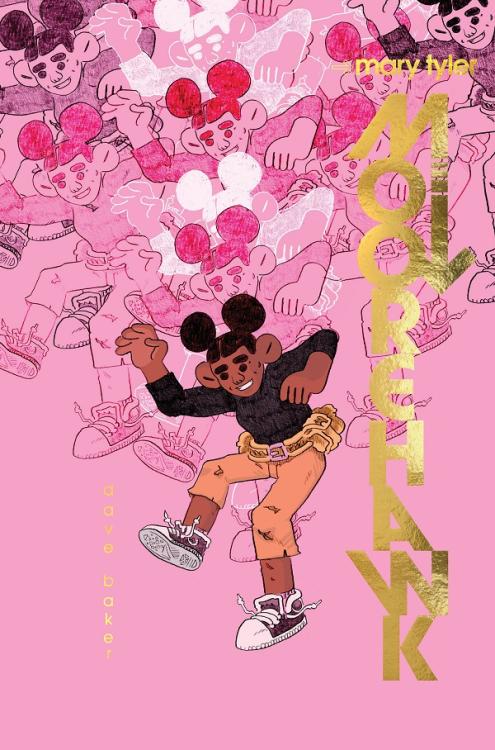

And so I have just read a book called Mary Tyler MooreHawk by the cartoonist Dave Baker—with photography by David Catalano and "design, layout, photo manipulation and additional photography" by Mike Lopez—published by the warhorse Top Shelf Productions. Took longer than I anticipated, truth be told. You should probably set aside a big chunk of time to hack your way through, should you decide to take the plunge, because whoa mama - this book has a lot of words in it. It is not, I would say, purely a comic book. There is much comic book here, yes, but there is also much in the way of text.

Well, well, well, says I, if it isn’t my ancient foe, prose fiction.

It’s a dense read. The book alternates between sections of comics and sections of prose, with the purpose of the latter (roughly 100 pages of the book in whole) being to provide gradual context and insight into the former. The comics are often bewilderingly dense, overstuffed with detail, rewarding a deliberate reading speed. The extended prose sequences that buffer the comics also act as a brake, forcing the reader to progress at a more stately pace than they might otherwise.

For all that the intersection of prose and comics sometimes feels like a fraught border, Baker’s narrative allows these disparate means of story-making the opportunity to meet somewhere more amenable. By which I mean, Mary Tyler MooreHawk fixates almost to distraction on an important commonality between the two modes: the ways and methods by which the bookmaker attempts to manipulate the reader’s pace. This is a matter of primary concern for the cartoonist, concerned as they must be on the velocity with which the ideal reader can be induced to turn the page. Comics read “fast” or “slow” based on a number of factors, not least of which being how many words can be found on the page, how effectively action is conveyed, and how many actions are depicted.

Prose fiction operates on a different time scale than comics. A prose novel is, in the classic sense, a kind of cattle chute, pushing the reader one way down a narrow and dark tunnel, possibly with an explosive epiphany waiting at the end. The writer of prose simply does not have as many tools to vary pace as a cartoonist. Certainly, there’s the push and pull of small and large paragraphs. The writer of potboilers knows how to pull a reader along like they’ve got a hook in their mouth. For instance: I started this review with shorter paragraphs, in order to suck you in by giving you the sense of achievement that can only be gained from conquering shorter paragraphs. Reading Mary Tyler MooreHawk, I felt very strongly that I was being pulled through the story at the pace of a novel, utilizing novelistic techniques such as those described here in this long paragraph. For instance, again: if I’d started this review with a longer paragraph like this, you’d have gotten bored and wandered away to get something from the kitchen. Whereas you have a bit more stamina now that we’ve built up to it! The immediate sensation of reading Mary Tyler MooreHawk brought to mind an experience like Danielewski’s House of Leaves. Not a comic book in any sense, and yet at the same time more concerned with the construction of meaning from reading procedure than most conventional prose. Tearing apart that cattle chute, finding common cause with the humble comics. What, after all, is comics other than an open referendum on the construction of meaning from reading procedure? A more open toolkit than the prose stylist, as I say, especially if you also embrace the tools of the prose stylist.

