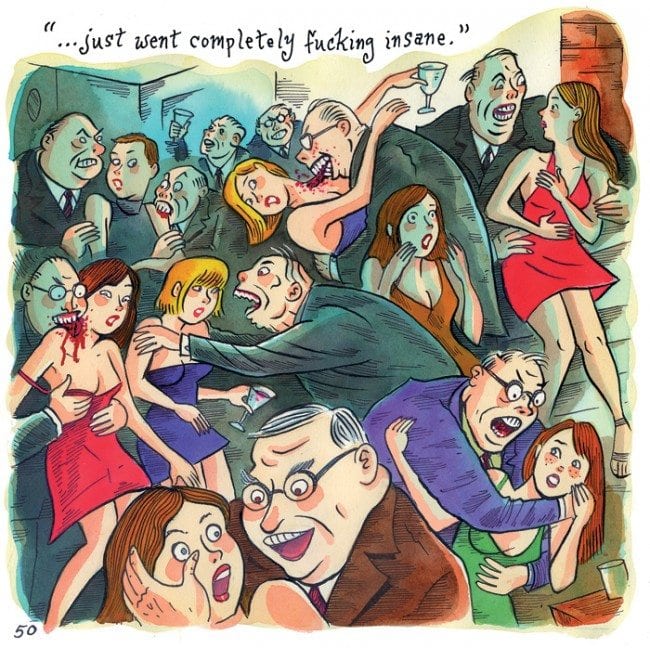

For more than thirty years, the illustrator, cartoonist, and painter Richard Sala has been exploring a broad but remarkably consistent set of artistic obsessions: labyrinthine conspiracies, psychopathic homicide, weird pseudo-science, masked criminals (and crime-fighters), occult rituals, preternaturally self-possessed girl detectives, monstrous perversions, mad ventriloquists, evil hypnotists, and similar outlandish subjects. He usually approaches this dark material with a lightness of touch and subtle humor that recalls such obvious cartoonist predecessors as Gahan Wilson, Edward Gorey, and Charles Addams, and a willingness to "go there" which echoes the goriest EC Comics and underground artists as well as, more directly, the ultraviolent gangsterland fantasias of Chester Gould. An artist who wears his influences on his sleeve, Sala draws visible inspiration not only from those comics-world figures but also from a wide range of literature, cinema, and fine art (Borges, Poe, Bava, Lang, Feuillade, Goya, to name a few). But Sala is much more than just a cultural remix artist, and his sardonic and thoughtful approach to storytelling is unmistakably his alone. Sala's best stories go beyond mere grotesque fun, creating sometimes a sense of genuine dread, and others an amused appreciation of the true absurdity of life and human civilization.

