It’s funny how the size a comic is printed affects the way you read it. Obviously, the larger something is printed the easier it is to see detail within it, and seeing art that was originally reduced in size for print at the dimensions it was drawn at can be revelatory. But seeing Antoine Cossé’s new book, Metax, where his art is printed larger than any book-length project of his I’d seen it in the past, had me reconsidering the minimalist character of his cartooning and his oblique approach to narrative. I suddenly started taking in his individual images and apportioning to them larger amounts of time in how they were meant to be perceived. In being printed larger, at 8.1" × 11.3", the emphasis shifted from the reading experience of a book to the painterly creation of individual images, and—as those images depict moments in time—my perception of the length of those moments shifted as well.

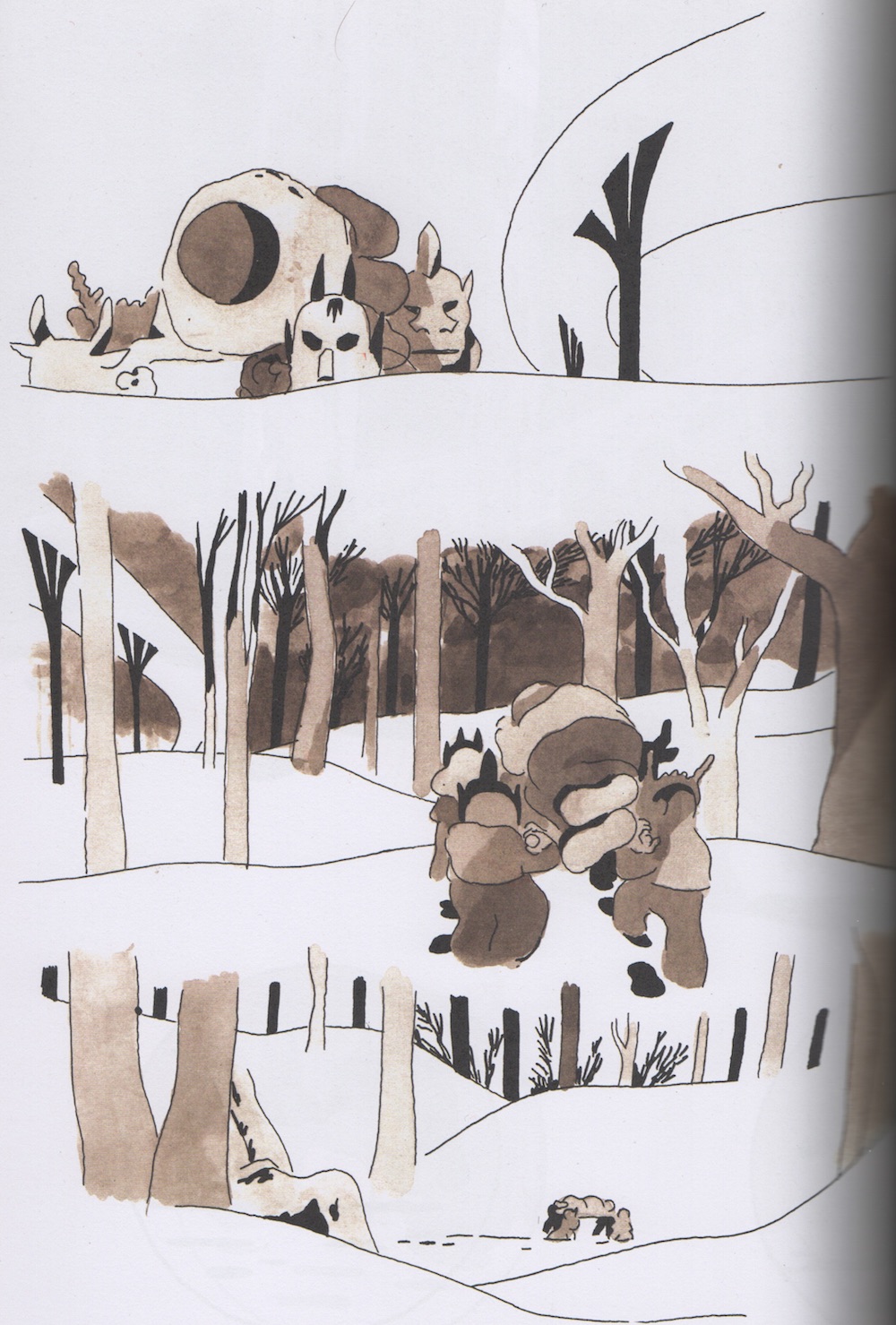

Cossé is already an artist whose work registers as painterly, even as it works as comics and feels rooted in the history of cartooning. His style seems particularly attentive to how, by blowing up a cartooned image, it transforms into something abstractly graceful. The frequent single-panel pages feel almost like enlarged details from a four-panel strip. The swoops and curves of his lines recall Frank King, but zoomed in 100 times. The gestures of cartooning, used to make recognizable symbols—puffs of smoke, motion lines, the scratches that stand for a tree’s bare branches—are deformed once more into something cryptic by being rendered in a broader brushstroke. You love to see his fat, marker-like line juxtaposed against more delicate forms and the texture of wash. There is a grace and calm to these images that makes them very easy to imagine working in a gallery context, or hung in your home. There’s a beauty to his images that has plain appeal.

Reading Metax, I felt the artist was trying to conjure up the sensations of “slow cinema” - films where it feels like nothing is happening for long sections of time besides acclimating the viewer into a dreamworld that cares little for urgency. There is a certain expectation I bring to a single page within the context of a graphic novel 300 pages long, of how much I think is going to happen, and Cossé often does distinctly less. This is fine, because of the visual pleasures being offered. With this book, it clicked for me that Cossé’s work may be more about landscapes