“Sūpā onanī hissatsu-waza: Ikegami Ryōichi Supaidāman”

From Seishun manga retsuden (Legend of Manga’s Youth; Magazine House, 1997), pgs 35-41. Later republished as Ano koro manga wa shishunki datta (Back Then Was When Manga Was Coming of Age; Chikuma Bunko, 2000)

* * *

The following essay is from Natsume’s twice-published collection of “manga columns” from the late 1990s. It originally appeared in print in January 1994 in the newly-relaunched men's magazine Marco Polo (Maruko Pōro); this essay is also the inaugural installment of Natsume’s Seishun (“Youth”) series, which would run for one year in Marco Polo before Natsume transitioned the column over to the literary magazine Oh! Pigeon! (Hato yo!), where it ran for the next two years. Readers of Natsume’s essay on Miyaya Kazuhiko, which TCJ featured last month in its effort to provide a fitting tribute to the recently passed gekiga auteur, will notice a similar tone and approach in this assessment of fellow gekiga artist Ikegami Ryōichi and Supaidāman, his marvelous work adapting Marvel's wall-crawler beginning in 1970.

In his Seishun essays, Natsume (born 1950) willfully conflates his own coming-of-age trials and tribulations with those of the manga and gekiga characters he read during that phase of his life in the late 1960s and 1970s, looking to record, as he later assessed, “those raw (or vibrant) interactions between me and manga” from that time. (See the Afterword/Atogaki to the book collection’s second edition in 2000.) Natsume nostalgically reconnects his own early days as a “manga young man” (manga seinen) with the manga about, created by, and marketed to that emerging demographic. These essays are gross conflations, while the conflations therein are also sometimes gross. Men are full of contradictions. These “manga seinen” were, in fact, drawn to gekiga (dramatic pictures), so the terms “seinen manga” and “gekiga” could be and often were synonymous. That both the young men and the genre were in their “youth” (seishun) is the point of these essays, in which Natsume explores the messy, mistake-ridden, but fresh and exciting discoveries that these baby boomer males and their favorite comics were making. One might even go so far to say that “youth”, “sexuality”, and “gekiga” were synonymous with each other - at least by the 1970s, as Supaidāman made the manga scene. It is no wonder that Natsume, in this essay, will playfully seat masturbation, Ikegami, and Spider-Man all at the same table.

We thank Natsume-sensei for allowing us to translate and publish at TCJ again. (Although the 72-year old author joked with us that "TCJ" might be getting "TMI" with all these essays about his budding sexuality…) Finally, we recommend readers interested in Ikegami’s Spider-Man manga to check out another recent TCJ essay penned by manga historian Ono Kōsei.

-Jon Holt & Teppei Fukuda

* * *

5478 times. Ōtsuki Kenji has a collection of masterwork short stories, entitled Gumi・Chokorēto・Pain (Gumi-hen) (Gummy・Chocolate・Pineapple (Book: Gummy); Kadokawa Shoten, 1993) and it suddenly starts with that number: 5478. That is the number of times the 17-year old protagonist, Ōhashi Kenzō, has been doing masturbation since his last year as an elementary school student. “I am totally unlike those crass, boring people around me,” he thinks while repeating his daily habit of masturbation. But, because of his personality, he ends up in the story never being able to speak to any girl.

“Gosh,” he thinks, “maybe if I keep it up like this, my sex drive might just go away.”

“Well, it might be even better for me to just fade away into the darkness.”

And so on, and so on, he continues to gloomily think, living life completely at a loss what to do. For myself at 43 years old [at the time Natsume wrote this], I can laugh at this kind of thing, but I often ended up agreeing about the same topics. Maybe we belonged to different generations, but similar guys will do similar things, oh yeah, and we worry about the same old stuff.

It’s probably a bit problematic to say this in a super-confident manner, so I will try to say it with a bit of hesitation, but I too did the exact same thing as him. As a person who knew not what to do with a swelling self-consciousness and a bulging willy, concerned as I was with my erythrophobia, and, as a person who was a constant worrier, for a while I would masturbate once a day. There was this guy I was friends with in middle school who asserted a dubious theory: “As long as you do it not more than three times a week, it won’t affect your mental development.” Then all my pals would say to each with a straight face, “Oh, in that case, I guess we’re okay then,” but they were all just like me and we all secretly despaired with thoughts like, “Shit! I might be frying my brain!”

