If I’m going to write about Saint Seiya—and I feel I have to now that Masami Kurumada’s landmark 1986-90 series is widely available on the Shonen Jump app after languishing out-of-print for ages—then I’m afraid I have to resort to writing in the first person. It’s not a prospect I relish: I have always been suspicious of confessional criticism, of the personal review and the gonzo feature piece, and so have always shied away from any style that would center extended discussion of my self. It’s a tenuous and in some ways self-contradictory proposition, I realize: if in my work I shy away from foregrounding my personality for fear of eclipsing the work in discussion and leaving the reader with an impression of nothing so much as a narcissistic self-portrait, by minimizing my own presence I run the danger of selling my opinions as something somehow untethered from all my little peculiarities of sensibility and personality. As something somehow “objective.” “Correct.”

Yet what strikes me as more dangerous is everything underlying the assertion of those writers who would sell their stance as bitingly, searingly, truly honest. “This is me, unvarnished and vulnerable, stripped of buffering anonymity,” crows the courageous essayist, as if this technique wasn’t the very basis of the con man’s trade, the very term they derive their title from; “Only with your confidence guaranteed can I begin to bare myself wholly,” they offer, even as with each and every assertion of their earnestness they take the credulous reader for everything they have. What’s lost may not be as concrete as the watch fleeced, the checkbook purloined, or the purse snatched by the more traditional grifter, no, but for its abstract nature what the literary fraud robs us of is all the more insidious. The writer who would offer you a stance at a distance is the writer who trusts you to recognize the gap between opinion and fact, whose pose is so apparent it hardly needs stating; what they offer is no saphead objectivity but an opinion arrived at by deliberation, their argument and authority derived from a considered aesthetic standpoint. The writer who insists on the utter sincerity of their stance, though, who mewls about the earnestness and enthusiasm of their dissertation, isn’t appealing to an aesthetic authority, at least not as they present it. Instead, they claim, it is an ethical authority they argue for: if misdirection and deception—fundamental aspects of any critical project, speaking as it does with authority even while operating from an inescapably limited viewpoint—are inherently immoral, then, they insist, honesty and all its corollaries must, by negation, be free of all artifice and so, inherently, something somehow moral. Something somehow “good.” “Correct.”

Heard through this filter, the discussion of any artistic project becomes discussions about the wholesomeness, the positivity, the goodness of art and what values it instills in readers. Consequently, they develop into discussions about the moral value of the people expounding, the art nominally in question reduced to nothing but a tool for self-promotion and litigation. It’s a convenient delusion that both flattens the possibilities of art by denying the looseness necessary for play and experimentation and ambiguity, and overlooks the truth that the self is as much a fiction as any comic, authored as surely as any novel, which seems fitting for a tack uninterested in art as a matter of taste and sensibility. To admit that their preferred method is hardly some unvarnished look at the truth but a carefully fabricated narrative—in short, as much an aesthetic construction as the so-called “lies” they denounce—would be to cede both the moral ground they’ve fought so hard for and the prestige it buys them, which in turn would be to admit that this has never, in fact, been about the art or even art’s morality but about nothing so much as the author’s gaping and vacuous ego.

Unfortunately, when it comes to Saint Seiya, it is impossible for me to discuss it without deferring to my own gaping and vacuous ego. Because I never just liked Saint Seiya; Saint Seiya I loved. Considered it the only thing I would ever identify as a fan of. Not an enthusiast, not an appreciator, not even a stern and stoic enjoyer, but a soy-faced fan, given to howling and breathless proselytizing about the adventures of Seiya and Shun and Shiryū and Hyōga and Ikki the way that fans of Star Wars or Harry Potter or Nintendo franchises or any other pop culture detritus are given to howling and breathlessly proselytizing about the franchise that imprinted on their as-yet-unformed brains; there is no other franchise or property from my youth for which I feel the fuzzy nostalgia that mere mention of Saint Seiya fills me with. Because at a time when my fellow teenage weebs would spend every lunch hour dissecting the various qualities of the Shonen Jump property currently occupying the national nerd brain trust—Rurōni Kenshin or Naruto or Bleach or Death Note or whatever was else cresting the wave of the mid '00s manga surge at that particular moment—I was busy campaigning for the undeniable superiority of Masami Kurumada’s global phenomenon: I organized a role-playing group of fans on Facebook, lobbied my reluctant bandmates in our god-awful garage band into learning “Pegasus Fantasy,” tricked friends who trusted what they considered my otherwise admirable musical tastes into suffering through the Saint Seiya soundtrack as we drove out of town to catch a concert before our parents realized we were gone, spent hours describing to anyone dumb enough to listen every exhausting detail of articulation and design of whatever Myth Cloth figurine I had scrounged up enough allowance to buy. Even when shipped off with a few dozen classmates on a compulsory mission trip to Mexico, I used our weekend excursions to nearby Mérida not to scrounge up schwag or suck down alcohol or chase after a summer fling like my classmates, but to go plumbing through bootleg DVD outlets in hopes of finding copies of the new-even-in-Japan Hades OVAs.

