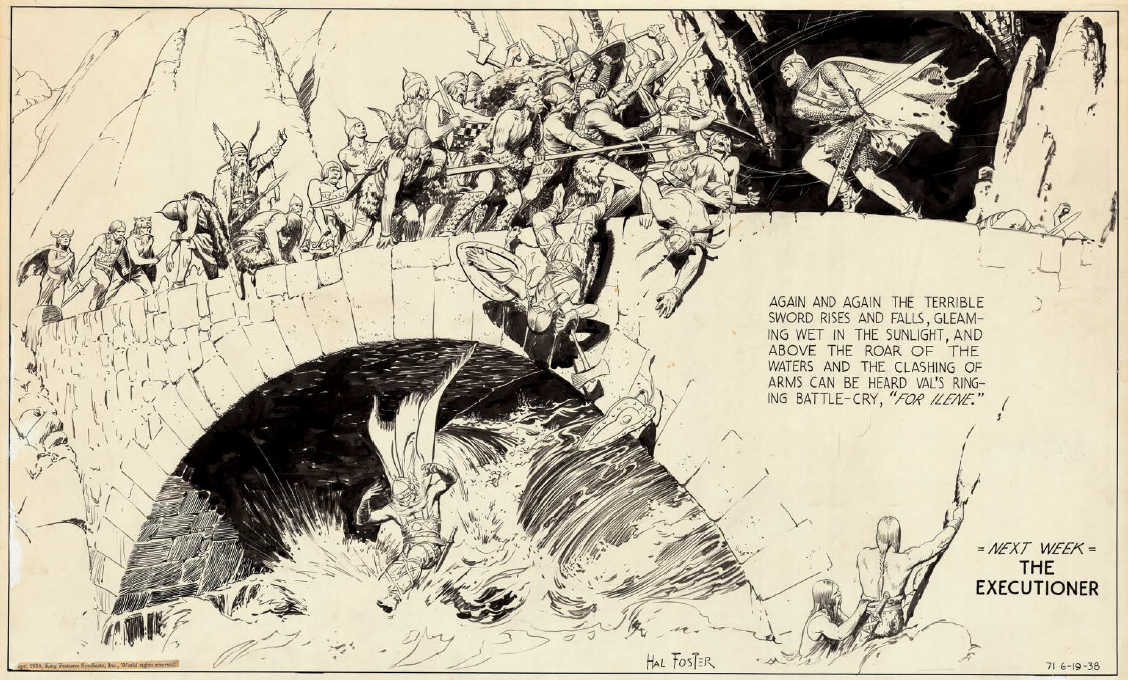

Well, because I can draw whatever I want. I mean, I was so inspired by guys-- you look at Hal Foster, Jack Kirby, and Moebius, and Corben, all those guys I mentioned. Frazetta, and Toth, and the Hernandez brothers, there's so many guys. To be able to actually draw something that tells a story, or just to draw a scene. God, if I could only draw a scene like that Prince Valiant panel where he is on the bridge and he's fighting all those guys, and it looks real. To do something that actually looks real. Kirby's one of those guys that he draws stuff, it's surreal, but it still looks real to me.

Then when you look at guys like Giraud, Moebius, my god, that guy's falling into Suicide Alley and it looks real to me. It's like a movie, and you get to draw your own movie, and that's what appealed to me. You're only limited by your own imagination, and your desire to spend time. Guys say to me, "yeah, I could do what you can do, but I just don't wanna to spend the time." I go, well, then you can't.

That's what it is.

If you're not willing to do it, then you can't do it. I'm not saying you should do it, there's a million ways of drawing comics, and I'm open to all of 'em. I've done interviews where I name people that I like, and I don't look like any of those guys, you know? I still like them. I'm not gonna ape Neal Adams. I couldn't draw like Neal Adams. Jesus, I mean - it's so sad, his passing. My god, what a body of work. He's another one of those guys, you look at his drawings like how the hell did he do this? That one comic where he had Batman with his shirt off-- Batman has hair on his chest, for Christ's sake! [Seneca laughs] I was a kid, I saw that thing and it was kinda dirty to me. "Wow, he's got a hairy chest, I never would've... he's got a hairy chest!"

Even Conan had a shaved chest with Barry Windsor-Smith.

That thing was so testosterone-y, with Ra's al Ghul, and the cowl was just glued down to his-- [Laughter] It never ruffles at all in the wind. And it just seems sexual to me. I don't think Batman ever had sex, but that told me, as a kid: Batman has sex. Bruce Wayne. He is a playboy.

He's putting it down.

Spider-Man, his shirt's off, he's got no hair. Had anybody else ever done a character that had hair on his chest?

I'm trying to think. I mean, it's tough to picture somebody like Kirby doing chest hair.

