Upon publishing the interview with Leaping Windows Comics Café, I was informed by an elder Indian that rental bookstores – locally called “circulating libraries” – are not uncommon in Mumbai. There used to be more, I was told, but there are still some out in the suburbs, though they deal mainly in books in Hindi and Marathi (the local language) rather than in English.

Online searching turned up more than a dozen scattered across Greater Mumbai, some of which are actually in the heart of the city, near railway stations and major intersections. These latter seem to be mainly older businesses, hanging on since the 1950s and 60s. I am also told that, out in the suburbs, a number of “paper marts” – paper recycling shops – have begun doubling as lending libraries, redirecting not only junk books and magazines that come their way, but also cartons of cheap remainder books. I have heard – though I haven’t seen them – that there are book vans that show up in certain neighborhoods once every three days or so, with blinking LED lights and megaphones tootling jingles.

All of which is to say: borrowing books for a fee, beyond the familiar institutions of private and municipal libraries, is neither a new nor rare thing in Mumbai.

One of the older establishments is Victoria Music House & Library in Mahim, named (like Victoria Dry Cleaners next door) after Our Lady of Victoria Church down the street. Founded in 1950, the library is today run by one Arif Merchant, whose name sounds like a character from one of those dry-wit, Indian magical realist novels. Last names in India are fairly reliable and easily legible indicators of one’s family background: where you came from, what caste you belong to, what your parents do for a living. Within some communities, the name itself is the occupation. For example, I have a Parsi friend named Reehan Engineer. His grandfather was a Mistry, who then renamed himself to reflect his occupation: as an engineer. My friend, however, is an artist and actor; an engineer of words and gestures and pictures? With increased migration and greater social mobility in the past half-century, a last name expresses more a parent or grandparent’s life than one’s own situation in the present tense. But in a case like that of Mr. Merchant of the Victoria Library, a business founded by his grandfather, the name still describes the man.

Victoria Library is a relatively tidy affair with books stacked thirty volumes high by category and shape. The bulk of stock sleeps on bookshelves behind these towers, with a horde of comics snoring heavily in a back corner. There lay mainly Amar Chitra Katha, Tinkle, Archie, the British romance comics Star, and the British romance photo novel magazine Blue Jeans. Mr. Merchant’s father, it turns out, is an avid comic book collector, owning, by his estimate, some two-three thousand items, mostly Marvel and DC superhero comics. “Indian comics are no good,” he says. His collection has ebbed and flowed with the lending library business, with duplicate copies sold or rented out through the store, and missing issues obtained through locals looking to make a little money by cleaning out a shelf of old books and magazines. Clearly Tinkle, Archie, and Star are unpopular with the collector and library reader alike, for it required a move of furniture and an open-handed whomp whomp upon the books to clear the dust and simply get a look at what they had in stock.

In contrast, the entry area of Victoria, where Mr. Merchant sits, is bright and shiny. Maybe the word is “tinselly.” Imagine taking a flash photograph in a room with lots of glass and reflective surfaces, illuminated by soft blue fluorescence. Now imagine that flash photograph a physical space, the sharply reflected streaks of light caught in the picture now a permanent feature of the room. That is the feel Victoria has, wall-to-wall with vinyl-covered books, plastic-bagged magazines, and encased DVDs. Though the DVDs occupy less than a twentieth of the space that print does, they essentially carry the store economically. A number of circulating libraries have gone this way entirely, having converted into movie rental shops with only some books lingering on. With pirate movies so widely available on the street and online, I imagine this is tight, and ever-tightening, business.

As for the stores that refused to go A/V, one presumes they simply vanished. But recently I happened upon a lending library in south Bombay – the Rita Circulating Library – that has survived despite a narrow commitment to paper. For those who know the city, it is just west of Metro Cinema, before you get to Gol Masjid, the round mosque that divides the street in two. It is situated in a cubbyhole to the right of Hotel Fortune, on the north side of the street. Its address is 32 Anandilal Podar Marg, also known as Marine Street. The neighborhood is officially Marine Lines, though everyone I’ve asked calls the area Metro, after the movie theatre. Despite having walked down this stretch at least a dozen times in the past year, I might be forgiven for previously overlooking Rita, for the shop is about three feet wide and five feet deep, the kind of pocket space usually occupied by cigarette, paan, or phone topping-up vendors. Rita’s most important dimension is its third: the ten feet up to the ceiling, making room for more bookshelves and more books.

The store is run by the 80-year-old Abdullah Amir. He lives across town in Mazagaon, a Muslim neighborhood in east-central Mumbai. Every time I have met Amir, he has been wearing an identical outfit: a white kurta pyjama and a white skullcap. His beard is impeccably trimmed, and should be white, but is tinged yellow-orange at the edges with henna. Victoria’s Mr. Merchant is also Muslim, a Khoja Muslim, though I assumed from his name and looks that he was Parsi. I asked Mr. Amir if there was some connection between being Muslim and running a lending library. He said no. Mr. Merchant offered only, “Muslims are good at business,” echoing a stereotype especially of Khojas as premier entrepreneurs.

