Reading Geneviève Castrée's childhood memoir is not unlike watching someone pull at every one of their old scabs and scars, leaving themselves bleeding and torn. And I do mean every one, as Castrée chronologically documents every hurt, every slight, every refusal of affection, and every thoughtless maternal dismissal. A child tends to crave routine, affection, agency, and a certain solidity from her parents. From her single mother, Castrée apparently received a life of constantly shifting emotional quicksand. The relationship between the two, especially as Castrée grows older, is less mother/daughter than big sister/little sister. Only the big sister is in charge of her younger sibling and authority has gone to her head, as she uses her position to severely punish her younger sister for any personal slight. Castrée is never given any choices or agency, no matter how small.

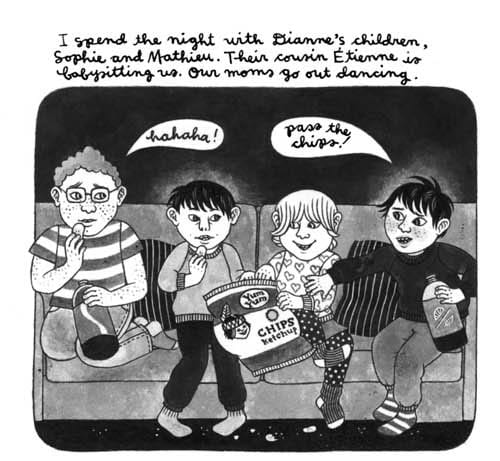

The book is divided into roughly two sections: pre- and post-adolescence. Pre-adolescent "Goglu" (Castrée's stand-in character) is constantly confused and bewildered, desperately wanting to feel safe and secure. Instead, she gets a constant diet of her young mother acting like the immature partier that she is. We get scene after scene of her mother and her friends drunk, high, causing accidents, and getting into loud, upsetting arguments--all with Goglu present to watch them. The most malevolent member of the cast of characters is Omer, her mother's icy live-in boyfriend. There's almost a relish with which Castrée draws him--all sneers and furrowed eyebrows, as though he long ago crushed any compassion or gentleness he might have held in his expression. The first half of the book consists of Goglu trying to make sense of her world and come to terms with her absent father, who lives at the other end of Canada, and whom she does not see between the ages of five and fifteen. It climaxes in her overhearing her mother express regret at not getting an abortion, which of course manifests in guilt on Goglu's part, as she urges her mother to go back to school.

