Writing about the most intimate specifics of personal experience is paradoxically that which makes that experience so relatable to others. In the case of Tom Hart and his shattering but ultimately hopeful memoir, Rosalie Lightning, the events immediately following the death of his toddler daughter are painfully private, yet his ability to relate them in an honest and even poetic manner creates a powerful aesthetic and emotional space.

There is no denying that my own personal and professional relationship with Tom informed my experience of reading the book. There are a number of other factors that also informed my reading. I have a daughter just a little older than Rosalie Lightning would have been now had she lived, and so she was in my mind's eye as I read the book. Both of my parents are dead--one passed away when I was thirteen and the other when I was an adult--and so I am acquainted with grief, loss, and mourning. I have also learned that grief, not properly expressed, can either eat at a person or else detach them from their emotions. Finally, in more recent days, I've come to understand the power of ritual as a cleansing and healing force that can be understood rationally but only truly comprehended and experienced as a matter of temporality and participation. Obviously, those who have never had a child, those who have lost a child, those who have never lost anyone or known grief, will feel different emotional tugs. That said, the structure of the book and the ways in which Hart expresses his emotions so plainly will stir in any reader an understanding of the connections which make us our best selves and the ineffable mystery of existence.

I've known Tom Hart through years of attending comics shows, where we warmly chatted about comics pedagogy and many other subjects. I remember a bleary-eyed morning at MoCCA one year after my daughter and Rosalie had both had tough nights, but Tom bore it with good cheer and his usual enthusiasm. A few years later, when I was organizing a small-press show in my city, I specifically arranged for him to come up to do a lecture. I was excited about what he was doing at his school, the Sequential Artists Workshop, and wanted to share his enthusiasm with everyone at the show. This was when his wife Leela Corman was pregnant with their second daughter—after Rosalie had died. Tom stayed at my house. I was struck by how much my daughter was drawn to him, wanting to play games with him, and how much he embraced the experience. There is a sequence at the end of Rosalie Lightning where Tom is exhausted from grieving and ritual, and a three-year-old girl at a party--whom he had never met--comes up to him and gives him a kiss on the cheek. He draws himself with an expression of sadness, grace and gratitude. Reading this passage, I thought of how generous towards my daughter he was with his time and emotional energy. She talked about his very brief visit for weeks afterward.

Hart hasn't published much in recent years, aside from the odd short story or minicomic, but I've long considered him to be one of the greatest of what I refer to as the Xeric Generation of cartoonists, those whose careers began in the early '90s. Along with John Porcellino and Megan Kelso, Hart was at the forefront of a kind of cartooning that valued immediacy over polish. Hart's work revealed his deep thinking about comics theory, especially in how it related to poetry and elliptical narrative techniques. In terms of balancing an advanced grasp of theory and structure along with a deeply humane and raw approach to understanding humanity, he's up there with Carol Tyler and Chris Ware.

At the same time, his narratives always center around politically and socially relevant issues and earnestly flawed characters. His most famous creation, Hutch Owen, is a homeless poet and philosopher, but even Hutch's archenemy, a developer, has a soul of his own. In books like The Sands and Banks/Eubanks, the characters are oddballs, outcasts and people facing disaster who ultimately find solace in others. In writing Rosalie Lightning, Hart turns himself and Leela into Tom Hart characters. He shows them the same kind of empathy, understanding, and room to express themselves that he shows his fictional characters.

One big reason for the slowdown in Hart's comics output is his work as an educator. Hart has never stopped thinking about comics, narrative, structure, poetry, and imagery and has in fact been writing a book about these subjects for quite some time (How To Say Everything). It is remarkable to see Hart essentially teach a master class in the form of this book on structure, theme, repeating visual and written motifs, and allusions to media of all kinds.

