“You can’t teach genius,” my friend and colleague Glenn Bray quipped in a recent email exchange. As an after-school teacher of comics, cartooning, and storytelling, I must bow my head and agree. One out of 50 of the middle-school kids I teach has the bonafide comics bug—that burning desire to draw and tell sequential stories. The rest do their imitation Sonic the Hedgehogs, Wimpy Kids, and Bendys, despite my invitations to create new characters instead of expending their energy on fanfic.

Some of the subtleties of How to Read Nancy—and its wry humor—may be lost on the age-group I teach, but this book has the potential to inform and inspire, by example, the process of comics-making to anyone willing to lend an ear and focus. It’s the best thing to happen for comics in a long time.

To make comics, one must study comics—just as a filmmaker watches movies and a novelist reads other writers. No art exists in a vacuum. We get the occasional void-artist (Henry Darger, Fletcher Hanks, Rory Hayes) but they’re a rare exception. With its focus on the most mainstream cartoonist of the 20th century, authors/theorists Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden expose the self-evident truths hidden in plain sight in three panels of a comic strip that came and went in a blip in the summer of 1959.

This handsome book, published in a softcover/hardcover hybrid like Fantagraphics’ three volumes of Nancy comic strip reprints, begins with a well-researched, engagingly told biography of Ernie Bushmiller, the creator of Nancy (itself an offshoot of Fritzi Ritz, a strip Bushmiller inherited from a colleague in the mid-1920s).

Bushmiller’s is a classic American rags-to-riches story—a wistful reminder of that once-viable possibility to rise above your raisin’, as the folk saying goes. Bushmiller has been a cipher in comics history—a casualty of the anti-Nancy bias that reduced him to the ilk of a Jim Davis or Scott Adams. His story echoes many early 20th century cartoonists’—humble beginnings, a slow journeyman career as newspaper artist (Bushmiller drew crossword puzzles as part of his duties), a series of failed newspaper strip ideas, and the breakthrough which slowly built to national success by the 1950s.

The biography, which fills pp. 21-70, is loaded with images and artifacts that support and enhance the story of Nancy’s creator. This section of the book stands alone, and is a compact font of information that gives the reader a greater grasp of Ernie Bushmiller’s work. You see him go from amateurish tyro to a mastery of cartooning’s skillsets, which the artist elides as his success grows.

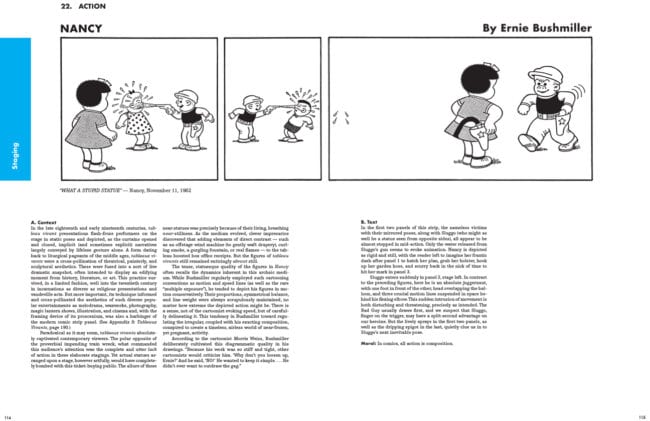

By the time of the August 8, 1959 strip that consumes the middle third of the book, Bushmiller’s cartooning is stripped bare of distractions and decoration. At first, the notion of spending 80 pages deconstructing it seems a lark: what isn’t already evident here? The WYSIWYG approach of Nancy appears bullet-proof. Karasik and Newgarden prove that still waters run deep.

Art Spiegelman is fond of showing a page from Batman #30, published in 1945 and reprinted in the 1980s hardcover The Greatest Golden Age Stories Ever Told, as an exquisite example of what NOT to do in comics. The page, with its confusing layout, traffic arrows, and awkward empty space, is the dark cousin of the 8/8/59 Nancy, and merits inclusion here:

Much can be taught—and learned—about how NOT to do comics with this page. I have sprung this page on my students, without context, and seen confusion, disbelief, and disdain play over their faces as they struggle to parse it out. The Batman page ties your eyes in knots. The Nancy strip glides across them like drops of Visine. It resists the reader’s investigation—a stronger reason to dig deeper.

In 44 spreads, every aspect of this three-panel strip is autopsied. Some examinations are whimsical; some reach powerful conclusions. Each spread examines one facet of what makes comics comics, and what compels us to read, study and create them. This section ends with an inspiring, stirring summation, which I’ll quote in part:

Comics are very much with us today, very much alive and kicking…comics will persist. There were lousy comics in 1959, there are lousy comics today, and, needless to say, there will be more lousy comics in the future … but there will be plenty of good comics, too.

After this moment of reflection, How to Read Nancy moves on to a robust set of appendices that support and expand the theses of the 44 autopsy chapters. After seeing the 8/8/59 strip until its panels and borders are burned into the reader’s retina, the appendices offer a refreshing bustle of images, many in color, as they explore the origins of the gag we’ve spent so much time taking apart (and which involves an all-star global cast of early cartoonists). Also explored are the perils of comics reproduction and formatting, fine art’s mischievous dance with comics, Nancy’s alternate universe career in comic books (which involves John Stanley) and some fascinating examples of unpublished/unfinished Bushmiller strips.

This section is as informative as the 44 theses, and fills the reader’s head and heart with the possibilities evident in the comics form. This, likely, will be the most revisited area of How to Read Nancy for many, with its wide array of images and sidebars.

Students, there is a recess period in this book: 42 pages of prime-period Nancys, printed four to a page and grouped by theme—another reduction of a prior format (Kitchen Sink Books’ topical Bushmiller tomes of the 1980s). These, combined with the earlier and later Nancy strips scattered through the book, may make a new Bushmiller fan out of more stoic non-believers.

Ernie Bushmiller, like filmmakers Jacques Tati, Tex Avery and Frank Tashlin, was a master diviner of humor from anything around him. The mechanics of what make us laugh also apply to what scares us, what chokes us up and what causes us to think and question.

Karasik and Newgarden show us the tools and make suggestions, but leave their ultimate use and appreciation to us. Comics have been made by assembly line—Bushmiller worked that way, in one of the book’s revelations—but their creation is most often a solitary task, born of reflection. With these tools laid out neatly and intelligently, comics makers have available a world of inspiration and challenge within the pages of How to Read Nancy.