There was even one guy who had come up with a completely illogical “special technique” (hissatsu-waza), telling us, “It’s okay guys, ‘cause when I come, I hold it super-tight so nothing can get out.” We all looked at him telling us that with suspicion, but of course I went home later that day and tried his method just to test it out. It might be that on this point, all boys and young men have this in common as they try to get through this phase in their lives.

However, he had no need to worry. Because it’s actually more normal if one does do that stuff.

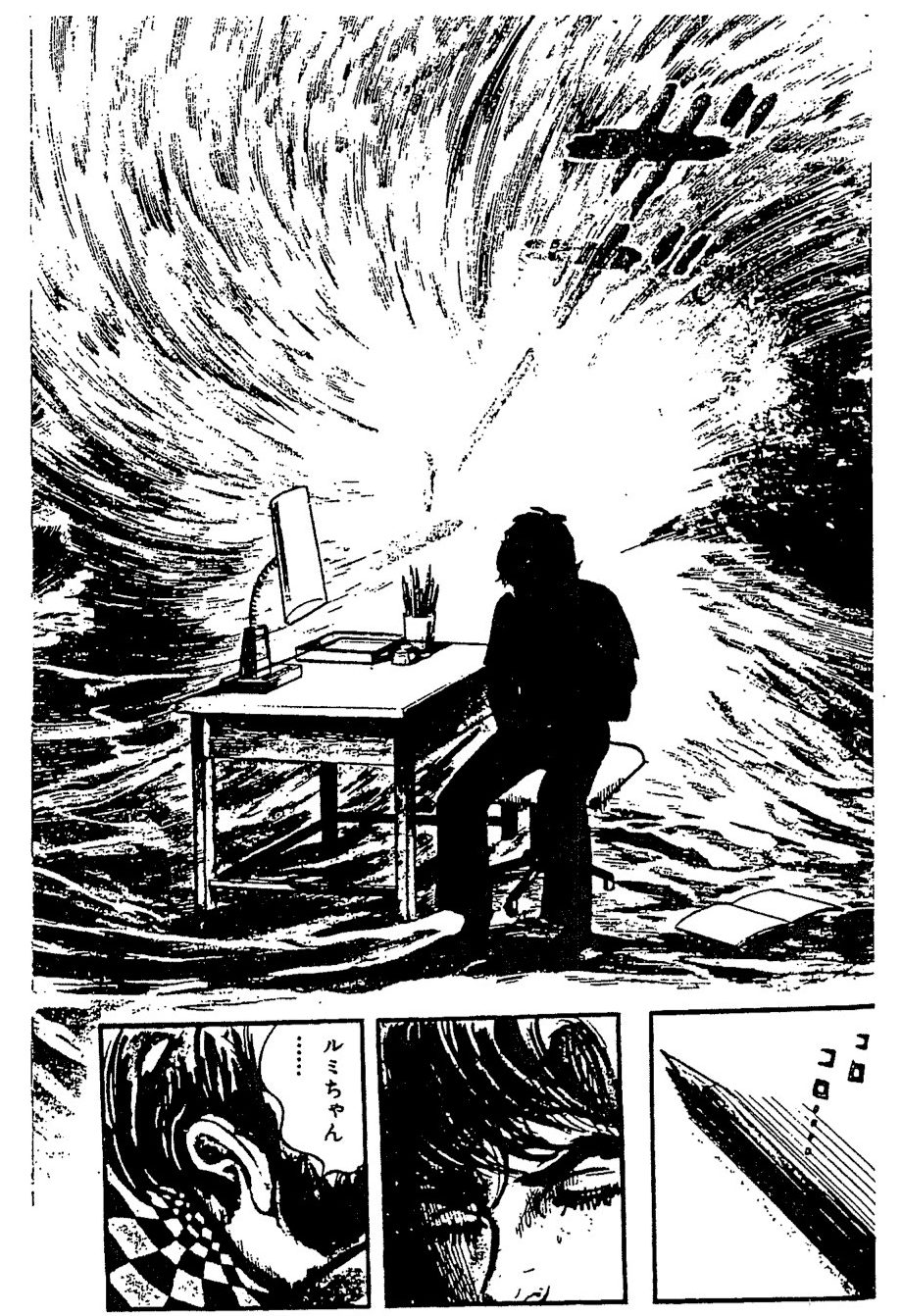

C’mon, even superheroes have times when they masturbate. At the start of the 1970s, in the Supaidāman (1970[-1971]) serialization (in Monthly Shōnen Magazine), even the protagonist Komori Yū—even Yū-kun—can get really worked up while thinking about his darling Rumi-chan. In his fantasy, he ends up chasing after the swimsuit-clad Rumi-chan and pulling off her bikini top. “Why do I have this same dream night after night?” he asks himself and cradles his head [in shame]. If you think about it, it actually was pretty rare in that time to have a scene in a manga where the hero masturbates.

Even so, it is a pretty flashy masturbation scene (Figure 1). It is a surf-scene masturbation, with waves and all. Well, not exactly, because there is no way that it could be happening on the beach; instead, these images are metaphorical. Because immediately after the scene, we see [a panel with] a pencil rolling over slightly and making these cute little rolling sounds. It makes me cry at how adorable it all is. While the raging billows are a combined image of his sexual desire and ejaculation, they also suggest the protagonist’s psychology, wet with shame, through those foaming waves. So, when we get to the cowardly-looking rolling pencil, it quite enough conveys the kind of emptiness any guy feels after doing that kind of thing. (Well, most likely.)

This kind of artistic expression was definitely something that was in line with the innovations brought by the 1960s seinen (young male) gekiga movement. It is an expression with the power to depict the internal feelings (naimen) of frustration experienced by boys and young men. Ikegami Ryōichi, the artist who drew Supaidāman, had a style of… well, what’s the best way to describe it? Ikegami had a “dug-into-the-dark-part-of-humanity” style. How about that? Anyway, he took off with his stories in Monthly GARO, working in that kind of style of gekiga. Later he would become an artist who developed an aesthetic in his line that showed an exquisitely gorgeous and dry form. This took him some time as he moved on to those later works, like Aiueo Boy (Aiueo bōi) and Team of Men (Otokogumi), but when he was doing Supaidāman, there was still something kind of mushy about his linework.