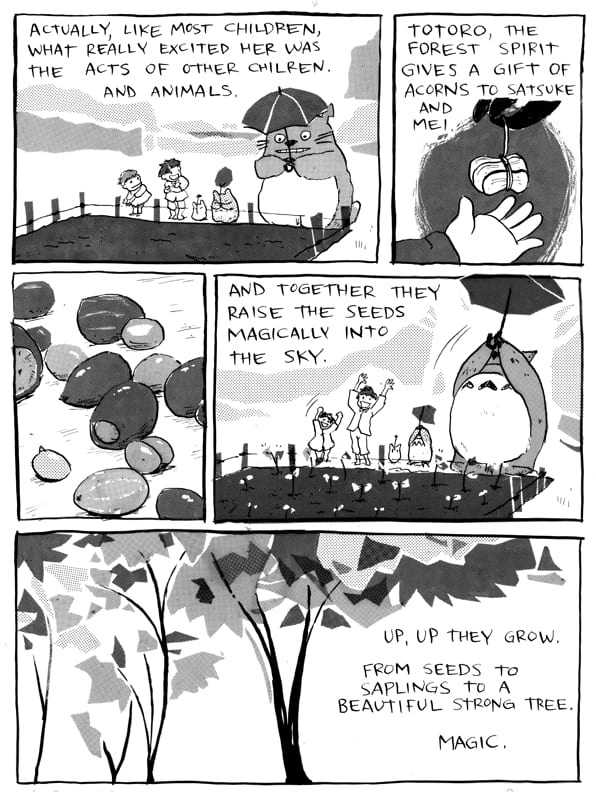

Indeed, the book begins with a direct reference to Hayao Miyazaki's film My Neighbor Totoro via the oak tree and the magical acorns that Rosalie was obsessed with. (Hart returns to this image several times in the book, most powerfully at the end.) Then Hart informs the reader that his daughter died in November of 2011. The rest of the book is a series of emotional and geographical journeys that he and Leela take as part of their grieving process.

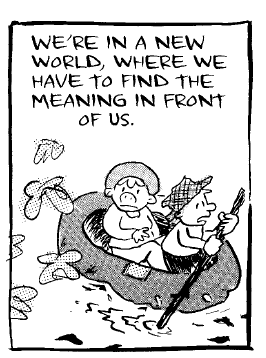

The immediacy and power of Hart's images have never been better. He uses a cheery, cartoony style in depicting scenes from the past. There's a recurring image that Hart shares of a man and woman adrift on a raft drawn in classic Hart style (cartoony but slightly grotesque, with sausage fingers and bulbous noses), in which he transposes himself and Leela onto that couple. In the present tense, especially in the beginning of the book set shortly after Rosalie's death, Hart's self-caricature is an inky, chunky, scratchy, jagged mass of lines that looks as much stabbed onto the page as drawn. Hart makes references to EC Comics, to the cartooning team Metaphrog, to George Herriman, to Gustave Verbeek's upside-down comics, to Osamu Tezuka's Astro Boy, Werner Herzog's film Fitzcarraldo, and to a single panel from a Chester Brown comic. Each reference builds on the next in how they personally speak to him regarding loss; for example, Astro Boy is about an inventor building a robot to replace a boy. The referenced EC story climaxes with characters falling into a huge hole, an image that Hart returns to repeatedly.

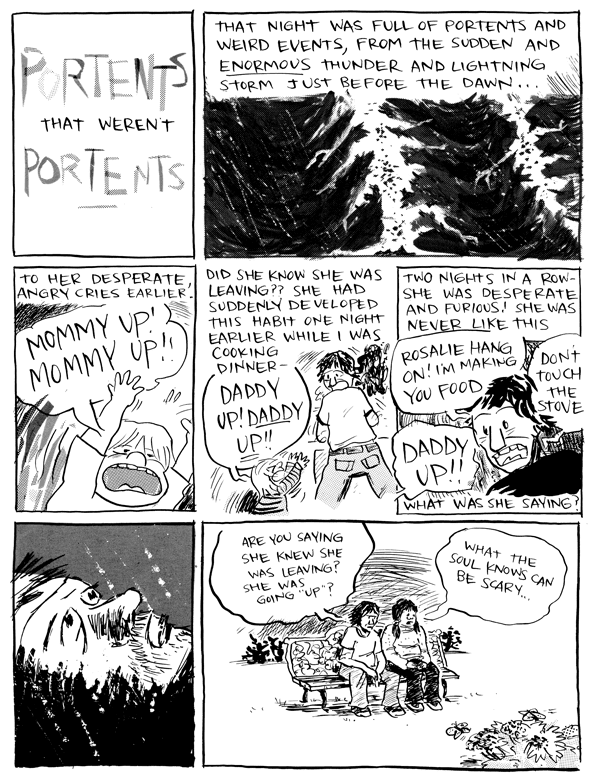

Hart avoids simply floating away on a stream of references by dutifully grounding the book in a pair of timelines: what led up to this family's move to Gainesville and what happened after Rosalie's death. The former narrative seems to be as much for Hart's own benefit as it is for the reader's, as though he thought it crucial that none of the details should ever be forgotten. It's a story of leaving New York, starting his own comics school, the bureaucratic nightmare of trying to sell a condo, the intense happiness they felt with their daughter, the extended time he spent with her in Gainesville while Leela was under a huge deadline crunch, and occurrences which seem to have been omens and portents regarding her death.

After Rosalie's passing, Tom and Leela traveled to stay with friends, went to a grief healing center in New Mexico, and finally journeyed to Hawaii to spread her ashes in the Pacific Ocean. Hart's processing of his grief in the present tense, as an artist, becomes a sort of third narrative: an emotional narrative that weaves in and out of time and emerges as the book's glue.

