What one believes and what one can prove are two entirely different things, but it is in the space between them–be that a yardstick’s length or a yawning chasm–that the world’s truly interesting and challenging artists ply their trade.

Perfect example: we’re nearly six years on from the release of Austin English’s Gulag Casual and people are still delineating, deciphering, in some cases even decompressing its thematically heady contents. And while I’m not one to disabuse the constitutionally pretentious of their hobbies, dare I suggest a big part of that book’s genius was in its ability to warp/mold fairly straightforward artistic statements into a form that would make those who derive a good chunk of their self-worth from analysis and critique feel like they’ve accomplished something - if only by formulating a cogent reading of and response to it. In short, it made assholes like me pat ourselves on the back for figuring the book out, or at least thinking we did.

In retrospect, though, one strike Gulag Casual had going against it–one entirely beyond its control–was its release as a single title among several in a publishing “season” bundled together by 2dcloud, which meant a good number of readers (certainly everyone who backed their Kickstarter) received all the publisher’s offerings for the year in a single package - and, as a result, understandably ended up reading all or most of them in a fairly compacted time frame. Less understandable, however, was the impetus to somehow insist that there were sub rosa thematic connections between all the 2dcloud books released in a given year - or, even more preposterously, to intuit that the various works were “in conversation” with each other to one degree or another, simply because they were shipped in the same fucking box. This was in the early days of the term 'curation' being stretched well beyond its breaking point, and if I recall correctly (always a dubious proposition) people were looking for any excuse to just say the word.

Now, of course, all variations of 'curate' have been scraped clean of meaning completely, so it’s just as well we not use it in this case, as English’s latest work, Meskin and Umezo, has been put out into the world via the cartoonist’s own Domino Books imprint, in the manner it deserves and demands to be considered: entirely on its own; apart from the rest of the crowd; well and truly independent. Why, if you look, you can even see it off over there in the corner, carving out its own space - and interestingly enough, it’s a space that completely nullifies the very idea of it being in “conversation” with other works. While Meskin and Umezo contains references aplenty to people and things outside itself, it is still undoubtedly a singular, discrete product of English’s imagination.

Four-plus years in the making and fully-painted, Meskin and Umezo is an impressive achievement just as a physical object, but I’ll tell you this much right now: there are people who are going to get lost in this book. And that’s okay - they’re the sort of folks who you wish would get lost in general. Anyone who hasn’t picked up on the fact that the annihilation of pretense is a recurring theme in English’s overall body of work, and instead uses it a springboard to micro-analyze every decision and reference peppering his visually and narratively loose/abstract comics, is not only running the risk of having their 'astute reader' badge suspended, but is sucking the fun and vitality out of their own reading experience. Don’t let them get away with ruining your good time too. English’s comics are challenging, dense, and singular, to be sure, but they also offer an entirely coherent and satisfying surface-level reading that tends to get lost in the weeds the more one overthinks it. And therein lies one of English's greatest strengths as an artist: he’s really good at hiding things in plain sight.