But while the adventures of Seiya and his fellow Saints may have been a global phenomenon, in the United States—always set apart from the world by a pig-headed exceptionalism—they hardly registered. In retrospect, it was a hopelessly uphill battle: the gruesomely edited Knights of the Zodiac broadcast to American audiences in 2003 reduced the anime to the butt of another in the endless series of jokes about American censorship, effectively ending the conversation before it could even begin, which in turn condemned the manga (still an uncertain pocket of publishing in the early '00s) to a similarly premature burial. Not that it ever had an honest chance: where the contemporary Shonen Jump titles it was competing for attention with were modern and cool and mature—their attitudes punkier and ostensibly anti-authoritarian and ripe for representation on Hot Topic t-shirts, their art styles more polished, their stories centered around heady topics like the moral dilemmas inherent in war or the ethics of playing God—Seiya was hopelessly square. The story of a group of orphaned youths, including the titular Seiya and his peers, who don magical leotards and tiaras called “Cloths” that instantly evoked Power Rangers, recalled uncomfortably through its superficial elements the childish notions that teenage manga fans of the mid '00s were eager to put behind them.

Doe-eyed and round-faced but broad-shouldered and squat, given to exaggerated comical postures and super-deformation in moments more lighthearted, the cast of Saint Seiya often looked like they were drawn in deliberate homage to Osamu Tezuka when they didn’t look like Trolls dolls. And yet a page or even a panel later might find Kurumada transitioning into a baroque and romantic style—all willowy pretty boys crying dazzling, sparkling tears while holding the corpse of a loved one and posing against a floral backdrop—that recalled no other artists as much as shōjo mainstays Riyoko Ikeda and Moto Hagio. The series’ tone is similarly androgynous: for all that Saint Seiya is a nekketsu-style story devoted to showcasing muscular men talking shit and pounding each other into paste in an endless succession of battles, much of its character development hinges on beautiful men declaiming at length about their feelings for each other, and much of its plot hinges on developments, like sudden resurrections or the existence of identical evil twins and evil split personalities, pulled straight from soap operas: it seems little accident that much of the yaoi boom of the late '80s is directly attributed to Saint Seiya’s runaway success. But if at one time Seiya and his pretty boy cadre had set the hearts of Japanese fujoshi pattering, by 2004 they seemed positively passé compared to the angst-ridden emo-adjacent stylings of brooding heartthrobs like Naruto’s Sasuke Uchiha and Death Note's Light Yagami. Too queer for the teenage American male, too nerdy for the teenage American girl, too dated for anybody, Saint Seiya looked ludicrous even by the dorky standards of nerds the country over.

The larger sweep of the narrative did little to dissuade that impression: dragooned into a lineage of so-called Saints who serve the goddess Athena (recently reborn as Saori Kido, spoiled heir to a Japanese corporate mogul’s empire), Seiya and company battle for truth and justice against a weekly rotating roster of villains that includes numerous traitorous other Saints and Greek deities, all cobbled together into a loose cosmology that Kurumada seems to have assembled from sources as disparate and dorky as Desmond Davis’ Clash of the Titans, Mahayana Buddhism, and a cod Catholicism that posits Athena as an all-forgiving, boundlessly loving divinity served by a Pope and locked into eternal struggle with more nefarious gods, such as the genocidal Hades and Poseidon. Even Cosmos, the internal energy source whence the Saints derive their power, feels as if it was named for the Carl Sagan television series, given how much the explanations behind it sound like warmed-over interpretations of the famous science writer’s pseudo-mystical stylings. “Your body,” a young Seiya is told by way of explanation to the reader, “is a mini-universe born from the Big Bang! True [Saints]1 can generate superhuman power by causing the mini-universes within their own bodies to explode... make your mini-universe explode! And your blows will be like a shower of meteors!!”

To drive the point home, rarely does Kurumada choose to show battles as a carefully choreographed exchange of blows dictated by spacing and pace. Instead he opts for a procession of double-page spreads that showcase the characters' many, many signature attacks against backdrops that consist almost entirely of xeroxed images of nebulae and quasars and stars, leaving battles feeling oddly bloodless despite the many gallons of gore spilled in each and every encounter. It made no sense, my friends argued, that the characters claimed that an attack known as the Athena Exclamation’s “power rivals that of the Big Bang... but focused on a single point” when it could barely blow up a single grove of trees, or that characters boasted again and again of moving at the speed of light but still took 12 hours to run up 12 flights of stairs.

I didn’t mind. In fact, I relished this hysterical approach to storytelling. There was in all the messiness and melodrama a poetic element—a romanticism—distinctly absent in so many of both Saint Seiya’s successors and its contemporaries that spoke to me in a way that nothing else did or could. It would be cute and clever to argue that I was sophisticated enough to appreciate Saint Seiya as some kind of camp classic. It would also be a lie. The forum-goer who introduced me to the series sold it as “the soccer of manga,” beloved the world over for its elegant simplicity, and I felt honored like all these other discerning readers to appreciate a story that had done away with much of what I considered insulting in contemporary shōnen artifice. I was at a time in my artistic development where, as a desire for more and more complex works of literature and film and music developed, so did a proportional disdain for pretense in pop entertainment. In the face of the fine-spun prose and lyrical political fables of José Saramago or the tormented spiritual yearning of Herman Melville, how could I take seriously the too-broad, ahistorical philosophizing of Eiichirō Oda or the flimsy angst of Tite Kubo? It wasn’t absurdity and glamour I disdained; if anything it was exactly these excesses that redeemed trash, and Saint Seiya was undeniable garbage - stupid and brash and gauche and mindlessly, endlessly entertaining. By contrast, what rankled me more than I could say was to turn on a movie or flip open a comic that seemed ashamed of its low-brow status and in apology tried to make an appeal to the reader’s moral and philosophical sensibilities, as if unique art, an idiosyncratic voice, and inventive composition were deficits, deceptions to be balanced by something ostensibly more sincere. The truth is that the real deception was elsewhere: for all that the characters in Naruto and Bleach and Kenshin spent lamenting their fate as super-powered bad-asses and yammering on about their desire to address injustice, nobody was fooled. Readers were returning week in and week out less because we were moved by Naruto convincing a hardened war criminal that killing and torture were bad, and more because we wanted to see ninjas perform dazzling acrobatics while spitting fire at each other or samurai crossing swords that just so happened to level buildings in the wake of all that slicing.

