In 1963, things began to change for Saitō Pro. Its first major magazine commission arrived that year. It was for an adaptation of Ian Fleming’s James Bond for Shōgakukan’s teen monthly Boys Life. Other magazine gigs followed, most notably a series of short adult-targeted stories for Weekly Manga, also in 1963 (perhaps gekiga’s first foray into the world of adult comics), and an adaptation of the American television program Napoleon Solo for the children’s monthly Adventure King in 1965. The work starts to get tighter, more detailed, more polished. As the magazine commissions increased, so the work ethic at Saitō Pro began to change. Ishikawa Fumiyasu, who moved directly from the dissolved Gekiga Studio to Saitō Pro, has said the following about the early days of the studio: “Until 007 for Boys Life, Saitō Pro was like a cottage industry. Takemoto [Saburō, another longtime member] would help with other people’s work when he finished his own. The whole situation was very collegial. There was even collaborative works with the entire studio cast, in which Saitō would come up with stories, and the staff would be responsible for background and the characters.”

He is referring to the so-called “omnibus” projects that appear in Gorilla Magazine in 1963 and 1965. The difference between these, created amidst increasing mass print magazine work, and the tag-team experiments of 1962 are telling. The drawing and direction is now much more integrated. The distinctive hand of Nagashima is fairly easy to pick out in the 1963 “omnibus” stories, and one is helped in identifying Saitō’s own characters by the fact that they are the leads. The rest, however, is fairly homogenous: a singular house style had begun to gel. Another two-issue “omnibus” was organized in 1965, in celebration of Gorilla Magazine’s 40th issue. As in 1962’s “Cool Dudes,” each character of the story is attributed to a different member of the studio. Saitō of course gets the lead role. Yamada naturally gets the various female ones. But there is no longer a “director,” let alone a changing one – which is to say that there is no longer even the conceit of multiple people in charge. Small stylistic differences between artists are noticeable, but the only significant ones are between the sexes. The overall image is now one of integrated “teamwork.”

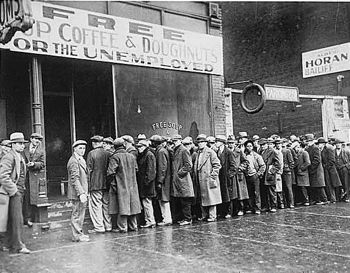

In retrospect, the 1965 “omnibus” looks like an end-of-the-year company party. The employees loosen their ties and get rowdy, drunkenly flaunting a little of their individuality in one last hurrah before hunkering down for the new year. And the next year was definitely a new year for Saitō Pro. In 1966, it published the 47th and final issue of Gorilla Magazine. The decline of the kashihon market had forced Saitō to close his publishing division (it would re-open as Leed in 1974). This was ultimately a blessing in disguise, for 1966 was also the year Saitō and his studio became regulars for Shōnen Magazine, and it was through the weekly that Saitō Pro began to emerge as the highly stratified and rationalized symbol of a newly industrialized Japanese comics industry. The end of the kashihon market and the temporary halt on self-publishing helped clear the way for the studio’s full integration into the corporate world of mass publishing.

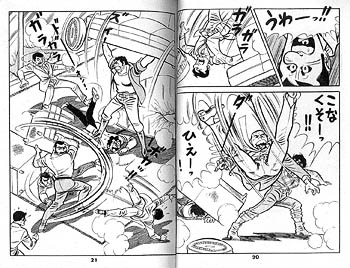

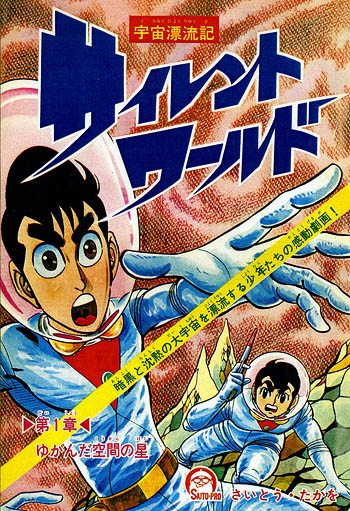

Saitō Pro’s first stories for Magazine are a grab bag of shorts ranging from the standard boxing and sword-fighting themes to riffs on Gregory Peck’s Moby Dick (now it’s a very big shark) and The Lost World. His first hit serial for the magazine was Silent World (1966-67), a rewrite of a kashihon title from 1963 about a team of trainee astronauts suddenly at sea in the outer unknown of space, where they have to navigate planets with shape-shifting atmospheres and mean armored aliens that seem to have immigrated into Saitō’s universe from planet Marvel. In 1967 appear the first of Saitō’s samurai stories for Magazine, culminating in Muyōnosuke, serialized between September 1967 and May 1970, and memorialized in January of its last year in “An Introduction to Gekiga” as Magazine’s representative gekiga.

In August 1967, just before Muyōnosuke began, Magazine ran a feature on Saitō. It was one of a series of interviews with the magazine’s top artists, filled with silly jokes and aimed at children, but illuminating nonetheless. In it, Saitō is introduced as “the man of the hour who has blown the new wind of ‘gekiga’ through the publishing world. A great man, he throws himself into his work with the fierce fighting spirit of a wild beast.” Some good-natured jesting is made of his rotundity: he calls himself Gorilla but emerges from the studio “kersplash like a hippo from the water.” Asked to define gekiga, he simply explains that as motion pictures are now called movies, the name manga is too old-fashioned for the present tense of narrative comics. Asked what the future holds, Saitō says, “I would like to expand my work through integrated production methods that have never been used before.” “You mean like the movies, where everyone’s strengths are used . . .” “That’s right. Instead of having the basic idea, the sketches, the layout, and the making of the story all the work of a single genius, you collect various people to work together . . .” Then Saitō’s brother, the studio’s manager, cuts in with a blueprint for Saitō Pro’s future home, a new building in Nakano. The interviewer calls it “a great four-story gekiga factory.” He adds that “there’s no reason for you to explain what gekiga is anymore,” the superior products of this “gekiga factory” will speak for themselves. Saitō can only agree, “Exactly. They can say all they want. This is the end for boring gekiga.”