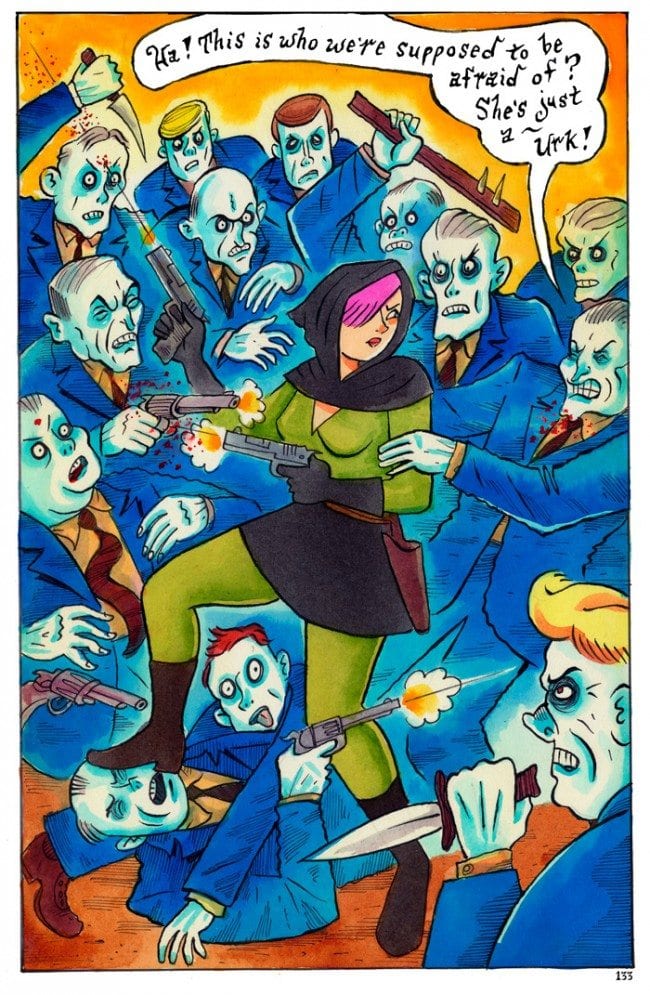

Late last year, Sala released a new collection, Violenzia and Other Deadly Amusements, gathering stories about the title heroine (a seemingly invulnerable force of vengeance), as well as "Forgotten", something of an illustrated prose-poem meditating on colonialism and humanity's lack of moral progress, and "Malevolent Reveries", a gallery of macabre illustrations. Most recently, he has just launched a new online serial, The Bloody Cardinal, which promises to follow in the tradition of his early classics, The Chuckling Whatsit and Mad Night.

This interview was conducted by email in late March.

Most of what I know about your personal life comes from your interview with The Comics Journal in 1998. What is your situation now? Do you still make your living primarily as an illustrator, or has comics become lucrative enough to be your main source of income?

Very little has changed, I guess, on the surface. The life of any freelancer, with certain exceptions, is not going to be a bed of roses. You have to make sacrifices, if you want to survive. There were several trips to the edge of the abyss and I expect more in the future. That was the choice I made. I wanted to be a working artist and have a chance to carve out a small career - with all the ups and downs that entails. A drawing table by a window and doing work that I want to do. And I'm still at the same drawing table I was back then. Still working away.

That TCJ interview, by the way, I kind of wish didn't exist. It captured me at a time in my life when there was a lot of frustration. I was kind of a nervous wreck and for some reason I got defensive and it shows up in my attitude. I was not at my best at all. It's the only interview I've given that I look back on and regret.

It's surprising that you say that, because I really love that interview, and thought you came off really well in it! I don't think I had really understood how ambitious you were until I read it. At that point, I'd only seen a few of the installments of The Chuckling Whatsit in Zero Zero, read out of order months apart, and didn't really get them. I assumed they were some sort of Edward Gorey ripoff. After reading the interview, I went back and read the whole thing at once, and fell in love with your work. (I was also prompted to look into a lot of great books and authors you mentioned; it was a terrific introduction to a lot of fascinating art and literature.)

Well, thanks. That's nice of you to say. The whole experience is probably exaggerated in my memory. I just remember having to explain myself more than I'm comfortable doing, and consequently going off on rants about things that actually weren't important to me at all. Just feeling defensive. I love sharing information about things I enjoy or that inspire me, so I'm glad you liked those parts. The funny thing about taste in popular culture is that it's so subjective and personal. Every generation loves what they loved as a kid and by the time they're adults they can write thoughtful and passionate defenses of even the lamest Saturday morning cartoon. There will always be people who tell you that something you like "sucks" or whatever, but it doesn't matter what anyone else thinks if something is meaningful to you on a personal level.

When I interviewed your friend Dan Clowes last year about The Complete Eightball, he spoke about how much of his early work, no matter how outwardly outlandish and non-realistic, often had many autobiographical details hidden in it that he could only recognize in retrospect. How autobiographical is your work? Not just in terms of reflecting your personal concerns and psyche, but your actual circumstances?

I would say there is almost zero relationship between any actual details of my life and the details in my comics. Psychologically - that's another story. Psychologically, something like Delphine is a self-portrait. It's a depiction of how it felt to be me at a particular time in my life. There may be some small real life details throughout my books simply because I lived in a certain town or worked a certain job, but nothing close to autobiography - which I wish I could do, but can't. I just don't have the right temperament. Everything I create is a plummet into my subconscious - it's all comes out of childhood repression and sublimation and displacement and wrestling with demons. I can't imagine writing about myself goodnaturedly fumbling through life or whatever. When I try to, I get flooded with too many choices or points of view to explore. It's a serious limitation for me. I admire people who do autobio and diary comics because I love reading those. It's one of my favorite kinds of comics to read, especially when it's done with self-deprecating humor. Or when it's a comics journalist exploring a subject with personal insights. I could read those all day.

