Russ Heath, best known for the realistic clarity and human drama he brought to the war comics he drew for DC, Marvel, Warren, and EC, died Thursday night. Throughout his nearly 75 years drawing comics professionally, Heath was an artist’s artist who took few shortcuts. His deadline-flouting attention to detail was so ambitious that, whenever one of his jobs was delivered, editor Archie Goodwin reported, everyone gathered around to see what “that crazy bastard Heath” had done.

As a boy, Heath followed adventure strips like Terry and the Pirates, Tarzan, Flash Gordon, Scorchy Smith, and Captain Easy. He got into comic books on the ground floor, buying, at the age of 7, one of the earliest issues of the first comic book: Famous Funnies. He drew his own comic books, giving them the title Russ Comics.

Heath struggled in school, but his talent as an artist matured rapidly. He got his first professional job on a comic book (through an acquaintance of his father) when he was still in high school, aged 16 — but it wasn’t a Western. Between 1942 and 1944, he worked on Hammerhead Hawley, a series about submarine warfare in the North Pacific that appeared in Captain Aero Comics from Holyoke Publishing. Heath worked on issues #8, #9, #10, #11, #13 and #14, initially inking the pencil art of Charles Quinlan before taking over the penciling as well as inking. His faces were relatively crude — especially the propagandistic, monkey-like caricatures of the Japanese enemy — but his backgrounds were already grounded in realistic detail. The young artist also seemed to have an instinctive grasp of storytelling layouts.

In an interview conducted by Ken Jones for TCJ #117 (1987), Heath said, “I think the fact that World War II was going on when I was a teenager influenced me very much. I noticed the military hardware with an artist’s eye. I can still draw all the bombers and planes and small arms of most of the major powers’ armed forces.”

Heath answered the call of the real-world war by joining the Air Force while still in his senior year of high school. It wasn’t until 1947 that he was able to get his diploma and resume his comics career.

Between the war comics and the Western comics, Heath’s name immediately conjures images of sweaty, unshaven, violent, well-armed masculinity, but a surprising thing happened at Timely. It turned out Heath also had a knack for drawing female characters, which led to work on newly launched hybrid titles like Love Trails; Rangeland Love; Cowgirl Romance; and Reno Brown, Hollywood’s Greatest Cowgirl. Heath’s assignments during 1949 and 1950 included stories like “Heartbreak at the Rodeo”, “This Gal is Mine”, and “Aces, Bullets and Hearts”.

Beginning in 1951, Timely, along with other publishing lines owned by Martin Goodman, fell under the Atlas logo. Timely had focused mainly on superheroes, cowboys and romance — in fact, Heath, who rarely drew superheroes, briefly worked on The Human Torch with Carl Burgos in 1953. But with superheroes faltering in the 1950s, Atlas began to veer into other genres, trying Heath out on a variety of titles, including Adventures into Terror, Journey into Unknown Worlds, Suspense, Astonishing, Marvel Tales, Marvel Boy, War Comics, War Adventures, Young Men on the Battlefield, Adventures into Weird Worlds, Battle, Spy Fighters, Strange Tales, Combat Kelly, Man Comics, Girl Comics, Kent Blake of the Secret Service, Spellbound, Men in Action, Mystery Tales, Mystic, Combat, Journey into Mystery, Menace, Uncanny Tales, Battlefront, Wild, Marines in Battle, Crazy, Crime Exposed, Lorna the Jungle Girl, and many others. Heath proved he could handle whatever they threw at him, but it was also clear that the more rooted in reality a story was, the better it suited him. That predilection held true for his entire professional life and, for the most part, kept him out of the bonanza of superhero titles that dominated the last half of the 20th century.

