“The only place where Negroes did not revolt is in the pages of capitalist historians.”

-C. L. R. James, “Revolution and the Negro,” New International (Dec. 1939).

* * *

C. L. R. James, the Trinidadian Pan-Africanist and revolutionary Marxist, wrote on a dazzling array of subjects that fit with his wide variety of interests. He wrote a history of cricket (Beyond a Boundary), an analysis of the works of Herman Melville (Mariners, Renegades and Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In) and a West Indian-set novel that was the first book by a Black Caribbean author published in the UK (Minty Alley). He is best known for his groundbreaking history of the Haitian Revolution, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, first published in 1938 and reprinted numerous times since. James drew inspiration from his own frustration. Years later, he said books about the Haitian Revolution at that time were “always talking about the West Indians as backward, as slaves, and continually oppressed and exploited by British domination and so forth.”1

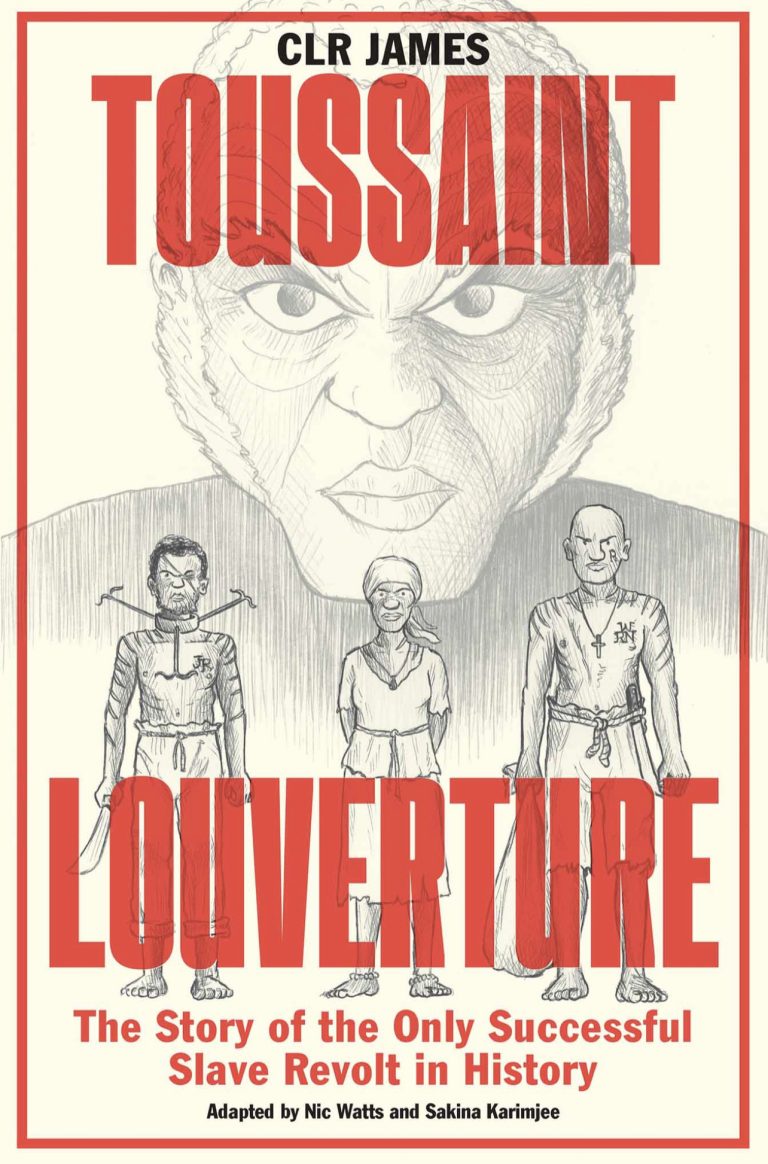

Before Black Jacobins, however, James dramatized the Haitian Revolution in the three-act play Toussaint Louverture: The Story of the Only Successful Slave Revolt in History. The play, first staged in 1936 and presumed lost until 2005, starred singer, actor and future blacklistee Paul Robeson as Louverture and was the first play written by a Black person starring Black people to be performed on the British stage. It is from this blueprint that Sakina Karimjee and Nic Watts have constructed a comic of the same title.

