Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant? is Roz Chast's first memoir, but I've always scoped a deep autobiographical undercurrent in her cartooning. The characters she's drawn for The New Yorker since 1978 (eventually becoming the magazine's star cartoonist), have aged in much the same way that Chast, her parents, and later her own four-person family unit have matured in her drawings – not in a Gasoline Alley sort of way, but in general.

Now Chast has snuck up on her own childhood by way of dealing with parents George and Elizabeth's extended sunset years and eventual deaths in 2007 and 2009, respectively. It's not a pretty story, none of it, and Chast draws on obviously untapped oceans of guilt, anger, and sadness in order to recount the story of a family she never felt quite part of.

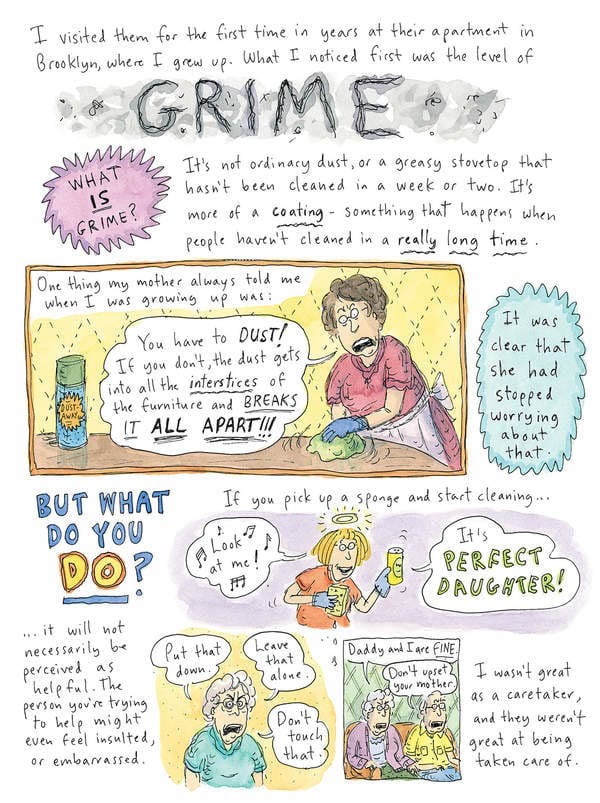

It begins portentously on September 9, 2001, when Roz decides to visit her parents in Brooklyn for the first time in a decade. The overly protected only child of relatively old parents born ten days apart in 1912, Roz begins to make more frequent visits and starts helping them plan their endgame. When Elizabeth falls from a stepstool in 2005, echoing a much earlier tumble that caused the death of what would have been their first child, the dire legal, financial, and psychological complexities of death in America are set into motion.

Like much of Chast's work, Can't We Talk is a formal triumph that at first glance looks somewhat a mess. The New Yorker's most stylistically experimental cartoonist, Chast draws single-panel cartoons and multipage nonfiction narratives for the magazine in addition to creating monumental lists, typologies, calendars, archaeologies, fake publications, and real children’s books. Chast rarely makes do with a single gag. Her cartoons are often mini-multiples. From the rocky collection of "little things" ("chent," spak," "kabe," etc.) that comprised her first TNY cartoon, she has been the magazine's preeminent underpromiser/overdeliverer. She also happens to be one of the magazine's best writers, and the book gives her the space to expand on funny, anxious, and often infuriating things that happen in her cartoons when she wants to convey the full weight of the Chast clan's considerable neurotic karma.

Chast masterfully sketches the extremely close passive- (George) aggressive (Elizabeth) dynamic of these two former public-school teachers and administrators. "My father chain-worried the way others might chain-smoke," she writes, illustrating the complex with a "wheel of DOOM" (water in ear, choking, etc.) surround by "cautionary" tales from her childhood in which a lump, rash, or headache led to a quick, unexpected death. Her mother, on the other hand, is a critical, controlling woman always ready to deliver a "blast of Chast."

As George slips into dementia, Roz moves her parents from Brooklyn to a managed-care facility near her home in Connecticut. The logistics seem staggering, although perfectly normal for a nation that doesn't give a rat's ass about death with dignity. And although Roz barely alludes to either her career or own husband and children, you sense the pressure building. She eventually brings her "old-country grandmas" into the picture as she begins collecting Elizabeth's fractured, end-days recollections and fantasies.

As George slips into dementia, Roz moves her parents from Brooklyn to a managed-care facility near her home in Connecticut. The logistics seem staggering, although perfectly normal for a nation that doesn't give a rat's ass about death with dignity. And although Roz barely alludes to either her career or own husband and children, you sense the pressure building. She eventually brings her "old-country grandmas" into the picture as she begins collecting Elizabeth's fractured, end-days recollections and fantasies.

A full-page drawing of foreshortened George's despairing relief upon Elizabeth's return from the hospital after the fall is shocking in its vulnerability. But the book's most powerful images could well be the family photographs in which Roz displays visceral discomfort around the parental dyad. Photographs of her parents' glumly accumulated possessions are almost as depressing. But Roz dignifies Elizabeth's passing with a series of sickbed drawings accomplished during the final days she spent in silence by her side.

Roz Chast's story is both unique and typical, a spectrum already suggested by her eccentric-everyperson art. Death is often a relief, and Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant? is a big heaving sigh of a book. George and Elizabeth, meanwhile, or at least their cremains, currently reside side-by-side inside plastic bags inside black plastic boxes inside white cardboard boxes inside velvet bags inside a Channel 13 tote bag (George) and "maroon velvet drawstring" bag (Elizabeth) inside Roz's bedroom closet.

Richard Gehr's I Only Read It for the Cartoons: The New Yorker's Most Brilliantly Twisted Cartoonists, will be published by New Harvest in October.