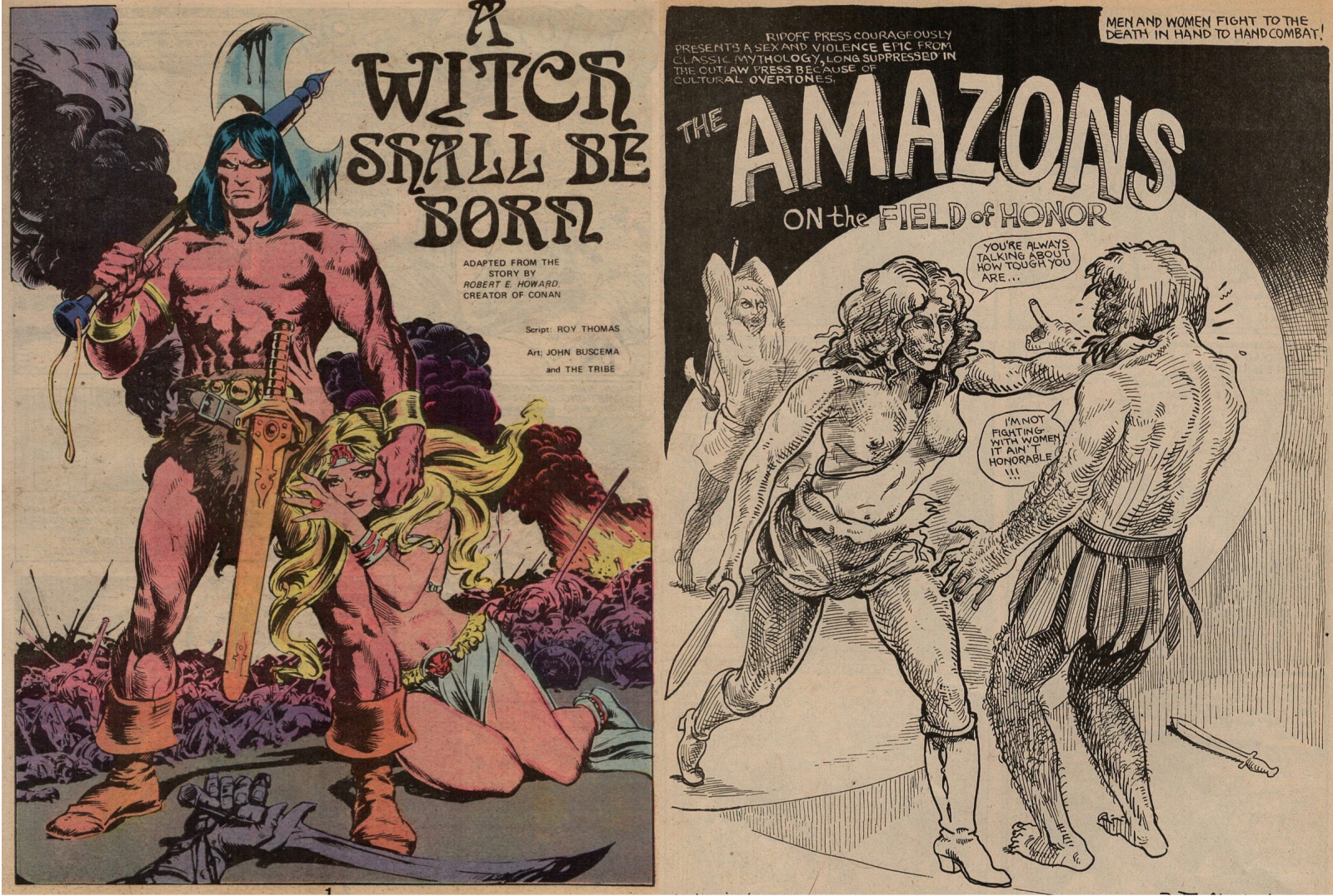

"A Witch Shall Be Born" from Marvel Treasury Edition #23: Conan the Barbarian (1979); penciled by John Buscema, inked by "The Tribe", written by Roy Thomas