James would doubtlessly approve of his work being adapted into the comics form. While Marxists from publications like the Daily Worker and the Militant slammed comics—with the latter running a review of Seduction of the Innocent with the title “Comic Books -- McCarthyism For the Children”—James defended the art form. In his 1950 book American Civilization, he supported the study of comic strips Dick Tracy and Gasoline Alley and attacked the elitism of Marxist critics of popular culture: “to believe that the great masses of the people are merely passive recipients of what the purveyors of popular art give to them is in reality to see people as dumb slaves.” This is actually the second comic connected to James, the first being Milton Knight's The Young C. L. R. James (PM Press, 2018), which depicts scenes from Toussaint Loverture as well, albeit in condensed form.

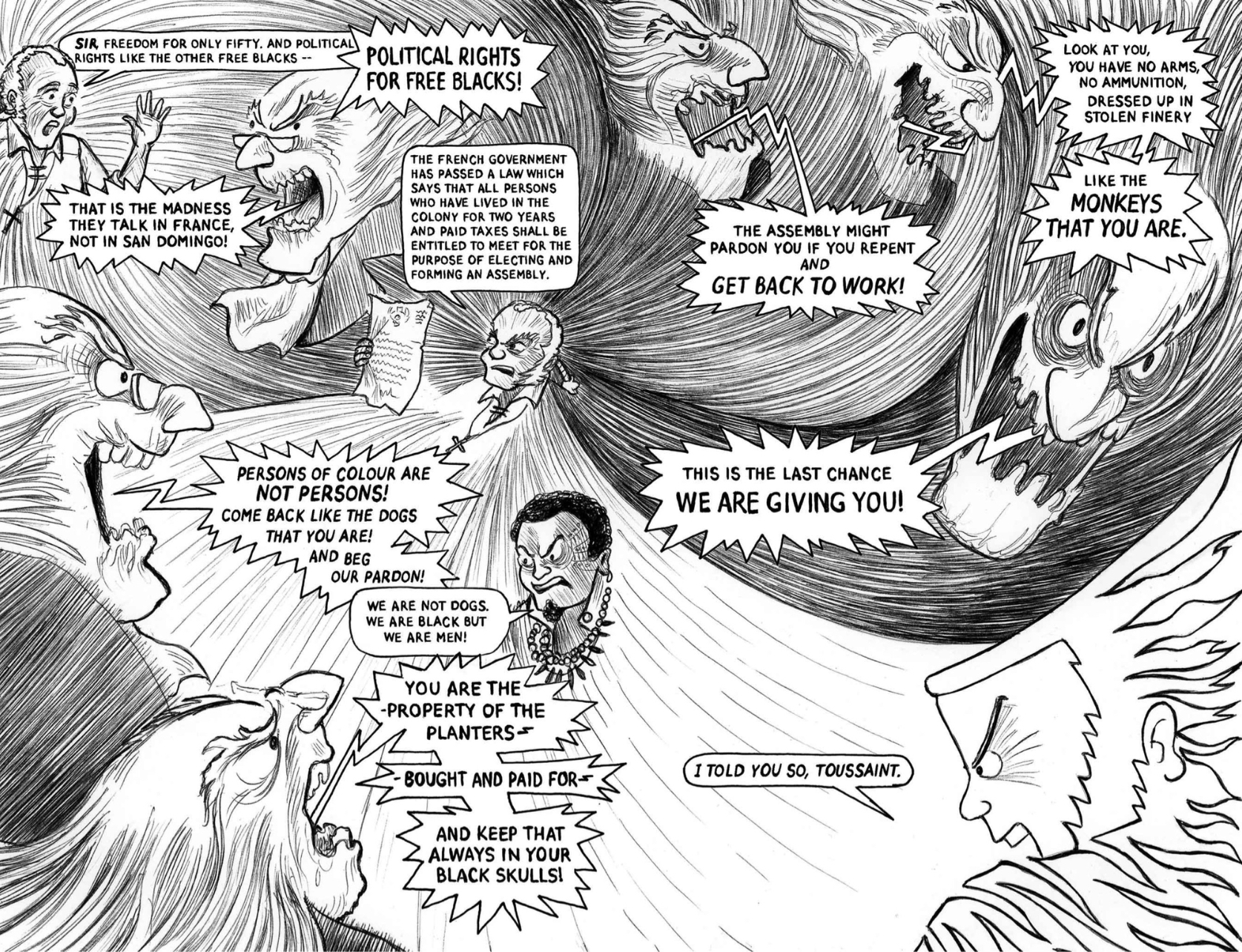