Timely/Atlas had its ups and downs during the 1950s, sometimes steering plenty of work Heath’s way and sometimes cutting back, surviving on stockpiled inventory stories. During the down times at Atlas, Heath branched out to other publishers. In 1953, he drew a story for Lev Gleason’s Boy Loves Girl, but two other jobs formed editorial connections that would map out much of his future career. In 1951, he did a six-page story called “O.P.!” for the first issue of EC’s legendary Frontline Combat. It was the only work he did for that title, but his association with Frontline Combat editor Harvey Kurtzman later led to jobs on Mad, Humbug, Help, and Trump, and eventually to a role in producing Little Annie Fanny for Playboy. And in 1953, he did a handful of single-pagers profiling the denizens of prehistory in Animals of 1,000,000 Years, part of St. John’s 3-D line. The title was edited by Joe Kubert, who would later oversee Heath’s war comics for DC.

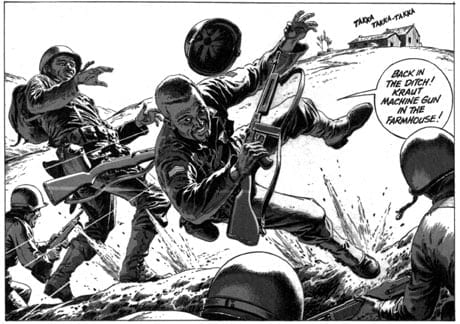

The start of Heath’s decades-long run at DC was a 1954 story called “The Dry-Run Sub” in Our Army at War #23, a return to the military submarine genre that had begun his comics career. His command of the look, atmosphere, armaments and logistics of WWII combat made him a go-to artist for DC’s military titles, including Star Spangled War Stories, All American Men of War, Our Fighting Forces, G.I. Combat, Our Army at War, and Showcase: The Frogmen.

Kanigher established a formula for his plots: morality tales of heroism and irony interspersed with explosions. Heath’s dynamically composed but unexaggerated art gave the stories a core honesty and physical believability. Heath’s soldiers were tidier than Kubert’s ragged G.I.s, but they shared a look: haggard eyes and permanent stubble. The essential conflict of the stories was there in the visuals — American democracy represented by unkempt working-class Joes, exhausted but stubborn, set against the perfectly groomed, immaculately uniformed schoolyard bullies of Aryan fascism.

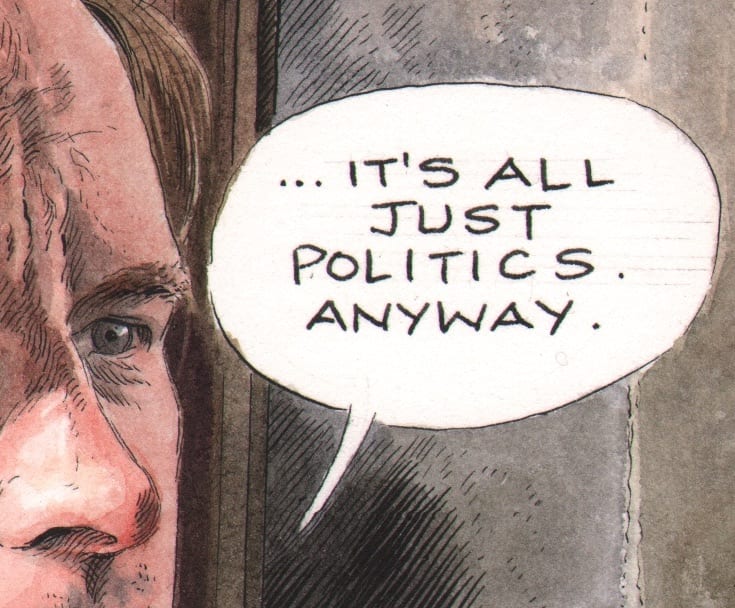

Heath’s art was so emblematic of war-comics imagery that prominent pop artist Roy Lichtenstein famously (or infamously, depending on your point of view) lifted Heath panels from All American Men of War #89, blowing them up to display an impression of Ben Day dots, flattening the surfaces, reducing the shading and titling them Brattata and Okay Hot-Shot Okay! The paintings made Lichtenstein millions of dollars and hung in some of the nation’s most prominent modern-art museums. Heath said he was invited to an exhibition opening but couldn’t make it because he was busy laboring to meet deadlines.