Saint Seiya offered no such excuses; it would surprise me not at all should I learn Kurumada took some level of inspiration from Steve Ditko’s Mr. A. given how unambiguous his disdain for moral equivocation is. Absent are villains defined by tragic backstories and some sympathetic trait; instead, Seiya and company’s foes are characteristically sadists who use a conveniently constructed moral rationalization to justify their cruelty; lazy cynics who have grown so comfortable with their position of authority they take it as divine right; or well-meaning but hapless dupes who lack moral imagination enough to wonder if the assassinations and drubbings they’ve been thoughtlessly dishing out on children and adolescents might not, in fact, have been issued in good faith. “Maybe a few brats got splattered in the crossfire when I was destroying my enemies.... As in any war, a few civilians get killed. Bombs go awry,” sneers the absurdly named Death Mask Cancer;2 “I believed that all human beings fight only for themselves... I believed that those who had power, those who were victorious, were qualified to declare themselves just,” admits the once-haughty Capricorn Shura only seconds before the righteous Shiryū puts pay to his self-serving dissembling. While no villain is ever beyond redemption—the final arc, which sees Seiya and company descending into Hades to prevent the dark god’s imminent resurrection, hinges on a number of former enemies making amends for their past cravenness—it is must first be earned after bloody and miserable and often fatal sacrifice: Kurumada’s Athena may be a goddess of love, but she is also a goddess of battle who has learned more than a few things about sin and punishment from the Catholicism her author cribs liberally from. Battle and its attendant ritualistic mutilation of the body is to be celebrated as the means by which grace is bestowed, not to be avoided or abhorred.

This is no mere artifact of the series appearing in a magazine aimed at children and teens obsessed with fantasy fisticuffs, though; it is the series’ overriding ethos, one it announces again and again. Across the span of 28 volumes, it is only ever the villains and the weak who lament the inherently barbaric nature of the whole enterprise. Among the core five central cast members it is telling that only Ikki actively begins as a villain (notwithstanding a subplot about Hyōga working as an assassin for the Pope that is dropped before he fights any of the heroes), and this because of the dehumanizing training he had to endure on the nightmarish-if-cartoonishly named Death Queen Island. It is his resentment and his inability to accept his fate that corrupts him, not the martial lifestyle itself. If more heroic Saints ever have complaints, it isn’t about all the fighting they have to do so much as it is about mismanagement: Seiya only ever expresses regret when he suspects that Saori is not, after all, the reincarnation of Athena, and that her grandfather (who, in a delightfully absurd and tragic twist out of Greek myth, is revealed to be the father of Seiya and 99 other orphans who were trained to become Bronze Saints) was a charlatan who organized all this conflict for his own profit. To be consigned to a life of endless bloodshed isn’t denounced as a curse: it’s a blessing, as holy a privilege as the rank “Saint” would suggest. When Seyia’s childhood friend Miho laments his ill fortune, stating that she feels sorry for him (“Ever since you were born, you’ve had to fight. You’re always covered with sores and dirt. All over the world, kids our age are enjoy their youth.”), Seiya pushes back, dismissing her concerns as frivolous:

I don’t think that’s all it’s cracked up to be. In a way, maybe we’re the lucky ones. To run around town and dance in clubs and wear fancy clothes... To go racing beside the ocean and through the mountains in a sports car, with a lover by your side... To live only for fun, chasing every new fad, to consider any hint of seriousness uncool... Is that what it means to enjoy youth? To be like everyone else, swept along by the currents of fashion? Maybe they’re the ones missing out... We’re different! We’re individuals in this vast universe. Isn’t that more fulfilling than being slaves to the will of the crowd? Our cosmos burn hot and unique. [Saori] said... that our destinies are determined by the stars we are born under. Some are born under lucky stars. Some are born under unlucky ones. There are all kinds of destinies... But whatever my stars were, I will live with honor and courage!! If I’m covered in wounds, I’ll be all the stronger when I’ve healed!

This he proclaims over the image of his body as big as the universe, all filled up with galaxies and nebulae, and in doing so makes clear that there is no higher an aspiration for readers than to differentiate themselves as special, unique, worthy through conflict.