Says Amir, speaking in round figures, Rita Circulating Library was opened fifty years ago. It has never changed location. I asked, Why did you get into books? “It used to be good money,” he says. “One hundred percent profit.” Or even more. For example, decades ago, he used to buy Gold Key and Dell comics at 8 annas (1 anna = 1/16 rupee) a copy. The borrowing fee then was 1 anna per day, requiring an 8 anna refundable deposit. Older copies he would sell at the buying price, at 8 annas. Some customers might subsequently sell him back the book at half or quarter of that price, and then the cycle starts again. Amir must be talking about the earliest days of his business, for the anna was phased out in the late 50s.

The covers and interiors are often stamped “RITA BOOK STALL” with the address. The back pages of some of the books have markings recording check-out date and fee, sometimes written on separate chits of paper affixed to the back cover or into the binding, sometimes written directly into the artwork’s margins. Today the rental fee is 1 rupee (less than 2 cents USD), with a deposit of 10 rupees. This hardly seems a sum to guarantee the book’s return. But it is also the price if you want to buy the volume outright, horribly beaten-up as most of them are. It gives you a sense of how far down the economic ladder Rita’s clientele resides. These are readers for whom 9 rupees (15 cents USD) makes a difference. And this in the heart of south Mumbai, with no real slums for miles.

The old working class district of Kalbadevi fans out northeasterly from nearby Metro Cinema. While not officially part of Kalbadevi, the area around Rita seems similar demographically. Choked with residents since the British and throbbing throughout the day with pedestrians, over the decades the neighborhood would have provided Rita a steady flow of customers who were neither rich nor poor. Keep this class factor in mind for later. But now customers are very few. Business has been slow for the past ten-fifteen years. “People have no time,” explains Amir. “Television, radio, computer, telephone. They have no time to read.” I asked if some days brought zero customers. He demurred and responded only that there weren’t many.

It struck me that Rita’s holdings are entirely in English. Why not stock Hindi and Marathi books? The readership would be so much larger. But that was precisely the problem. “There are too many authors, too many books. This space is too small.” And Amir is 80. “I am too old to work hard. I have to rest my body. This is easy. This is relaxing.” When I pass by, he is always in the middle of reading the newspaper with his legs stretched across the three-foot span of the store. It is now more his personal office than a livelihood. I suspect the red public phone hosted at Rita beckons more coinage than the books, even with the ubiquity of cell phones. Other English-language circulating libraries in the city seem to be doing okay by stocking new magazines and new media. Amir has simply retired while staying on the job. He is caretaker, in a way, of a living museum. Presumably some things have changed since business turned downward. But I suspect enough has remained the same to legitimately consider Rita today as a kind of time capsule of what a circulating library was like in the recent past. Based on the content, we can roughly identify the age that has been preserved. It’s an important one: 20-25 years ago when economic liberalization radically changed mass entertainment and consumption patterns in India.

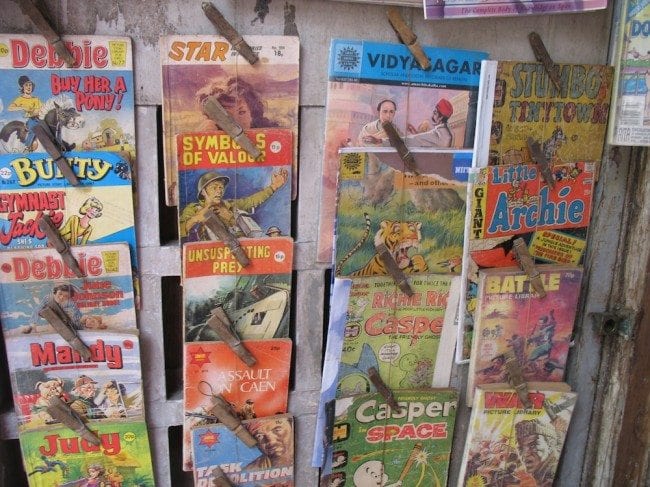

Rita’s comics books, while not the store’s specialty, are a particularly interesting exhibit. Most of Rita’s book inventory comprises trashy 500 page novels, cashier-side harlequin, horror, and detective stuff. But it is comics that front the shop, sitting on cabinets encroaching on the pavement and dangling from clothespins from the opened storefront door. I don’t think Amir has updated his collection in twenty years – which is fortunate for the historian. Offering a snapshot of the kind of comics circulating in India in the late 80s and early 90s, here is a partial list of what Rita has, organized by category. Pocket-size Scottish and British comics: war series like War Picture Library, Battle Picture Library, and Conflict Library; horror from Pocket Chiller Library; girls’ adventure comedies like Judy, Mandy, Bunty, and Debbie; and the romance title Star – which also, as noted earlier, sits static in awesome abundance in a dusty back corner of Victoria Library. Franco-Belgian albums: Spirou, Asterix, Tintin – but no Lucky Luke, which was also sold in India. American comics: a couple Charlton horror issues, some Casper, lots of Richie Rich, and even more Archie family in both magazine and digest format. (Note: the Indian market is flooded with Archie digest booklets. Also available new, street booksellers and circulating libraries are saddled with mountains of copies.) As for Indian comics: an album version of The Adventures of Timpa, Indrajal’s Tintin knock-off; Tinkle, some Diamond Comics, and just a few Amar Chitra Katha. There is one copy of Larry Harmon’s Laurel & Hardy published by Kiran Comics, a company that was active in the late 80s and early 90s reprinting American comic titles. Some of the Richie Rich are also from Kiran, mixed in with original Harvey Comics imports.

