The sports bra stays on during sex. Breasts are bound and untouched while the ass gets dildo-fucked, so when Ingken, in the post-coital afterglow, tells their girlfriend Lily “I don’t really think I’m a woman,” you might believe the response of “I’ve never seen you as a woman.” You might also believe Ingken when she acts untroubled by Lily’s pursuit of a woman she says Ingken would really like. These characters regularly offer affirmations to each other of the “yeah I know” variety - meant to indicate an understanding so deep that things don’t need to be spoken, but slowly shutting down communication over time. A reader must look past the blandly-supportive words being said to see the desire for silence lurking just below the surface. They need to look past the superficial banality where so many comics exist to see that they are reading a work with actual depth. For everything that the characters in firebugs don’t have to say to each other because they know each other so well, there is more that a reader has to infer: there is a great deal that they are not talking about. The current vogue for comics to contain a minimal amount of words on a page means much must go unspoken, but here the spare use of language speaks to a set of unarticulated ambivalences regarding a complex situation, rather than a simplistic authorial perspective. Ingken seems too depressed to articulate their desires, while Lily says supportive things seemingly learned from the sort of self-help guides that get purchased for teenagers by well-meaning liberal relatives.

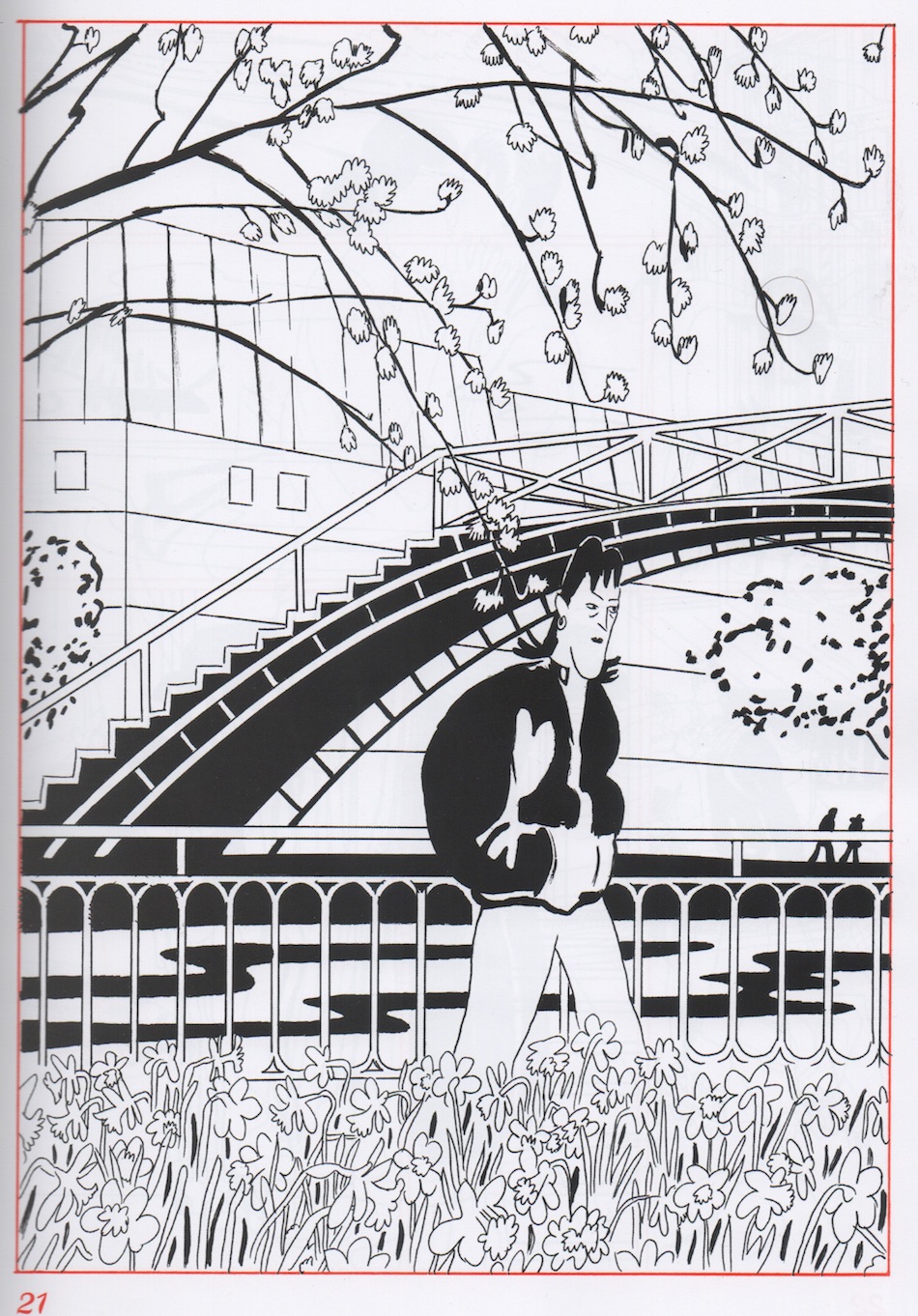

When prodded to come up with a more masculine name, Ingken suggests Henri might be one they’d be comfortable with, before immediately retracting the idea. I see a lot of Henri Matisse in Nino Bulling’s brushwork, and from Ingken’s utterance I detected a parallel between their reticence to socially transition and the artist’s hesitation in owning up to such a canonized influence. I will say the author achieves something they might be uncomfortable admitting as an aspiration: they depict a young queer Europe as if Matisse drew chunky sneakers. The textures are variegated, but the brushstrokes are unerringly graceful. The faces avoid being traditional beautiful, which I took as a deliberate choice. Beauty is assigned to the realm of the feminine, and where there is beauty outside the binary, it is non-normative, defined on its own terms, for those with eyes to see. Landscapes, flora, the drapery of clothes, the sheen of hair, the shape of molten candlewax: all of these are understood as beautiful, and Bulling captures them well. The human figure is rendered with a similar approach, rather than designed with an eye towards remaining on-model. The compositions on the whole have enough depth that moments of stillness can be sat with, so that the reader can contemplate what the figures within them are feeling and why.

The book is published without a spine, paper stock varying throughout, with glossy stock on the back cover and uncoated paper on the front. These shifts feels largely arbitrary to me, and likely make the book a more delicate object, but it feels nice in the hand, and the book can lay flat. Red thread stitches the signature, visible at the book’s binding: the same hue that’s printed as the book’s second color. The use of red is limited to panel borders, lettering and sound effects, flames, and the trails insects make through the air. On a certain level, this second color can be viewed as providing very little - the flavor of something so subtle it might as well not be there at all. And yet it is there, just in small quantities: this speaks to artist’s restraint. In calling attention to how the book is bound, we can see this restraint as binderlike, in the sense of a chestbinder for transmasculine people, which Ingken’s sports bra stands in for. To take it a step further, the absence of a bulging spine allows the physical object to luxuriate in the freedom of flatness, though to be aware of the nontraditional aspect of it calls attention to the book’s physical vulnerability.