As a high-schooler chafing under a sense of self-identity forged as much from my hope that I was some kind of precocious wunderkind destined for greatness—for ages it had been a point of pride that one of my favorite teachers, a recent college graduate assigned to us through an exchange program, had held me back after her last day teaching to assure me “[I was] going places”—and the immediate contradictions provided by humiliating bullying, misread social cues, fumbling romantic failures, and utter athletic inability, who escaped these daily reminders of inadequacy by doubling-down on reading and homework and writing, hoping that this focus would differentiate me from the crowd, Kurumada’s assurance that my disposition (reinforced by an idiosyncratic preference for Saint Seiya none around me shared) made me part of a morally righteous elect was all I had ever wanted to hear, and so became the moment where his series took on an almost Biblical importance to me. For it wasn’t just that I found my life in the present, with all its regimented structures and criteria, stifling: even the prospects guaranteed in the successful future I was supposedly set for seemed like a prison sentence. What worth was all the vaunted peace and security of a gray office job and a never-shrinking pile of consumer goods, I wanted to know, if it meant the horizons of my future were limned in by the exact same trite social pressures and shitty make-work tasks that had defined my youth? What good did it to do me to buy into a consumer culture run by and for people I loathed or break my back pursuing happiness by the standards of my peers when I had seen how cruel and petty and lousy the adults around us were, and was becoming keenly aware as I became more politically conscious of just how rotten leadership at every level was? So far as I was concerned, aesthetics were the only metric worthy of judging the world. Subjective a metric though they were, at least they were honest: the great artist knew their calling was in describing the world as only they could apprehend, not in offering some inarguable summary - and that calling to a higher kind of individual truth could only ever lead to conflict.