Your work is remarkably consistent, not only in terms of quality, but in terms of subject matter. Obviously there are always variations, but you generally stay in the same gothic/fantastical horror/mystery/adventure zone: I know you have answered this many times before, but what is the attraction of this kind of story to you? Do you ever get tired of the macabre? Have you ever been tempted to try your hand at anything markedly different (a romantic comedy, say, or courtroom drama, or historical piece)?

At some point you have to figure out your strengths and your limitations. Alfred Hitchcock did a romantic comedy early in his career - just one. I don't think his heart was in it. His strengths and interests were elsewhere. Most really good artists have a limited number of obsessions that they explore over and over again, each time in a new way. They are able to keep it fresh and it's recognized as part of their style. Have I been tempted to try doing a western or a romance or a war story? Absolutely, and if I can figure out a way to do it while still being myself maybe I will. In the meantime, I tell people that Delphine was my romance comic.

On the other hand, as an illustrator, I get assigned to draw all kinds of things I wouldn't otherwise. That's fun and challenging. But when I sit down to write a new story, the ghosts and phantoms and maniac killers always come out.

In recent years, your stories seem to have grown more and more overtly political and angry— "Super-Enigmatix", The Hidden, "Forgotten", etc. Has this been a conscious decision on your part? Some might argue that such themes have been been sub-textually present in your work all along, but they certainly seem more pointed now.

The first book I did that was an angry reaction to current events (during the Bush years) was The Grave Robber's Daughter. It's not overt, but that's what was on my mind when I did it. It's about cycles of violence that never end. I drew that book really fast. Normally I would have redrawn some of those pages several more times to get them to look a bit nicer. Some of the drawing is pretty raw and sloppy. It probably could have been a great book if I had worked on it for another six months, but I just wanted to get it out of my system.

The Super-Enigmatix story [collected in In a Glass Grotesquely] is absolutely inspired by living in the world today - just the craziness of it all. Oddly enough though, what inspired me were older, pulpy stories about disasters and destruction, many from the 1930s. But my main influence for "Super-Enigmatix" was something that made a huge impression on me as a kid - the original Mars Attacks card set (not the movie version which is just a dumb joke, and I don't know anything about later comic book versions or whatever) which some of the older kids had and would pass around or trade with you

In those original cards, Washington, Paris, London, etc - as well as innocent individuals (a doctor driving in his car, a boy's beloved dog) were obliterated gleefully by these evil things which were like the ids of the country running amuck, a reaction to the stultifying 1950s. It was scary and thrilling and shocking. The tongue-in-cheek factor was there (Martians drinking cocktails while watching the destruction), but it was what used to be called "black comedy", like Dr. Strangelove. Just pitch-black, angry humor, and, I think, a good catharsis for kids who were dealing with the free-floating anxiety of the atomic bomb dropping on us any minute.

An older comics critic wrote to me about "Super-Enigmatix" and said he was disturbed by what, to him, was a sadistic and nihilistic book. So I get that it's not for everyone. It's not everyone's cup of tea. But it came out of my own anxiety about the state of the world today - so I just threw myself into the lunacy. The irony is that at its core the story is about a relationship between two individuals who met when they were kids, one of them realizing at the very end that maybe all the horrors she has witnessed might have been prevented by a little kindness. You're not hit over the head with it, because that can seem more than a little trite, no matter how true it might be - but it's there.

But yeah, angry rants are fun to write, whether I agree with them 100% or not. I'm aware that they can stop the story cold, though. But even knowing that, I just embraced it as maybe an interesting idiosyncratic quirk. "Oh here comes five pages of angry text." It's something you can do if you're with a small publisher and have a tolerant editor.

But there's nothing like that in my new webcomic. It's back to mystery. Let the world take care of its problems. It's hopeless trying to change people's minds about anything anymore. On a positive note, it's kind of exciting to be living at a time when civilization is cracking all around us. It's a good time to make art, in the face of all the daily horrors and sorrows. The art will survive long after all of today's politicians are gone.

Enigmatix".

Perhaps coincidentally, many of your stories also seem to have grown more seriously frightening and less campy in recent years. Humor is still a frequent presence, but Delphine and The Hidden seem (to me) to be striving for genuine sustained horror in a way that most of your earlier works didn't. Have you made a conscious shift in that direction?

