“Rainbow Capitalism” is one of those quippy neologisms I find to be equal parts necessary and bothersome in online discourse. Come Pride season every year I see a lot of my fellow queer people online bringing out this term to describe corporate efforts to turn Pride into a marketing tool, in what comes across as shallow and pandering to some and infuriatingly disingenuous to others. Usually I find myself in the latter camp, having grown up in a particularly conservative environment during the early 2000s, a time caught in the crossroads of the open homophobia of the late 20th century and the present day - which, while better in many ways, feels like it’s stumbling its way backwards more and more on the daily. All of that doesn’t stop me from growing somewhat dissatisfied with the way some of these criticisms get reduced to easily spread soundbites with little thought put behind them; and this put me in a really weird spot when reading this year’s DC Pride book.

For the second time in as many years, DC has put out a 100+ page anthology to celebrate Pride month, showcasing stories centered around their cast of LGBTQ characters. Though the book is titled DC Pride, the Pride branding and banner have been used in multiple ongoing books since last year, making the anthology proper a showcase of sorts to celebrate the occasion. Reception, just like last year, has been mixed; some outlets have praised both the existence of the book and a few of the stories individually, while others have heavily criticized its overall quality. It doesn’t help that, like last year, the book has fallen victim to the out-of-context-panel-going-viral-on-social-media curse, further souring perception among more cynical readers, with many taking it as confirmation of the book’s marketing bend. Reading it now, I find myself somewhat caught between both of these positions - and I’ve had a horrible time trying to articulate why, exactly (which is half the reason I’m writing this at the end of June).

Speaking in terms of writing quality and nothing else, I found that the really good stories in this compilation are better than last year’s, but some of the weaker ones really bring the book down much more noticeably. One issue I noticed in the majority of the book is how much page space is dedicated to internal monologue with the backdrop of some manner of (mostly) thematically-appropriate conflict. Not to fall victim to soundbite-criticism myself, but there’s a whole lot more telling than showing throughout, which only really works with stories like these if there’s a perceived sense of sincerity - and only a few of these really felt like they had it. Part of the problem seems to be that there are so many individual stories in the book—12 in total—that very few of them have the page count to breathe. They all feel rushed to fit in, like most of the stories are less actual narratives than diary entries pasted onto artwork of an unrelated story until the last few panels (and, in at least a couple cases, not even that).

Several of the stories in the book come across as thinly-veiled previews for other ongoing series, something which many people scoff at, though I don’t necessarily see that as a bad thing. Full disclosure: I haven’t kept up with DC in about 10 or so years. I stopped paying attention after they rebooted away nearly every character with which I had a passing interest, and though I tried to come back after the Rebirth relaunch-of-sorts in 2016, I wasn’t able to get into anything. By that point I had already fully changed my reading habits to web-based comics and manga as opposed to anything in print from the Big Two. So as someone who grew up with DC, later fell off their books, and being a queer person myself, it feels like I’m exactly the target audience for a showcase of the company’s LGBTQ roster of characters - and because of this, I would frankly not be too offended if every story in the book followed up on an ongoing series or connected back to a book collection I could pick up. But the multitude of stories in DC Pride where basically nothing of consequence happens had the complete opposite effect on me. If DC is so invested in trying to use Pride to sell me more books, then this collection almost makes it feel as though the company doesn’t have enough queer representation to fill the pages of their ongoing series with stories I would like to continue reading.

