An image. A person walks alone in the wilderness and comes upon a pond. Turtles swim in the pond; the person bends down towards them before kneeling. Finally, sat on his knees, he looks at the pool, his head slightly bowed, eyes narrow as he searches for something he cannot quite define. Away from him, on the edge of the panel, dark splashes of color begin to take over, reflecting something quite unnatural. It’s a beautiful image, softness moving towards danger, a restless spirit in search of peace; worthy of Miyazaki. One odd thing - the person in question is a ninja turtle. Not that it detracts from the dignity of the scene one iota. Such is the work of Sophie Campbell.

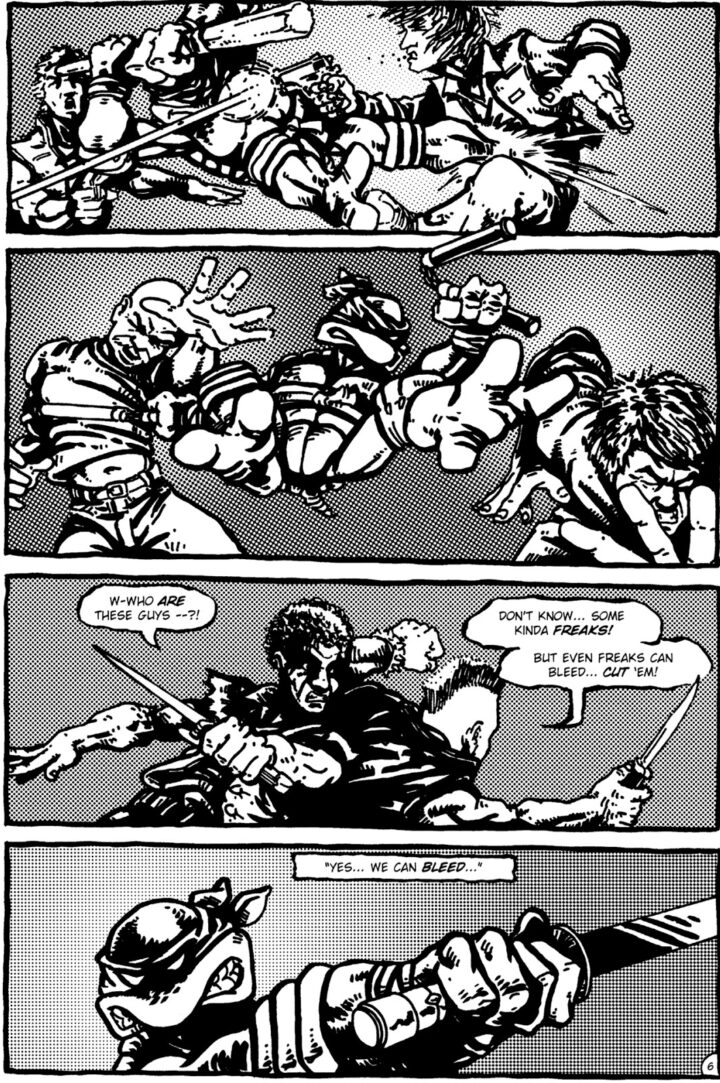

The particular strength of Campbell’s art, which is also mirrored in her writing, is exactly that - the dignity she affords all of her characters. You can see it very early in her career (more on that later), but for now let’s keep the focus on Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Precisely because this is not a title, a franchise even, one associates with words like ‘dignity’ or ‘beauty’. Partly it’s because the very concept is so ridiculous, and partly because of the grimy nature of Eastman's and Laird’s artwork. These first few TMNT comics are damn ugly! This isn’t a negative judgment, by the way; this ugliness, the sort of raw primitivism backed only by the self-belief of the amateur, gave rise to the most unlikely empire in entertainment. The pair wrote and drew an ugly comic about an ugly world, awash in crime and filth; a Cannon Films version of New York City (with prerequisite American Ninjas). Which is why it was so weird it became a successful toy line and a cartoon. And then another cartoon and another toy line. Then another. And another.

In 2011, the comic book series was relaunched, this time under the banner of IDW (whose hunger for toy-based properties knows no bounds), written by Kevin Eastman and Tom Waltz, and drawn by a rotating crew of artists. The series has proven enough of a success, in IDW terms, to not only make it to over 100 issues, but also lunch a number of spin-offs. Campbell, having worked on the previous Mirage series, was recruited to draw several of these issues, and found herself a repeating guest. Her art always stood head and shoulders above the competition in pretty much in field you want to name. Her action scenes are bold and kinetic (and can be quite brutal), she’s great at character acting and facial expressions (not easy when all your main characters share basically the same character model), and she has a good sense for when to fill out the writerly details and when to just pull back and let the image speak for itself.

The above page is a great study of controlled expressions, telling everything you need to know about the mood of the scene and of the various participants, without the need for words: the semi-forced smile on the first panel, an attempt to create joviality that isn't there, which quickly shifts into the acceptances of sadness. The realization that one cannot simply wash away the large issues these people deal with.