I don't think so, not intentionally. But changes like that may happen as one grows older or lives life, I suppose.

What has always appealed to me over everything else, beyond horror or comedy or whatever, is a sense of the absurd. I think I got that from reading Kafka in high school and feeling a shock of recognition. I felt a kinship with absurd humor and black humor. Having an appreciation of the absurd - along with my childhood love of monsters - helped me survive in what was a dysfunctional (that is, crazy) household. I was drawn to the surreal and the expressionistic and the unreal, which is where I felt at home.

Maybe I'm making it sound like my comics are all about exorcising demons, but that's just behind the scenes stuff. When I sit down to write now, the shades of darkness may vary, but there is always a sense that what I'm making is in some way, a comedy. I want to give my readers what the work I loved as a kid gave to me. It's supposed to be entertaining first and foremost.

I recently re-watched Alphaville, which I've seen a lot but not for several years now. Anybody who does oddball genre-inspired comics should probably see it. It certainly influenced me. It's still great, still dryly funny and absurd. I suppose the whole "humanity versus computer" storyline is a bit played out. Not to mention that the "hard-boiled detective meets sci-fi" thing has been done to death, as well. And, watching it now, the "love is the answer" ending seems kind of quaint, especially for a film that was once considered bizarre or brutally avant-garde to some people. It's tough to be reminded of how idealistic people in the '60s were, especially considering how much they seem to be disdained now. But Alphaville has that sense of anger and the absurd - in this case about how willing people are to blindly follow orders. That's still relevant.

Do you prefer producing and publishing stories in serial form or all at once?

In a perfect world I'd be able to serialize all my stories. It's definitely preferable to me than doing one huge graphic novel over the course of a couple of years. I love getting the response from readers as episodes are released. I had that with both The Chuckling Whatsit in the anthology comic Zero Zero and with Mad Night (when it was called Reflection in a Glass Scorpion) in my own 12-issue comic Evil Eye. It was a perfect fit for me, doing these epic thrillers in installments. That's not really something you can do anymore in comics except online, which is what I'm attempting to do with The Bloody Cardinal. I'll post about two pages of that a week.

Your comics are filled with visual and literary references to earlier cultural sources (everything from Twilight Zone episodes and Mario Bava films to the Grimm brothers, Shakespeare, and Santa Claus) -- is this mostly just for fun, or is it important/useful for readers to catch the references?

Oh it's mostly for fun. I like feeling part of a creative tradition of artists and storytellers. I'm constantly falling in love with stories or images - I always have - and I have to express it in some way, or acknowledge the joy and inspiration these things give me. There's power in those old stories and images. If they enrich my work for readers in any way, that's fine, but you won't miss anything if you don't catch every obscure reference.

How much of your writing and plotting is instinctual, and how much do you plot in advance?

I have to be able to surprise myself to keep it interesting for both myself and the reader. I could never have every page outlined in advance and not waver from that. I know the plot and the motivations. But I have to be able to improvise, get new ideas and make changes as I go. I'll often be taking a walk and have a brainstorm on how to improve the next few pages. I may know how it's going to end, but the fun is in getting there. I know the exact last line of The Bloody Cardinal, for example. But I have no idea how many pages it's going to take to get there yet. And when I do get there I may decide not to use the line after all. The important thing is to keep it feeling fresh.

This may or may not be related to the last question, but many of the mysteries in your books are left unsolved -- do you generally know the answers yourself, even if you don't share them?

I think the mysteries that need to be solved are solved. I don't cheat with those, though sometimes you have to look close. But there are always some mysteries that can't be solved. Leaving certain mysteries unsolved, I think, is an acknowledgement of the cosmic or the unknowable and can feel powerfully unsettling. You have to be careful not to overuse that though. I think most of the time I leave enough information for the reader to fill in the blanks with their own imagination.

Some critics argue that horror is essentially conservative in nature? Do you agree? (I don't mean to presume you consider your own work horror, as you might not...)

I'm the first to admit that my work is hard to pigeonhole. It's not really strictly horror, though there are elements of horror. But there are also elements of mysteries and thrillers and old-time pulps and serials and B-movies as well as humor. There is no one marketable word to describe it accurately, unfortunately, I'm sorry to say. I'm lucky that any of my readers have ever found me at all. And I'm eternally grateful to the folks at Fantagraphics for trying to sell something as head scratching as whatever it is I do.

