There’s a scene in David Cronenberg’s remake of The Fly where Jeff Goldblum, all hopped up on bug DNA, is unsuccessfully pressuring Geena Davis to go through the teleportation pods he invented. He describes her objections to this idea thusly: “You’re afraid to dive into the plasma pool, aren’t you? You’re afraid to be destroyed and re-created, aren’t you? I’ll bet you think you woke me up about the flesh, don’t you? But you only know society’s straight line about the flesh. You can’t penetrate beyond society’s sick, grey fear of the flesh! Drink deep! Or taste not the plasma spring, you see what I’m saying? I’m not just talking about sex and penetration, I’m talking about penetration beyond the veil of the flesh. The deep, penetrating dive into the plasma pool!” It is this bit of dialogue that provides the name of 2019’s Plasma Spring—a comic where Rutger Hauer desires to go back in time and take the Jeff Goldblum role in the film—the inaugural comics collaboration between Josie Perry of Scotland and Daphne Simons of New Zealand, after having met at an artist’s residency.

In these comics, celebrities are transformed into camp playthings, moved through a convoluted narrative involving time travel, poodles, hair care and sweat harvesting. The unspooling of this yarn has continued, at the rate of a comic a year, through two installments called Plasma Freeze, and returned to the Plasma Spring banner with 2022’s Halloweel, published by Australia’s Glom Press. All of these are Risograph-printed at 8" x 11.25", but have had their production handled by different presses. Previous installments are available as PDFs if you e-mail the creators. The main recurring character is Pauline, who is visualized obscured by a plume of smoke that encompasses her head and torso. In Halloweel the smoke clears and we see her face, which we’re told resembles that of a famous pop star, although I did not recognize the caricature. The explanation of the resemblance, we’re told, is another story, which will presumably be told in next year or two.

It could also have been told already, as there is a dimension of work outside the comics medium to Perry's & Simons' collaboration I have no access to. While Perry’s website documents a series of performances based on absurdist stream-of-consciousness narrative, it also shows impressive colored pencil drawings, all seemingly developed as part of this collaboration. (A gallery in the UK exhibited a full-color drawing of a scene depicted in Halloweel that's not included within the two-color book.) Without knowing anything about the creators’ other work, I can still infer what would draw the two of them to each other: presumably a shared sense of humor, based on an affectionate mockery of widely-exported culture. The humor is of a type familiar from drag shows, John Waters movies or the comedy of Kate Berlant: gay, in short, but not about an insider’s observed view of subculture as much as originating from an outsider’s tongue-in-cheek view of the mainstream. That means pasting the recognizable inside a mélange of degradation where all characters are basically horrible and, therefore, noting their low moral standing seems besides the point. The reader follows the story, though summary would be difficult.

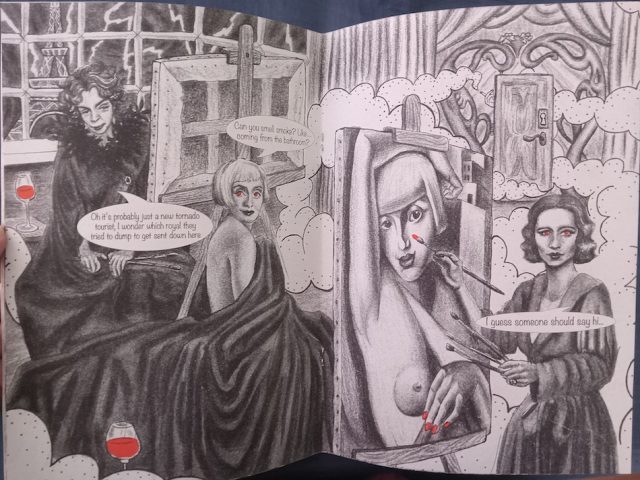

Halloweel expands the scope of what can be transformed, moving beyond movie stars and pop singers to take in art historical precedents. The surrealist painter Leonor Fini endears herself into the plot owing to a few biographical details - open bisexuality, and having at one point lived with 23 cats, the sort of fact funny enough that the mere statement of it feels like a joke, even if it sets up a later punchline. Fini gets worked into a plot which is a take on the “lesbian vampires” genre, and the precise mechanics of the vampirism are explicitly modeled on Octavia Butler’s Fledgling. This is by no means a genre comic, but it is a comic for people who appreciate genre as being an integral part of the mindset that makes no distinction between high and low culture.

Perry’s drawing places cartooned figures and photorealistic portraiture alongside each other. Both modes exist on a spectrum where caricature is somewhere in the middle, defining the meter by which the tale is told. The art is richly textured, feeling colorful even as the second color is only deployed as an accent. Primarily the story is told using double-page spreads, vistas of diorama-like composition that word balloons criss-cross to deliver exposition. In this installment, we get shots of computers with tons of text on them, and an appearance by Conspiracy Clippy, a paper clip that appears in the corner of a monitor when the research goes down a wormhole of disputed factuality. Here, it’s asking if the British royal family is actually eels in disguise. It is the balance between the manic narrative and the deliberate visual pacing that keeps the reading experience manageable, maintaining a readability even as the approach feels far from the perceived rules of sequential art. It could be there is a mutation in the DNA of comics at work. Dive in, drink deep.