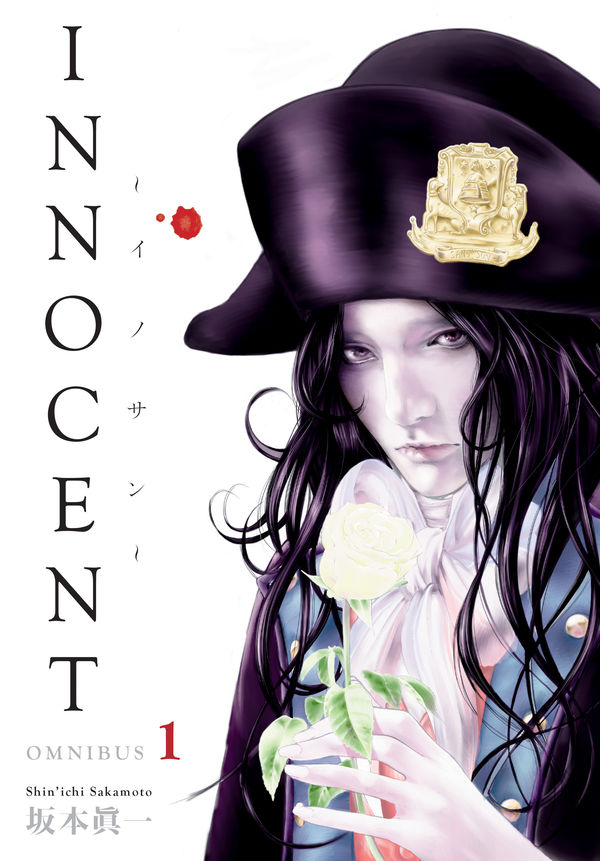

Innocent is a seinen manga by Shin’ichi Sakamoto about a really hot sadist who is constantly crying because he doesn’t like doing sadism. But this is not a comic about bondage; rather, it's a historical fiction about state killings and the much less fun version of torture than the recreational fetishes such violence inspires. Adapting The Executioner Sanson, a 2003 book by Masakatsu Adachi, Innocent (which ran from 2013-15 in Shueisha's Weekly Young Jump) is based on the life of Charles-Henri Sanson, royal executioner of France under Louis XVI and later the high executioner of the First French Republic: a sensational and bloody role carried from monarchy to revolution. I am not an expert in the French revolution, and I know nothing about Adachi’s original book, but I get the general impression that Sakamoto’s manga is a creative account; not quite Riyoko Ikeda’s fanciful Versailles, but nonetheless of the imaginary France that has long been a fixation for Japanese pop culture. Certainly Sakamoto’s decision to depict Sanson as a lithe, androgynous twink straight out of Castlevania: Symphony of the Night is very creative and pleasant. This first volume charts Sanson’s reluctant embrace of the role he was born into despite his frail constitution and moral/spiritual objections: publicly cutting people’s heads off with a sword on behalf of the crown.

Sanson hates all this killing. It contradicts the will of God. It is not beautiful. It’s public and frightful. He’s a soft, weak lad. He cries about it. However, he is broken into the task at the hands of his father’s relentlessly cruel and elaborate staged beatings - which, incidentally, force a powerful erection out of meek Charles-Henri. Sakamoto dutifully depicts this surge in about as much detail as a mainstream Japanese publication permits. Weeping in private while embracing a cold, stoic demeanor in public, Sanson learns his abominable craft, the art of beheading, with the eyes of common people observing his every gesture at each execution. His interiority shorn away, a celebrity, young Sanson is esteemed by his ability to deal death. Skilled, swift beheadings are judged the work of a merciful angel of death. Careless, inexperienced movements driven by emotions are shameful violence, the work of a brute.

Sanson buries his personhood, his mortified sorrow, beneath his corporal work, his bloody inheritance, while quietly encountering transgressions against the aristocracy which molded him. Whenever the possibility of rebellion opens for Sanson, it is just as quickly shut by his duty. He has a brief homosexual encounter with a count’s son, only to be reunited with the beautiful young man beaten and in chains, waiting for his beheading. Sanson takes pity on a poor, starving father caring for his sickly, dying son, forging a friendship that exposes Sanson to the wretched living conditions of common folk across the French countryside. The two are reunited as Sanson witnesses his friend subjected to extreme torture, waiting to be drawn and quartered under his guidance.

This intensely eroticized web of repression, longing and politics is all very Catholic, and all very Mishima - I could not help but note visual allusions to the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian. Correlations between killing and sex are quite explicit; eager attempts by Sanson's father to blot out the inadequate bastard by producing a new heir provide the comic’s more vanilla scenes of erotic intrigue. Sanson is always fighting to contain his emotions and do his job well, because when he is seduced into showing his anger, his movements become clumsy. If a single stroke fails, it becomes the beating of a still-breathing body into a bloody pulp. He’s hiding his sorrow, but other feelings are hidden as well, like the arousal his young body betrayed under torture. Killing is exciting, after all. Isn’t this a little sexy? Briefly (for now), Charles-Henri’s sister, Marie-Joseph, emerges as a counterpart to the reluctant executioner, a young woman possessed of a scientific zeal for dissection and dismemberment: the study of corpses and the many creative methods to produce them from living people and animals. Her thirst for blood and viscera cannot be slaked while the social order still stands, because the job poor Charles-Henri was unwillingly born into is only given to male heirs. If eager women were to voluntarily take on the fun which sad, reluctant men carry out by duty, God only knows what chaos would unfold.

Innocent is lurid entertainment with a bit of depth and a lot of sensation, albeit within cable TV bounds. Sakamoto’s art is attractive, a pastiche of Kentarō Miura with an eye for viscera, historical atmosphere and beautiful effeminate men that make everyone else look very ugly. However, there were times I wanted more; panel layouts are stiff, pages full of yawning blank gutters broken up occasionally by splashes. There is a rigid precision to how spaces are composed, with impersonal linework and smooth computer screentones that put the spectacular allure of the pictures at a distance, as if under museum glass. I hope Innocent will go further and allow itself to be drawn in more fully by its own glamor, but perhaps when showing executions to a mass audience like the readers of Young Jump, a little restraint is necessary.