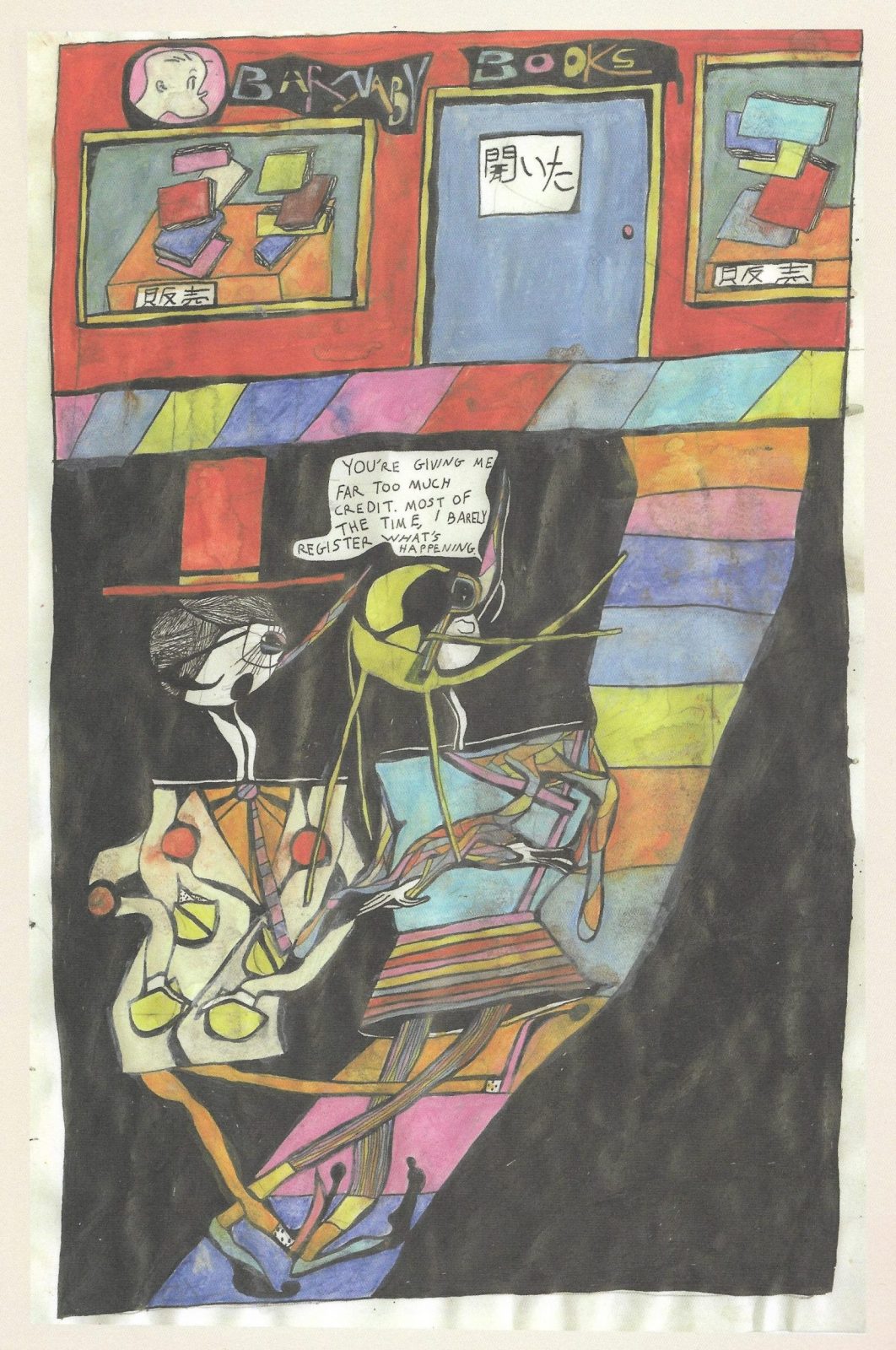

Our story particulars for this one, such as they are, revolve around acquaintances/nominal “friends” (Mort) Meskin and (Kazuo) Umezo (or Umezu, as I’ve usually seen it) getting together once a week for drinks, conversation, shopping, and a general lack of coherent communication. Their strained interactions are observed from without by two parties: sympathetic Ramona (Fradon, I’m assuming) and antagonistic Wayne (Boring, at a guess), both of whom are invested in what our protagonists are doing to a degree that can most generously be termed 'unhealthy', even if their reasons are entirely their own and polar opposites. There’s a bit of the classic Joycean “Dublin walk” happening here, but filtered through a decidedly askew sensibility that, in a pinch, can be called avant-garde - provided one doesn’t mind giving a legitimately auteurist approach to the medium the short shrift.

What’s almost fiendishly clever is not that English names buildings and businesses after the likes of Robert Kanigher, Mort Weisinger and Crockett Johnson’s Barnaby (although, what the hell, such little creative flourishes are fun), but that he manages to weave his central thesis about the inherent deficiencies of both communication and observation into the metaphorical DNA of the comic itself, openly acknowledging that never the ‘twain shall meet while utilizing tools that can’t help but come up short, because - hey, what other choice is there? I’m reminded, to a certain extent, of anarcho-primitivist broadsides against the concept of language that are nevertheless stuck using words to make their point; this is art that actively explores the limits of what art is capable of, both from the standpoint of the artist and from that of the audience.

All of which makes this an ambitious piece of work, sure, but more than just that it’s audacious - by means of form and function, English questions each simultaneously, and nobly refuses to render a verdict when all is said and done. Along the way his characters lapse into speaking in other tongues, and physically bifurcate, trifurcate, quadruplicate - but it all feels, for lack of a better term, 'natural', since even in singular form these characters' consistency of appearance is limited only to the most general, easily-identifiable traits, such as hair color or the hat they’re wearing. All is otherwise in flux; this is a general through-line for each member of our ensemble from first page to last. There is a default sense of consistency in terms of who they are - but what they are is up for grabs at any given moment.

For all that, though, I’d be lying if I said this was in any way a confusing book; it’s just a chaotic one. But even that chaos is held in check by the underlying notion that, regardless of circumstance or surroundings, some essential and irreducible core of self animates the thoughts and actions of all of these people - even if they can’t articulate what that is to themselves, much less to each other. And therein lies that “secret hiding in plain sight” I made reference to a moment ago, which Meskin and Umezo struggle with as they attempt to define what makes a “perfect enemy” - it is, of course, ourselves.

All forms of communication and observation–art included–are of limited efficacy because our perceptions are limited. Our horizons, by definition, can’t extend beyond what we’re capable of imagining, and our ability to make what we imagine a reality is likewise encumbered by obstacles both internal and external. “We are who we are” needn’t be a defeatist credo, though - after all, Austin English has used it as the conceptual basis for 2022’s first bona fide comics triumph.