This is one of a series of follow-up interviews with each of the four participants in our Fine Art and Cartoonists Roundtable. There are also follow-up interviews with Williams, Watson and Coleman.

“I guess all I mean to say is I think comics are good as kind of a crappy medium.” — Marc Bell

In my conversation with Marc Bell, I was intrigued by his admiration for art that’s “problematic,” that’s “just a little bit wrong.” And he also said, “I don’t know how to explain it,” which brought to mind that famous quote by Georges Braque: “The only valid thing in art is that which cannot be explained.” For me, this gets to the heart of distinguishing what separates outstanding fine art from ... well, from everything else, really.

Bell mentioned a gallery show titled “Krazy.” That’s with a “K,” as in the Kat. Subtitled “The Delirious World of Anime + Comics + Video Games + Art,” it included more than 600 works spread over two floors of the Vancouver Art Gallery in 2008. It was divided into seven sections, each with its own curator. Seth and Art Spiegelman handled comics and graphic novels.

MICHAEL DOOLEY: Does gallery work have an advantage of being more profitable than your comic and illustration work?

MARC BELL: Oh, sure. I mean, I don’t consistently sell work, but it’s good to sell a piece here or there.

DOOLEY: Well, what’s your main source of income, then?

BELL: This is getting real personal. … I’m just joking.

DOOLEY: Well, I know you’ve done dishwashing and DJ-ing. [Laughs.]

BELL: It varies year to year, I guess. If I have a show at a commercial gallery, hopefully, I’ll sell some work. And then maybe I’ll figure out something else for a little while. Like, I’ll apply for a grant from the Canadian government. And I’ve managed to receive one production grant from the Canadian government, which was nice. So it just varies year to year. And more recently, I’ve been trying to get my work out in the commercial-gallery world in Canada. Which has been sort of slow, but I was in a group show in London, Ontario—where I’m from — with several of my London, Ontario, peers like Peter Thompson and Jason McLean and we sold some work. So it just varies year to year, you know.

DOOLEY: Got ya. “Commercial-gallery world,” could you describe that? I’m not sure what that means: commercial galleries as opposed to fine-art galleries?

BELL: Well, in Canada there are artist-run centers that are funded by the government. So if you get a show there, you get a nominal fee — around a thousand bucks. But then the work isn’t really officially for sale; they’re not set up to sell the work. So, I would define a commercial gallery as a private business venture, probably what you would call a “fine-art gallery.” Same thing, I guess.

DOOLEY: Oh, yeah. I see. Just one of the advantages of being a Canadian. [Chuckles.]

BELL: Yeah, I guess so. But I don’t really show at artist-run centers so much.

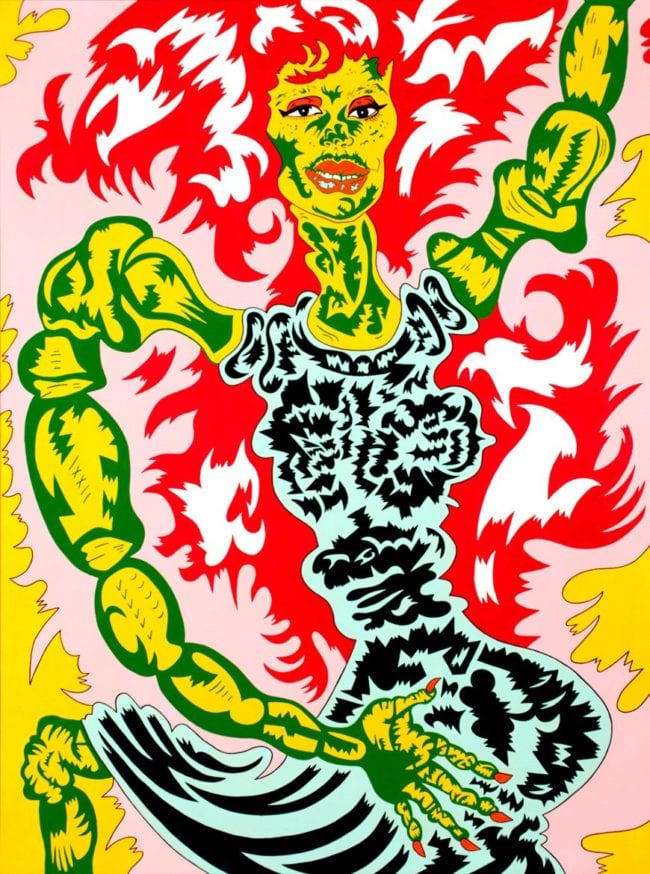

DOOLEY: Who would you consider influential to your development? There’s a bit of the Hairy Who look to some of your work.