None of Rita’s books were made for extensive sharing. To maximize profit, Mr. Amir, like other “circulating librarians,” has therefore had to employ various methods of life support. Most of the novels have plastic covers, as do pamphlet-sized comics like the British Pocket Chiller Library and India’s Diamond Comics. Most of the saddle-stitched comics are fortified with string bindings. This reminds me of Japan. Similar techniques were used to keep rental kashihon manga in circulation during the 50s and 60s. Today it is hard to find copies of old kashihon manga without transparent vinyl glued to their covers, or without holes bored in the binding for string, or without tape and scrap paper affixed to the endpapers to keep the cover attached to the body. In Japan, “circulating libraries” were numerous and successful enough to support its own publishing market separate from the retail trade. Thus many books were physically designed to weather circulation. Thus most kashihon manga were hardcover between the early and late 50s, at which point fat but sturdily bound softcover anthologies began to dominate. Romantics like to associate the kashihon library solely with the horror, gang, and violent samurai and ninja material found in these rental-oriented volumes. But, as in India, mass-market magazines also circulated through Japanese rental libraries, capitalizing on a readership hungry for mainstream manga but too poor to purchase copies for themselves. With thick string holding together their vinyl-fortified soft covers, these accidental kashihon look a lot like the books at Rita Circulating Library. I wonder if Indian parents ever complained, as Japanese parents did in the 50s and early 60s, of rental books being vehicles of filth and bacteria.

None of Rita’s books were made for extensive sharing. To maximize profit, Mr. Amir, like other “circulating librarians,” has therefore had to employ various methods of life support. Most of the novels have plastic covers, as do pamphlet-sized comics like the British Pocket Chiller Library and India’s Diamond Comics. Most of the saddle-stitched comics are fortified with string bindings. This reminds me of Japan. Similar techniques were used to keep rental kashihon manga in circulation during the 50s and 60s. Today it is hard to find copies of old kashihon manga without transparent vinyl glued to their covers, or without holes bored in the binding for string, or without tape and scrap paper affixed to the endpapers to keep the cover attached to the body. In Japan, “circulating libraries” were numerous and successful enough to support its own publishing market separate from the retail trade. Thus many books were physically designed to weather circulation. Thus most kashihon manga were hardcover between the early and late 50s, at which point fat but sturdily bound softcover anthologies began to dominate. Romantics like to associate the kashihon library solely with the horror, gang, and violent samurai and ninja material found in these rental-oriented volumes. But, as in India, mass-market magazines also circulated through Japanese rental libraries, capitalizing on a readership hungry for mainstream manga but too poor to purchase copies for themselves. With thick string holding together their vinyl-fortified soft covers, these accidental kashihon look a lot like the books at Rita Circulating Library. I wonder if Indian parents ever complained, as Japanese parents did in the 50s and early 60s, of rental books being vehicles of filth and bacteria.

Rita is a special place. While generally similar to the holdings of other circulating libraries in Mumbai, Abdullah Amir’s refurbishments reflect an artistry that I have otherwise never witnessed in Japan or India. Amongst old kashihon, one often finds magazine pages used to reseal bindings, repair endpapers, or create new covers. But I have only seen one or two examples in which repair materials were consciously chosen to visually embellish or complement the subject matter of the comic within. Amir has exploited this idea and turned it into an art – a shabby amateur art, sometimes a barely recognizable art, but an art nonetheless with a sense of humor and poetry in tune with the its times: the economic liberalization and cultural globalization of India that took place in the 80s and 90s.

Rita is a special place. While generally similar to the holdings of other circulating libraries in Mumbai, Abdullah Amir’s refurbishments reflect an artistry that I have otherwise never witnessed in Japan or India. Amongst old kashihon, one often finds magazine pages used to reseal bindings, repair endpapers, or create new covers. But I have only seen one or two examples in which repair materials were consciously chosen to visually embellish or complement the subject matter of the comic within. Amir has exploited this idea and turned it into an art – a shabby amateur art, sometimes a barely recognizable art, but an art nonetheless with a sense of humor and poetry in tune with the its times: the economic liberalization and cultural globalization of India that took place in the 80s and 90s.

I admit that my knowledge does not extend very far in this matter. But to my knowledge, there was no Pop Art upsurge in India in these years, which is curious. The United States, Britain, Western Europe, Japan, Russia, and China: all produced a large number of artists working in an ironic Pop idiom as their populations adapted to American-style consumer culture, whether in the wake of postwar Pax Americana in the 50s and 60s, or in the Communist bloc’s compromise with capitalism in the 1980s. Whatever the reasons – a weak art market, the offsetting effects of a strong local tradition of pop and mass culture, the absorption of Pop impulses by Postmodernism – nothing comparable seems to have emerged in India. I think we might consider Amir’s repair work a petit expression of this elusive Indian Pop. A poor man’s Pop Art, for sure. And a rarity: Pop Art with a function.

