“Science fiction is not 'about the future.' Science fiction is in dialogue with the present... a significant distortion of the present that sets up a rich and complex dialogue with the reader's here and now.”

- Samuel R. Delany, Starboard Wine, 1984

Social Fiction collects a sequence of three dystopian graphic novellas which imagine totalitarian surveillance states structured around eugenics. Each story presents a different dystopia, often built around a feminist observation that wherever people are oppressed, reproductive norms are enforced by the ruling class. As the title suggests, Chantal Montellier's focus is on social life under dictatorship - marriage, divorce, torrid affairs, homosocial friendships, rivalries under the eye of the panopticon. Arguments, dreams, fantasies and aspirations still exist within the people living in Montellier's dystopias, and her stories explore how a rich inner life might be shaped by oppressive forces, in imaginary futures, in our own place and time.

Montellier envisions future societies where bodies are subject to intense scrutiny. In Wonder City, the government carefully selects desirable couples for pregnancy and quietly sterilizes the non-white population. The scenario presented unfolds at an Orwellian scale, aided by labyrinths of computerized technologies of surveillance and regulation, but closely parallels the eugenicist social engineering prevalent in the United States and Canada in the 19th and 20th century, ideas and practices which inspired Hitler’s Nazi party. Although a technologically advanced oligarchy, this future is very much a past and present reality, and Montellier trains her eye on its mundanities, the routine of blue collar labor, women’s work, clubbing, affairs. Every page is a cacophony of faces: passersby taking up the foreground of panels, disrupting the narrative scenes and begging the reader to imagine every unspoken life in the margins of this world (although some readers may wish to question Montellier’s relegation of impoverished Black people to anonymous, largely silent faces in the crowd, presented for shock value as her white working class heroine discovers the state has secretly begun their genocide).

Punks and rebels still exist in Wonder City, and unlike many dystopias escape is possible. But Montellier’s psychological bite troubles any message of hope; an incisive dip into the thoughts of her escapees reveals how their hopes remain shaped by societal norms of the totalitarian society they have fled, as drab in their logic as a social media algorithm. Montellier asks the reader to question their own rebel visions - how strange might our notion of a better world look divorced from the paradigms of today? Are our own ideas of liberation enough?

