Tracy Auch’s necrophilic landscape is a combat zone, the site of a schism between adults and children. The story’s kids, dissidents behind “the blight of child crime,” have started using vessels in the shape of adult bodies to infiltrate the adult world. Lucas Barrette, an ace detective, responds in kind; he opts to be divided at the waist before he enters a child stronghold. Barrette’s body is split into autonomous halves and placed atop pairs of prosthetic legs, so that he better resembles (twice over) the vessels of the child criminal element. Barrette’s head tops one of the new entities, and his genitals top the other. This marks the end of the comic’s prologue; it’s a memorable start to a demanding, singular story.

Tracy Auch has created work under a few different names (e.g. her contribution, as “Hennessy,” to Austin English’s Tusen Hjärtan Stark #2), though The Necrophilic Landscape may be her most visible piece of cartooning, given the growing profile of its publisher, 2dcloud. Even so, a couple of years removed from the comic’s release, there’s not much writing on Landscape, which could be a function of Auch’s opting out of typical brand-building or of Landscape as a challenging work.

Both Auch’s layouts and the contents of her panels create a sense of anxiety throughout The Necrophilic Landscape. On most pages, the panels nearest each other share borders (instead of a gutter lying between them), and the effect is a squeezing out of readerly breathing room. Separating the foregrounds and backgrounds of Auch’s pages sometimes requires an atypical amount of readerly work as well. In the comic’s opening scene (wherein the detective cuts off a baby's head and puts it on his own in order to walk among other children) and a later scene in which Barrette is trapped inside a church of the child realm, Auch depicts the wood grain on floors and ceilings with such a volume of strokes that the pages appear to shout. The effect is almost as much aural as textural. In other areas, narration or dialogue occupies about half of each panel, another overwhelming effect.

Both Auch’s layouts and the contents of her panels create a sense of anxiety throughout The Necrophilic Landscape. On most pages, the panels nearest each other share borders (instead of a gutter lying between them), and the effect is a squeezing out of readerly breathing room. Separating the foregrounds and backgrounds of Auch’s pages sometimes requires an atypical amount of readerly work as well. In the comic’s opening scene (wherein the detective cuts off a baby's head and puts it on his own in order to walk among other children) and a later scene in which Barrette is trapped inside a church of the child realm, Auch depicts the wood grain on floors and ceilings with such a volume of strokes that the pages appear to shout. The effect is almost as much aural as textural. In other areas, narration or dialogue occupies about half of each panel, another overwhelming effect.

Auch’s work might be grouped first with that of English or Andrew Burkholder, but certain elements in The Necrophilic Landscape recall much older creations. By the broadest definitions of expressionism—art emphasizing subjectivity in its depiction of the world, art using visual distortions to evoke emotion—a lot of comics are expressionist, but Auch's comic occasionally brings to mind capital-E works, the stuff of Munch and Murnau. When Barrette is in his office, settling on his disguise(s), Auch’s approach to shadow further heightens the story’s reality, with a series of thick, triangular spot blacks shifting across the top of the page. Later, in a scene depicting an organ theft, two figures’ shadows merge to create a batlike mass on a nearby wall, amplifying the menace of the moment.

Despite being, unrelentingly, an art comic, The Necrophilic Landscape isn’t shy about utilizing genre conventions. Pulpy, ironic narration describes the detective’s quest, the sort that would not have been on a ’40s radio serial: “No one would expect that these two figures are in fact a single man: the fearless detective Lucas Barrette.” (The detective, for his part, bears a sideways resemblance to McGruff the Crime Dog.) The children’s means of infiltrating the adult world echoes the comedy trope of two kids walking one atop the other in a single large coat. And the story’s dystopian trappings provide a context for Barrette’s fantastical procedure. But the most compelling generic element is one the story shares with horror: the protagonist, Barrette, stands for order and orthodoxy, with the story’s antagonists, the children, deviating from that orthodoxy—and readers are likely to empathize with the antagonists to a degree that the protagonist does not. (By the end of the comic, Barrett hasn’t assumed the role of villain, but he doesn't have much of a defense to offer on behalf of the prevailing order.)

The slipperiness of the characters roles suits the slipperiness of The Necrophilic Landscape as an allegory. On the book’s back cover, the reader finds a passage from feminist theorist Mary Daly, the sort of thing that colors the comic’s range of interpretations:

Males do indeed deeply identify with “unwanted fetal tissue,” for they sense as their own condition the role of controller, possessor, inhabitor of women. Draining female energy, they feel fetal. Since this perpetual fetal state is fatal to the Self of the eternal mother (Hostess), males fear women’s recognition of this real condition, which would render them infinitely “unwanted.” For this attraction/need of males for female energy, seen for what it is, is necrophilia—not in the sense of love for actual corpses, but of love for those victimized into a state of living death.

The world of Auch’s story appears to be dominated by cisgender men and boys, and so it’s possible to read the comic as a story of masculinity tearing itself apart, something like the superego of Detective Barrett versus the id of the child criminals. But any allegory here is, again, a slippery thing. The comic’s children also inhabit the role of marginalized figures—they revolt against prevailing notions of wholeness, telling Barrett that, “in this world you have created, children are those who count for only half a creature—who are forced to subordinate themselves as only half a living body.” The Daly quote, rather than settling readers’ impressions of the story, may urge them right back to it, and toward further tensions, further confusion. (Or, of course, readers may opt to ignore the quote’s apparent binary thinking.)

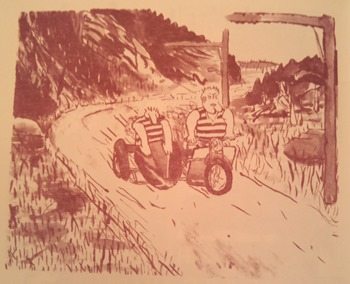

In a dovetailing of story and circumstance, The Necrophilic Landscape is technically an unfinished work, published after its initial abandonment, and it reads, on multiple levels, like the start of an interrogation. Auch’s sense of humor resonates strongly—certain images, like Barrette-from-the-waist-up driving a motorcycle while Barrette-from-the-waist-down rides in a sidecar, are likely to stick in readers’ minds. But so does the anxiety of the story, which occupies even panels focused on comedic beats and genre riffs. And taken together, they form a bracing work, compelling both in spite of and because of its incompleteness.

In a dovetailing of story and circumstance, The Necrophilic Landscape is technically an unfinished work, published after its initial abandonment, and it reads, on multiple levels, like the start of an interrogation. Auch’s sense of humor resonates strongly—certain images, like Barrette-from-the-waist-up driving a motorcycle while Barrette-from-the-waist-down rides in a sidecar, are likely to stick in readers’ minds. But so does the anxiety of the story, which occupies even panels focused on comedic beats and genre riffs. And taken together, they form a bracing work, compelling both in spite of and because of its incompleteness.