Some of Amir’s comics are impressive simply for their physical tenacity. While there are some page fragments, coverless books, and bookless covers in his comics collection, Amir’s did his best to keep a comic book alive, to make it work and bring in money for as long as possible. Rita is like a field hospital with no qualms about returning battered soldiers to battle. A cover can be sacrificed if the book can be saved, for example. Or, the first four pages can go if the cover can be saved. Such is the case with a copy of Tales of Shiva from Amar Chitra Katha. Rita has the original edition from 1978, and time has been hard on it. The surviving pieces of the cover, which is utterly mangled, have been pasted onto card stock. Pieces from a deceased Archie comic have been used to the fill in the blanks. One can start reading only from page five because the glue from the cover has absorbed the first four. One rupee for the night doesn’t seem like such a great deal after all.

Some of Amir’s comics are impressive simply for their physical tenacity. While there are some page fragments, coverless books, and bookless covers in his comics collection, Amir’s did his best to keep a comic book alive, to make it work and bring in money for as long as possible. Rita is like a field hospital with no qualms about returning battered soldiers to battle. A cover can be sacrificed if the book can be saved, for example. Or, the first four pages can go if the cover can be saved. Such is the case with a copy of Tales of Shiva from Amar Chitra Katha. Rita has the original edition from 1978, and time has been hard on it. The surviving pieces of the cover, which is utterly mangled, have been pasted onto card stock. Pieces from a deceased Archie comic have been used to the fill in the blanks. One can start reading only from page five because the glue from the cover has absorbed the first four. One rupee for the night doesn’t seem like such a great deal after all.

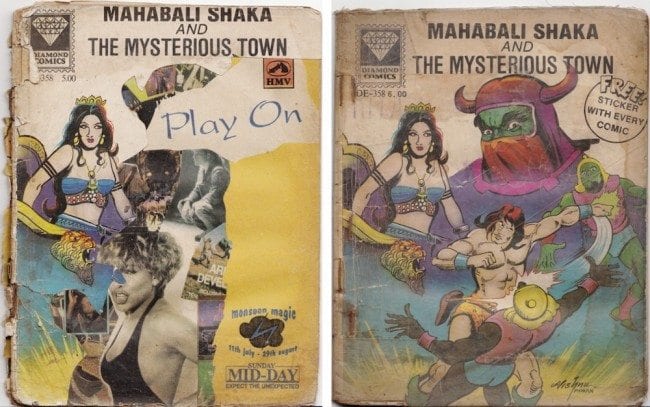

This sort of distressed, decollagist aesthetic is more artfully accomplished in other samples. Buried at the bottom of a dusty pile, Amir has a large caché of old Diamond Comics, including a number of my new favorite Indian comic book hero, Mahabali Shaka, a degenerated hybrid of Tarzan and Conan. A reader must have liked the action figures on the cover of Mahabali Shaka and the Mysterious Town, for they have been clipped out along their outlines. A later edition of the same title at Rita (this one protected with a plastic cover) shows what’s gone.

Where Mahabali Shaka and the green fiends once were, now stands Tina Turner at her sexiest, with Richard Marx above her and Bobby McFerrin to her left. It’s an advertisement for HMV records, and on its versa (serving now as the inside front cover) is another ad for “Hartbustin rap and disco” cassettes, including Arrested Development’s Unplugged (1992) and KWS’s “Please Don’t Go” (1992). Unless he was using older magazines at a later time, we can date this collage more or less precisely to a year or two after India began its economic liberalization in earnest in 1991.

By itself, this repair job would not leave much of an impression. Considering other comics at Rita, however, it is clear that Amir was trying to embellish his broken books with the hottest in contemporary pop culture. The inside back cover of Tales of Shiva, for example, is fortified with a section from a movie magazine cover featuring Shahrukh Khan, dated 2009. In the original comics, this was the place typically for advertisements for other ACK and Tinkle products. By substituting Bollywood’s new bad boy and hip foreign music stars, Amir reroutes the kids’ comic into a more mature circuit of consumption and fantasy – one probably more in line with readers’ actual desires than the moral examples of ACK’s mythological heroes and freedom fighters.

