It must be stated up front that Kramers Ergot has made life far too easy for critics. Anthologies are often difficult to analyze, because most of them wear the pragmatic limits of their creation like flimsy invisible dust jackets. It is not uncommon, I think, for editors to surrender to chance when putting these things together; you can hook up with however many contributors you want, and coordinate as best you can with those contributors you want to pursue, and reject, in the face of plenty, those submissions you can't use, but to an extent you are at the mercy of what you are given. And indeed, there are anthologies most succinctly described as 'what was given.'

Kramers, however, has long offered a pillowy slipstream on which the featherweight may drift behind; in this group I include myself. Who could forget the technological acuity of Kramers Ergot 4 (Avodah Books, 2003): production so sharp that you were bade not only to read stories-as-stories or factor drawing-as-drawing, but to consider textural components and the play of media – and, implicitly, the character of reproduction itself in art primed for mass distribution? You could ride that breeze all the way to Kramers Ergot 7 (Buenaventura Press, 2008), a toddler-high harassment of bygone-Sunday-funnies dimensions, then crash bloodily to earth with Kramers Ergot 8 (PictureBox Books, 2012), as gnashing a howl of despair at the futility of it all as I've seen from a high-profile comics anthology. It's not that you can't also evaluate the strengths of the contents therein, but there is a unique character to the various Kramers that afford a ready chassis for review.

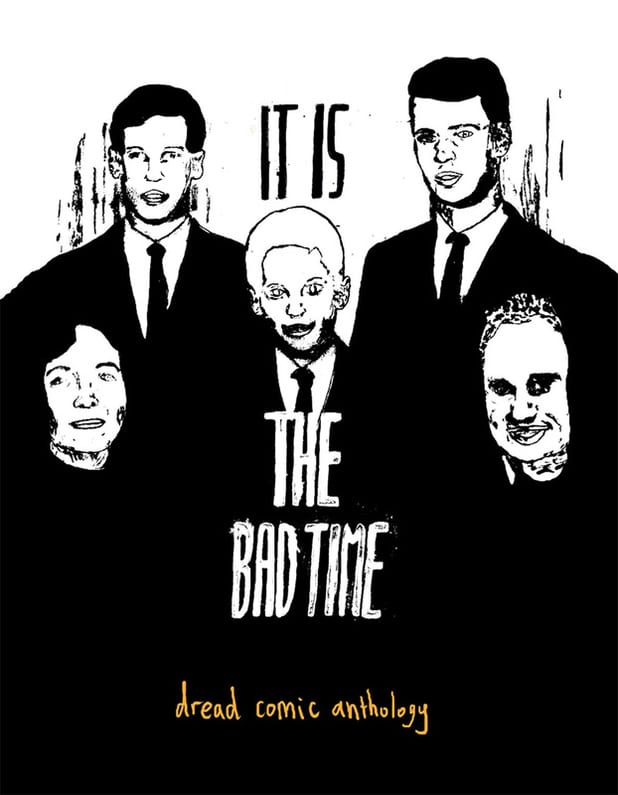

So what the fuck do you make of Kramers Ergot 9? The book is bedecked with mottos: “ROT IN HELL” says the front cover, “WAR & PEACE” says the spine. The legal title of the book, per the indicia, appears to be “Kramers Ergot Vol. 9: Evil Fully Determined”; all aggressive messages, but also, perhaps, mocking the idea of this book carrying anything upon which you might latch as a fixed message. With its sturdy, multi-colored pages and 9” x 11 3/4” phonebook-like dimensions, Kramers 9 deliberately hearkens back to its fixed size of the mid-'00s, though niceties such as page numbers and a traditional Table of Contents are now included. Where once Kramers seemed restless in terms of format, it may now be characterized with some yen for stability, or even a desire to recapture the feel of the series' heyday.

But these are simplistic poetics, and while Kramers 9 is probably the most difficult-to-classify of the volumes since Kramers Ergot 6 (Buenaventura Press, 2006), it is nonetheless shot through with continuing themes of illusion and mistake: perfect for an American election year. The whole affair starts with a Steven Weissman story in which a Native American rider surveys a mighty canyon, searching for his Silver Medicine Horse. Pictured often in long shot, dabbled by shadows among high rock walls, the hero recalls Jesse Marsh's Tarzan in a landscape stripped of foliage, though this man is hardly in control of his environment. He is stranded by a storm, menaced by a big cat, and bitten, finally, by the Silver Medicine Horse, which was demonstrably never in his control. Perhaps the horse is fate, laughing at the hero's projection of confidence and stranding him in a dark cave of uncanny secrets.

Similarly troubled are Jay and Kay, the frequent heroines of comics by John Pham, who's been doing his best work in recent issues of his Epoxy series. In those books, comics are bound inside of comics, so that Pham's style shifts as the reader draws closer to the center, growing more text-heavy and cartoonily humorous as the pamphlets-within-pamphlets become physically smaller. There is no such context in Kramers, which throws the satiric qualities of Jay and Kay into sharper relief: hug-prone best buds, they are generally unable to deal with the realities of life despite the support and positivity they offer one another, which mainly serve to reinforce their preconceptions. Here, googly-eyed as ever -- Pham drawing as if contracted by a distinctly saccharine children's magazine -- the pair explore a scary graveyard in search of a lost child, eventually discovering that the local monsters are actually homeless people, some of them veterans of war. Yet despite the innocence of the heroines' misunderstanding, not all of the locals appreciate their intentions; their fussy care for others is ineffectual, and arguably selfish. There is little to do but return to their own home, which which they are at least familiar.