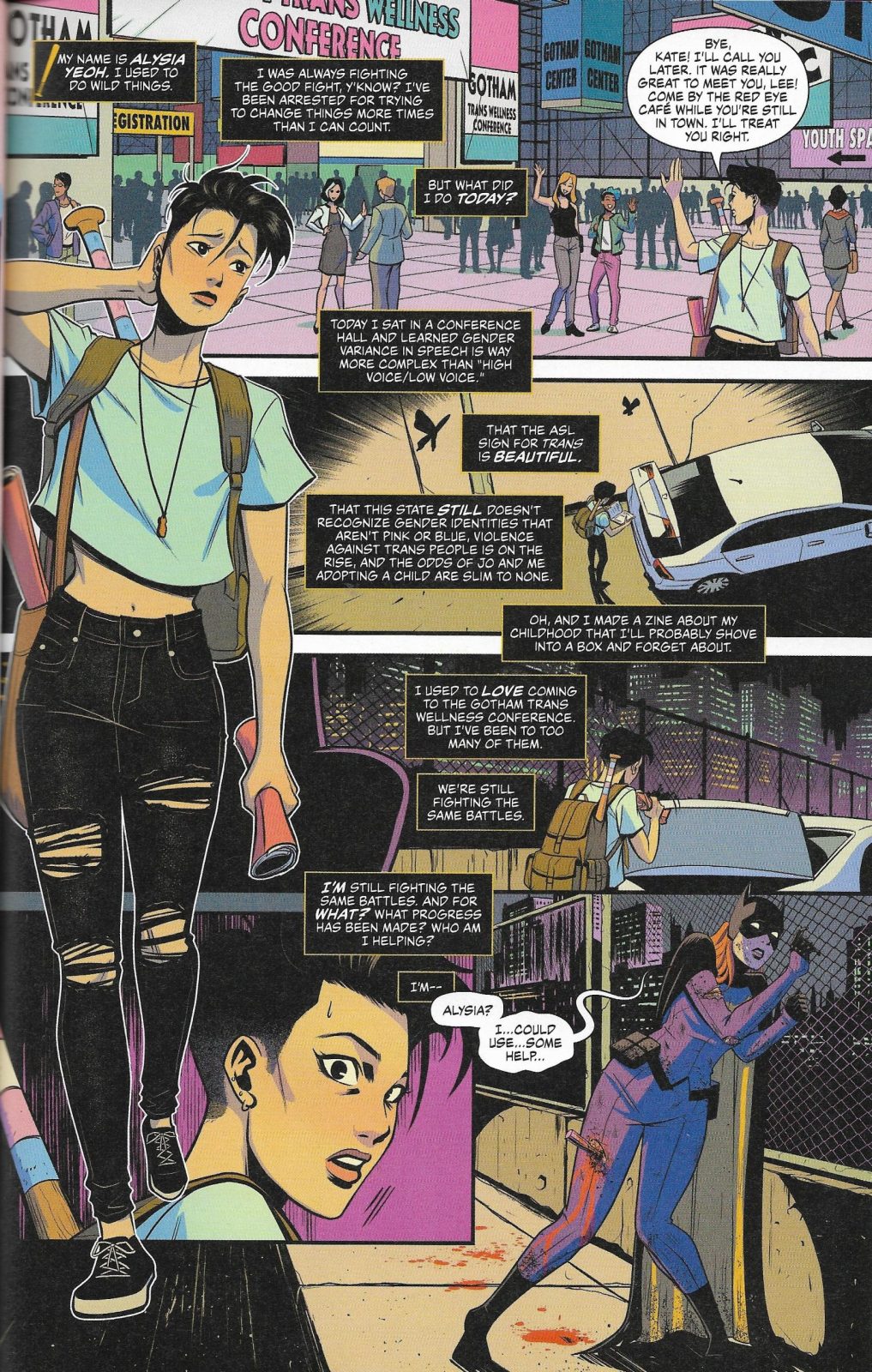

At its core, I feel like this is my main problem with DC Pride; you can’t have it both ways, with half a book that’s using the celebration to try and sell me more books, and half a book that’s trying to show intimate, personal narratives about identity that might resonate with readers. There are some genuinely good, touching bits of character writing here, such as the short story in which Connor Hawke (Green Arrow, it’s a long story) writes a letter to his mother trying to explain what it means for him to be asexual - a label far too often excluded from LGBTQ spaces, often times intentionally so. I also feel like I’m in the minority of people who actually enjoyed the Batgirl story featuring trans supporting character Alysia Yeoh finally getting to put on a costume and fight a named villain, while narrating a somewhat ham-fisted but nonetheless refreshing reflection on fighting the same battles over and over again in trans activism.

But for each of those, there’s also stories like a Harley Quinn/Poison Ivy short that has basically no plot to speak of, a Robin (Tim Drake, that is) story that doesn’t amount to much more than him being late for a date, or a story about Superman (that is, Jon Kent, not his father Clark, the Superman that most people will be familiar with) inviting Robin (Damian Wayne, not the aforementioned Tim Drake) to a Pride celebration in Metropolis which includes the now-infamous gag about the latter bringing crowd control and riot suppression weapons to the event under the justification that “Pride was originally a riot,” which reads as particularly tone-deaf in this day and age, yet not outrageous enough to circle back to being actually funny.

It’s that opening story which had me struggling the most to articulate how I felt about this book. On the one hand, I have to recognize the sheer significance of a cultural icon such as Superman being gay - and, marketing gimmick or not, it’s still a major risk to commit to highlighting that fact in a year that has seen the fastest rise in violent homophobic rhetoric in the mainstream and within comics circles that I have seen in my short life. This is both true for this book, which opens with his story, and the ongoing Superman: Son of Kal-El series, which has come under flak constantly since this development.

