A new manga by Hayao Miyazaki. You can tell this is a big deal by a simple fact of the cover design: the creator’s name is bigger and more prominent than the name of the creation. We are not quite at the Stephen King level, the people-are-gonna-buy-it-no-matter-what-title-we-use level, but we are getting close. Which, on the face of it, is weird. Miyazaki is first (and second and third) and foremost a movie director, an animator. His manga work, as far as the English-speaking world is concerned, is limited to Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1982-94),1 which is greatly admired… but not to the degree of its film adaptation.

And now we have this, Shuna’s Journey. I called it ‘new’ when the better terminology would be ‘new to us’. This short book, released by First Second 2 originally came out in 1983, while Miyazaki was still working on the Nausicaä manga. Up until the announcement of its publication I had hardly seen any discussion of it, certainly not as a lost masterpiece begging for translation. A friend, an academic scholar who has written extensively about Miyazaki, referred to it as a curio. A worthwhile curio, because Miyazaki is just that good, but only a footnote in the man’s oeuvre.

Here it is, printed nice - a small (6.25" x 8.75", not as small as the usual digest size) hardcover, translated by Alex Dudok de Wit. You can certainly see why some would take it as just a stepping-stone for larger things. Several of the story cues and many of the visual ideas would be reused later in Miyazaki's film work to greater acclaim. Both the appearance of the protagonist and his beast of burden will be instantly familiar to anyone who saw Princess Mononoke. Yet, I am forced to disagree with my academic friend; this isn’t a curio, this is a damn fine book on its own terms, worth a read whether you are familiar with the creator’s later works or not. It stands by itself.

Copyright © 1983 Studio Ghibli

All rights reserved.

First published in Japan by Tokuma Shoten Co., Ltd.