If you had to choose one Marvel series to collect, here's the pick. Marvel Treasury Edition began as an effort to keep the Marvel superhero classics available—or at least recirculate them—in a massive tabloid format that maximizes the appeal of some amazing artwork. It's a treasure trove of great superhero comics that makes some of its publisher's biggest stories feel larger than life all over again. Seeing that stuff at double size in "old comic book"-style printing is a powerful experience. After a couple of all-Kirby collections and a Spider-Man grab bag, the title wooed an older audience in issue 4, a Conan issue that colorized Barry Windsor-Smith and Roy Thomas's epic "Red Nails" (1973). Free of the Comics Code Authority's seal of approval and full of gory, lewd content that makes no pretense of a school-age audience, "Red Nails" reads almost like Marvel was attempting to compete—or harmonize—with '70s underground comics like Slow Death or Skull Comics, in which artists like Richard Corben and Greg Irons played action licks over drippy, lysergic backing tracks to remarkably similar effect. "Red Nails" originally ran in Savage Tales, a black-and-white newsstand publication carrying the logo of Marvel's parent company Curtis, aimed at grown up stoners, bikers, nerds, and fuckups. This audience also provided the underground comics economy with a solid chunk of its cash flow, and gave the mainstream artists and nascent independent publishers of the late '70s a readership for work they'd dreamed of doing - that is, more of the same, but with blood and nipples and maybe a meaner or trippier edge. Conan ended up headlining a total of four Marvel Treasury Editions in five years.

In this issue, Treasury #23, Thomas and post-Windsor-Smith art partner John Buscema are really cooking. Robert E. Howard's lukewarm 1934 Conan epic "A Witch Shall be Born", the tale of Conan's crucifixion amid a civil war between a virtuous queen and her evil twin sister, is full of strong visual ideas the story's prose couldn't quite manage to sell. No problem for Buscema, whose work on the superhero comics that made his reputation was never phoned in, but pales next to the passion on the page in his brutish, prurient Conan stories. Full of towering figures and Dutch angles that amplify the torque and sinew of the action sequences, the comics version of "A Witch Shall be Born" (reprinted and colorized from The Savage Sword of Conan #5, April 1975) is Buscema at his best - especially in the many scenes of massed, hysterical figures engaged in battle or rebellion. It feels like a comics version of Cecil B. DeMille, full of monumental architecture and expressive overacting. Nearly as intense is the book's backmatter gallery of Conan pin-ups by artists like Gray Morrow and Alex Niño, which, like the best of Buscema's splash pages and his color-drenched cover, feel legit as posters at the size they're printed - extra copies were no doubt bought for dorm room walls. Different pin-ups show Conan both carrying off a sexy babe over his shoulder and getting dragged across the ground on a chain by a different sexy babe, ensuring that whatever your kink, you were closing this book with a boner.

The issue's high point is promised on the cover, which trumpets "CONAN ON THE CROSS!" Buscema attacks color-burned pages of his hero nailed in Vitruvian Man pose to a trunk of gnarled wood, bellowing in agony and rage, bared teeth tearing and rending at the vultures swooping in for his eyeballs. This sequence is truly special, the ultimate form of... well, something. A cheap high in its uncut form sometimes doesn't feel cheap at all. Buscema flexes harder the more lurid Thomas's adaptation of Howard gets - and it gets plenty lurid, outdoing the bawdy original text. Ink flecks of gore spray across pages, bordello scenes are composed with shameless abandon, and the repeated gang rape of the closest thing the story has to a female lead provides a recurring plot device that's necessary for the authors' pretense of morality to hold, since the "good" and "bad" characters are an understanding of consent away from being precisely as venal and barbaric as one other.

The inking of "The Tribe"—Tony DeZuniga's workshop of Filipino emigres, full of lush brush lines and zigzag hatching that calls back to Al Williamson or Joe Orlando—makes this book feel like a final form of what EC had endeavored to become a generation earlier: pulp fiction-derived, vividly imagined, masterfully visualized rotgut entertainment whose virtuoso artwork and high-flown language gleefully tiptoes the sidelines of that old chestnut about "redeeming social or artistic value". Here is a comic that landed at the perfect time - alongside Heavy Metal magazine and the horror-action books from the underground's last days and the early independent comics, kicking around the wastelands at the outer edges of what Americans then imagined the form to be, sometimes making mad, blind rushes into uncharted territory. Though this one doesn't do that, it's still got a charge. And yet actually reading it straight though, wolfing down this and the other stories in the book, empty calories panel by panel for 84 pages, is a good object lesson in why the medium as a whole needed ideals to strive for that went beyond pulp.