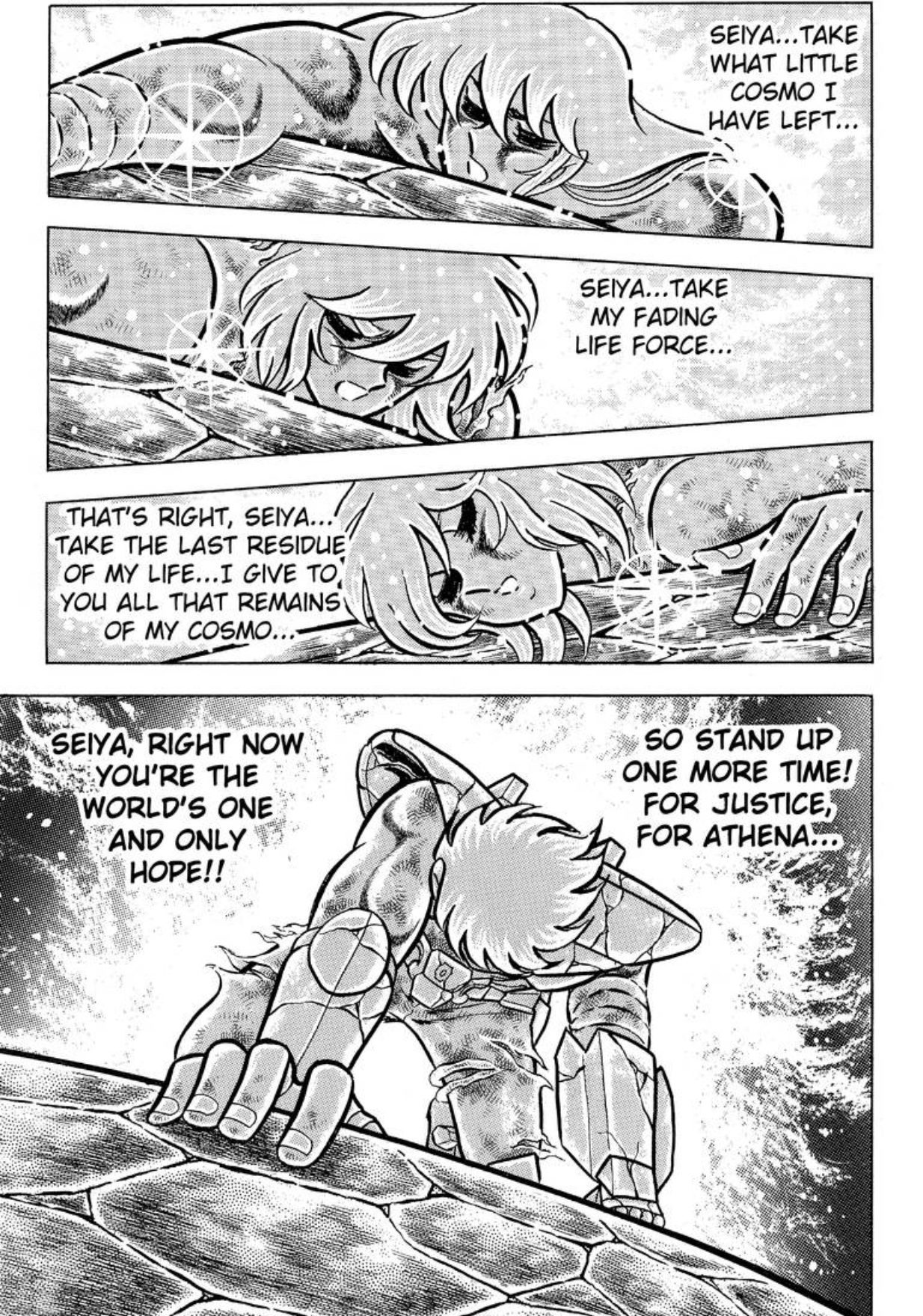

To find my worldview and my own anger justified by a story that met a number of my most cherished aesthetic criteria, chief among them honesty, only fed my certainty. After all, if art’s power resided in its ability to capture an author’s idiosyncratic worldview, then of what worth was art that floundered and flip-flopped and undercut itself at every opportunity? Where author Kurumada’s contemporaries and inheritors insisted that all of these super powers were a burden and that all the dramatics that provided us escape were not anything to aspire, really, that none of this was at all as fun or sexy or as popping or as beautiful as their exacting artwork demonstrated it was week after week, he had too much respect for readers: he wasn’t the sanctimonious Gold Saint using his position of power and privilege to write off his every contradictory action, the hypocritical parent assuring your differences and deficiencies were worthy of love one minute only to denounce you unambiguously as a freak two days later. He was, instead, the scrappy Bronze Saint who’d made his way despite the corrupt powers-that-be by dint of divine talent and unwavering moral compass; he was the kindly mentor who’d been there and seen it all, telling you that your freakishness was something to be proud of, something the others only envied. That the story ended with Saiya mortally wounded after sacrificing himself—the ultimate Romantic gesture—only confirmed my belief that Kurumada’s vision was one of the few honest in the game, and so one of the few worth preserving.

For the me now, though, returning to the series for the first time in over 15 years, I was baffled by the conflict between the fond fandom I had nurtured for all those years and a sensation that something had curdled in my time away. Make no mistake, Saint Seiya’s status as a classic should go uncontested. It is, for one thing, a perfectly paced palliative to the bloat that defines so much contemporary serial storytelling, a comparatively brisk 28 volumes in which none but the climactic fights lasts much longer than a chapter, no arc lasts longer than its welcome, and the world-building has been stripped down to a timeless, almost mythological sense that eschews the trend of more modern series that make glossaries just about a prerequisite for following along. Every bit of extravagance is saved instead for the art, particularly in those moments Kurumada seems intent upon fulfilling reader expectations that the Saints really are capable of moving at the speed of light or demolishing galaxies. Kurumada’s expressionistic approach to battle is a particularly welcome exception in a world where action comics have long forsaken his more explosive, iconic approach—near every attack is granted a full- or double-paged spread—in favor of a moment-by-moment, action-by-action panel choreographies so painstaking they feel pedantic. Perhaps it had to be this way: as the series progresses and evolves, so too do the designs of the Saints’ cloths, until by the end they are all such Rococo marvels it becomes impossible to imagine their wearers engaging in drawn out blow-by-blows, and so each battle often ends up feeling like nothing so much as a voguing contest. Every bit as elegant and simple as the phrase “soccer of manga” had once led me to believe it, Saint Seiya is ripe—and deserving—for reevaluation. Unfortunately, for all that I correctly identified as Saint Seiya’s charm, I was mistaken to interpret its simplicity as a lack of pretension. As an act of honesty. That isn’t to say Kurumada’s manga is pompous and overinflated; even the cartoonish boasts of the villains (“[T]hat was the Galaxian Explosion, which has the power to destroy the stars and planets of the Milky Way,” sneers the villainous Gemini Saga after unleashing an attack that looks to have done little more than blow away a small portion of a temple’s roof) possess a humor that suggests Kurumda is aware of how deliciously overstated this all is. The problem runs deeper, down to the series’ very philosophy, which is nowhere more accurately summarized or tellingly espoused than in Seiya’s pivotal monologue.

It’s funny: I have replayed and reminded myself of the sequence again and again since I last read it, adopted it as a mantra the same way certain Dune fans have adopted the Litany Against Fear. But the gap between our memory of art and the immediate experience of art is, as anybody who has had the warm bubble of nostalgia rudely punctured might tell you, gaping. Equally vast looms the gap between the image we had of ourselves in the past and the image we have of ourselves now: the Austin who would have once responded with fist-pumping vigor to that monologue and found in a kind of universal statement of defiance was an Austin who literally could not imagine himself with a girlfriend and so dismissed any possibility of romance as insipid; an Austin who was certain of his place in literary history, his future as an editor, and his ability to make a go of it as some kind of genius hermit. The Austin I am now is almost double the age of the Austin who idolized what Seiya’s rant suggested, though, and so can respond to this moment I used to adore only with a mixture of pity for the person I was and a small sense of pride for how it is I’ve changed.

Ironically, I imagine my past self would feel the inverse. By most standards, I imagine he would view my path as one life-long compromise: the career in publishing I doggedly pursued through a series of miserable setbacks and false starts fizzled out after years copy-editing Sudoku books and Bill O’Reilly hackwork led me to understand I would be much happier (and richer) shoveling dog shit. My fiction has gone unpublished, my comics forgotten where they aren’t simply unfinished, my essays consigned to a handful of niche (albeit supportive) publications; if I have any place in the history of American letters it is as a footnote, mentioned only for my appearance on a handful of Acknowledgments pages in titles I copy-edited or as the go-to pet-sitter to a circle of semi-famous poets who once moonlit as escorts. As if to prove my younger self's misanthropy correct, my decision to forsake my artistic vocation the better to focus on personal commitments has again and again proven disastrous: I have been engaged and moved across the country for a relationship only to be left for another man; I have found myself caught in a marriage that demanded more than I was ever ready to give; one of my closest college friends killed himself mere hours after reaching out to me for help, a tragedy I still blame myself for in large part.