But to answer your question - certainly horror lets us explore thoughts and feelings we might rationally find taboo or shameful or reactionary. It's a safe way to explore fears, many of which might be conservative in nature: fear of strangers, fear of the unknown, fear of science and so on. But scary stories are good for helping people deal with their fears. They allow us to imagine our strengths in overcoming adversity and danger. Fear is a primal thing - you can deny it or rationalize it or try to suppress it, but it's better just to admit it's there and expose it to the light.

I think there is also a type of horror that is not conservative, but rising from guilt. In this country sometimes it's hard to believe how long we've been in denial about native americans and about slavery, not to mention what we've been doing to the land itself. I think the collective guilt and horror has begun to sink in, especially in younger people, and it's freaking people out in ways they don't even recognize, but feel on a primal level. Some are in completely unhinged denial that we could have ever done anything wrong. But more sensitive types may be worried that our karma clock is running out. You can see it in all these movies and books about zombies and bleak futures and the end of the world. There is the uneasy feeling that somebody has to pay for the sins of our great-great-grandfathers.

Do artists have moral responsibility? Horrific art in particular is obviously fraught with potentially offensive imagery in multiple ways -- are there any particular guidelines you have set yourself?

If I ever think about how any of the work I do might upset a child or any sensitive type -- that's an awful feeling. I've had to write a couple of letters to younger readers explaining certain events in stories that were upsetting to them and I always stress that it's just a story and that they can continue the story in their own mind and make up whatever changes or endings they want to. It's all make believe. Friends have to remind me that people - including kids - love to be scared and know it's all just pretend. I certainly knew the difference between real life and scary stories from a very early age. But I actually once made a little kid cry by telling him a spooky story. He was the nephew of one of my exes and we were watching after him and telling him stories and he listened to my scary story about a monster who lived in a cave, then suddenly burst out crying. It was awful. I've never stopped feeling horrible about that. I also remember being extremely upset myself by an EC comic, reprinted in one of those Ballantine paperbacks and which I was probably too young to read. It didn't scare me, it just depressed and disturbed me on a level I had never felt before. It was so bleak and cruel. I couldn't sleep and went down to the kitchen in the middle of the night where my mom was also still awake and sitting at the table smoking a cigarette. That human connection and small talk was enough to reassure me and I went back to bed. And despite what Dr. Wertham might want you to believe, that story didn't make me run out and kill people, it made me want to be kinder to people because life is so horrible. Take that, Wertham!

With which of your stories or books do you feel you most successfully achieved your artistic goals?

Oh, maybe The Chuckling Whatsit. At that time I was pretty proud of it. It got some good reviews but I don't know if a lot of people knew exactly what to make of it. It was pretty unapologetically genre - a mystery horror thriller - when most other alternative cartoonists were trying to distance themselves from genre stuff and write the great American graphic novel or doing Mad magazine style humor. As time has passed it seems to have acquired a certain respectability in some quarters, or so I hear. But I think I only kept making more comics after that because I felt I had to keep trying harder. It sold slowly but steadily over the years, which a lot of my books do. They don't exactly ever set the world on fire when they come out but people seem to keep "discovering" them over the years and buying them. And if they like one sometimes they'll buy more. And thanks to online book sellers I don't have to care if comic stores aren't restocking them (which probably few ever did).

In the TCJ interview I mentioned earlier, you expressed admiration for the plot formula used by Lester Dent in creating the Doc Savage stories. I am sure you have also heard of Edgar Wallace's famous "plot wheel." In some ways, these don't seem so dissimilar to techniques used by Surrealists, Dadaists, Brian Eno, and many others. Have you ever used similar devices in creating your own works?

Absolutely. Long ago I made up my own version of that famous "Oblique Strategies" deck, writing down situations, places and things on hundreds of file cards. That kind of thing is helpful for getting the ball rolling or getting unblocked if you're stuck. But the last thing I want my comics to be is totally random. If you need to get the creative juices flowing or let fate take your story in a direction you hadn't planned on, it's just as useful to flip through old notebooks for ideas you haven't used or go to the library or used books stores and browse through books. It's amazing how many great and original ideas there are in fiction that still haven't been discovered by Hollywood or become cliches.

