As in her previous release with Drawn & Quarterly, The Waiting (2021), Keum Suk Gendry-Kim’s The Naked Tree continues her exploration of the immediate and long-term effects of the Korean War. Unlike that book, though, Gendry-Kim’s newest is an adaptation of another author’s fictional work. The Naked Tree was originally a 1970 novel by Park Wan-suh, her first, which she published when she was 40 years old. Rather than simply shifting that novel to a graphic format, Gendry-Kim makes changes to tell the story she wishes to tell. Ho Won-sook, Park Wan-suh’s daughter, in fact, comments in the introduction, “…after rereading [Gendry-Kim’s adaptation] several times, I noticed it had a kind of charm different from that of the original. It was as though the artist had burrowed into my mother’s soul to bring out the intentions of the original story, while fleshing out the characters and scenes in a fresh, imaginative way, breathing new life and humor into the work.” In Gendry-Kim’s adaptation, Park Wan-suh’s motivation for telling the story now frames the main narrative, with the author herself as one of the characters, helping to highlight one of her significant themes: what it means to be an artist, especially in the midst of a war.

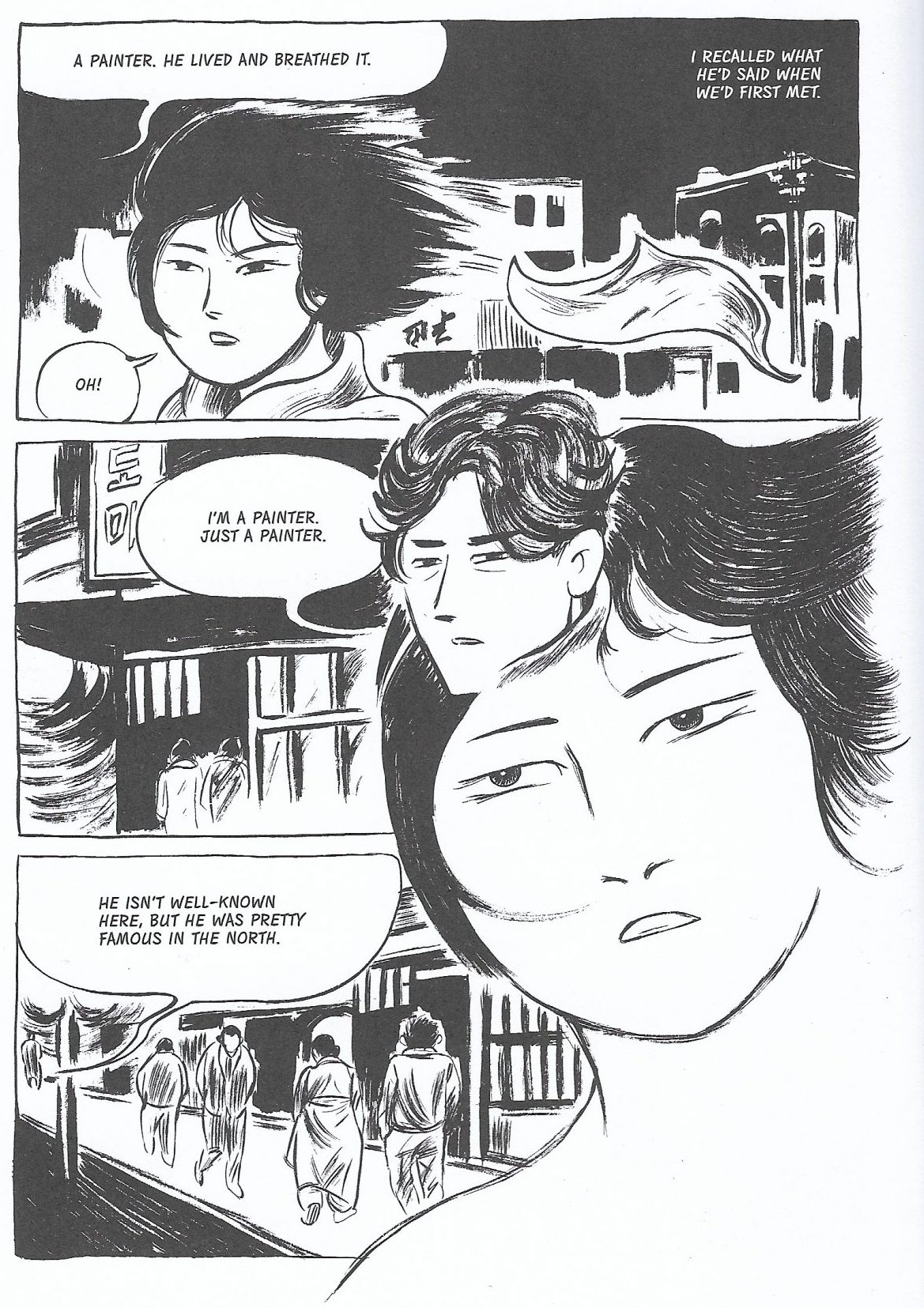

The primary narrative begins in 1951, during the Korean War. The main character, Miss Lee, works at the Post Exchange (PX), a retailer that sells duty-free goods to American soldiers. Her job is to entice the soldiers to buy 'silk' scarves for their girlfriends, wives or lovers; there are two artists who work with Miss Lee, who then paint those women's portraits on the scarves. Miss Lee lives with her mother, who doesn’t seem interested in her daughter or in their relationship; she barely eats, and seems to be waiting to die. Miss Lee’s boss ends up hiring a new painter, Ok Huido, who doesn’t say much and focuses on the work at hand. When the other two artists ask him if he’s done such work before, he says that he hasn’t, that he’s just a painter, leading them to guess that he works painting billboards.

It becomes clear quite quickly that Miss Lee is attracted to Ok Huido, even though he’s married. She goes on walks with him after work, always meeting up at a turn-key chimpanzee that bangs cymbals together. When Ok Huido has missed a few days of work, Taesu, one of his friends and an admirer of Miss Lee, takes her to Ok Huido’s house. Even though Miss Lee can see the affection between Ok Huido and his wife, her attraction only deepens. After one of the most difficult nights of her life, she ends up at their house, though he is out. His wife shows Miss Lee his paintings, and she realizes Ok Huido is much more than a billboard painter; he’s an artist of higher ambition.

