Before the release of On the Camino, few cartoonists seemed less likely to publish a memoir than Jason. The Norwegian artist has spent decades creating deadpan genre stories defined by slapstick and muted emotions. 2013’s Lost Cat, for instance, approaches noir storytelling as if it were a mindfulness exercise, sticking to a rigid four-panel grid and a single repeating spot color. It’s a good book but not a warm book, and it conveys little about its creator beyond general impressions of his taste and sensibility. This makes On the Camino, Jason’s first autobiographical work, a major departure, and yet it retains most features of his previous comics—most notably the use of animal figures in place of people, including a dog’s likeness for Jason himself.

A reader might take the dog avatar as a sign the artist hasn’t abandoned the devices that earned him a cult following. Another reader might take it as a reason not to expect new emotional directness from Jason. They’d both be right. But if Jason appears to approach autobiography from a position of relative safety, On the Camino soon reveals itself to be a book about the distances between Jason and other people.

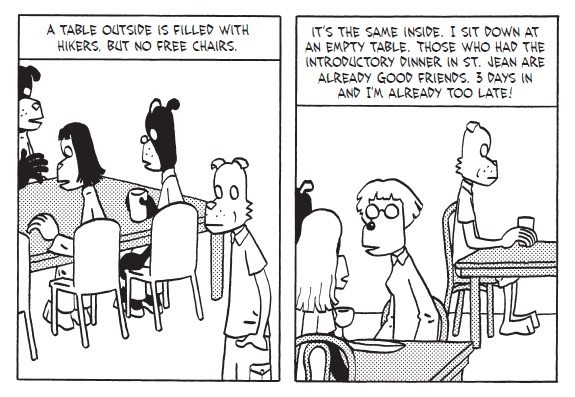

The comic documents Jason’s trip along the Camino de Santiago, “an historic 500-mile pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain.” As a travelogue, it offers a series of low-stakes, often charming anecdotes about the walk, its challenges, and its culture. But On the Camino is more moving as a document of Jason’s social longings and anxieties. The book begins with Jason on a train at the outset of his trip, urging himself to speak to other passengers. The first night on the Camino, he tells readers, “I eat alone [at a hostel]. I still haven’t said a word to another hiker.” The dog avatar doesn’t just create continuity with Jason’s previous books, in other words; here, it’s a constant reminder of the barriers between Jason and his surrounding world.

As the travelogue proceeds, Jason strains to be present during the trip and sees his fellow travelers bonding with greater ease. At a crucial stage of the walk, he mentions that, “I have no one to share the moment with.” The depth of this loneliness is anyone’s guess. The book explores it only as a series of moments, and for a memoir, On the Camino is coy about the details of Jason’s life. A reader who begins the book knowing that Jason is a cartoonist from Norway will end the book knowing that Jason is a cartoonist from Norway who recently turned fifty. But his personal remoteness is very much the substance of Camino. Jason-the-subject struggles to reach out to people, while Jason-the-artist carefully controls the depiction of these struggles. (There are compelling questions hanging over the book: whether he needs to be this way to create the work he creates; how much the personal limitations troubling Jason inform his talent for artistic economy.)

Reactions may vary about the quality of On the Camino strictly as a travel book, something this review can’t evaluate from firsthand experience. Alumni of the Camino might read the comic and find a lot they recognize and a lot they can’t relate to; Jason’s memoir probably doesn’t capture the walk’s full spectrum of emotional highs and lows. Even so, the book would be worth the trip solely on the strength of how Jason depicts the Spanish scenery. His previous book, If You Steal, sometimes reads like a showcase for its colorist, Hubert, and that book similarly deserves a read on the merits of its coloring alone. But throughout the black-and-white Camino, Jason’s line is the star. Drawing notable locations along the trail, he even allows himself occasional splash pages and a modest amount of extra detail. The result is a number of quietly beautiful standalone images.

Reactions may vary about the quality of On the Camino strictly as a travel book, something this review can’t evaluate from firsthand experience. Alumni of the Camino might read the comic and find a lot they recognize and a lot they can’t relate to; Jason’s memoir probably doesn’t capture the walk’s full spectrum of emotional highs and lows. Even so, the book would be worth the trip solely on the strength of how Jason depicts the Spanish scenery. His previous book, If You Steal, sometimes reads like a showcase for its colorist, Hubert, and that book similarly deserves a read on the merits of its coloring alone. But throughout the black-and-white Camino, Jason’s line is the star. Drawing notable locations along the trail, he even allows himself occasional splash pages and a modest amount of extra detail. The result is a number of quietly beautiful standalone images.

On the Camino is not short on gags or pop-culture references, either. Readers see Jason on the trail, quoting Christopher Walken’s infamous Pulp Fiction scene to himself, and later, imagining himself as the subject of a film shoot. He also passes through a quaint old village and imagines seeing Disney-ish fairy-tale characters. (Not all the gags are winners.) And when Jason first begins to feel kinship with his fellow travelers, a joke about Martin Sheen’s The Way (also about the Camino) is his way in. It’s a telling moment, and one that lends a possible context to Jason’s larger body of work. Any piece of art can be thought of as an artist reaching out to readers/viewers/etc., but after On the Camino, a reader might be particularly inclined to view Jason’s comics this way. His work has always treated genre and culture as a sandbox, but Camino suggests a desire for connection beyond the genre play—that Jason, despite the deadpan affect of his cartooning, wants a book like On the Camino to be a path he and his readers can share.