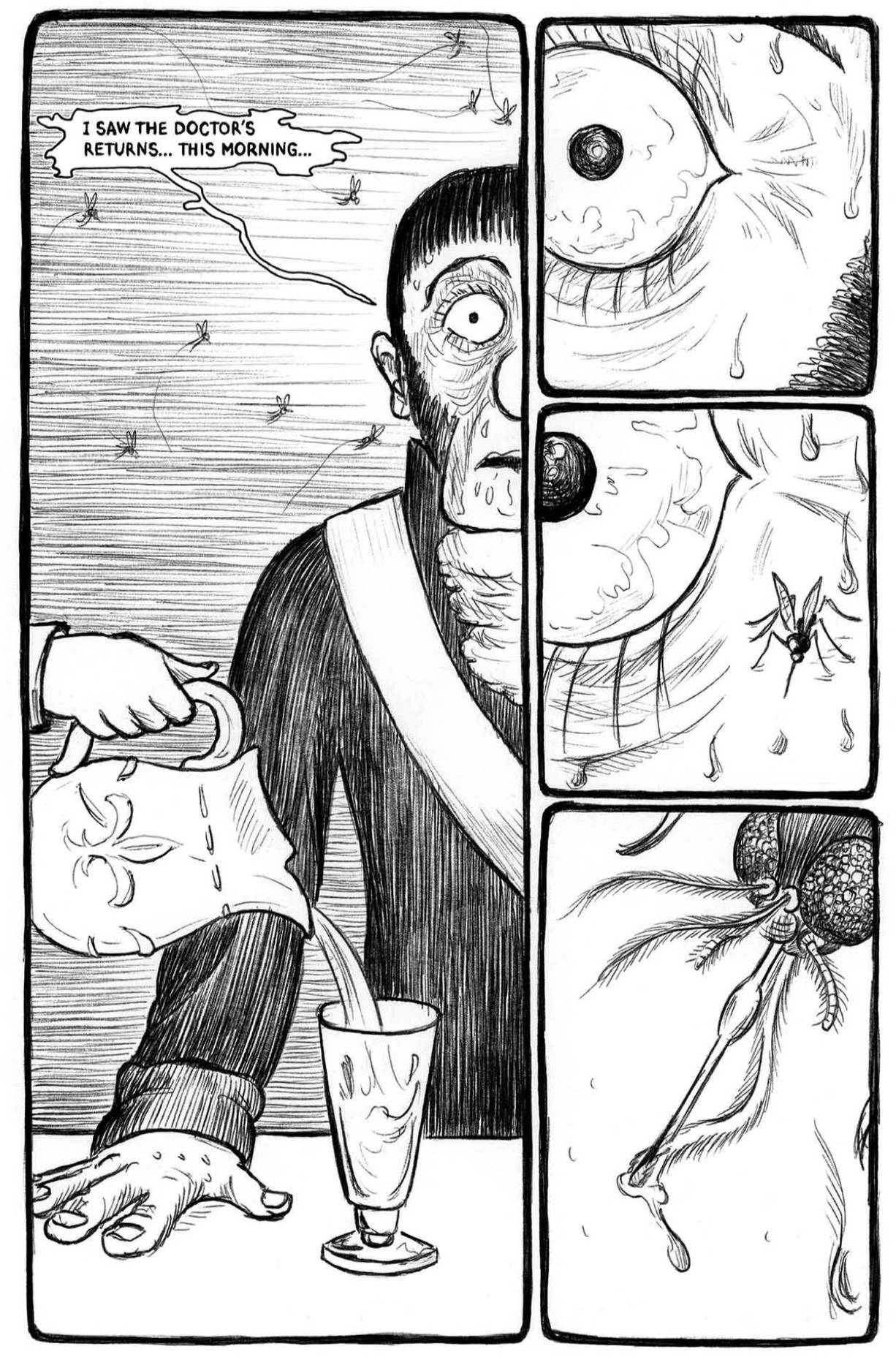

The artwork and compositions of Karimjee and Watts (per interviews, the latter is responsible for the finished art) lack the “staginess” that one would expect from a work based on a work of theater. James biographer Paul Buhle described the play as having “suffered badly... from overburdening dialogue.”2 Scott McLemee found it “a fairly ‘talky’ drama” as well, “worked up, rather too directly, from [James'] research into the Haitian slave revolt.”3 While some sections of the comic do rely heavily on dialogue, all of it taken from James' original, the authors take advantage of the medium by matching words with interesting images. A standout is a monologue from Bullet, the colonial administrator. Bullet is a vicious racist, and during one venomous monologue his face transforms into that of a skeletal monster as if from an EC horror comic. Graham Ingels would be proud.