The book's title manifests as a naked tree, one without leaves, that grows between Miss Lee and Ok Huido when he takes time off work to explore his art, to find out if he really is an artist, as he believes. He tells her, “I’m more afraid to find out I’m not an artist than to die. If I’m not an artist, I’m nothing. I’d rather die if I can’t make real art.” They are talking beside a naked tree, which slowly moves between the two of them as they have this conversation. Gendry-Kim has the tree become the center of a borderless image so that it completely separates the two characters from one another. The two-page spread is stark, as the black tree sits against a white background, with the two characters the only other subjects of the page. The following pages show them moving in separate directions, still divided by the tree.

The final chapter, also titled “The Naked Tree,” returns to the frame tale where Gendry-Kim’s work began. Park Wan-suh, in 1969, is attending a posthumous exhibition of artwork by Park Su-geun, an artist she knew in her youth who will soon prompt her to write the 1970 novel. It’s after viewing this exhibit that Park Wan-suh ascertains from one of his paintings the naked tree as a metaphor for Park Su-geun. She overhears numerous people at the exhibit talking about all that he struggled with during and after the war, while he was still trying to create art, and she concludes, “A naked tree trembles in the winter wind, having shed its last leaf. It yearns for spring. Still it stands firm, persevering in the cold, because it knows that spring is coming. I know now that Ok Huido was the naked tree. He’d persevered like the tree during those dark days, when his life was hard.” Even though he received little recognition during his life, Ok Huido (and, thus, Park Su-geun) believed he was an artist and produced his work because it was what he felt called to do.

Miss Lee’s life also has challenges that stem from her family dynamics. Her father abandoned the family years ago, leaving her mother to raise her and her two brothers. The reader doesn’t discover the reality behind the family tensions until much later, helping them to understand the complex relationship between Miss Lee and her mother. As with so much in the book, her complicated family life stems from the war. Miss Lee even uses the wind-up chimpanzee as a metaphor for the effect the war has on her and Ok Huido’s lives: “How were we any different from this chimp? Wasn’t the war controlling our lives, like the key on the back of a wind-up toy? Just as I couldn’t free Ok Huido, he couldn’t help me at all.” Though Miss Lee has the freedom to leave her mother and move to safety, she feels bound to stay. She feels as if she has no choice in her life.

The frame tale drives that idea home, developing the question of what one will sacrifice for art and whether that sacrifice is worth it - some of the decisions Park Wan-suh has made are called into doubt. The war had its effect on her as well, leading to existential questions of her own. The Naked Tree leaves the reader with these questions, while exploring the effects of a war so many seem willing to forget.