Interesting as I might be able to claim my life has been, it is hardly legendary; by most accounts it reads as tawdry, venal, a cute party trick to trot out when I need to entertain guests or make a date laugh. I cannot imagine my younger self would see my path as anything other than a two-decade plan to frustrate my teacher’s prophecy that I was, in fact, “going places” and Seiya’s assurance that my Cosmos “burn[ed] hot and unique.”

And in many ways I am tempted to agree with his assessment. It would be a lie to say I’ve cut the knot of resentment and rage that’s so long been bundled up in my gut. Anyone even passingly familiar with the state of American letters knows how much success boils down (as with all things in this world) to connections and self-marketing; at least ego and vanity are two natural resources capitalism can ensure are infinite. Similarly, anybody who has paid a modicum of attention to the publishing industry knows how wildly exclusionary its hiring practices are. The first time you are turned down for a position as an editorial assistant after staying up until 6:00 AM to finish reading a manuscript and then report on it after a 12-hour shift, only to be passed over for a competitor the hiring executive described as “less adequate but more experienced and connected,” it’s a scar, a badge of honor to prove you’ve been in the shit; the dozenth time, it’s not even an insult so much as a universal law you finally have gathered enough data to prove as surely as Newton did gravity. Part of me wonders even now if the acceptance I’ve arrived at isn’t in fact a case of sour grapes meant to excuse my failures. That I wasn’t only one more job application, one more informational interview, one more day at work from escaping the assembly line of production to take a seat at the editorial table. Likewise, the frayed bonds I've left behind: had I simply communicated my fears more clearly, managed my resentments, forsaken my professional aspirations, could I have convinced my fiancé to remain? Had I held on to that phone call just one minute longer would my friend still be with me today? The fear that I have nobody to blame but myself for my current predicament—that I should, as my younger self rightly saw, have chosen artistic monasticism until the end instead of splitting the difference and saddling everybody and myself with the proverbial bill—is so great that I often have no choice but to convert it into anger and defiance and an assurance that some of what I’ve endured has been beyond anybody’s control. Our world is an exceptionally callous one, driven by markets of brute logic that can think of human life only in terms of value and exchange, and the simple truth is that by most metrics the vast majority of us are superfluous, our destinies as well as our desires mundane. Given the choice between my life—drab, rote, extraneous—and the fantasies embodied by Seiya, how could I deny the appeal of the latter?

Yet even as much as I am sympathetic to this judgment, I can never fully again inhabit the worldview once so core to my ego. All these wrinkles in my life have added, if nothing else, a texture that has shown me how flat was my way of thinking. It is difficult some days to accept where I’ve ended up and to square that with who I was and with the rapidly narrowing possibilities still open to me, yes. But there’s a peace attendant in knowing too how adaptive and malleable our conception of “self” is, a revelation that comes every time you go to bed thinking that your mistakes have unleashed the Apocalypse, only to wake in the morning and find that you are still alive. The world continues apace. I imagine this is the same bargain every failed would-be genius makes between their hopes and their resignations, shedding delusions of grandeur for a gentler worldview and a coddling mediocrity that espouses continued survival and change as its own kind of virtue, but I also know that the vast majority of us will never achieve the dreams we once defined ourselves by, and that it is impossible to hew forever to some perpetually more distant “ideal” identity that may never have existed in the first place. For all of my failures and compromises, there exists only one advantage I have above my younger persona: it is that I have read far, far more widely and with far more attention to detail than was ever possible in my youth, and so have context and history enough to recognize how uncertain was the foundation he built his identity upon. It is difficult after a life spent half in books to overlook how the million and one little techniques—structure, plot, intentional conflict, symbols lousy with the stink of meaning and relationships explained in terms of cliché psychological processes—used to lend coherence to our art are then used to paper over our infinite contradictions and our inexplicable idiosyncrasies and our unconscious impulses and call it all a “self.” We are not the person we thought we were, but then we never were: the self is fiction, one propped up largely by stories, which in turn are themselves retellings of older and older tales that pass down their own mistaken assumptions, generation after generation, as if they were inviolable gospel and not what a truly honest assessment would reveal them to be: lies.

There is a sequence in a late chapter of writer Tsugumi Ōba’s and artist Takeshi Obata’s Bakuman. where protagonists and artistic collaborators Moritaka Mashiro and Akito Takagi cross paths after the former departs a high school reunion dejected and slightly embittered after seeing how classmates and friends have changed over the ensuing years. “We’re different from the others, aren’t we...? All we’ve done since our third year in middle school is work on manga. We’ve hardly had any fun. I’ve never been to a mixer or karaoke. And since I started drawing manga, I haven’t been to the beach or gone skiing...” he mopes, eyes glassy. But after a pep talk from his partner (“All young men around your age go to the mountains and beaches with their girlfriends to enjoy their youth... but I have experienced a burning passion many times... I’m not like those guys who are barely sizzling. It may only be for a fraction of a second, but I’ll burn with bright-red flames.... And all that will be left afterwards is white ash...” ), Mashiro’s response is no longer colored by doubt. Together, against a backdrop of shooting stars, the pair shouts, “Yeah, we’re doing our best... we’re happy.... We may not have a typical young person’s life, but we’re leading a typical manga artist’s life of writing and inking! And that’s fine,” as if the sudden burst of enthusiasm and romantic cosmic iconography would be enough to make readers forget that the “typical manga artist’s life” as portrayed led Mashiro’s own uncle to an early, lonely grave, and put Mashiro himself into the hospital by the time he was 19.