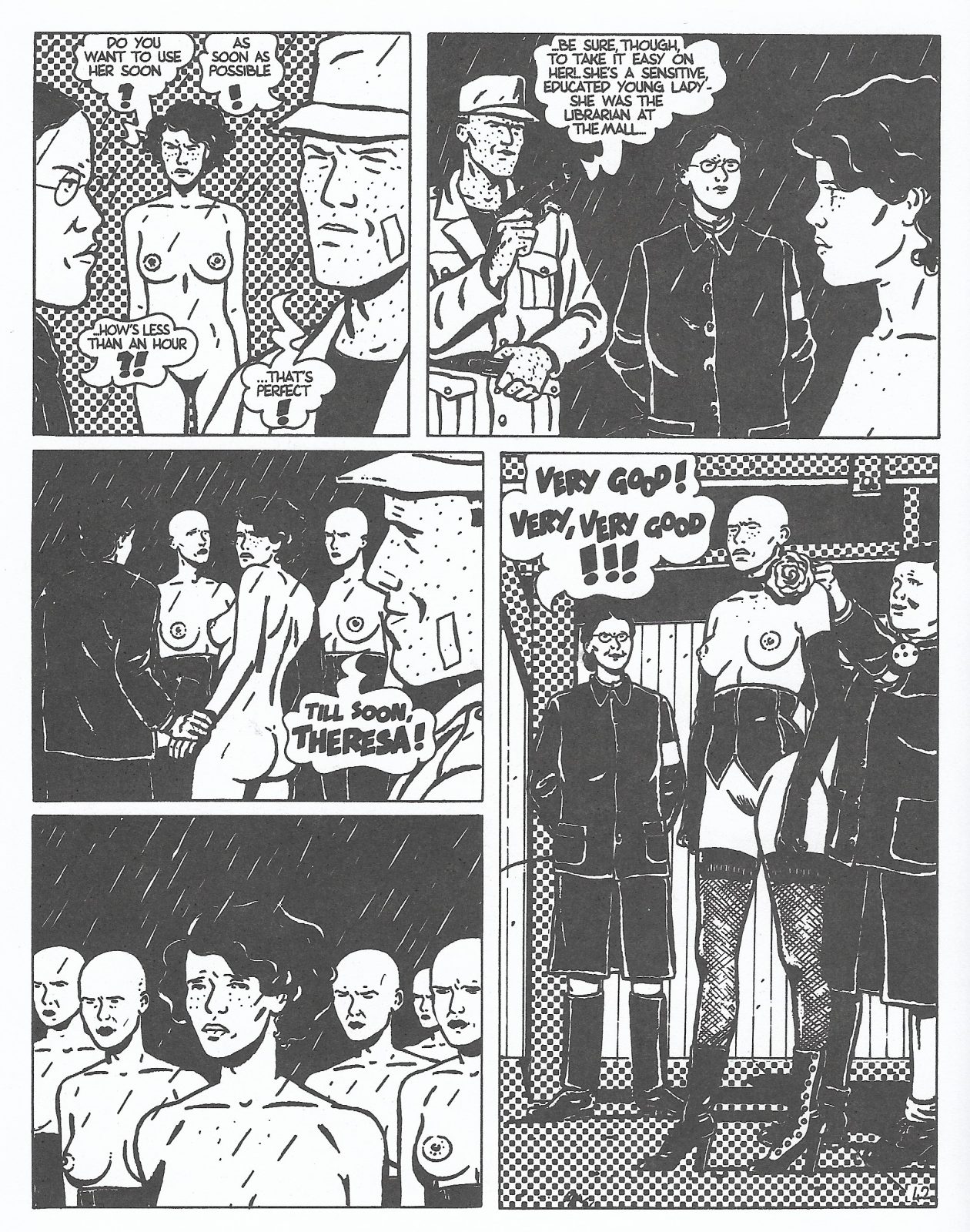

Sexual violence is a guiding principle of police states throughout Social Fiction. In both Wonder City and the earlier Shelter, rape is wielded by law enforcement as a weapon to silence women, while pregnancies and abortions alike are forced by agenda without even the thought of consent. These depictions are shocking, but nonetheless true to life - a woman’s attempt to report her rape at the hands of police officers in Shelter falls on deaf ears as the agency nominally meant to help her is the same as the one which assaulted her, their leers and dismissive comments while hearing her report even more disturbing than the actual scene of her violation. Sexual violence invades the parameters of women’s dreams; in both Wonder City and Shelter, women dream of their violent mistreatment by the state as a pornographic fantasy, their bodies naked and exposed yet powerfully erotic, marching to exotic versions of forced birth and encampment, respectively. Shelter in particular obscures the precise moment when the story slips into its protagonist’s dream, forcing the reader to confront the disturbing organizing force which the threat of rape plays in our society, whether it happens or is simply feared.

Irony is a constant in these stories, illuminating the contradictions of fascism. In Shelter, cops check out books on philosophy and political theory from the library so that they may be burned. The mall plays a similar role in Shelter as in Romero’s Dawn of the Dead: capitalism continuing to structure a nominally socialist society in the wake of nuclear armageddon. The mall is still a mall - its essence corrodes the titular shelter’s liberating potential into a police state by its very corporate structure. The final irony of Shelter only stands to affirm the powerlessness of consumerism. Elsewhere, in the yet-earlier "So Fast In Their Shiny Metal Cars" (the longest segment of Montellier's 1996), consumerism and fascism continue to mingle in a future America where racial segregation enters the market of death - corpses of car crash victims are kept in their vehicles while parts are stripped for sale, with white victims displayed embalmed on one floor while the bodies of colored victims are left to rot one floor below. However, a third strata of corpses exists: one of racially ambiguous and mixed bodies misidentified as white, a chilling revelation artfully illustrating the contradictions of white supremacist logic in the story’s closing pages.

If I were a worse critic, I would praise Social Fiction for its prescience. For any reader coming to this comic at this time, months into into a rash of climate-induced forest fires that have taught us to check the air quality like the weather while new legal restrictions on gender expression and sexual bodily autonomy roll in and out haphazardly like storm clouds, one can be forgiven for feeling on some gut level that this collection of graphic novellas saw into our own future. However, Montellier is no prophet, but rather a feminist and an anti-fascist. Her dystopias of the '70s and early '80s address political, social and technological conditions which follow from patriarchy. Her alternate futures are real because they flow from our present, and her insights remain relevant and profound.