The caricaturing at work in Toussaint Louverture is impressive. Each character has a distinct, stylized, expressive face. If somehow a reader forgets who is who, they can refer to an illustrated dramatis personae, but I only referred back to this page once, so identifiable are each of the designs. White characters are constantly depicted as sweating and surrounded by mosquitoes. The motif of sweat serves a dual purpose; it shows how out of their element these Europeans are in the tropical environment of Haiti, and highlights their guilty nature in attempting to deceive the revolutionaries.

In an interview with a socialist publication, Karimjee and Watts considered their work to be an educational tool. Karimjee: “A big part of our motivation is that this is a secret history. Outside of sections of the left so many people have never heard of Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution.” Watts: “The Haitian revolution is well represented in academic writing to a certain extent, but there’s virtually nothing on it in popular culture.” While these comments refer to a European context, it could be just as true for Americans. Most in the U.S. probably don’t know that Haiti was the first country in our hemisphere to abolish slavery; that President Jefferson promised to starve out the Haitian revolutionaries; that the U.S. military occupied Haiti from 1915-1934; that during this occupation forced labor was reintroduced. If the politicians who fulminate and filibuster about “critical race theory” and banning Maus and Gender Queer have their way, Americans will never be taught such uncomfortable truths.

Those leaders who are currently attempting to mandate teaching the beneficial side of the slave trade will doubtlessly fail to see the value of this work. Around a million slaves died due to the conditions of slavery in Haiti. The death rates of Black slaves on sugar plantations in Haiti were higher than those for slaves anywhere else. Karimjee and Watts mostly let the illustrations show the brutal treatment slaves faced. Their characters bear scars from whips, and some have had limbs amputated as a form of punishment. Another punishment, which we are told of, but do not see, involves a slave being forced to bury himself up to his neck. His face is smeared with honey and molasses, attracting ants, flies and other biting insects. If the master felt merciful he would allow the other slaves to pelt him with stones and rocks to put the slave out of his misery.

One educational aspect at which this comic falls short is its lack of contextualizing James’ script in the time it was written. There’s no text foreword or afterword in the comic, and no such information is conveyed in the comic itself. In fact, Toussaint Louverture premiered during the invasion of Ethiopia by fascist Italy. There was a growing Pan-Africanist movement against fascist tyranny, of which James was a leader in. He was a premier member of International African Friends of Ethiopia and the International African Service Bureau. This was the environment that Toussaint Louverture was born into. Hopefully, readers will take advantage of the suggestions in the Further Reading section to learn more.