I have long hated Bakuman. for many things—for its misogyny, for its stupid humor, for its psychopathic approach to art and industry, for its smug superiority—but most of all I have hated it for this speech; any time I have tried to explain my disdain for the series, I have always had cause to describe this as the one moment that perfectly encapsulates its most grievous vices. It’s deranged stuff, all the more so when considering the series was marketed by the weekly Shōnen Jump magazine in Japan as an inside look at the manga industry’s clandestine workings - the better to drag naïve hopefuls into the cutthroat world of mainstream Japanese comics production. It’s cynical and callous and stupid and contemptuous. Yet it is also, what with its allusions to the pettiness of materialistic youths, its celestial iconography, and its glorification of self-destruction, an almost-perfect echo of the speech Seiya delivers, which for so long I had looked to as a kind of anchor. To return to it and recognize suddenly that the only difference between the speech I had so long idolized and a speech I had so long despised was a matter of degree, not of kind, was to be dunked suddenly and without lifesaver into the arctic waters of cognitive dissonance.

The irony is that Takagi’s diatribe is not itself an allusion to Kurumada’s writings, but instead a paraphrase of another, longer speech found in another, older manga series: Asao Takamori’s and Tetsuya Chiba’s classic Ashita no Joe. Only, where Takamori and Chiba seemed torn between glorifying and cautioning against the physical and human costs of such reckless abandon, Ōba and Obata offer no such warning or qualifications, only full-throated endorsement. Forty years removed from Joe’s final and fatal battle, twenty years removed from the day Seiya threw his final punch at Hades, Bakuman. is the natural evolution of a narrative that has from the beginning flirted with the idea that nothing is more important in life than enthusiasm. Its authors recognized, just as I had in my youth, the hypocrisies underlying the genre they had already innovated with Death Note (the most openly cynical series imaginable) and began to wonder: what would it look like if they bothered to remove even the pretense of nuance from the genre? What if they doubled down on a series so all-consumingly earnest it could sell the idea of starvation wages and crippled social lives as professional aspirations worth killing and dying for? What would happen if they managed to demonstrate that sincerity taken to its limits was as cynical as anything else?

To dismiss as impossible the idea that a work—let alone a genre—might be both cynical and earnest at the same time is to misunderstand what earnestness means and what it is used to represent. Because earnestness is not a measure of the “honesty” of a work or a metric for determining some quotient of truth. Similarly so sincerity. They are poses, suggestions, affects that rely on an aggressive enthusiasm to stand in as an empty signifier for a “truth” they can prove in no other way. That Bakuman. and Saint Seiya more confidently espouse their philosophy than other mealy mouthed members of their class does not actually prove the rightness or consistency of their worldviews even if it does trick us into mistaking the self-assurance of their authors for proof of insight and dedication. They are the CEO insisting to his employees with a tear in his eyes that he truly does mean it when he says that he considers them his family even as he sacks half of them to keep his profit margins growing; they are the repentant husband swearing to his wife he loves nobody more than her with his head halfway out of the door and a condom in his wallet; they are the con man with his hand draped across our shoulder, smile plastered across his face, finger creeping into our wallet and assuring us that he at least is the last honest soul in this city. To point out the contradictions between their actions and how they present—to call them liars, hypocrites, as if to do so was to learn a demon’s true name and bind them—accomplishes nothing, because the parameters of their argument are only nominally moral. With closer consideration it isn’t hard to see that they have only ever been interested in using the sheen of ethics to mask that the appeal they are making is, in reality, an aesthetic one. That the universes of their stories are governed principally by systems of rewards and punishments that dole out grace to those who never swerve from their goal and condemns the rationalizers and compromisers no matter what their actual arguments are only reinforces this. Of course Mashiro and Takagi are eager to dismiss the growth in their peers as a kind of settling; of course Seiya would view his self-destructive lot as ordained by destiny, morally superior to the more mundane concerns of other adolescents, and that Kurumada would paint all of his villains as moral wafflers: to recognize yourself as a welter of contradictions and conflicting desires—and so as malleable—is to invite doubt and negativity. It is to contradict the fundamental principles of universes built entirely upon positive vibes.

Not coincidentally, this has long been the largest argument in favor of nostalgia: the fact that it seems all of our major cultural touchstones, from our comics to our books to our videogames to our movies are rehashes is if anything not a condemnation of these license’s fundamental hollowness, but instead a testament to their value. Surely nothing lacking in aesthetic merit would enjoy such widespread acclaim; surely nothing that makes so many so happy, so optimistic about themselves and the world could ever be toxic. Isn’t it enough that anybody the world over can pay a pittance to be instantly transported back, if not to a time and a place where they were safer, more innocent, more joyous, then at least to a mental state that makes them feel something of those Halcyon days? But again, the defense is purely a moral one—“How dare you impugn on somebody’s fun, you bully!”—and my objection to nostalgia as a predominant cultural force has always been aesthetic. What concerns me is not that this misty-eyed inclination is a lie. Lies are not by nature evil, they are in fact an essential component in everything from our pleasure to our sanity; we could not exist beyond them. What concerns me are matters more artistic: nostalgia is by nature a conservative impulse, defensive because it is aware that its object of adoration is doomed to obsolescence, and so views every possible replacement—everything new—as a threat to be smothered in the crib. It cannot abide criticism—or change, which it views as a kind of criticism—and yet has so little to offer in the face of these more constructive impulses that it inherently views them as a threat. So instead, it slyly changes the playing field and argues that its deception is no deception at all, but an honest, kind desire that only the true cynic could ever dare to question.