He did not only extend his metaphors to things like masturbation. For example, at one point in the story there is a scene where a pretty young woman suddenly appears out of nowhere in front of Spider-Man (Figure 2). There is a panel on the right-hand side with a landscape scene from which he transitions to the picture of the girl. Ikegami creates a kind of gap with her, where we go from a distance shot to something nearby, and the effect is to suddenly pull in the reader’s line of sight to the girl. Behind her head, there is a panel that encloses a cherry blossom branch, and this gives the girl a greater impression because Ikegami entirely frees the girl by clearing off her panel border.

It doesn’t mean that the girl’s brain is like some daft partygoer’s at a flower-viewing (hana-mi) picnic. Instead, Ikegami hints at the girl being like a flower, so we know there is a nuance of excitement here for the protagonist [Komori Yū], and it gives us new insight into his psychology, so perhaps he is thinking, “Ah! So cute!” Using a metaphor like this is a classic move in Japanese manga, where the artist will use everyday scenes such as this as a secret ingredient to spice up the manga.

Before this period, in the 1960s, one of the goals of the vanguard manga artists was to try to find a way to draw the most mundane psychological scenes and make them interesting to look at. In the narrative descriptive parts of the drama, they will put in a landscape or play with the panels, but put them on top of them so as to not let the reader get bored. They would use things like close-ups with characters to get more readers to transfer their feelings to the character. This kind of technique, even now, still maintains its interesting qualities in Japanese comics (well, at least for Japanese readers).

The Spider-Man character, as I am sure my readers already know, was a hero produced in America by Marvel Comics. The Japanese domestic acquisition of the license to the character came about through Ono Kōsei and Uchida Masaru, the famous editor who created the 1960s blockbuster Shōnen Magazine (Shōnen magajin). A bit into its serialization, Hirai Kazumasa was brought on to write the scripts. At that time, I, as a reader back then, felt the series suddenly got way more interesting after Hirai’s scripts were used.

Even the American original was a forerunner of Marvel’s later anti-hero characters, and although he did his share of worrying and whatnot, to readers like myself who were used to Tezuka Osamu-style manga, we would see him [in the American version] and think, “Are you really doing all this right now?” Instead, the way the [Japanese] character frets in the Hirai scripts is something more sentimental, more filled with something like a grudge. Maybe Hirai’s stories were better suited for Japanese audiences. I guess they came at the right time, because it was the period in Japan in which excessive distress was all the rage.