More than all of this, the thing that’s notable about Campbell’s art is the innate dignity she affords all of her characters. It’s easy to make the TMNT concept into a joke -- that’s pretty much how it started -- but in Campbell’s hands TMNT is a story about reacting to changes, physical and mental, and, especially, dealing with the way society reacts to these changes. With issue #101, Campbell became the main writer and artist of the series (though other artists began contributing before very long), which led with a massive shift in the status quo of the series: a large chunk of New York city has been deliberately mutated, creating seemingly thousands of human-animals hybrids. This new Mutant Town is sealed off from the rest of the city, and the world. The protagonists no longer needing to play ninja and hide in the shadows, but are forced into a far more complicated position - that of community organizers, social activists, and politicians.

Another good example of Campbell's artwork is this one, from the penultimate issue of her run as artist on the 2012-13 revival of Rob Liefeld's Glory. None of the original Liefeld designs are that great or memorable - the lady characters in particular were pretty much all of a type, but Campbell somehow forces them into greatness in this page. Both Glory and Masada are big buff ladies, but now they are different types of big buff ladies; you wouldn't confuse them with one another, they are not separated just by differently colored bathing suits. These figures all look unique and interesting now, even though some of them are just variations on one another ("New Fourplay" and "Even Newer Fourplay"). Most of these characters would only appear on this page and off to the side of one panel later on, but Campbell doesn't treat their reinvention as a mere gag.

Back to the Turtles: There’s still ‘ninja stuff’ -- fighting and jumping and big scary monsters -- but more and more it’s a sideshow to the main event: the exploration of both characters and society, from micro to macro. The various Turtles begin to reject their natural first response, violence, in favor of compromise and open dialogue. The obvious point of comparison is another highly-rated IDW series based on a 1980s toy line, Transformers: More than Meets the Eye, which picked up the franchise with the big war that defined the concept since its inception having concluded. What do you do when the only thing you ever did is over?

Speaking of other comics, let’s not ignore the elephant in the room. There is, after all, another rather successful franchise about mutant heroes that recently tried to move away from traditional superheroics to science fiction utopianism and nation-building. Naturally, writer Jonathan Hickman’s work on various X-Men titles got a lot more attention in the comics press. Serendipity, I guess; it wouldn’t be the first time in comics for similar ideas to appear at the same time (e.g. Dennis the Menace and the other Dennis the Menace both debuting on opposite sides of an ocean in March of 1951). However, while the surface details are similar enough, the differences are quite stark and demonstrate clearly why Campbell’s version works better.

The simple fact is that Hickman is telling a story about nation-building without any effort put forth. The new Mutant Country is built between panels, and achieves global dominance at the same pace. Characters who previously tried to murder each other on a daily basis can now sit together and easily agree on both pizza toppings and the overall goals of the mutant community. It’s all too easy. And despite starting with the nation already in place, it's up to the various spin-off titles to establish something about the actual daily culture of an entire country, rather than the stuff that’s directly tied to super-people going out and doing flighty stuff. It’s all about the resurrection.

It’s possible that Hickman actually thought these issues through, and was hampered by the corporate need to still publish X-Men-just-as-you-know-them titles. Despite the bold new direction™, there’s still a whole lot of issues focusing on the same old business of evil anti-mutant groups. One step forward, two steps back. In Campbell’s TMNT, things are never easy. The new community, composed of many people who didn’t ask to be like this, is fighting over everything - definitions, resources, leadership. People had their whole lives turned upside down in a moment, and are now trying to adapt. Surely you can see why this approach is a lot more interesting that the Marvel titles' odd hivemind edict, a plot device by which all the characters easily adopt a collectivist mindset in order to explain how this new society came to be so quickly and manages to function beyond day one; and yet, this edict is only in effect until the plot needs the characters to bicker and argue like regular people (because personal drama is what has sold X-Men comics for ages). As a result, there's no consistency of agreement between titles across the line.

People -- or, rather, something more nebulous like ‘humanity’ -- were never Hickman’s strong suit. Most of the time he writes like the old science fiction authors that treated characters as mere carriers for whatever crazy idea they'd thought of next. Except it’s the 21st century now, and Hickman seems to believe no one else is aware of Cordwainer Smith (or even Greg Egan). Campbell’s writing, comparatively, is all about the people; all about their tiny lives and tiny struggles and tiny loves, and how all of them come together to make this one big thing.

When Mona Lisa, a previously-human person who is now a talking salamander, vents in a mutant support group, we are with her. We are even with her as she lashes out at Michelangelo, even though he’s a protagonist and she’s just a side character. We are also with everybody else in that group: a dozen newly introduced characters, each fully-formed with their own reaction to event that changed, their own bodies, their very self. When I called Mona Lisa a ‘side character’ I was simplifying Campbell’s work with the title – there are no side characters. There just people: salamander-people; turtle-people; elephant-people. And all people are equally valid in their existence.