* * *

Amazon Comics (1972), by Frank Stack (as "Foolbert Sturgeon")

Part of what made the '70s a unique time in American comics was that mainstream publishers in an industry-wide downturn made a serious effort to develop revenue streams beyond superhero comics, just as the undergrounds leaned into genre content. Sometimes it was possible to pick a book from either side of the divide between mass media and autonomous experimental publishing and compare like for like, without parody or sarcasm or the comics code to muddy up things. Both "A Witch Shall Be Born" and Amazon Comics are seriously intended "sex and violence epic[s] from classic mythology," as Frank Stack's splash page at the top of this post has it. Using the faux-"historical" trappings of genre fantasy, both comics focus in on physical agony, sexual violence, and the dangerous place of women in a world where might makes right - in a milieu far removed from the seriousness owed these topics. Looking at the two comics side by side is a lesson in how the '70s mainstream and underground used differing elements of style to propel narrative - and how authorial intent on the one hand, and story content on the other, play tug of war for the right to dictate our experience of art.

Feeling a bit like the the reversed, identical photo negative of Buscema's and Thomas's thundering, pandering tale of sex, combat, and sexual combat in antiquity, Frank Stack's plainspoken story of the exact same things produces a savor as similar as kimchi is to Nutella. John Buscema's women certainly possess a kind of power, rippling across tabloid-sized pages with strong limbs, angry brows, and hair fanning out like fire - but not one of them can't be chained and broken by any random bad guy if it's what the story needs. Stack's book purports to tell the Homeric tale of Penthesilea, Queen of the Amazons, and her part in the Trojan War, as a retort to almost every other genre comic from the era's positioning of women characters as shrinking violets or food for the voracious appetites of evil men. Using straightforward, camera-on-the-ground framing and slangy modern dialogue, Amazon Comics strips a mythic tale of its mythologizing and upends what comics readers of the '70s (or now) expect from a swords-and-sandals saga.

Stack's battle scenes are as as impressive as any superheroic melee, but where artists of Buscema's ilk strain to elevate war and fighting to a realm of demigodhood, Stack rubs your nose in the dirt of it. Loosely cartooned and frenetically hatched with plenty of early newspaper comics-y squash and stretch, the barely-differentiated characters cram into panels twenty abreast kicking up dust clouds or square off in single combat against starkly drawn Hellenic plains. Whether minimal or filled to the gills, Stack's compositions and choreography are always perfectly clear and rapidly flowing. Some pages recall Jack Kirby's silent nine-panel grid faceoffs, while others feel like MAD marginalia scribbler Sergio Aragonés settling down and going for something more serious; fitting, given that "more serious MAD" is a decent reduction of the first-wave underground comics. Like Buscema on Conan, this too feels like a distillation of EC - but of Harvey Kurtzman's war and satire EC series, rather than the Al Feldstein-edited pulp ones.

The big difference is that while Buscema and Thomas are obviously committed, all they're committed to is intensity: a temperature of delivery that outstrips the weight of what they're actually saying. Stack has a point to make, one buttressed by familiarity with the Conanesque tropes most comics like this come adorned with. As the workaday Greek battalions upon which the comic opens wax halfheartedly poetic about the glory of physical combat and chivalry among fighting men, Penthesilea, eyes searing, scoffs "War is hell!" before wiping her boots with an entire Greek detachment whose codes of honor go missing when confronted with a woman adversary. The men here may work at soldiering, bound to friend and enemy alike by a masculinized "professionalism" - but the women live on a battlefield of necessity. Penthesilea's prowess is obvious and marvelous while never looking like anything but what it is: the scrabbles of a desperate figure in the dirt, denied the concessions to fair play that her male adversaries allow each other. As night falls and Stack's legions clock out for the day like so many factory hands, his Amazon queen doesn't hesitate to get some final shots in - before taking her unexpected reprieve with a mixture of bewilderment and relief.