I always wonder, at DC were they like, "Jesus Christ, he put hair on Batman's chest! Does Batman have chest hair?" They had to somehow dig up Bob Kane and ask Bob Kane. "So, is this canon?" [Seneca laughs] Now chest hair on Batman is canon. Of all the things to remember Neal Adams for...

Talking about the time it takes to make comics the Geof Darrow way, it's impossible not to think about it when you're reading your work. Look at all this work, look at the work that's here. And even though somebody like, I don't know, Jaime Hernandez-- there's a different kind of work in knowing how to simplify. The work on the page that you're obviously putting in is so massive. Do you get off on doing all that tiny little detail, or is it just a slog for you sometimes?

It is. Especially when I'm making it, I go, oh my god, how many cigarette butts-- but that's the way I see the world. I was always kind of taken aback. When I moved to California, I was up in the Sierras, and no matter where I'd go, there'd be garbage. People just treat the world like garbage. I'm not saying everybody has to do this. But you look at comics, it's such a sterile world, and it's pretty messed up, man. And so I feel like I have to do it. I always like the idea that there's all this crazy surreal shit going on, but it's grounded in a real world in terms of perspective and cars and everything there. I try to draw accurately, so that when you've got this goofy thing going on, it's even goofier.

I always felt that if you are drawing a fantasy world-- if there's not a frame of reference for the reader, for me, a little bit of reality there, it's so over-the-top it's not as fantastic. Alex Ross, when he did those Marvels things, he put those characters in realistic situations in a way nobody had ever done. And it was even wilder. I think of Giant Man stepping over the buildings, and all the buildings were drawn correctly, and it was just - wow, yeah! For me, I do it because I think it makes what's going on in the image more crazy.

Do you think of yourself more as a fantasist, or an absurdist?

Probably absurdist, I think.

Your drawings, definitely, they do have that weird kick of being so outré. But the stories that you're doing in Shaolin Cowboy, do you consciously amp up the weirdness? Like, "I gotta make this even stranger!"

Oh, no. Even my drawings always start out to be, I think, probably very boring. Okay, I have a dog pooping in the background. And he's also smoking a cigarette. [Seneca laughs] I do it to amuse myself as well. I also want it to look like I made an effort.

I've got this theory that if you wanna see a cartoonist's style in its pure form, look at drawings of rocks. And you've got probably more rocks in yours than anybody else's. When you're drawing, can you draw anything and be excited by it, and really enjoy it?

Yeah, I do. Quite frankly, I'm shocked when I hear people say "I don't like to draw," and they avoid drawing the thing. I'm not saying I draw everything well. I don't. "I don't like to draw cars," someone would say, and I'd say, you know, I didn't either, and because I didn't, I'm gonna draw it. I don't want to shy away from things, because otherwise-- I won't mention any names, but people, you know, that don't like to do feet... if you drew 'em, you would get over it, and you're not restrained. Then you're not afraid to draw. "Well, I was gonna draw that, but god, I'd have to draw his feet, or I'd have to draw cars, so I'm not gonna do it." So suddenly you've limited yourself in terms of what you can do in a comic book.

The only thing I don't do too much-- I do a little bit of it, but I don't do, like, sex stuff.

Mm-hm.

I mean, I have lots of-- you know, especially this next one. 'Cause I think the big industry is guns, liquor and porn, so there's a lot of strip joints and stuff like that. I was always kind of flattered, because [The Rocketeer creator] Dave Stevens, when I was doing Hard Boiled, there was this girl in it, and he wanted to ink the girl, 'cause he liked the girl. And I just thought, ahhh, I can't. If I give it to him, I won't see it for like a year. [Seneca laughs] He just loved drawing women.

When I was in Japan, I was working on this thing and it was set in a strip club. I remember going to a strip joint, more like a burlesque thing, in this town I grew up in, which was Cedar Rapids, Iowa. And they had a couple of strip joint, liquor places, but it was against the law to show nipples, not to mention anything below the belt. They couldn't show nipples, so the girls would come out and they would dance, and they would wear this see-through gauze. So it's like they're naked anyway, but it got around the law. And these women, they looked like they had some-- it was a rough road.

So I was in Japan, I was drawing these girls in the strip joint, and I drew 'em to look like that. And [Japanese colleagues] were like, "these women are really hard." Yeah, it's not an easy life. And they go, "yes, but are they your fantasy?" No, they're not my fantasy! I'm just trying to draw them that way, 'cause nobody draws them like that in comics. Jaime probably has, but most of the time they always look like they get three squares and they did all their vitamins and all their shots, and they're really happy-go-lucky to be shaking everything in front of an audience. Maybe they are. I used to go to strip joints with Dave Stevens, and I used to like to watch him. Because he'd be studying them, it wasn't sexual, he'd study them to draw them. He'd be saying, "that girl's calves are really amazing." [Laughter] And I'd go, Dave, how's that gal's ankles?