I know The Bloody Cardinal has just started, but is there anything you would like to say about it for readers who might like to follow along? (I noticed that a similarly cardinal-headed figure makes an important appearance in your early story, "My Father's Brain".)

The Bloody Cardinal is a tale of mystery and intrigue that anyone interested in such things can follow online. The story unfolds in a way that is similar to The Chuckling Whatsit and Mad Night, with various characters and mysteries introduced along the way. In fact there are some deliberate echoes of The Chuckling Whatsit in some little details. And yes, the Cardinal has shown up before in some of my older works, maybe just a cameo or in the background. Now he gets his own book! I did have to change the name from The Cardinal (which had already been trademarked by a cartoonist for his online strip) to The Bloody Cardinal - which actually suits the character better anyway. It's an echo of those old German Edgar Wallace krimis like the The Sinister Monk or The Black Abbott. Or one of those Italian giallo thrillers with an animal in the title. And since both krimis and giallos are an influence, I'm actually happy with the change.

The first section is the depiction of excerpts of a diary, belonging to the title character, who is an unhinged master criminal who may or may not be dead. The rest of the story begins in Part Two where a number of characters are introduced who may or may not be involved in a series of murders and the missing diary. I promise it will all make sense - unless I'm hit by a bus before I can finish it. In which case I encourage readers to make up their own ending!

Your most recently published book is Violenzia. Can you tell me a little bit about what you were trying to achieve with the stories about the title character? She seems to be a bit more of a wish-fulfillment figure than you usually depict (in terms of her invulnerability, etc.).

I guess "wish fulfillment" is as good a description as any. The whole concept of superheroes - going back to The Shadow or The Spider in the pulps where they were a bit less coy about it - comes down to sorting things out with a little (or a lot of) violence. If you're stuck living in a world that seems more confusing and irrational everyday, you wish there was a way to sort it all out. So this is a modest fantasy about sorting things out, just basic pulp-style. It's not just a conservative fantasy - it's a very human fantasy for anyone who feels powerless or oppressed by things they can't control or understand. It's the primal desire to break out of invisible chains. It's not exactly rational thinking, but that's what fiction is for. And if only more people would work things out through fantasy instead of real life violence, we'd be a lot better off.

I was inspired by His Name is ... Savage, a very violent black-and-white comic magazine by Gil Kane from 1968, a year in which people were feeling a sense of troubling upheaval in society similar to what some may be feeling today. It was disturbing and cathartic at the same time, in the way a movie like Point Blank from 1967 also was. And in fact Point Blank has a semi-mystical vibe mixed with violence: a man (with only one name, Walker) somehow returns from the dead, takes his revenge, then disappears again. So those were the kinds of things that inspired the two Violenzia stories. In fact, the original title was going to be Her Name is Violence. It's also the result of a lifetime of reading about secret societies, conspiracies and magic. (I'm one of those people who would like to believe in those things more than I actually do). The idea is - there is another, hidden world behind what we see, where forces of chaos and destruction have always been in conflict with forces of balance and harmony. The title character is an emissary of the second group, summoned occasionally to sort things out on this plane of existence. And why be coy about how she'll sort things out? It's right in her name. The forces of evil can never be completely defeated, but small battles can be won. As a character, Violenzia is kind of an enigma, but she's tenacious and clever and fearless - and I tried to give her a glimmer of personality which I hope comes through, even though she's only got one line in the entire book.

That book also features "Forgotten", a short story that reads almost like an illustrated prose poem, which seems to present a rather cynical view of human history. What inspired it?

Some of my earliest short comics were fiction with first person narration. That's pretty common in comics now, as it's always been in fiction of course, but it wasn't back then at all, to write absurd or fantastic stories in first person. If people wrote in first person back then in comics, it was assumed to be autobiographical, for the most part. I was just always having fun with that, putting "myself" in crazy scenarios. So this was kind of a return to that kind of fiction. Those stories were always kind of dark, but they were about my own personal anxieties, really. I'm older now and my own problems seem trivial compared to the dysfunction of the world and humanity. Hate is here to stay and the peace and anti-war movements of the past have been laughed off the planet by the right and left alike. We've dug our own grave and now we have to lie in it. Or at least those were the kinds of thoughts I was having while taking walks and dreaming up this story. I guess the theme is not uncommon in my comics, though - which is, if you want to know how we got here, look in the mirror.