Much hash has been made out of what to do with this and about its influence on our minds. Least interesting are the endless litany of crank conservatives complaining about how we have fallen so far that we can only emulate past greatness (even as they crowed about how Top Gun: Maverick represented proof that Americans were hungry to return to the Reagan era). Less tired—because they are correct—but still trite are the indistinguishable hordes of leftist and BreadTube retreads of the concept of hauntologies and lost futures. It’s only those probing and ambitious critiques, like Studio Khara’s Rebuild of Evangelion film series and (to a less intelligent but arguably even more grandiose extent) Square-Enix’s Final Fantasy VII Remake series—that use the very cachet they’ve been awarded as cultural touchstones to challenge their complacent audience’s assumptions and hopes—that seem worthy to the task, because only they have the perspective of the traitor. Directly antagonistic, almost Brechtian in their desire to alienate audience from product, they hold out the promise of a perfect recreation of beloved classics updated to modern standards—the past perfectly preserved to match the evolving hopes and dreams of an audience that cannot face the truth that they, too, have changed, and so can never hold the same relationship to their favored artifacts—only to turn it back on itself at the last minute. “The past you wanted,” they seem to taunt, “is dead. In fact it never existed at all.”

While I had always appreciated this attitude in concept, it moved me little in practice. For one, I had found healthy ways to integrate both of these properties in my life long before the remakes came around, and so while I enjoyed their boldness I felt myself untouched in any emotional capacity. For another, despite my own deep nostalgic fondness for Saint Seiya, I had long withstood every new attempt to get me buy back into the franchise. Explaining to friends my enthusiasm for this dated relic was a delight; less so the trying and failing to navigate a million and one spin-offs, pseudo-sequel, retellings, reboots, side-stores and action figures. I had the original manga to read if I ever got tired of my memories of it, hadn’t I? And that was going nowhere. If ever I wanted to revisit it then I had little to do but pick it up all those old volumes again. In the meantime, I had the whole of art’s history and its immediate future to plumb, more work to engage with than anybody could manage, even given eternal life; what point was there getting caught up with childish things I had largely abandoned?

The truth as much as anything was that I never bothered with these cash-grabs for the same reason I never bothered, in all those years, to dig my old volumes of Saint Seiya out of storage: I realized what I would find there was only disappointment. Not the true extent of that disappointment, you understand; as I said before, no one can know how wide is the disparity between their idyllic memories and their mundane present until confronted with it. In a more abstract way, though, I could predict how disconcerting it would be to face down the specter of who I had been and the contrasts that had emerged in the intervening year. And had it not been for the coincidence of VIZ digitally re-releasing Saint Seiya at roughly the same time as a number of massive personal developments, I may have avoided ever taking up the challenge; it is a frightening thing to know that you have been consciously deceiving yourself for so long. As a close friend is fond of reminding me, “the self is a trap,” though not one with teeth that hold you in place and threaten to maim you if you move. It’s gentler than that, a fatalistic and self-enforcing loop: it’s the story we tell ourselves that insists we’re a coherent and rational creature whose desires and needs are all of a piece; it’s the nostalgia we sell ourselves that says there’s some part of us—pure and primal and rigid—that never can and never should change, and that any deviation therefrom is a betrayal; it’s the childhood obsession, the comic or the movie or the cartoon, so instrumental to our development we sanctify it, and in so doing move it beyond reproach. It’s the confession we hand to others, the script that assures them that this is all they’ll ever need in order to fully understand us.

Of course, though, they don’t. Won’t. Can’t. Just as there is no one artifact so capacious it encapsulates all of the world, and so coherent it allows no contradictions, there will never be a story we tell others or ourselves that will account for every one of our teeming shortcomings and hypocrisies. So it is that even while I’ve grown to accept that there are elements of Saint Seiya that it feels like I can hardly abide, elements that reveal a core ugliness, there is so much I adore. So it is that even while I’ve grown to accept that there are elements of Saint Seiya that feel like they are unimpeachably perfect, there are factors that make me loathe to recommend it. Because I never just loved Saint Seiya; Saint Seiya I hated. Because I never just hated Saint Seiya; Saint Seiya I loved.

* * *

- EDITOR'S NOTE: The translation of Saint Seiya on the Shonen Jump app appears identical to that of the 2004-10 print edition - which, for its first 14 volumes (through Chapter 50) credited Mari Morimoto and Lance Caselman with, respectively, "Translation" and "English Adaptation," and after that credited only Morimoto on translation. The app version also preserves the print edition's compromise title Knights of the Zodiac (Saint Seiya), and employs some localization measures for specific terms, e.g., "Knights" instead of "Saints." The text of this essay preserves the use of Seinto, or "Saint."

- "Mephisto" in the localization.