Heath’s stories, like virtually all war comics of the time, remained locked in the patriotic lore of WWII. But the less conclusive outcome of the Korean War and the brutal televised spectacle of modern warfare in Vietnam had eroded the public’s taste for military adventure by the late 1960s. Despite his affinity for depicting the genre, Heath was no hawk. Interviewed by Dave Sim at the 1973 Detroit Triple Fan Fair, Heath said, “I think long ago men should have sat down and decided war is caveman stuff and is not a way of settling anything. A lot of wars, with political reasons in the background, are fought over territory, like in Vietnam, where most of the war was fought over the delta, which feeds a huge number of Asians. I think we’ve got to start thinking about getting rid of borders.”

If, for much of his career, Heath found himself recreating the Second World War over and over, it wasn’t so much because military conflict was his cup of tea, but because his style grew more out of the tradition of illustrating than that of cartooning. The war-comics genre was rooted in realistic details that were unnecessary in the world of Superman. Heath was able to capture those details so well that his comics actually undermined the glamour of war. In an essay written for the 1973 New York Comic Art Convention booklet, editor-writer Archie Goodwin wrote, “You believe Rock and Easy Company’s nightmare moments of battle. And believing those, you also believe the quiet and reflective ones when the madness of war is questioned or commented on. Russ Heath’s artwork has made it too damn real not to.”

Though never lacking illustrative detail, Heath’s art had an economy of line more common in European comics than in U.S. pages. That clean look may account for a parallel trajectory in Heath’s career: satirical cartooning. After doing several stories in 1954 for Atlas's Mad knock-off titles Crazy and Riot, Heath went on to hold his own in the real thing, drawing and inking the classic “Plastic Sam!” for Kurtzman’s Mad (#14, 1954). A funny, cartoonish parody of superheroes, it was everything his war comics were not. Heath also contributed to Mad #27 and #28, Kurtzman’s final issue. Kurtzman left Mad to create and edit Trump, a slick humor magazine for Playboy publisher Hugh Hefner, but he continued to seek Heath out, inviting him to contribute to Trump, as well as his subsequent humor magazines Humbug and Help. In an as-yet-unpublished conversation with TCJ publisher Gary Groth, Heath said, “I met [Kurtzman] when he was doing the Hey Look! strip for Stan Lee up in the Empire State building and we became friends and went out for lunch. And then he started feeding me little things at lunches … If I’d asked him to go to lunch more … I finally realized: I’m getting a job every time we go to lunch.”

Heath’s periodic collaboration with Kurtzman culminated in a hedonistic gig at the Playboy mansion as part of the art team Kurtzman hand-picked to produce his Little Annie Fanny strip. Heath worked on 15 episodes between 1963 and 1967. Several artists pitched in to draw the strip, including Arnold Roth, Jack Davis, Frank Frazetta, and Al Jaffee, but only Kurtzman and Will Elder worked on more episodes than Heath. All the artists filled in different bits of the strip at different times, making it difficult to tell who did what, but even working in this exaggerated cartooning mode, Heath’s more realistic tendencies crept in. Comparing his work to Elder’s, Heath told Groth, “My Annie Fannys have a little more bones in her body than his: his were very soft, unrealistically soft.”

To catch up with deadlines, a studio was set up in Hefner’s famous mansion in Chicago, and Heath was flown in to work with Kurtzman and Elder. As recounted at a 2010 L.A. Comic Art Professional Society dinner where Heath was guest of honor (and reported by Mark Evanier on his newsfromme.com site), once work on the strip was up to date, “Kurtzman and Elder left … but Heath just stayed. And stayed. And stayed some more. He had a free room as well as free meals whenever he wanted them from Hef's 24-hour kitchen. He also had access to whatever young ladies were lounging about … so he thought, ‘Why leave?’ He decided to live there until someone told him to get out … and for months, no one did.”

Eventually, Heath got an apartment nearby, but as he told Groth, he was “in and out of the mansion all the time.” Asked about life at the mansion, Heath told Groth, “I’m not going to say anything except I’ve had more than my share.” At the time, Heath was recently divorced from the high-school sweetheart he had married at the end of the 1940s.