You can see this sort of thing early in her career. Shadoweyes, originally published by SLG (2010-11) and later collected in color by Iron Circus (2016), also concerns a human girl, Scout, transformed against her will into a mutated super-being. At first it seems like Scout would go through the usual arc that cape comics afford such characters - fighting crime while searching for a cure to her condition. Yet, almost immediately, the book ventures off the beaten path. Not only does Scout learn to accept her new form, other people in her social circle learn to accept it. ‘Accept’ is probably too weak of a term here - she learns to love it. One morning, when Gregor Samsa woke from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a beautiful butterfly.

The other things Shadoweyes shares with Campbell's TMNT run is its complex relationship to the issue of being a superhero. Scout begins by thinking in terms of ‘crime fighting’ - just jumping through the streets and pouncing on random muggers. But she quickly grows uncomfortable with this act. The mugger is some desperate teen with anger issues; the supposedly sinister attacker is just some guy having an argument on the streets. You can’t just punch these problems away. Trying to do good is a lot harder than it seems like at first, because that involves figuring out what ‘good’ is. But unlike other would-be-revisionist takes on the superhero formula, the story doesn’t simply give up on the notion once it discovers how hard it is.

Artistically, as one would expect, the older Shadoweyes is slightly less accomplished. The cartooning tends toward exaggeration; the shorter characters appear to be almost half the size of the taller ones; character forms feel flat on the page; the backgrounds seemed taken from dystopic science fiction city 101. Still, even so early, the qualities of Campbell’s art are already in evidence. Characters of all body types inhabit the page naturally, with no special attention called to the fact the some are skinny, some chubby, some fat, some extremely buff. Scout’s transformation, and her acceptance of that transformation, feels like a natural extension of the story’s casual acceptance.

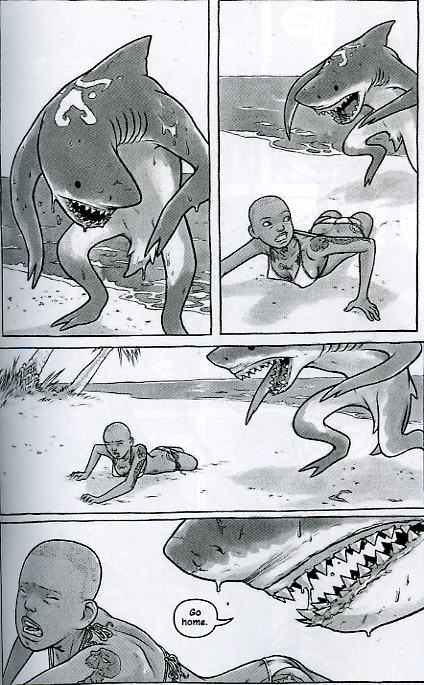

The themes of transformation are also evident in the artist’s less supernaturally-inclined works. Water Baby, a one shot for DC’s abortive Minx line of young adult graphic novels, deals with a surfer who needs to adjust to life after losing her leg to a shark attack. Most of the Minx line hasn’t aged too well, but Water Baby stands out, both in its emotional frankness and in its willingness to let its main character act like an occasional jerk in response to trauma without becoming too judgmental or pretending she can just ‘get over it’. This isn’t a story about ‘overcoming’ change, but about accepting it and growing with it. Brody is a different person than she was before the attack; not a worse or better person, just a different one.

Likewise, Wet Moon -- Campbell’s long-running creator-owned series -- exists partly as a slice-of-life story about a bunch of friends hanging around, and partly as post-Twin Peaks weirdness. Early on one could mistake it for something out of the pen(cil) of Dan Clowes; a scene focusing on various weirdoes inhabiting a city bus has exactly his energy of small town despair touched with quiet menace. It feels of a part with the alternative comics movement of the 1990s (even if it started a bit too late for it). But as the story progresses, it becomes clear that this is pretty much the opposite of what Campbell is doing.

Someone like Clowes, and others of that ilk, stands slightly apart from their characters. Clowes is judging them for their foibles; the city limits of Ghost World form a sort of crucible from which none can escape whole. Wet Moon doesn’t judge its characters, or location, in such a manner. Which is not to say it’s all lovey-dovey niceness; people are shits, often with little grasp of their own existence - it's just that it doesn’t feel like the story itself is pointing at them and laughing. Pretty much everyone who is a name character is part of some scene -- goth, metal, emo -- which demands a certain dress code that makes them stick out like a sore thumb.

You can imagine the type of story that would mock them for this. It feels like most comics stories of that era would see them as somewhat laughable. But look at this page, look at how affectionally the characters are framed, the warmth of touch between Cleo and Trilby in the final panel; the way the sequence builds up from Cleo’s doubt at her new look, the empty black space to the right of the first panel, to the affirmation she receives from her friends, Trilby’s wide smile dominating the second panel.

There is a direct path leading the alt-oddness of Wet Moon to the more mainstream TMNT, a path Campbell walked without ever sacrificing what made her art (both in terms of writing and illustration) what it is. Which makes sense, when the subject of that art is change itself, an arc of constant reinvention and reaffirmation. No matter how much Sophie Campbell's art and writing change and evolve, they still remain fundamentally identifiable, every new form revealing a new facet of what always existed.