This is the latest in Tom Pomplun's increasingly ambitious line of comics adaptations of public-domain prose works. This volume, which adapts classics from African-American writers and poets, is unusual in that he shares editorial duties with frequent series contributor Lance Tooks. Every contributing artist and writer to this volume is African-American, and the results are fascinating. As always, Pomplun's focus is on works in the public domain, and this volume zeroes in on writers central to the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. It's an terrific mix of voices, ranging from highly refined language to dialect. There's a mix of serious and comedic, pointedly sociopolitical and fantastical.

More so than the other volumes of this series, African-American Classics feels like a primer. The tight historical focus and the fact that the writers are chronicling a specific kind of struggle make it highly illuminating of both time and place, but the editors also find ways to connect the works to more modern times. Obviously, the choice of artists and writers is part of that, but some of the more pointedly political pieces still bear relevance to today's society. This volume also leans a bit more heavily on poetry than past volumes, which makes sense given the wider focus the subject lends itself to (as opposed to past volumes like Western Classics, Science-Fiction Classics, etc.)

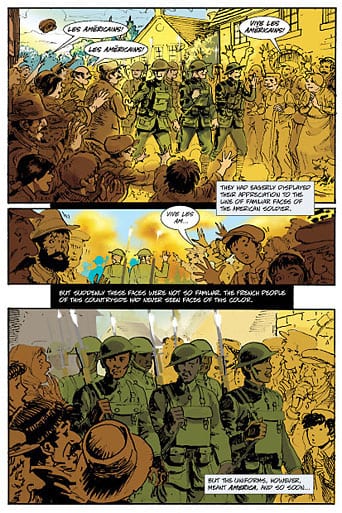

Illustrated poems tend to leave me cold as a comics reader, but the graphic focus of the Langston Hughes poems "The Negro" and "Danse Africaine" (painted by Stan Shaw and Afua Richardson, respectively) connects them to the feel of the text without overwhelming it. That said, the true highlights of the book are the short stories. Alex Simmons does a sturdy adaptation of Florence Lewis Bentley's "Two Americans", a story about a black soldier who saves a white soldier on the field, even after realizing that the white soldier had helped to lynch his brother. The rawness of the story's emotions are well-captured by the distinctive pallet of Trevor Von Eeden, whose shifts from mustard yellow to deep purple to blood red to an ethereal green masterfully manipulate emotional reactions as the story unfolds. In the denouement, he softens both his line and his color scheme to reflect the deeper understanding that's been reached.

Another highlight is Kyle Baker's "On Being Crazy", written by W.E.B. DuBois and adapted by Pomplun. DuBois's scorching satire of an educated African-American man being confronted by racism left and right is hilarious, as the protagonist answers each injustice with a clever bon mot. Baker is the right man for this job, given that his art is somewhere between stylized and naturalistic. Another solid story by a mainstream veteran is Christopher Priest's adaptation of Robert W. Bagnall's Lex Talionis, drawn by Jim Webb. It's a brutal, clever science-fiction story about an African-American chemist who gains revenge against the white man who murdered his sister. Even though the narrative style gives away the ending, it's a gripping enough story not to matter. Instead, it's the emotional content of the story that's key.

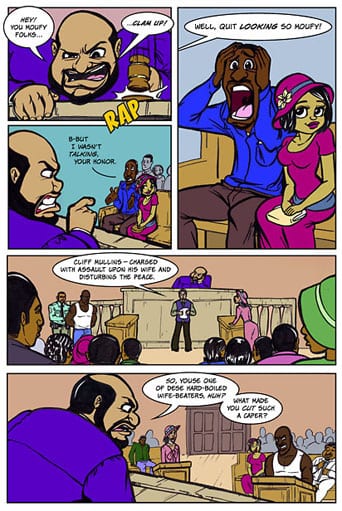

The funniest stories in the book are "Lawing and Jawing" and "Filling Station", both by Zora Neale Hurston. They're both written in dialect (which made them controversial for quite some time), but they're both razor-sharp in tone, witty and knowing. (Sample: when a judge character asks a woman if she was cut in the fracas, she replies, "Not in de fracas judge--just below it.") Pomplun and Arie Monroe adapted the first story, and Monroe's cartoony style fit the tone of the narrative snugly. "Filling Station", drawn by the great Milton Knight, is an example of two men "playing the dozens" as they insult each other's home states (and brands of car), right after two men vie for the affection of a woman. Knight's rubbery line and deep hues blend well with Hurston's style of exaggeration.

Pomplun really spares no expense with regard to production values, and the use of color is absolutely essential to the success of many of these stories. The Von Eeden story, for example, would not have nearly the same impact without his displayed range of the palate. Since the series went to full color in Science Fiction Classics, the next several volumes have seen a decided upswing in overall quality. Part of that, I think, stems from Pomplun perfecting the process in which he figured out what stories to adapt and what artists to choose for the job. It also didn't hurt to have Tooks, himself an artist, as a true co-contributor. That graphic understanding of story had to have made a difference in the overall visual impact of the book.