But I would watch the people. I liked watching the people, 'cause you'd have these guys, their tongues are like a Tex Avery cartoon. I remember one time, this sailor starts climbing up on stage, and these guys come outta the woodwork and they yank him off the stage. [Seneca laughs] Just to look at people, just to sit there. You could just see the wheels turning in their heads as they're watching these girls.... I'm not making any judgment on people doing that work. I just can't imagine it's that much fun.

It's a job, you know?

You see people that are just-- you wouldn't want to leave a woman alone with them. What do they call those guys now? There's a term for it, 'cause they can't get a date--

Incels.

Yeah, incels in these places, you know?

You can witness some humanity for sure.

Oh yeah. That's why I liked going with Dave... I'd inadvertently be told by the dancer to pay attention.

I always had this theory that if they were gonna do a movie based on one of your comics, like adapt it-- I think Hard Boiled was the first one I thought this about, but Shaolin Cowboy could be the same thing. I always kind of thought that if they were gonna do a movie version, the whole thing would have to be in slow motion. [Darrow laughs] Or like they crank the camera too slow or something. Because your comics read like that. You're taking a lot of time and a lot of space and pages, and-- especially in the new one, there's a lot of panels on those pages. What drives you? There's a part in the new one where the dad monitor lizard is talking to the son and saying 'I was 60 seconds old, and by the time this whole 20-page sequence was over, I was 64 seconds old.' What is it about slicing apart time, taking 20 pages to depict four seconds that appeals to you?

I don't know! I thought it was funny. At the time that wasn't my intent. I don't write out full scripts. That's probably evident looking at what I do. I just know what's gonna happen. I just wanted to give the impression-- as [the series] goes on, there there's even more of that. I have a hard time getting people out of a room, for instance. Well, maybe they'll get a sandwich, and then they'll put on their coat, and - just cut to them going out the door, for god's sake. But I think it's funny. I inadvertently-- and this is odd. I'd seen this Robert Altman movie called Nashville.

Yeah, I actually just watched that a couple months ago.

And I was taken with it, because there is no story. It's just like a piece of time. And I always thought Shaolin Cowboy, like the one with all the zombies [Shemp Buffet]--

That's the one that I think shows your tendency to the--

That's like 20 minutes, I think, 25 minutes [of time passing in-story]. And then when you get to the one after that [Who'll Stop the Reign?], a night passes, but if it wasn't for that night, it's still only another 20 minutes, 'cause once he gets into town, things start to happen. I've always sort of seen [the series] as kind of a promenade, a ballad, him walking from Point A to Point Z, and someday he'll reach Point Z, and he'll be dead. If that makes any sense.

It's interesting, because that's that kind of-- I don't know, I don't even wanna say storytelling. That kind of presentation, I guess, is really something you can only do in comics.

Yeah.

Is it just wanting to show everything? Like, I gotta show this, I gotta show that, I gotta show the move he makes here. Or are you conscious of doing a formalistic thing and exploiting the possibilities of the medium?

Nah, I just think, can I do this drawing? Can I do the drawing of him doing this? That whole chainsaw thing was just-- the inspiration was Evil Dead. Ash had a chainsaw, and I can't put a chainsaw in [the Cowboy's] arm, so in the first book [Start Trek]-- I dunno if you remember it, but he's in the belly of this beast that's full of sharks, and eventually zombies, but he's on the back of a bloated dead cow and he needs an oar, so he makes that so it's almost like a kayak, but it's a chainsaw. Then he can fight just like Ash did in Evil Dead. [Laughs] And I'd seen these kung fu movies, I'd see Jet Li spinning the staff around and - yeah, but what if there were chainsaws? I don't think anybody's ever done that.

So, if I want to draw something, I want to see if I can actually draw it, like a car smash or a car pile-up. As you continue to, hopefully, progress in your drawing, you realize you can draw something that you couldn't draw before. Maybe I'm just fooling myself. But you know, I go back to Moebius - when I got his first book, it was a Lieutenant Blueberry book, and there's a panel in it that I could not fathom anybody ever being able to draw. And I go: god, if I could someday do a drawing that I didn't think I could ever do...

So, are you conscious of testing yourself and becoming a better artist on the page?

Yeah, but I don't see myself as a technique guy. I always feel like such a moron, you listen to Mike Mignola talk about patterns of this and that, new shapes and this and that - I don't think that way. Or Dave Stevens would going on and on about using a brush, the brush is the only way to do comics, and I'd go, well, that's not the only way. I mean, the way he wielded a brush, yeah. Even if I could use a brush, the kind of stuff I do, you can't. Maybe you can, Neal Adams probably could - but inking a car with a brush, I don't know.

That's tough.