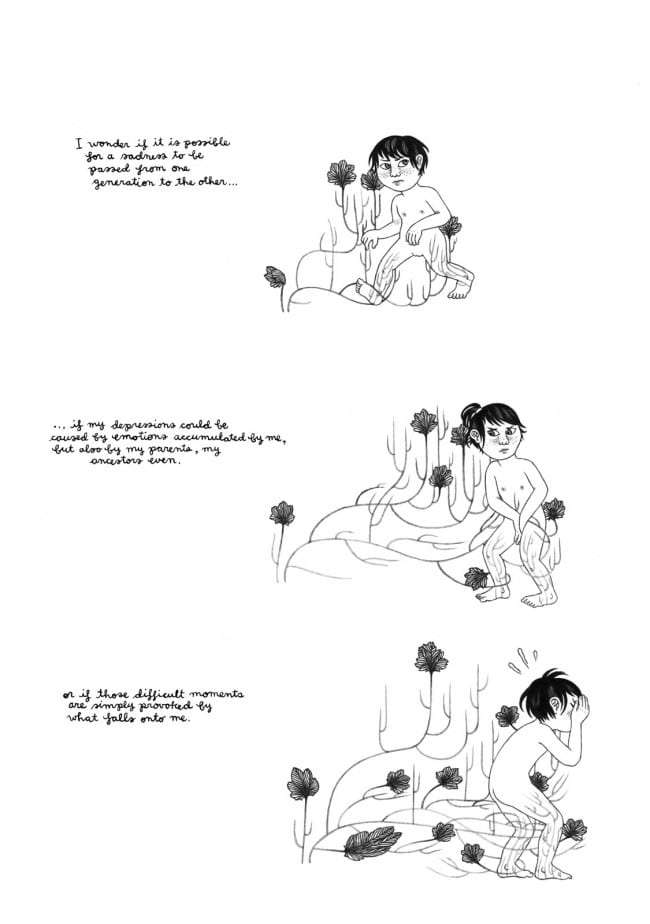

Of course, that would presume that her mother's emotional development didn't end at the age of seventeen (when she gave birth). As she gets older, her drunken and stoned antics start to deeply embarrass Goglu, whose house is inhospitable to having friends over. The older her mother gets, the more she seems to regress emotionally. It's not even a case of benign neglect, as Goglu is punished for arbitrary slights (like using Omer's stereo or spilling something). Goglu starts talking back to her mother, with the insult of "drunkard" earning not just a grounding, but the silent treatment. As bad as physical abuse is from a parent (and Castrée documents only one occasion of this), emotional abuse can be just as scarring, and being totally shut out is something that inspires despair from a child. It's also part of her feeling of total alienation that is heightened as a teenager. She's an outsider at school (as one incident involving a bloody tampon being flung into her mouth demonstrates) and is confronted by the guilt of her mother telling her she's responsible for her relationship with her boyfriend getting worse. Things come to a head when her mother doesn't believe Goglu is a virgin and slaps her as Omer encourages that bit of violence. The violence is almost less hurtful than the continual accusations throughout her life that she's a liar. That leads her to being seen by a doctor and nurse who take her seriously, who note that her anger is being turned back on herself. That's an important note to consider when reading the end of the book.

Goglu slowly, painfully makes friends in the punk scene and consoles herself by being creative. There is a heavy Julie Doucet influence at work here in more ways than one, but especially in terms of her figure drawing (while lacking Doucet's almost neurotic need to fill up every panel with details). Indeed, it's the negative space that most often brings home Goglu's sense of alienation, like one beautiful page with Goglu at its center, with some art supplies and paper slowly sprawling out from around her, with nothing else on the page. It's her only connection to the world in that moment. Doucet and other cartoonists had to have been big inspirations, with Doucet being a Canadian cartoonist who broke free of alienating and limiting relationships.

A visit to her father reveals a man who loves her but is every bit the fuck-up her mother is. In this case, however, he has a loving and supportive partner who keeps him centered, so the effect is more a case of benign neglect. He doesn't know how to help her, but he doesn't stand in her way, either. Things come full circle for Goglu when she becomes pregnant. Rather than being furious, her mother is supportive and helps her to get an abortion. Her mother wants to help her avoid her own fate, which may be the only really great thing she does for her as a parent. At the same time, when Omer tells them that he wants to leave because Goglu and her mother are too close "and there's no room for me," accepting no responsibility for his own actions, Goglu knows things are over. She's all set to move out but her mother refuses to co-sign on a lease, which leads her to go back to her father, who builds her a log cabin in the wilderness. That last bit was powerful both as a real-world event and as a metaphor: all he can do is give her a proper setting for her loneliness and alienation in hopes that she can come to terms with it.

Castrée does not defend her own actions as a teenager, nor does she have to. She was made to feel like a hopeless failure who can't do anything right and has a hard time getting away from internalizing that feeling. Guilt and shame are her default feelings. If the end of the book feels a little childish ("I can do whatever I want"), it's not because she's acting like a child who makes petulant demands. It's because she's finally an adult who understands that she possesses the agency she's craved all of her life, and that she doesn't have to stand for the emotional blackmail her mother tries to inflict on her ("Well, you've abandoned me..."). Susceptible seems to be the final, necessary externalization of the anger and confusion that Castrée turned inward all her life. It's telling that it's been thirteen years since the events at the end of the book; that seems to be enough time to process memories while still feeling the emotions attached to those memories in the present tense. Castrée is clearly not ready to forgive, even if intellectually she understands the position her mother was put in. The result is a primal howl, perhaps less a compendium of wounds than an extended expulsion of built-up bile. I'll be curious to see how she deals with the subject of her childhood in later work, if she does indeed even choose to do so. Castrée has created something beautiful and ugly as a marker for a childhood of neglect, uncertainty, and alienation.