Every girl that the protagonist loves will end up bearing some tragic fate, which is why they all run away from Komori, which in turn makes things all the more tragic (come to think of it, that seems like something out of a kayokyoku [Japanese pop song]). Anyway, there is usually a pattern where all of this makes Komori/Spider-Man explode with anger in each tragic scene. I was 20 years old at the time, and so this pattern of tragedy unexpectedly resonated with me. Maybe it was because I was a person who actually liked tragedies more than I thought I did. It was also just that tragedies were popular with a lot of people at this time.

I say that, but the person who first introduced such a sense of tragedy into manga—actually into sequential-panel comics (perhaps the first in the world)—was the famous Tezuka Osamu. The techniques that Tezuka used to develop his character-based dramas made possible [in manga] a kind of prosaic form of psychological description. He established a sense of outlandish drama by bringing out his characters’ worries and their frustrations. Gekiga [artists] in the 1960s were trailblazers for how they in turn further visually expressed the metaphorical mental states and the emotional pain of their characters. They ended up taking this so far that they would have their work entirely consisting of interior struggles of their young male characters.

It is only because we have these initial few layers of substratum that we can get even Spider-Man masturbating. I would think that this kind of thing just would not have been possible in American comics. Japanese manga has long been drawn in a way to get its readers to transfer their feelings to the interiority (naimen) of the manga characters. This is what makes Japanese comics so different from those of America and Europe, of Taiwan and Hong Kong. (And yet I have a feeling that Korean manhwa are closer to Japanese manga on this point.)

Ikegami’s art style has had a lot of influence on kung-fu manga (bukyōmono, “heroic tales”) produced in Hong Kong today,1 so much so that some of their heads look just like Ikegami’s! But when we [Japanese] read these Hong Kong comics, they do not really resonate with us. They are all just battle exchanges with one super-technique (hissatsu-waza) after another—they don’t have any individuality because there’s absolutely no normal, no human drama to them. Because they are like that, they seem only like film trailers, and in the end there’s no room for the reader to invest any feeling in the characters. Okay, the art in them is pretty good, but they are not that interesting as comics.

* * *

(click and drag left to see the images)

However, going back to Ikegami’s cherry-head girl, I actually had a strong personal feeling with her. The girl reminds me of someone I knew and liked when I was 19 years old. I remember back then being so surprised at her, that I nearly choked as I read this story. “Why do I have to see this girl even in my manga?” She only seemed like that to my eyes, but I do not know whether she really looked like Ikegami’s girl.

The girl in Ikegami's story is a tragic figure who must sell her body as a prostitute in order to save her younger brother. The person that I knew was a good girl from a good family that was pretty hard to ever get close to. Hers was a very rich family. She has a superior sense of fashionable attire. But she was also so brazen that you couldn’t stand to be around her: she could be shy; she could be selfish; but she had this sparkly thing about her. Eventually I was able to win a date with her, but because this girl had both brains and hobby interests—she could handle movies, literature, and music—I could not keep up with her and spar with her on any level of conversation. I was a guy who had a poor education and no money. I was that guy who had just recently been a pathetic masturbating kid. What little self respect I had was rumpled up like a Kleenex tissue. In the end, with the way things went, I never did confess my love to her. I did eventually find a girlfriend, yet it was not to be her.

In the early phase of Supaidāman’s serialization, young Komori Yū had the face of an innocent boy-hero (Figure 3), but in the latter half of the series he begins to have the forlorn face of a young man (seinen), so common in Ikegami Ryōichi’s later works (Figure 4).

The two images seem like a perfect epitome of the seinen evolution of manga into gekiga from the 1960s to the 1970s. As a reader, I projected into Komori’s face my own internal mental changes that I was feeling as I grew from my teen years into my 20s. It was just my interiority though. I never did have a handsome face like Komori’s.

* * *

- [Editor's Note] For example, the wildly popular HK cartoonist Ma Wing-shing is an avowed admirer of Ikegami. English readers will recall Ma's series The Blood Sword (aka: Chinese Hero) in translation from the infamous Jademan Comics, as well as later translated work such as Storm Riders from ComicsOne.