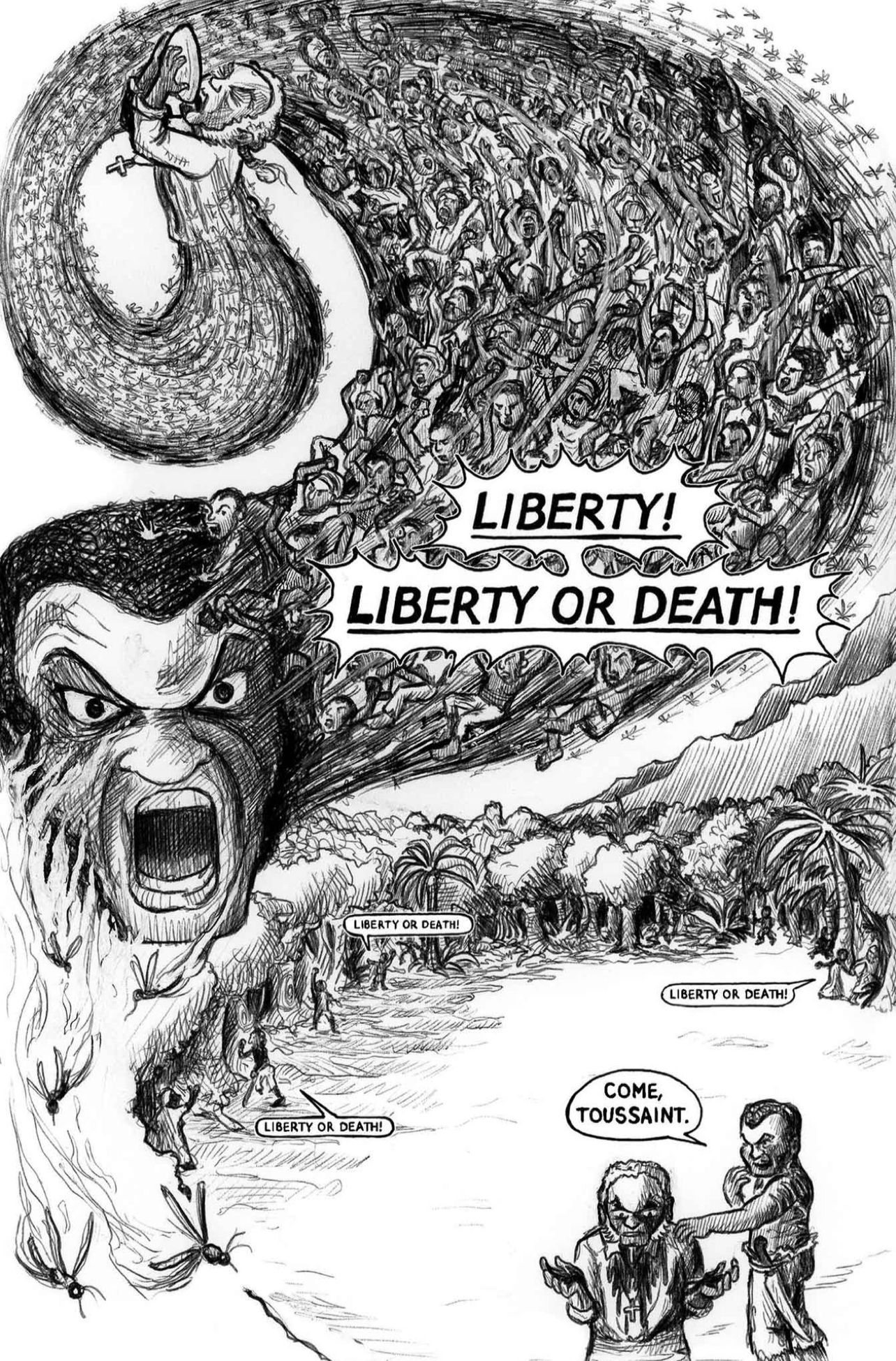

While the aim of this volume is educational, entertainment is not forgotten. The Haitian Revolution featured fierce battles, diplomatic treachery by the European powers, and human drama on a grand scale. We see the rise and fall of Louverture, from his beginnings as a slave on the periphery of the revolution, to his development as a trusted leader of the revolt, to his final betrayal by the Napoleonic French. But James does not subscribe to the “great man” theory of history, and it is clear that without the support of the masses of former slaves that Louverture could not have achieved all that he did.

There have been very few English language dramatizations of the Haitian Revolution. Toussaint’s life was going to be subject of a film directed by Danny Glover, but the project never happened. Until such a piece as that materializes, this comic will do as a dramatization of this historical event. Writing in The Black Jacobins, James proclaimed “The transformation of slaves, trembling in hundreds before a single white man, into a people able to… defeat the most powerful European nations of their day, is one of the great epics of revolutionary struggle.”4 It has also become a great epic in comics.

* * *

- MARHO eds., Visions of History (New York: Pantheon Books, 1983) 267.

- Paul Buhle, C. L. R. James: The Artist as Revolutionary (London: Verso, 2017) 56.

- Scott McLemee, “American Civilization and World Revolution: C. L. R. James in the United States, 1938-1953 and Beyond,” C. L. R. James and Revolutionary Marxism: Selected Writings of C. L. R. James 1939-1949 (Chicago: Haymarket, 2017) 112.

- C. L. R. James, The Black Jacobins (New York: Vintage Books, 2023) ix.