The characters in firebugs are not arsonists, and the only fires that rage out of control within its pages are those glimpsed on a web browser. Fire is a metaphor, but one each character has to divine the meaning of for themselves. Is fire a place of rebirth, as in imagery of the mythological phoenix, or is it purely destructive? Lily, a dancer and performance artist, suggests the former, while Ingken, a doomscroller of news footage of desolation wrought by wildfires, is inclined to believe the latter. This is a place where differences of age play a part: on a long enough timescale, the decimation of an ecosystem will eventually give way to a new biome. Looked at from the perspective of the present, upheaval merely eradicates what was there before. The older one gets, the less one has time to waste waiting for new blossoms to rise from ash. There is an age difference between where Ingken is at at the time the story takes place and where Lily transitioned in the time before the book began that defines the difference in their perspectives.

The specifics of age add a good deal to the book’s contents, if one has the life experience to infer the meanings of what it is to be one age and not another. Identity, for a person in their 30s, is not simply a question of category or pronoun, but an adulthood’s worth of job prospects and relationship statuses one is loath to abandon in the name of growth. I’ve read recent comics about queer relationships where age is elided entirely, in favor of the presentation of a general romanticized youth. Such a portrayal may feel true to the shared feeling of commonality within a large social circle of casual acquaintances, where an egalitarian assumption is filled out with projection of shared similarities, but constructing fiction that posits characters as being at the same place in their mental and emotional development makes for work that feels distinctly simplistic. firebugs is a relationship drama where characters are realized as individuals, and it’s a stronger comic than one that merely parades the fashionable before the reader.

Climate change forms the backdrop of the story, but it's only about that subject inasmuch as these characters act towards the slow motion collapse of their relationship the way we all must act about the collapse of our world: pretending as if it’s not happening, the best we know how. Neither Lily nor Ingken (nor Anya, the woman Lily dates on the side) is any more culpable in the relationship’s failure, the same way any non-billionaire is particularly culpable in our ongoing ecocide. There can be no resistance - only going along with gradually-worsening conditions, like the lack of a partner’s sexual desire, as if it was something one should’ve seen coming. What else can one do, given the circumstances? As the book goes on, there is a sense that Lily is doing what she is supposed to, being as kind and supportive as she can be, because she has completely checked out of the relationship and is now aiming towards ending things as peacefully as possible.

Lily breaks up with Ingken near the end of the book, and shortly after, Ingken meets someone new. This could be a good thing, an opportunity for a new romance, but carried within that is the idea that a new self could be presented to this new person: a new name can be given, when asked for a name. A new relationship necessitates new communication, and with it an end to elision in deference to the unspoken. It is implicit that the conclusion of the comic carries with it the need for a new language that might be beyond the formal system by which the comic is bound: in the place of images and their quiet, there will be talking, in great quantities.