In 2019, Ed Piskor launched a YouTube channel, Cartoonist Kayfabe, with fellow Pittsburgh cartoonist Jim Rugg. The duo quickly won fans with their breezy, conversational approach to discussing their favorite comics. Their commentary hinges more on personal enthusiasm than critical rigor, offering insight into what Piskor and Rugg value as creators and what excites them. Among the most frequently recurring tropes explored on the channel is the concept of “outlaw” comics, a term originally coined by comics distributor Glen Hammonds to describe the violent black and white comics published in the late eighties and early nineties by the likes of Ken Landgraf, James O’Barr, and Tim Vigil, among others.

Since resurrecting the term, Piskor and Rugg have massaged it into more of a tonal descriptor. Their definition is slippery, but it tends toward works that traffic in stylized violence and offer singular or distinctive visual elements with an emphasis on transgression and subversion. Barry Windsor-Smith’s Weapon X, for example, is included under this rubric by their measure. “It’s very hard to define where these things fit. I always think it’s something that thirteen year old me would not want my mother to get hold of,” Rugg said on “Show and Tell 11,” an outlaw comics explainer episode filmed relatively early on in the channel’s run. “[A] lot of the outlaw comics, or what I think of as outlaw comics, have some kind of sexual perversion piece. Again, part of it is offensiveness, rawness, not for children,” Rugg continued.

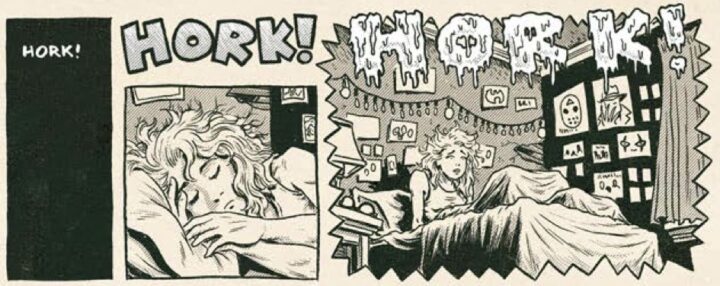

Offensiveness is the engine that powers Piskor’s latest, Red Room, a monthly series that delves into a seamy world of online snuff films. Whether it’s in his portrayal of stylized violence or his willingness to wallow in human misery, Piskor never passes on a chance to shock or disgust readers. Red Room takes its title from a maybe urban legend in which torture and murder videos are hosted on the Dark Web, an online realm of hackers, traffickers, and other digital n’er-do-wells. Each of Red Room’s twelve issues offers a self-contained story taking place within the book’s universe, featuring the stars of these films, as well as the producers, the victims, and the wannabes trying to find their way into the world. The title is described in marketing materials as “[A] cyberpunk, outlaw, splatterpunk masterpiece.” Piskor tries his best to match that swagger in his execution and even manages to deliver a few memorable set pieces. But when the blood and guts are washed away, there isn’t a whole lot left to be excited about.