Immediately following is “an excerpt from 'Discipline'”, by Dash Shaw, who has jettisoned color and paneling altogether to create pages of images that slightly overlap at times, giving the sensation of time displaced, which can be interpreted here as recollection. War again figures in, this time finding soldiers in the midst of friendly plunder, entering homes in occupied areas to collect supplies. “There is no non-military demolition,” we are told in cursive handwriting, an epistolary explanation of civilian relations from the front. Quickly, the writing falls out of sync with the pictures, as householders posing as cooperative fire upon the departing troops from a distance. Their resistance has them burned alive, their house torched, while the narrator (perhaps among the injured) segues into a philosophical discussion of goodness as an active principle: “Each man is his own scale weighed, and the lean of the scale is his own ray of light.” It is bleakly ironic, this play between the concrete character of written ideology and the revelations of drawing-as-memory; Shaw closes on a wounded man's eye, gazing toward the reader.

Not every contribution is so grave, but characters throughout are rarely wise to trust their assumptions. Kim Deitch, of course, is an old hand at this, whipping up another chapter from his personal history of disposable-culture-as-hidden-myth, this time concerning the White Jungle Hero trope; a young boy's messianic and bestial destiny is sidetracked by societal intervention and electroshock therapy, with only the prospect of reincarnation looming as the salvation of his desires. But preceding it is an alternate and far more severe rendition of similar themes, from the always-striking Lale Westvind. A cosmic doom ballad slathered in the colors of rotten fruit on a blazing summer's day, “The Knibul Ball” plays out like some very tainted ink seeping into the Charlton press, a chorus of talking animals marveling to the story of an aimless drunkard handed an eyeball key (“real kitsch”) and wandering into a ritual of self-mutilation and mutual flesh-eating with strange beings for purposes of intermingling pain toward a greater empathy. But the weight of violence is such that she cannot continue, and she is reborn a scarred jungle heroine, living among beasts and their unconcerned appetites while waiting to die.

And then, a little later, you might catch reflections of all of this in a wholly unrelated story, an untitled piece by Manuele Fior. On a class trip to Paris, a tutor cannot help but notice her class's disdain for her stern and intellectual ways. A colleague narrates the discrepancy between the ideal of a place and the reality; the tutor lectures casually on the swarming reliance of people on each other, at which point her purse is stolen. Yet before long she has abandoned her work to wander the city – to confront the illusion, or to submerge herself within it? There is another story, a one-pager by Julia Gfrörer, in which a woman appears to be talking to nothing at all, for the benefit of her child. There are seven tiers of panels. The first three concern her address, and conclude with her eyes being closed and ghouls stealing the child. The next three concern her flight, real or dreamed, literal or allegorical, as she digs the child up breathing from a fresh grave. The final tier dismisses her entirely. The child has grown. She falls and cries, but rises again. “Well, she was so young,” a voice says from off-frame. “I'm sure she doesn't even remember.” Is this her mother's legacy to her?

Yet I am risk of becoming trapped in impositions myself; this is not a hard-and-fast theme of Kramers 9, just a striking commonality among a good number of the pieces. Some of them are just funny jokes, like those of Andrew Jeffrey Wright (an escalating war of art between graffiti punks and a very inspired janitor) or Ben Jones (a spiraling bit of slapstick, read in a Brian Chippendale-like coil). Some of the better of them are expert slices of life: Gabrielle Bell accompanying her mother on a richly-observed adventure in home-buying; Trevor Alixopulos tracking an eventful night in the life of a punk stumbling adjacent to a 'respectable' future. The level of quality is generally pretty high, though I don't think there's much in here that feels avant-garde or particularly transgressive re: the boundaries of the medium. That's an expectation built chiefly by the formidability of the series' prior numbers, but it's good to expect a lot.

Still, to my eye, since Kramers 8, what is unique about the series is the restless sense of anxiety in its stories, as if the book is preparing for calamity. Throughout, people are unwilling or unable to successfully navigate the world. Anya Davidson (a welcome source of bold, hot colors) offers a short biography of Hypatia of Alexandria, seen first rejecting the sensual abandon of the Earthly plane, only to be murdered via the convenient metaphysics of religious and political conflict. Michael DeForge is vicious -- always underrated, him, for his viciousness -- in depicting the rictus of a college boy suspended in a social media bubble of false, commodified emotion, the program literally sucking his dick and telling him it loves him while presenting emails as delicate chicks and wiki searches as animals gutted in a field, their entrails read and spilled to help the boy slide by in class. I am never unhappy to see new work by Antoine Cossé, who shows a motorcyclist couple making love in a gigantic statue, like a tacky restaurant mascot, revving up their ride until they explode into the sky, their guts spatting onto the side of a passing tractor-trailer. For what were they searching? "We made it," the woman says, before they are annihilated.