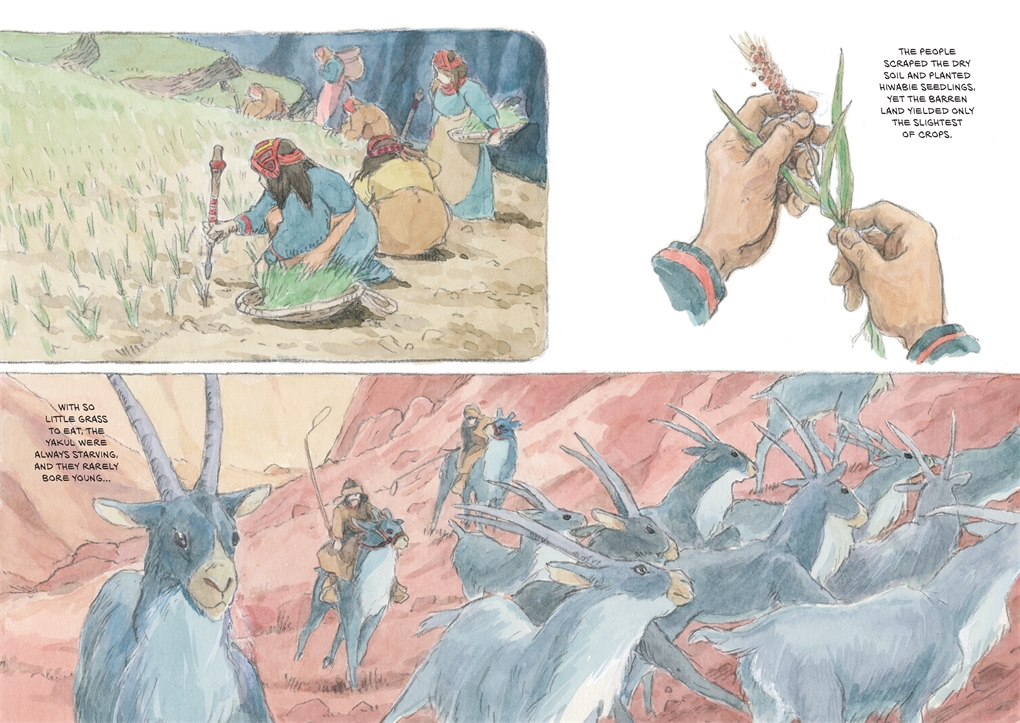

The basic story follows Prince Shuna, the future leader of a tribe living in an extremely harsh environment. They can just about grow enough food to live on, but nothing more. A chance encounter with a dying traveler reveals to Shuna the possible existence of miraculous ‘golden grain’ that can grow rich even in a soil as arid as Shuna’s kingdom. So, despite the begging of his people, Shuna takes a rifle, some supplies, and his Yakul (the above-mentioned beast of burden), and goes out on a long journey to find the golden grain. It’s a quest story - the untested youth goes outside the world he's known all his life and encounters new people and phenomena. You can be pretty sure that by the end of the book our protagonist would stop being a youth and learn to be a man. Familiar ground, though Miyazaki is said to have based it on a Tibetan folktale, “The Prince who Became a Dog”,

There’s certainly a more mythic flavor to this story than usual. Miyazaki's works usually deal with the fantastic, but often in a manner that feels more grounded than Shuna’s Journey. To bring back the Princess Mononoke comparison, the action of that film took place in a well-defined time and place, within a society that is clearly understood by the viewer as the story progressed. (Even if you don't know everything about that time and place, there's enough visual details to clue you in to how everything works.) This remains true even in Miyakazi's films that fabricate their setting out of whole cloth; there's always so much there, even if just in the background, to give a sense of a fully-functional world. Shuna’s Journey keeps things more obscure. We can never quite be sure where or when this story happens: it could be the past; it could be a Nausicaä-like post-apocalypse future; it could be another world; it could be Australia. We don’t know, because we don’t need to know.

Copyright © 1983 Studio Ghibli

All rights reserved.

First published in Japan by Tokuma Shoten Co., Ltd.

The art, full watercolors instead of the more traditional b&w pencil and ink, is a reflection of this mythic mode. For a creator known for his attention to detail—every bolt in every aircraft, every seam in every piece of cloth rendered as realistically as possible—this work has a more ‘washed’ look to it. The small size doesn’t mean details are lost, simply because there aren’t that many details. This is not to say Miyazaki compromises his harsh standards; you can see his carefully-planned construction in the design of the rifles in the caravans and devices used by the slave traders, but these appear only when he chooses. Mostly he draws less-defined spaces in this work.

The overall page design helps with this dimension: the highest number of panels per page is three, with many more going for just two panels, or even a full-page splash.3 There are no speech balloons or even caption boxes; both narration and dialogue are printed right atop the artwork, giving sections of the book a feeling more akin to illustrated novel than ‘comics’ - as if we are not reading the story in the present, but hearing an account from long ago.

Copyright © 1983 Studio Ghibli

All rights reserved.

First published in Japan by Tokuma Shoten Co., Ltd.

Shuna himself remains fairly ignorant of the world around him throughout; an early encounter with slave traders awakens moral outrage in him, but he does not learn more about the world through it. In fact, he is a surprisingly passive protagonist - he takes action, but he does not often make choices, reacting to events rather than trying to shape them. The final 1/3 of the book takes (what I presume to be) the transformation of the prince into a dog from the original story and translates it into the language of post-traumatic stress disorder: Shuna goes through too much, too quickly, and has to be nursed back into health (physical as well as mental). There are no quick cuts, no montage that takes us into the desired ending; it’s a long and grueling process of Shuna finding himself, with the help of others. This is a part of the story that many would skip over, or just pass it by briefly, but Miyazaki gives it his full attention.

This makes for a curious comparison to the artist's more self-assured heroes: those characterized by overcoming the adversity of new circumstances, which would come at a different stage in Miyazaki's career. Like Shuna himself, it is possible Miyazaki was still finding his way when this work came out. But also like Shuna, Miyazaki did not bow down to the world as it is, he went out and explored it - sought out new sights and ideas. It was not an easy journey, for either creator or creation, but it was well worth it.

* * *

- Which, to my great shame, I have not yet read.

- Neither the first nor second publisher I think of in terms of manga translations, although their usual young adult audience is probably a good fit for Miyazaki’s works in general, and this one in particular.

- By which I simply mean the panel occupies the whole page; this isn’t a Jim Lee pose-fest.