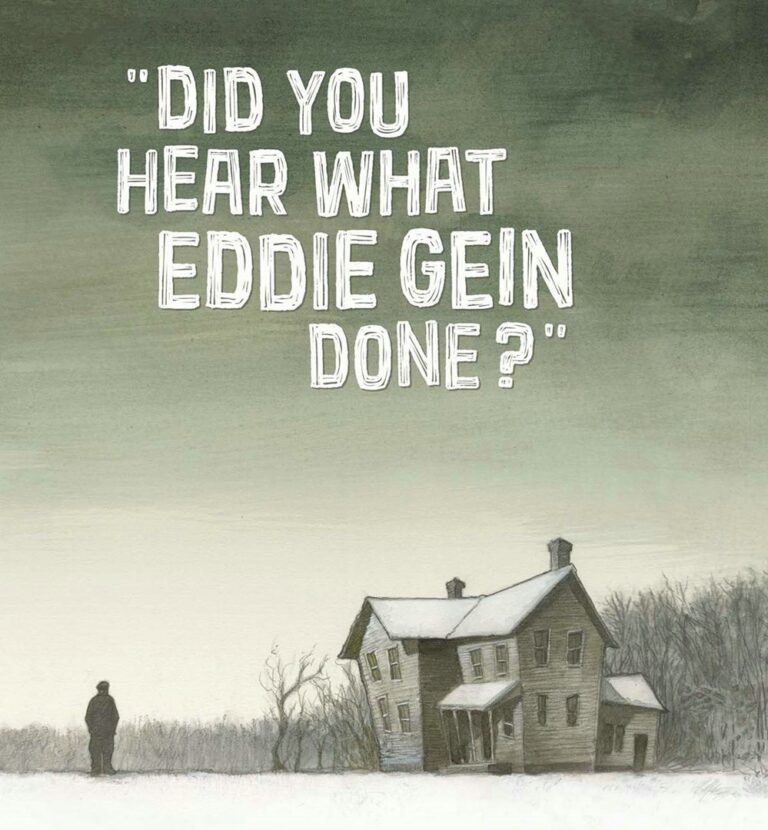

For all of Piskor’s slavish devotion to story mechanics, he does little to provide an overarching trajectory. Thus far, the closest he comes is in his packaging of Davis Fairfield, a small-town serial killer called up to the Red Room big leagues by Mistress Pentagram, matriarch of the Thelema clan, a cohort that is equal parts crime family and production company. Fairfield’s big break arrives on the heels of trauma, as his wife and daughter are killed in a car accident. Under Mistress Pentagram’s guiding hand and aided by her resources, Fairfield is introduced to the world of Red Rooms and blooms into a superstar on the scene. Bankrolled by his new mentor and benefactrix, Fairfield can handily provide tuition for his surviving daughter Brianna’s NYU ambitions, conveniently freeing him to pursue his creative endeavors. In Fairfield, Piskor offers a tidy portrayal of the sociopathic mindset that drives serial killers, but little else.

Overall, Red Room suffers for its sluggish pacing. Each story is zippy enough, but Piskor bills Red Room as the story of a universe. Four issues in and Piskor has done very little in the way of building a larger narrative. Characters from the “five families” profiled in these stories comprise the major players in the marketplace for Red Room snuff. To the extent that they acknowledge one another, it is at the remove of a screen or a monitor. Piskor pulls no punches in his efforts to shock and disgust with graphic, stylized violence and he delivers on that, but little else. While Piskor renders a detailed world, it is one that exists only as a site for this violence. It all feels pretty masturbatory.

A clear line can be drawn from Red Room to stylistic predecessors like Faust and The Crow. These precursors, products of the black and white boom that flooded the market in the eighties and early nineties were packaged cheaply, and replete with the characteristic errors of amateur publishing. This added to their charm. For all their flaws, it was clear the creators were doing the most with the tools at their disposal. The passion of creators like Vigil was deeply felt and lent the sum total the air of illicitness reserved for outsider art.

Piskor is successful in approximating the aesthetics of his source material, but the Vigil spirit eludes him. The all-important graphomania, duotone effects, and creative kills are all there. Flesh is flayed, torn, and tugged by hooks in truly creative, disturbing, and memorable ways. Equally jarring are the anachronisms that plague the whole of Red Room. Piskor takes great pains to portray realistic, state-of-the-art OpSec, yet dresses his characters like they’re extras on Barney Miller. Moreover, Piskor casts just about every character in their worst light, but, in depicting Black and Brown characters, he takes liberties that seem especially designed to court controversy, like when he translates a Black pimp’s mispronunciation of the word desk with an editorial asterisk on the book’s very first page. All of this seems meant to convey gritty realism, but in the reading it feels more akin to some kind of spiritual spoilage.

There are at least two barometers by which Red Room can be considered an unequivocal success. As the first issue goes to its second printing, it is clearly a commercial hit. It is also obvious that Piskor has been uncompromising in delivering something raw and unvarnished on his own terms. In issue four, when his character the Crypto-Currency Keeper describes the story as a “little ditty for your titties,” it’s because that’s an artistic decision that he made. Piskor has never been a stranger to controversy, and at this point, it’s a feature of his carefully curated brand. With Cartoonist Kayfabe he has a valuable platform with which to contextualize, justify, and advertise his many puzzling choices. But could Red Room have succeeded on its own merits without the bump from Piskor’s oft-touted Kayfabe Effect? Does it matter?