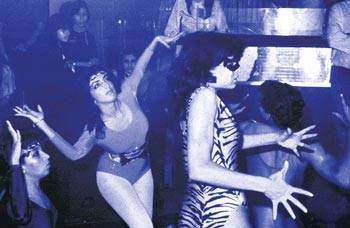

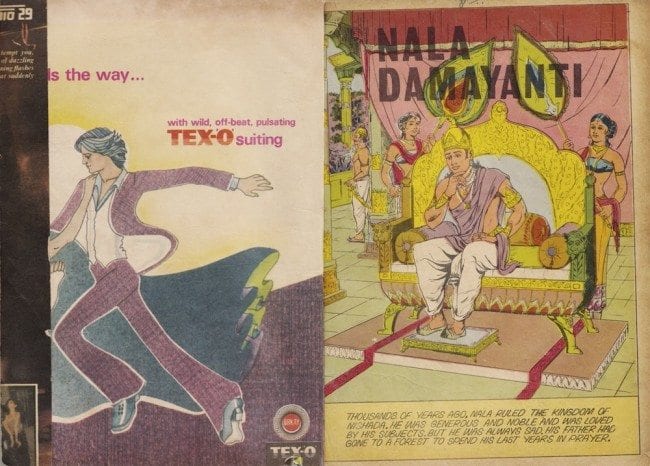

Other repaired comics prove the point convincingly. Take Rita’s copy of Nala Damayanti, an early ACK title from 1971, this one about a handsome, virtuous, and heartsick king and his devoted, head-turning beloved. Amir has given this romantic morality tale from the Mahabharata a strange new cover: pages from a magazine feature on Studio 29, Mumbai’s legendary members-only discotheque, named after New York’s Studio 54 and just as much a magnet for the city’s celebrity demi monde. Opened in 1980 inside the Bombay International Hotel (now Hotel Marine Plaza on Marine Drive), Studio 29 was immortalized nationally as a den of bizarre and dangerous pleasures after being depicted as such in Janbaaz, a steamy Bollywood flick from 1986. The musical number “Give me Love,” featuring ululating negresses, lip-licking blondes, and breakdancing savages, was staged entirely on Studio 29’s dance floor. Watch the video; it’s fantastic.

Amir has used a tamer image with pedestrian dancers. “Once you enter Studio 29, there is no way you can avoid getting on to the floor and boogying,” reads a caption, citing one Mick Jones. “If the music does not tempt you,” another explains clinically, “Jones has rigged a bunch of dazzling effects from lightning flashes to thousands of bulbs that suddenly envelope the dancer.” Then, opening to the first page, the pining Hindu king looks across from his lonely throne to an advertisement for “wild, off-beat, pulsating Tex-O suiting,” a fab polyester get-up for the modern disco man. With a little knowledge about Indian visual culture, one could probably pinpoint the date of Amir’s redecoration. Considering that Studio 29’s popularity peaked in the mid 80s, I assume it’s from then or a little later.

As I will describe below, a new culture of money and consumption was growing rapidly in this period. As proprietor of a store servicing children in India’s most affluent and glamorous city, Amir would have had a sense of the contours of this developing culture simply through knowing what children liked to read. Tellingly, the majority of the comics at Rita belong to the Archie line. While these have survived fairly intact and the repair work on them is uninspired – a Josie and the Pussycats issue with Shahrukh Khan endpapers is about as interesting as they get – it is worth noting their bountifulness. This comic book about American suburban white kids was once popular enough to stock en masse. Clearly that popularity has waned, because the Archies now sit there untouched, as they do in large numbers at Victoria Library.

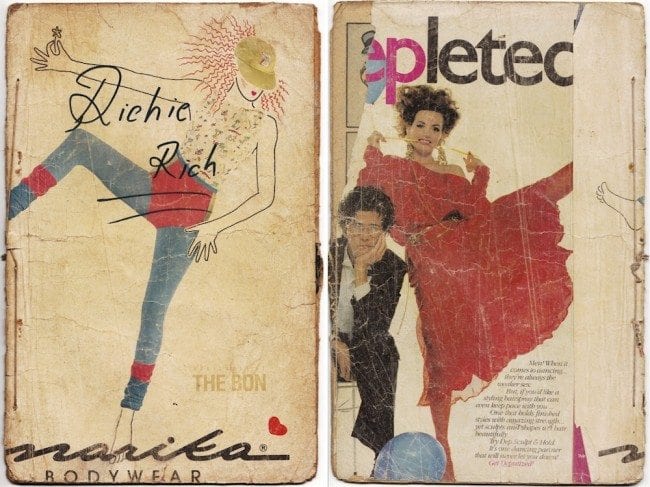

More interesting are the Richie Rich issues. There are only a handful. Amir has singled them out and put a little extra into their rehabilitation. In place of the wealthy and ingenuous blonde cartoon kid, the covers of some Richie Rich issues now feature images of wealthy white people taken from luxury advertisements in British fashion and lifestyle magazines. The “Richie Rich” scrawled on these new covers, sometimes more than once, seems as much a description of the cover images as the content inside.

Inside one front cover, a lady in a “mid-calf cashmere coat-dress,” pearl necklace, and gold earrings shows off her 7000 UK pound ensemble while, on the facing page, Richie Rich withdraws a sack of dough from the bank.

Isolated, one might not make much of the melancholic Indian prince Nala gazing upon images of Studio 29 and polyester suits. But considering that dance reappears in a refurbished Richie Rich issue as well, Amir was probably poking fun at disco as a pastime of Bombay’s affluent youth. The front cover advertisement is for Marika Bodywear, fashionable exercise clothing for aerobics, jazzercising, and the like. The back cover is an ad (with more white people) for Dep hairspray. “Men! When it comes to dancing . . . they’re always the weaker sex. But if you’d like a styling hairspray that can even keep pace with you . . . Try Dep Sculpt & Hold. It’s one dancing partner that will never let you down!”

This benched fellow might sulk, but not Richie Rich. Beneath these ads are the comics’ real cover, showing “the poor little rich boy” holding his own on the disco floor, his blonde do kept in place probably with nothing more advanced than a comb and pomade. Situated above Rich’s dancing partner is a small text inverted: “Tonight, nothing.” Amir, the socio-cultural observer, was also a smalltime poet.