On the other hand, the cynical part of me has to remember that “Superman is now gay” comes with its own series of qualifiers; it’s more accurate to say that the third person to hold the title of Superman in the last decade—who is not the one everyone knows, but his son, introduced roughly five years ago—is now gay in a spinoff book. Suddenly I’m reminded that, like everything in comics, this too shall pass. At some point, the status quo has to be restored, and this is a much less meaningful development than it’d appear to be on the surface - it gives me flashbacks to a few years ago, reading headlines claiming that DC had “revealed” Green Lantern to be gay, which meant they had revealed a less-popular incarnation of the character to be gay in a parallel universe (though this change did eventually make its way back to regular continuity).

On the other other hand, however, I have to wonder if there are any young, queer comic fans who will read this and not see any of the qualifiers I see due to my age and experience with the medium. I have to wonder if there is a gay teen out there who sees himself in this Asterisked Superman and gets a bit of joy from it. I can’t help but hope that this hypothetical boy will read the lines “I see you, [...] I am you,” and feel a little less alone, a little less scared, because he finally sees himself in not just a cultural icon, but the symbolic face of comics as a medium in the mainstream. I can’t help but wonder if I could’ve been that person with any of the other characters in this or last year’s anthology back when I was a scared, closeted queer teenager and young adult without any kind of support network, constantly feeling like I was completely alone in the world and that I wouldn’t get to live past 30 (I’ll get back to you all on that part in a couple more years).

The book closes with "Finding Batman", an autobiographical story written by Kevin Conroy, the voice of Batman for people of my generation onwards, in which he discusses the difficulties he had being a gay actor in the '70s and '80s before landing the lead role in Batman: The Animated Series: what it meant to him, and how he could see himself in the character - how finding Batman let him find himself and come to terms with much of the suffering he endured throughout his life. It’s a story that queer people of my generation will have already heard, no doubt: friends dying of AIDS; the casual homophobia expressed even by those sympathetic to us; the feeling of isolation from friends, family, and society as a whole; the closing of doors and the resilience necessary to simply exist in a world that constantly reminds you how much you don’t belong.

Stories like this are often brushed off by critics, since many of us have heard them time and time again, to the point where some lament that they are the only stories we seem to be allowed to tell; yet they still remain a potent reminder for people my age and younger of the suffering endured by the generations that came before us. "Finding Batman" feels particularly poignant because of how close it will come to fans of the medium who also saw themselves in the characters they read or saw. And, as much as I understand that there is nothing here that hasn’t been told with more nuance or greater strength in other media, what’s important is that it is here; that the story is being put out by one of the two biggest publishers in superhero comics, and that it’s attached to perhaps their most popular character, in both name and symbol.

While I am a strong proponent that good queer art isn’t found in the mainstream but written by independents, and often goes formally unpublished, I finished this story reminded of the role that the dreaded Mainstream Superhero Comic Book can have thanks to its arguably niche appeal relative to its cultural footprint. Comics, at the end of the day, are still the domain of comics enthusiasts, no matter how much the medium’s influence seeps into the cultural mainstream. Perhaps there is a place for queer creators in this industry to tell their own stories with more freedom than they otherwise could in a bigger medium. Perhaps the perceived silliness of the form can lend to its applicability and broaden the appeal of queer narratives beyond LGBTQ circles without distilling them for general audiences. What better medium than comics, superhero or not, for us to get our stories out there even by proxy, given its history of being shunned until it was commercially viable; even if the result is ultimately messy, rushed or just plain weird.

And as I am thinking this, I begin to consider Dark Crisis, the event DC has running at the same time as its DC Pride titles, and I remember that, ultimately, I am being sold a product with the explicit purpose of selling more products, and I am back to the drawing board. Whatever merits I find in this book are complicated by that specter called Rainbow Capitalism, making it difficult to pinpoint how I feel about DC Pride. No matter how much I might see myself in some of these stories, this is still a corporate endeavor aimed at making me give them my money and continue giving them more of my money, and that I only see stories told by people like me because it is a commercially safe investment to appeal to us. A touching confessional about the difficulties of being gay in the entertainment industry from one of its most recognizable voices is coupled with featherweight stories featuring characters I am encouraged to follow into a dozen-or-so-title event about how the Justice League is dead. Happy Pride, everybody. I’m still going to buy this next year.

* * *

Cover art by Jen Bartel.