And that's the kind of stuff I've always been interested in... I've never been, oh, what if I get a toothbrush and spatter [the ink]? I'll draw the things out first. I'm interested in drawing it. I'm always surprised that I could-- wow, I was actually able to draw a tennis shoe! [Seneca laughs] I find that magic. Wow, I could draw a tennis shoe. Or a car, or an airplane. Horses are always the hardest thing to draw.

Yeah! For me, oh man, that's--

It's the musculature of the chest. It's just so, so weird. The way the hooves works, sometimes you'll draw them and they'll be in positions they can't be, because their front legs are like our arms. They can't bend back, or they can't twist things around.

Yeah. The hooves being just like a toenail, and the rest is up in the air.

That whole mass, the muscle mass and the front of a horse is just crazy, man. There's these really big shapes that you can look for, but--

Hal Foster, he was the master of horses.

Giraud too could do horses. Jack did a pretty good job, Jack Kirby. I don't see a lot of people doing animals, you know?

It's tough. Animals are hard.

They are, but if you just look at 'em... I have this old book I got at Hanna-Barbera, Ken Hultgren [The Art of Animal Drawing]. It's great, 'cause it breaks 'em down. I guess he was a Disney animator. Most of the guys in animation had this book, because it was really helpful.

So what do you like to draw? If you could only draw what you love to draw for the rest of your life, what would that look like? Would it look like Shaolin Cowboy?

Yeah, that's pretty much it. Every once in a while I think about-- I'm real childish, and I'll go, I shouldn't watch a Marvel movie 'cause I'll want do a superhero thing, and there are too many of those and people way better at it than I am...

If you could describe the kind of comic you want, what would you say about what you want to make?

A comic book that's action-packed! [Seneca laughs] I remember when I was with the Wachowskis-- when they did their press junket for The Matrix, they'd come to Paris and I was living there. And so they invited me over to be with them while they did their press stuff. And it's funny, if you see any of these reports, the interviews on TV, you see both of them sitting there, and sitting between them is me. The reporters are like, "who is this guy?" And nobody ever asked me a question. I'm just sitting there. But they asked [the Wachowskis] to describe The Matrix, and they said, "it's kung fu versus the robots." And I go, yeah, there you go! [Laughs] Their answers got much more philosophical afterwards, but I still remember that. Yeah, kung fu versus the robots.

Simpler is better sometimes.

It was a fun movie. I always like movies where if you want to find more than the surface matter, you can, but if you don't, you just wanna watch it for the action, or the visceral parts of it, you can. I think of The Searchers, or Yojimbo, where it's great action things, but if you think about what's going on-- there's a lot going on in there, but it's not in your face.

Right.

I always think if you can do that, you really accomplished something, as opposed to preaching to people. Walter Hill [says] you show who people are by their actions, as opposed to them stopping, going [tough guy voice:] "When I was two, I saw a jaywalker. That jaywalker caused a car to have an accident. So I hate jaywalkers! I'll always go after jaywalkers!" Something like that.

There's a lot of that in comic books, you see it all over the place. but yeah, you're right.

As I look at it, Mike Mignola, I think he's a great writer, but he just lets it be. As opposed to, like, "that creature from a stygian hell is most indecisive, and he had to be put down." Mike would write it: "Yeah. That's it for him!" [Laughter] You know that this is a bad thing, and he got rid of it! You don't have to wax on about why he did it, 'cause it's obvious why he did it. Seamless writing. It seems effortless, though it's not.

Yeah. Less is more.

And Jaime's the same way. Jaime and Gilbert. Dan Clowes.

Do you think your comics have had an influence that you can see? Do you do you feel like you see stuff, and you're like, yeah, that guy's out there doing that 'cause of what I did.

Yeah, there's a few guys. There's one guy that did something and I didn't like it, 'cause I don't like it when people copy your drawings. I've seen it in movies a little bit.... I don't think people would wanna do what I do, 'cause it's just too time-consuming and probably boring for most people to sit there and try to figure out, you know, a tin can in perspective or something. Like, it's not that important. Those little things are important to me, and they probably shouldn't be, so it'd be a waste of most people's time. So I think people are well-advised not to try to be influenced by me. Maybe my work ethic.

It's impressive that you're still cranking out incredibly elaborate, detailed comics after all these years.

Yeah, but I haven't done that many.

What keeps you at it, though?

'Cause I don't know what I'd do. If I couldn't draw, I'd probably put a bullet in my head. If I'm not drawing, I'm okay for a couple hours, and then I get depressed. I'm really bad at taking vacations. I drive my wife crazy. When my daughter was younger, I'd go with them, and I'd always bring work with me, 'cause after about a day, I just-- I'm horrible. Except in Tokyo. Tokyo, I can go to, 'cause I just like walking around there.

A lot going on.

You know, that's the only place in the world I ever drink. 'Cause I don't drink much, even there I don't drink much, but I like going to, you know-- it's like being in Blade Runner, Tokyo to me. There's so much stuff that I like there.