The plainspoken quality of Stack's drawing runs into the balloons. Greek soldiers piss and moan about their less glorious military duties, the misogynistic shit talk of the bored an antistrophe to the zeal of the charged-up Amazons. The darkest moment Stack presents, the rape of a wounded Penthesilea by a group of (literally) backstabbing Greeks, framed straight on and full of blasé dialogue, feels uncomfortably close to the kind of thing that happens every day in empty subway cars or unlocked break rooms. Contrast this with the opening of Buscema's and Thomas's tale, in which a woman is consigned to a rape by invading soldiers which, in its particulars, is indistinguishable from what Stack presents - yet operatically framed as the classic "fate worse than death", with a slow fadeout on predatory leers, strings of spittle between gnashing teeth, and dungeon walls that echo with the trailing off of a helpless cry. Where Stack is sordid, Marvel is sinister, wreathed in all the dark glamor that word implies. Both artists match style to substance: Buscema draws on Renaissance painting's overblown physicality and film noir's manipulative angles, while Stack apes the full-figure framing of Greek vase painting and—in a callback to the early, proto-feminist Wonder Woman—bits of H.G. Peter's bouncy cartooning style.

There's humor to be found in both these books without looking too hard, if one is so inclined. Stack's squat or stringy figures, their amped up facial expressions and the action/reaction gag rhythms of his writing provide good reminders of why we call them comics. But Stack alludes to the absurdity of what he's showing without leaving behind the seriousness of what he's saying, while Buscema and Thomas are actually doing something funny, setting themselves on fire to wring every paltry ounce of grandeur from something equally absurd. This impulse to place upon a pedestal travails that are only "epic" because of their distance from reality is lampooned by Amazon Comics' epilogue. We flash forward to a college lecture hall, a scene of a furious male-led seminar on the Penthesilea cycle's possible origin in Homer's work. Human figures narrow to pipe cleaners with scarecrow midsections, panels bog down with word balloons, and the distinctions between the Homeresque, the Homeric, the Homerous, the Homerly, the Homeristic, the Homerical, the Homervian, &c. &c. are hotly debated. History repeats itself as a contingent of incredulous, exasperated women scholars combat the men's thesis of Penthesilea's inherent physical inferiority with their own right crosses and boot stomps. The tale thus ends, but it's impossible not to flip back to the beginning with a new appreciation of the scruffiness with which Stack invests his scenes of antiquity, given how far culture—in comics just as much as college—has gone to deify such stories.

Yet Stack's intelligent autocritique ultimately rings a little hollow. Both "A Witch Shall be Born" and Amazon Comics present a perspective that lasers in on war and rape as compulsively readable arenas of enthrallment, rather than ugly and unnecessary bullshit. Drawing styles aside, Stack's muscle dudes are as steroidally puffed up as Buscema's, his women's brawny frames as idealized. Like Conan's queens and tavern wenches, Stack's Amazons simply appear from nowhere to act as foils for the male warriors; we are in formation next to them as we begin our reading. The nudity-packed Amazon Comics is just as ripe for furtive browsing as the pin-ups of Marvel Treasury, depending on one's type. One line of Amazon Comics' opening splash page is a head-scratcher: it claims the Penthesilea tale has been "long suppressed in the outlaw press because of cultural overtones." I can't help but zero in on the in the "outlaw press" part rather than the cultural overtones: what?? Isn't the outlaw press for the long-suppressed? Could this be a subtle message that a "sex and violence epic" is too damn raw for the more equal society the hippie counterculture of underground comics at least paid lip service to? Is Stack aware there's a toxicity to his material that feminist framing can't completely varnish over? Does my man speak of... cancel culture? Or is he admitting that this kind of stuff is more naturally at home in something like... a Marvel Conan comic?

One can speculate, but time has rubbed things pretty smooth, to the point that from a certain angle these comics feel as similar as they are different. Half a century ago Conan was racked next to creator-owned genre books like Elfquest and Starstruck, in which talents like Wendy Pini and Elaine Lee dove deep enough into lore and worldbuilding to construct fantasy spaces that welcomed readers lacking male gazes. Amazon Comics, meanwhile, sat in head shop piles with Wimmen's Comix and It Ain't Me, Babe, where women artists like Trina Robbins and Willy Mendes eschewed metaphors that featured glistening nude ball-stompers. The winds of change blow through the longboxes, and acquaint men with strange bedfellows.