This is the kind of art teenagers, of my generation at least, made in their diaries. I am not saying that Amir’s collages are masterworks. But given that the origins of Pop Art globally are credited to such remedial artistic expressions as Eduardo Paolozzi’s scrapbooks from the late 40s and Ray Johnson’s collages from the mid 50s, surely room can be made in art history for someone like Abdullah Amir. It is interesting that a middle-aged bookstore and rental library proprietor would have been decking out his stock in this fashion in the 80s and 90s. On the one hand exercising a little artistic creativity to attract potential readers’ attention by plugging into contemporary fashion, he was also making light jokes at the expense of that very same milieu. Pop Art is often described as having an ambivalent stance toward consumer culture, celebrating its glamour while also jabbing with irony at its vapidity. Amir has (to use the militant vocabulary of self-aggrandizing art criticism) “deployed a similar strategy.” Perhaps not so rich in allegory as the tableaus of the Pop Art cannon, at least Amir’s collages are situated in the field, in a place where people actually consume pop culture. High Pop Art might wage a more sophisticated battle, but it does so only from the detached encampments of the gallery and art magazine, where they can only be officers’ war games with little actual engagement with the real thing.

This is the kind of art teenagers, of my generation at least, made in their diaries. I am not saying that Amir’s collages are masterworks. But given that the origins of Pop Art globally are credited to such remedial artistic expressions as Eduardo Paolozzi’s scrapbooks from the late 40s and Ray Johnson’s collages from the mid 50s, surely room can be made in art history for someone like Abdullah Amir. It is interesting that a middle-aged bookstore and rental library proprietor would have been decking out his stock in this fashion in the 80s and 90s. On the one hand exercising a little artistic creativity to attract potential readers’ attention by plugging into contemporary fashion, he was also making light jokes at the expense of that very same milieu. Pop Art is often described as having an ambivalent stance toward consumer culture, celebrating its glamour while also jabbing with irony at its vapidity. Amir has (to use the militant vocabulary of self-aggrandizing art criticism) “deployed a similar strategy.” Perhaps not so rich in allegory as the tableaus of the Pop Art cannon, at least Amir’s collages are situated in the field, in a place where people actually consume pop culture. High Pop Art might wage a more sophisticated battle, but it does so only from the detached encampments of the gallery and art magazine, where they can only be officers’ war games with little actual engagement with the real thing.

Amir’s Pop is not always satirical. There is a suite of Richie Rich covers of a more purely aesthetic orientation, in which visual composition is more important than ironic juxtapositions of interior and exterior. Panels from other Richie Rich comics – probably salvaged from junk issues – have been glued to glossy magazine advertisements, serving to identify the comic book through pictures of the hero as well as through a hand-scrawled title. At the same time, a small sprout of narrative hooks a potential reader’s attention. This bud can suggest greater adventures to come, like in the two-frame cover below showing Rich about to hop into his cave boat, placed artistically at angles across an image of an envelope.

Another panel from the same adventure has been affixed to a second comic book, this time with an injection of the absurd. We see here another common Pop Art technique: the isolation of a single element from an ad or a comic book page, focalizing attention on its internal components through framing or enlargement, letting the humor of the selected element express itself more clearly without interference from the narrative flow of the original context.

And last, there is this multi-element cover, the most complex composition at Rita. Across three panels that were probably adjacent in their original context, Richie chases his butler through his mansion, trying to find out what’s in the package he’s holding. As in the mountain goat cover, Amir is playing here with a viewer’s curiosity for the unknown. I suspect a reader added that rectangular polyhedron in blue pen, top left. If so, it is a curious addition, a 3D evocation of the architectural space within which Richie and his butler race around.

And last, there is this multi-element cover, the most complex composition at Rita. Across three panels that were probably adjacent in their original context, Richie chases his butler through his mansion, trying to find out what’s in the package he’s holding. As in the mountain goat cover, Amir is playing here with a viewer’s curiosity for the unknown. I suspect a reader added that rectangular polyhedron in blue pen, top left. If so, it is a curious addition, a 3D evocation of the architectural space within which Richie and his butler race around.

I don’t mean to elevate Amir’s garage art any higher than what it is. It is the combination of work and context that I find interesting, the appearance of these Pop gestures upon Western comic books within a circulating library just at the point when India was about to go whole hog for globalized consumer capitalism. It is suggestive that the bulk of Rita’s comics are Archie and Richie Rich. Most people regard Amar Chitra Katha as the middle class Indian comic par excellence. “I do not know of any middle-class Indian home,” wrote a journalist in 1990, “that has not at one time or the other subscribed to Amar Chitra Katha. It is a byword among children.” Yet ACK was also largely out of fashion by the late 80s. It even ceased publication of new titles for a time in the 90s. My interviews with Gen X Indian comics people, few of whom profess special nostalgia for ACK, seem to support this. What to make of the fact that at Rita, the present stock of which seems to date from the 80s and 90s, there are only a few issues of ACK, some of which are first editions from the 70s? Perhaps there are so few because they were so often borrowed that they disintegrated. Or perhaps it is because kids from that era preferred instead stories based on cushy and carefree Western lifestyles – precisely the kind of thing that ACK, with its commitment to “Indian themes and values,” is said to have been designed to combat.