that dominate an image than the characters that talk to each other inside them. An interest in landscape has always informed the plots of the books themselves: Metax is about dynamiting mountains to mine a precious metal, while 2016's Mutiny Bay was about a ship that crashes onto an island. Cossé’s story in Kramers Ergot 9 (printed at a size comparable to what we get here) took the enlarged cartoon form of a Bob’s Big Boy-style statue and made it the defining feature of the topography of a space. In Metax, you’re always encountering some fuck-off huge mountain, either rendered in wash or with its sheer outline defining the negative space of panel. These sculptural forms of swooping graceful curvature recall land art, and ask us to consider them similarly.

We register landscapes in terms of their scale, or course, on the occasions when we come across an impressive vista that enables us to take it all in. But much as a large-scale image holds our gaze, and slows down the reading experience within a comic, the form of a canyon is a reminder that geological processes takes thousands of years. Landscape exists on a different timescale than human lives, or character arcs. In Metax, the landscape is drawn, with the movements of mountains and melting glaciers delineated by the swoop of a hand, to capture their beauty and mystery, but drawing is a part of the comics-making process that takes exponentially more time to execute than the writing. A reader can be as awed by such shapes and forms as one would be in a walking in nature. Cossé shifts the emphasis of his comics onto these abstractions of line, away from story, so that the motivations of characters are deprioritized and left vague; but we’re left impressed by the forms that will still be standing after this generation of living animals passes on.

This is not to suggest the book is boring: translating these phenomena to comics requires some rejiggering. The landscape in Metax is a magical one, with a weird disease that occludes eyeballs with the patterns of a starry night sky. And while one might come to know the shape of a space by how the wind blows through it, here the wind is generated by a motorcycle, turning itself into a blur as it achieves high speeds. There is a plot here, and certain plot points that fit into a genre framework. It’s a political thriller, of sorts, within a fantasy kingdom. People take pills that turn them into birds. The king’s horses are shot down with rifles.