Are you still happy with the comics form?

Sure. Despite always wishing I was better, I'm grateful to the medium that's allowed me to create this kind of body of work entirely on my own, for better or worse.

And I'm glad I survived long enough to see really excellent reproduction of watercolor artwork - which was very rare when I started out. I loved the watercolor work of Gahan Wilson and MK Brown, but they appeared in glossy magazines where people knew how to make them look good. My illustrations looked fine in glossy mags, but no one in comics really knew how to do it at first. Even a magazine like Nickelodeon - sometimes they'd ask you to do the line art and color art separately but if you did, they never matched up. For years it was such a frustration. I think Maurice Vellekoop at D&Q was one of the first whose watercolor comics looked amazing. Now with the internet and better printing techniques it's really great, not only for me, but there are a bunch of cartoonists who do entire books using watercolors who are really good. I love seeing those.

One of the aspects of your comics that seems most distinctive is your use of abrupt transitions, which are often shocking and/or disorienting, and make the reader (or me, at least) often have to spend time rereading to understand what's going on. (One cartoonist who comes immediately to mind who does something comparable with the technique is Gilbert Hernandez.) Maybe this isn't a question exactly, but ... well, how much thought goes into the formal techniques you use? Are there any tricks you've developed that you'd be willing to share?

Those kinds of transitions are straight out of Dick Tracy, one of my biggest influences (and how I wish they would have retired that strip when Chester Gould, who was something altogether unique and irreplaceable, passed away). Gould was doing those cinematic "jump cuts" decades ago. My earlier one-shot comic book "Thirteen O'Clock" had narration text - like: "Meanwhile, on the other side of town…" which is the same kind of deadpan narration that the 1966 Batman TV show used, which is right out of comic books. It was intended to add to the arch, tongue-in-cheek nature of the story. But when I started The Chuckling Whatsit I dropped narration altogether and instead of looking at comic books, I looked at serialized stories from comic strips and used those abrupt transitions I learned from Gould. They can be disorienting but that's the effect I wanted because it heightens the mystery. I've used them ever since.

I had actually cut Dick Tracy strips out of the newspapers when I was a kid and even by the time I was in art school, I'd still be re-reading the few reprint books you could get back then, like The Celebrated Cases of Dick Tracy. Gould was a huge influence, a one-of-a-kind eccentric who somehow got his violent and grotesque fantasies printed on the front page of Sunday comic sections for years.

Final thought: in some ways, horror stories in film and literature seem more "scary" than they are in comics. I don't know if that's because comics are less immersive or for some other reason. I wonder sometimes if that's because comics are so obviously drawn, and so constantly remind the reader of the author's hand, that they have been created. By the same token, this may actually be a strength of comics for artists who are more interested in exploring aspects of weird stories more complex than the simple jump scares of affect horror... Have you given any thought as to what you can accomplish with your kind of story in comics that can't be achieved in other media?

It was rare, but there were some comics that scared me as a kid. I think maybe until I was in my early teens, I could get scared or shaken if the story happened to hit the right (or wrong) spot psychologically. It's very personal. If I tried to explain a comic that shook me up to someone, it might sound ridiculous to think it would frighten anybody. And as you get older, you wonder how you could ever have been scared, but it somehow hit you at the right place and the right time. I was once trying to discuss the positive aspects of being scared as entertainment to a friend who hated anything scary and I remember trying to keep it light by showing her a photo of the creatures from Invasion of the Saucer-Men, which are notoriously silly-looking. But she surprised me by saying she found the photo very disturbing and scary. And I realized she was reacting just as much to the idea that anyone could make something that looked so weird as to the creatures themselves. That's what's so interesting about horror, it hits you on an unconscious level. It's hard for me to talk about because I never set out thinking up ways to scare people. My thoughts are more about how I can lure people into mysteries that they'll want to follow. As the artist, my concern is just being receptive to what might disturb me and allowing those dark thoughts to flow, so I can pass on an atmosphere of intrigue and surprise to readers. The rest I have to leave up to the critics and psychoanalysts.