There’s a history behind this archive. Not being an India specialist, I proceed with hesitation. But if Pavan K. Varma’s controversial The Great Indian Middle Class (1998) accurately narrates the rise and constitution of what is now the country’s most talked-about echelon, then Amir’s petit Pop is a lucid historical record. According to Varma, middle class self-interest in India only really came into its own in the 1970s. Previously it was held in check by a Gandhi-Nehru example of prudence, ideals of asceticism, support for progressive politics, and self-reliant nation building. It is often said that with Nehru’s death in 1964 that moral order lost much of its restraining tension. Whatever venality it held back was only encouraged by the examples set by the leadership of Nehru’s daughter, Indira Gandhi, under whom corruption and the naked exercise of power flourished. According to some writers, it was against the backdrop of this ideological ruin that, alongside more extreme forms of Hindu nationalism, the supposedly regressive historical project of Amar Chitra Katha rose to prominence and, in the words of scholar Deepa Sreenivas in his book on the famed comic book series, “moulded the self-image, character, and imagination of hordes of middle-class children in the India of the 1970s and 1980s.”

But let us not forget the essential factor of class: money. Hinduism and Independence might very well be important touchstones for Indian middle class identity, but they have been thoroughly refitted to accommodate the desire to have and have more. While Indira Gandhi was busy finishing off the post-Independence political consensus with the Emergency, liberalization of the domestic economy was increasing the ranks of upwardly mobile Indians. A new generation of middle class Indians emerged. According to Varma, “The ‘new rich’ may have lacked a certain kind of ‘upbringing’ – a point of comment for the more exclusive in the traditional middle class – but they also had much more of what really mattered: money. ‘Upbringing’ could not be bought for money; but money could certainly compensate for it by bringing in more of the things – a car, a TV, a music system, the entire range of ‘foreign goods’ – that now even the more ‘well-bred’ hankered for.”

During the 80s, writes Varma, during Rajiv Gandhi’s tenure as Prime Minister (1984-89), this consumerist identity began to be projected outwardly and confidently as integral to the nation’s future. It was further emboldened after the country opened its doors to foreign capital and goods in 1991. “Overnight the consumerist thirst of the middle class became an asset, a sign of the dynamism of the Indian market.” Inhibitions toward acquisitiveness, already weak, were then discredited as liabilities against the nation’s progress and international stature. Gurcharan Das, a prominent author, former CEO of Procter & Gamble India, and vocal apologist for growth, put it differently in 1996: “Gone is our earlier hypocrisy towards money.”

As for the readers of Rita Circulating Library’s comic books: given the store’s location in Marine Lines and near Kalbadevi, its clientele would have been largely lower middle and working class, and fairly distant in economic terms from the “new rich” that Varma describes above. But living in the entertainment and financial capital of Bombay, they would have been fully exposed to that rising class’s radiating halo of wealth and glamour. Considering the amount of trade and small industry in the area, entertaining hopes for drastic upward mobility would not have been entirely delusional, at least for some. And presumably more agog than parents were the neighborhood’s children. One need only look at the Indian middle class today to see that the self-interest and acquisitiveness embraced by people born around the time of Independence only redoubled with their children, whose desires were further flamed by more money and, increasingly after 1991, more things on which to spend that money.

The role of television was great. Previously broadcasting had been limited to a single state-controlled channel known as Doordarshan. Content widened and improved thanks to Rajiv Gandhi’s avidness for the medium. With the introduction of first private (non-licensed) sets and then, in 1993, foreign satellite broadcasts – led by Star TV in Hong Kong, provider of BBC and MTV – cultural globalization inundated India. Cutthroat scholastic competition and working parents’ absence from home, leading to children’s unmonitored attached to television, only exacerbated the situation. Varma again: “The consumerist messages from society, and especially from television are relentless. Children are growing up with a single-minded focus on acquiring these objects of desire, and are willing to orient their lives almost exclusively towards this end.” Another contemporary observer explained, “It’s the middle class children who have to bear the brunt of a rapidly changing society in which restraining traditions have been offloaded in a single-minded pursuit of plenty.” Such concerns might seem old hat to citizens of the developed world. But they were fresh and sharp twenty years ago in India. ACK-founder Anant Pai felt them keenly: in 1990, he blamed the comic book series’ decline on the spread of satellite television and video. Nandini Chandra, author of the impressive The Classic Popular: Amar Chitra Katha, 1967-2007 (Yoda Press, 2008), puts the responsibility instead on editors’ lack of creative vision in the mid-late 80s, sabotaging ACK’s reputation and quality by reducing new comics to accessories to popular television programs like Doordarshan’s Mahabharata. But maybe the problem was also that ACK was offering a dated kind of role model. Honor, the family, and the nation were admirable goals, but for an Indian child in the age of liberalization, how could they compete with television’s commodity splendor or the emancipatory promise of private wealth?

Against this backdrop, it is already easy to understand the appeal of Archie and Richie Rich. But let me render the outlines sharper with two further examples. Like most other accounts of the Indian middle class, Varma identifies Rajiv Gandhi as an important figure in the country’s transformation. It was not only in his economic policies that Rajiv embodied the aspirations of the upwardly mobile. Equally important was his personal look and conduct. “The dhoti-kurta clad politician travelling in third class compartments is an image of the past,” claimed a journalist in 1988. “Today’s rulers sport Gucci shoes, Cartier sunglasses, and live five-star lifestyles.” The contrast had already been made in 1985 in an article on “India’s yuppies” in the New York Times: “Indira Gandhi scornfully called them ‘the five-star culture,’ but India's newly affluent, Western-oriented, younger businessmen, managers, technocrats and professional people are the soulmates of her son, Rajiv Gandhi.”