The total aesthetic experience of the comic takes precedence over the creation of a plot that would appeal to fans of the fantasy genre. If, at the end of the book, I’m not really sure exactly why things occurred the way they did, that’s not necessarily a flaw but a challenge the work has deliberately presented. Because the reader controls the pace of the reading experience, a shift towards slowness never feels confrontational the way it would in a cinematic context. It just feels leisurely. A shift in approach away from a storytelling tradition that favors clear character motivations, on the other hand, is going to result in a degree of narrative opacity that feels a bit more like a dare.

The narrative does not provide a sense of escalating tension in order to keep the reader turning pages. While there are six-panel pages, where events and dialogue occur to explain the relationships between characters that constitute this world, there are far more pages consisting of just a panel or two, and very few words. When something happens, it emerges from an overture of shapes, and then dissolves again.

Even when the text on a page is limited to numbers signaling a second-by-second countdown, I don’t think we are meant to breeze past these images, as one would in “real time” were the scene unfolding cinematically; we are instead to consider their significance. The moment being captured in a panel never feels defined in its duration by the text inside that panel. If the normal experience of reading a comic assigns to a panel the amount of time it would take for the text to be spoken aloud, as the image being drawn would only be a brief instant inside that larger moment, in Cossé’s comics that’s flipped. Small amounts of spoken dialogue hang in the air while the readers decode vast amounts of unspoken history. NWAI, a comic Cossé released in 2014, similarly had minimal text, eventually revealed as a voicemail message, but every spread felt like it was meant as a rumination on memory, with the past preserved in miniature inside the wreckage of the present. A voicemail takes a moment to record, but the time encoded in an image spoke to both an extended relationship and the devastation wrought by its aftermath.

In the absence of narrative urgency, it is easy to dip in and out of this world, and that’s in part due to the sense of significance being suggested. One can walk away from it the way one would a painting that evokes questions without offering answers, and one can dive back into it the way one does a long-running comic, where you puzzle over the continuity you’ve missed. One of the characters in Metax is Harold, the title character of another Cossé comic, published by Retrofit, that’s also featured in a comic Breakdown Press published called J.1137 that I only know about because of a review on this website. I can’t really work out what the deal is with this character, or fit the two comics I’ve read into a shared universe that makes sense in terms of chronology.

What we get in the pages of Metax does not constitute a system unto itself that contains explanations and justifications for all that we see. There are characters that, to the best I can tell, do not contribute to the overall plot at all. The book is named for a precious element that has allowed Ronin City to grow in prosperity. No new Metax has been discovered in years, to the consternation of the kingdom and the people they employ. Meanwhile, a terrorist organization is attempting a coup, of sorts, aiming to end the kingdom’s reliance on Metax. This terrorist organization uses the Metax to heal themselves and to turn themselves into birds after committing acts of terrorism, because they have access to the undiscovered-but-rumored-about garden where Metax is abundant. The sequences showing this area, introduced two-thirds through the book, are the only ones in the book that contains color.

It’s an interesting use of color, in that it’s almost purely conceptual: The presence of color is used to signal the idea of “color”, relegated to one location featuring multicolor highlights as a point of contrast to the sepia brown of the majority of the book. There are other comics of Cossé’s that do something similar, the aforementioned NWAI being one of them. Color is a very powerful visual tool, and Cossé uses it incredibly sparingly. This dialed-in restraint feels like the core of his project, because he is deliberately not using color the way other people use it. One of the main ways color is used in comics traditionally is to make a character pop, to separate a figure in the foreground from the landscape or background. That’s because the value system of most comics distinguishes between the two of them in a way that prioritizes characters. By configuring a visual schema where that is no longer a worthwhile distinction, and people are merely phenomena that exist within the world being presented, color is left to instead represent Something Else: the presence of the unearthly and miraculous within an otherwise integrated context.

An engineer, kidnapped by terrorists and brought to the garden at the climax of the book, is ecstatic. One would think he wouldn’t be, based on what we know about characterization, how people are defined by the work they do and the people they are in service to. But in the garden, surrounded by glowing color, he becomes a silhouette: a form of pure line and shadow. He exults, dancing, embracing the contours and gestures of a body, rendered in Cossé’s brush, a celebrated thing inside the schema of his world.