The slogan “Make Love Not War” was first popularized in 1965, a year in which the phrase reflected Heath’s attitude and circumstances, but his playmate-filled idyll was short-lived. In 1966, he did a six-page war story for Warren’s Blazing Combat #4 (“Give and Take”) that he considered the best work of his career. It was his only work for Blazing Combat, which was soon canceled, but in 1967, he left Little Annie Fanny in order to devote himself more fully to the steady flow of DC war titles.

Heath drew a handful of color stories for Seaboard’s Planet of Vampires and Thrilling Adventure Stories in 1975, but in the late 1970s, Heath’s work often appeared in black and white: Although Blazing Combat was gone, he worked on Warren’s Creepy, Eerie, and Vampirella. He also returned to Marvel to draw some Kazar stories for the black-and-white Savage Tales.

In 1978, he moved to California, becoming a layout artist for the 1979 Godzilla animated series. This was followed in 1980 by animation layout work for The Tarzan/Lone Ranger/Zorro Adventure Hour, which put Heath in position to benefit from the push then being given the Lone Ranger by Hollywood. In anticipation of a 1981 Lone Ranger movie, the New York Times Syndicate launched a Lone Ranger newspaper strip written by Cary Bates and drawn by Heath. It was an opportunity for Heath to work on the kind of adventure strip he had grown up with, but the movie, starring a dubbed Klinton Silsbury, was a flop (it swept the Golden Raspberries that year), and the strip ran in only a few papers from 1981 to 1984. Heath’s art made it a handsome-looking strip, but the character had little to offer 1980s audiences. Heath had ghosted for Dan Barry on Flash Gordon in the 1950s and had assisted George Wunder on Terry and the Pirates and Stan Lynde on Latigo in the 1960s, but The Lone Ranger was his only stint as lead credited artist on a newspaper strip.

Heath continued to do animation work through the 1980s, mostly notably on the G.I. Joe series. He also supervised character design for the animated Karate Kid series in 1989.

After a decade of mostly animation work, Heath returned to comic books, again picking up assignments from Marvel, DC, or wherever he could get them. He was willing to work on costumed heroes who were able to operate without superpowers — masked vigilantes like Moon Knight (1989), the Punisher (1989), and Batman (Legends of the Dark Knight, 1993). During the 1990s, his art also appeared in DC’s Big Books anthology series, Marvel’s The Nam (1992), Dark Horse’s Bettie Page Comics (1996), and Penthouse Comix (1995). He did the comics adaptation of the Rocketeer movie in 1991 and worked on the subsequent Rocketeer series in 1992, apparently finding the character’s retro technology an acceptable form of superheroics.

Explaining where he drew the line (so to speak) with superheroes, Heath told Jones, “I am very literal. If Superman jumped over a building and hit the pavement, the pavement would shatter and the feet in Superman’s costume would be gone. … I have to believe it can happen or I won’t draw it.”

As the 21st century began, Heath was well into his 70s, still playing tennis, still going for six-mile runs and still drawing, but he was no superhero. His age began to catch up to him in the form of deteriorating knee cartilage. Like most aging, freelance comics artists, he couldn’t afford to stop working to have surgery done. Work had mostly become commissioned pieces, as well as odd art jobs here and there — DC’s Suicide Squad in 2002, Jonah Hex in 2008 — and a brief run on Legend for WildStorm in 2005.

In 2010, Heath received financial assistance from the Hero Initiative (formerly A Connection to Our Roots), as well as the Comic Art Professional Society, which allowed him to take time off for knee surgery and recovery. The Hero Initiative, a nonprofit source of financial and medical help for comics veterans in need, also provided legal and financial advice that aided Heath in claiming pension funds owed to him for his work in the animation industry. Heath had always been ambitious in both the quality and the quantity of his art in a way that had inspired his colleagues in the comics industry. At the end of his career, the industry paid its respects and granted him a long overdue rest.

Among his many honors, Heath received an Inkpot Award (1997), induction into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame (2009), the Comic Art Professional Society Sergio Award (2010) and the National Cartoonists Society Milton Caniff Award (2014).