Think about the bias against wordy comics that has sprung up in recent years, especially in more mainstream and mainstream-adjacent spaces, where the specters of Claremont and McGregor haunt the phantom spinner racks of yore. And what are people so afraid of, really - a comic book that takes longer to read than taking a shit? Friend, it must be said: some of us need more fiber in our diets. Go too far in that direction, however, and one ends up in the back half of Cerebus, parsing through long passages about the spiritual benefits of misogyny which we are informed, somehow, will add context to the funny aardvark flying through space on a rock.

The prose sections of Mary Tyler MooreHawk tell a story about a future, well over a hundred years from now, in which it is illegal to own most physical objects. A loophole in the system inspires the creation of a television studio to serve the market for home viewing, demolished by the establishment of communal televisions at some point in the past. But, it's still legal to own dishwashers, and dishwashers have screens. Therefore, this book posits as the final frontier of home entertainment watching TV shows on the touchscreen of your kitchen appliances. "Mary Tyler MooreHawk" is the name of an early program broadcast over this strange medium, a fantasy adventure story about a girl at the center of a clan of scientist adventurers. She’s got a robot brother and a slightly frosty stepmom and they hobnob with all matter of demons and extraterrestrials. A rich stewpot of genre signifiers from across the previous century.

A thought that occurred to me throughout the process of reading: would the comics sections stand on their own without the scaffolding of the prose to buttress? I have no ready answer to this, but it’s always worth asking for any polyglot text: what is gained and what is lost when different modes mingle? In between the comics we are given excerpts of articles from "Physicalist Today," a future magazine devoted to the collection of physical objects from the past. A wholly illegal business, at least in the present of the story’s narrator. The reclusive mastermind behind "Mary Tyler MooreHawk," himself named Dave Baker, is a “physicalist” of no small renown, and it’s from those historical influences that the shape of the fictional story emerges.

Incidentally, if you suffer an aversion to books wherein the author appears as an important character, perhaps Mary Tyler MooreHawk is not for you. For all the ideas on display here, a rich tapestry of notions and assertions strung together with displays of quite excellent cartooning ability, it is still at times overweening in its dedication to cute, in the most derogatory fashion. It’s a book built on the enthusiasm of its creator to an admirable and at times suffocating degree.

What emerges from the book is an artistic lament for the idea of scarcity. We have everything here, right here, at our fingertips, streaming out of the little box in the hand you’re almost certainly using to read this review. Possibly while also lamenting the lack of fiber in your diet. Frankly, it’s a nightmare that we’ve become so used to it. You used to have to look for things, to search and find and construct your own narrative about the past in the shape of your own curiosities and proclivities. If that sounds like old person whinging - well, there’s some of that, certainly. Because the old ways were fun. Life was more like a scavenger hunt in the days before Spotify could draw a diagram of your interests for you.

Of course, Google doesn’t work anymore, so we may be getting some of that old spice back whether we want it or not…

Is that the future Mary Tyler MooreHawk offers us? A view of a world where the curtain has once again been closed, the artist unrevealed, the celebrity industrial complex around cultural product dismantled with finality? Despite many signifiers of dystopia peppered throughout the book, there’s an element of hope in the totemic accumulation of physical objects as a symbol of connection and continuity. This seems very pressing, with the infrastructure for streaming being torn down across multiple industries and the significance of the physical object once again sneaking into the discourse. There was never much in the way of revolutionary potential in consumerism, but antiquarianism? The impulse in its most naked form stands at an abstruse angle to the relentless drive towards rentier feudalism that corrupts every aspect of modern life. Let us all own pieces of our past as a means of keeping that past whole. Putting together a multimedia oral history of a weird television show that barely lasted one season and that no one else watched is the kind of thing people used to do, back in olden times. Perhaps, Baker posits, it's the kind of thing people will one day do again.