Hart believes that myths were created to help understand and process mysterious and unfathomable concepts like death and feelings like grief. He turns to art not just as a release, but as a way of forming his own personal mythology surrounding loss. The Metaphrog story he alludes to in the book depict's a quest to heal a sick bird. Fitzcarraldo is about the pursuit of an impossible goal. In one of the Verbeek comics, a tree viewed upside down turns into lightning, tying the central image of the book (the oak tree), even tighter to his daughter.

This sense of almost magical thinking informs how Hart depicts his and Leela's trip to the center in New Mexico. They are assailed by hail and sleet, as though their journey from the old steady-state of grief to recovery is going through a siege perilous passage, getting their car stuck in snow and then seeing angry dogs, the guardians of the threshold. In a scene depicting when others helped them push their car into a neighboring yard, Hart writes a typically blunt sentence: "I realize that for a few hours I haven't thought about throwing myself under a truck or driving into traffic or anything."

It's one of several times in the book where Hart returns from metaphor, allusion, and poetry to simply remind the reader what he is feeling. Another takes place at the center, where he talks about the deep reserve of anger that makes him want to knock down mountains. When the counselor suggests some kind of physical externalization of that anger, Hart succinctly notes, "But he doesn't know I do this, I write and I draw--it serves the same purpose." Channeling rage into powerful self-expression that is not just coherent, but rather synthesizes dozens of influences and types of thought, is at the heart of what powers the book. We may see the grief and loss and confusion expressed on the page, but the actual ink is pure rage.

This surprise those familiar with Hart's work. Anger has always been at the core of his comics; Hutch Owen is such an interesting character because of his righteous outrage at the injustices of the world. Hart here allows his own anger about his own personal injustice to guide him on the page. Hart has always balanced that anger with kind characters, offering a moment's respite or wisdom. The way Leela plays off of him as a character in the book is essential to the way that he allows himself to express his anger, because she's the more vocal one, the more openly emotional one, the one who exposes him to many ideas, images, and rituals.

One of them is the simple idea of sitting quietly in places like groves. This is part of an extended riff on the word "grief" and its derivations: "grieve," "grave," and "grove." When Leela suggests that they engage in more ritualistic practices, Hart starts referring to the quiet, meditative practice of sitting in a grove as "groving"--and his two characters lost in a boat set ashore. Hart repeats phrases and words (one of Rosalie's favorites was "Where did the big moon go?") to create emotional and thematic resonance just as deftly as he does with images.

There's no question that given the subject matter, Hart could have been ham-handed on every page and gotten a pass from many. Instead, he chose restraint. But his pent-up fury and pain comes through in a number of pages, partly as a result of the sheer cleverness of their structure. Take the page above, for example. On the prior page, he discusses simply laying on the ground with his wife and staring off into space, and renders a complete drawing of the park. He uses a bit of art theory regarding perspective and then devastatingly relates it to his grief by way of temporality. Note his scratched-out eyes, the idyllic and cartoony rendering of Rosalie from the past, and that morass of ink that represents a future that's impossible to imagine. As he goes through the mourning process, one can see that the way he draws himself changes, giving himself cartoony facial features with a greater line thickness than his more idyllic cartoons, and certainly not the dense scratchiness of the earlier drawings. This subtle variation gets at the heart of this book, does so while avoiding a pat set of platitudes. Indeed, it's a sobering exploration of the difference between mourning and grief.

Mourning is that practice of expressing grief through a ritualized set of experiences (e.g., viewing, funeral, wake) with an arbitrary but definite endpoint dictated by cultural and/or ethnic norms. Grief, however, is processed in dribs and drabs, frequently over a long period of time. Sometimes it is never fully processed. Grieving is a form of recovery, because it allows one to feel emotional trauma as an almost visceral, somatic experience instead of detaching from it and isolating from others. For all his grief and anger, Hart is pointedly never alone in this book. His and Leela's motto was "solidarity," but beyond that, the engagement and connection he allowed himself to have with his feelings is what allowed him to accept the care, compassion, and help of others.

The book can be described as any number of things: a prayer, a diary, an extended ritual, the act of creation used as as a way to face tragedy, a howl of anger and despair, and an emphatic display of gratitude both to those who helped him and Leela and the art that helped comfort him. It's an affirmation of connections, synchronicities, and serendipity, and allowing oneself to see and make these connections. Above all else, it is an embrace of the reality of loss combined with an affirmation of who was lost. The closing pages express grief in its purest sense: by not trying to forget the pain or the person, but rather by embracing that memory and admitting that Rosalie Lightning was here, that Yes, she was, and now she's not. In a series of drawings beginning with one of hers, Hart loops back to the magically growing acorns of Miyazaki, with an ever-more emphatic "yes" on every page. The minicomics version of this story that Hart self-published was titled RL, as though writing her name was too painful at that time. That's why the book version's full title is so important, because it's a reflection of that final anecdote, which is in itself a recapitulation of the book as a whole.