Biographer Attar Chand, in a book on Rajiv published the year of his assassination in 1991, wrote the following: “Because he personified the yuppie lifestyle, combining consumerism with class, it lent respectability to this cultural phenomenon. His Gucci shoes may have been the butt of many jokes, but he persisted with them unfazed. He didn’t mind being photographed wearing Levi’s jeans, T-shirt, and hat, a camera slung from his shoulder and fishing rod in hand, when he went holidaying with his family in Mizoram in 1985. Indeed, he persisted even with his holidays despite squeals of derision when he had Amitabh Bachchan and Sonia Gandhi’s relatives accompany him on cruises to the Andamans and Lakshadweep. The message that went out was clear: The middle-class need not be apologetic about being itself, doing the things it liked doing. For those who afford it, these were things to aspire to.” Again Chand, looking back from 1991, which was also the year of India’s full embrace of economic liberalization: “To look for memorials to Rajiv Gandhi, one has only to step inside any middle class home, past the Maruti car or van parked outside. The colour TV, the VCR/VCP, the washing machine, ethnic pillow covers, and branded clothes or shoes are only a few examples of how life has changed since Rajiv.”

Yet, fantasy and reality do not often match up. If class is an economic category, it is also entails a mindset and aspirations. Admiring wealth and leisure is not the same as living in Archie’s Riverdale, let alone in Rajiv “Richie Rich” Gandhi’s mansion. Graphic novelist Sarnath Banerjee’s autobiographical contribution to the recent Pao anthology of comics (2012), “Tito’s Years,” amusingly captures the contradictions of this transitional era. “There was a time, not so long ago,” Banerjee begins, “when children played hockey, boys were named after Marshal Josef Broz Tito and a pair of Nike shoes stood at the pinnacle of aspiration. They were impossible to acquire is pre-liberalized India.”

Banerjee was born in 1974. Tito, a leader of the Non-Aligned Movement alongside Nehru and Nasser, died in 1980. See how the dates fit Varma’s timeline of the transformation of the Indian middle class. Later, the Summer Olympics in Los Angeles (1984) are cited as the galvanizing “Nike fest” after which Indian kids began clamoring for the company’s shoes. By attaching booster antennae to Calcutta’s rooftops (Banerjee is from Calcutta), families reached out and grabbed signals from Bangladesh, thus channeling into Indian homes yet more American images. “A beautiful world of education unfolded before our eyes,” writes Banerjee sarcastically beneath a drawing of J.R. Ewing in front of the Southfork Ranch from Dallas. One friend, the eponymous Tito, is blessed by heaven when he receives a pair of new Nikes from his uncle in Ohio. Banerjee desperately wants his own pair. A tattered set arrives with a cousin visiting from Cincinnati. But Banerjee’s Nehru-Tito-era father is furious and throws them out, only to capitulate later to his son’s broken heart by trying to create a pair of fake Nikes with blue paint applied to local Bata sneakers.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the subcontinent, Rita Circulating Library was grappling with liberalization in its own way. Remember that Rita’s books are all in English. It has catered exclusively to the Anglophone middle class. The store’s tiny size and shabby stock might not coincide with the stereotypical image of rabid middle class consumption, but that is precisely the point. The Indian middle class, writes Varma, is “the middle class of a poor country.” Even today, despite the influx of foreign goods, not all of middle class Indians have the money to obtain them. As discussed in my interview with Leaping Windows, even imported American comics are too expensive for most. Despite mass media images of plenty, to this day basic amenities like electricity and water are not reliable even for those with money. One can thus imagine just how much more brilliant would have been Archie’s neighborhood or Richie Rich’s kingdom. Add to that the likelihood that Rita’s clientele belonged to the lower middle class, for whom rental versus purchase was a choice with economic implications. One rupee for a billion dollar adventure. A single rupee for a world in which there was no greater worry than the jealousy of a sweetheart from the American suburbs.

Born in the 1940s, Amir could not but have felt sharply changing times and values. Indian kids came to his store, preferring British romance and American humor comics that depicted the fun and easy lives of the middle class and rich of the Anglophone West. Perhaps those kid readers could not afford to buy copies of their own – though Amir did say he used to sell many books – or perhaps their parents exercised a little (Mahatma) Gandhian prudence in their kids’ allowance. The appeal of monied life would have been strong, nonetheless. And so to put those comics and their fantasy worlds in the right context, Amir wrapped them in ads for luxury goods, images of Bollywood stardom, and photographs of the absolute pinnacle of glamorous nightlife: dancing at Studio 29. If Rita’s collection provides a snapshot of what Indian kids read in the late 80s and 90s, so Amir’s doctored covers capture the irony with which an older generation beheld Indian’s consumerist upstarts and the changes wrought by globalized media. Television, after all, was one of the things Amir blamed for his retreating business.

A poor man’s Pop Art, is how I described Amir’s covers earlier. But it is as Pop Art of a poor man’s country that they are particularly interesting.