BELL: Yeah, I think that was a later influence; I didn’t really look at that stuff till maybe around 2003. My style was mostly solidified by then, I think, but when I finally looked closely at that stuff I knew there was still a lot to try to learn. I grew up in London, Ontario, where there was this group of regional artists that started working in the ’60s: Greg Curnoe and some others. And they had this stubborn point of view like, “OK, we don’t have to go to Toronto to make artwork. We can stay in London, Ontario and make art.” So having them in the background was almost a primer for discovering the Hairy Who cause they were very much Chicago artists who weren’t really part of the New York trends at the time they were operating.

DOOLEY: So it was inspirational for you that they lived outside mainstream cities and were actually making it?

BELL: Yeah, I think I also found the Hairy Who pretty interesting just because their work relates so much to comic books. I mean it’s not comics, obviously, but it seems born out of commercial things like comic books and born out of collecting things. When you’re a fan of comics and weird esoteric stuff, it was easy to discover that Chicago stuff and become a fan of it, whereas who really says, “Oh, I’m a big Jackson Pollack fan.” Doesn’t that seem kind of weird? Do you know what I mean?

DOOLEY: Mm-hmm.

BELL: I dunno. But I could maybe relate to that stuff more as fine art or art or whatever you wanna call it.

DOOLEY: Was there any artist in that group that you felt a particular affinity for or was it the whole package?

BELL: I think it was the whole thing. I guess you get drawn in by [Jim] Nutt or [Karl] Wirsum, but there is so much other stuff.

DOOLEY: So it sounds like you had pretty much developed and solidified your style without any strong influence from the fine-art world.

BELL: I think so. When I first started showing work with Adam Baumgold, he asked me, “Do you know who Jim Nutt is?” Maybe I’d heard of Jim Nutt by that point — I don’t remember — but I don’t think I was too familiar. He’s like, “Do you know who Ray Yoshida is?”

I said, “No.”

“Do you know who Christian Schumann is?”

And I was like, “No …” And then I just started looking at the stuff. Well, Christian Schumann wasn’t part of that Chicago scene, but he was just generally asking about these different artists he thought might interest me. I mean I had already seen Saul Steinberg and stuff like that.

DOOLEY: So Steinberg helped your direction along as well?

BELL: I don’t know. I mean, I looked at him I am sure, but he wasn’t one I really studied at the time. I was definitely familiar with it. But I don’t think I could really say who really influenced me the most. Initially, I was just influenced by comics and that whole world. And I went to art school. So it was just a mixture of seeing art and looking at comics and putting it all into a blender. Like Julie Doucet, I really loved her work. She kind of influenced me and Peter Bagge and all that stuff.

DOOLEY: The comic artists.

BELL: Yeah, the comic artists.

DOOLEY: And it seems like you had kind of a Fort Thunder sensibility even before discovering those guys and Paper Rad and that sort of thing. Is that fairly accurate?

BELL: I guess so. There was a group of people I was working with, in Canada. Not an official art collective like Fort Thunder, but a group that shared things and had a shared sense of humor. It was interesting to see Fort Thunder surface, and the Royal Art Lodge in Winnipeg come up as well. And then to discover, of course, the Hairy Who later, who were also a group. So it was interesting to eventually discover these other groups of people who were sort of working together. But I suppose the people I was working with, we were drawing together quite a bit and ripping each other off so to speak. It was encouraged to steal from each other’s work.

DOOLEY: Yeah. So your influences tended to be the people in the groups around you as you were developing rather than …

BELL: Yeah, I mean those other groups like Fort Thunder and Royal Art Lodge — when I was working with Jason and Peter in the mid-’90s, I wasn’t really that aware of that stuff. We had just kind of developed our own little thing where we would just make these little, photocopied books and mail them around to each other. So it was just this little thing we developed on our own. And then when I became aware of these other things, it just felt familiar to me. And then, of course, seeing that stuff kind of spurs you on to do other things, think about what you’re doing in relation to these other groups of people working.

DOOLEY: And that would hold true of the Kramers crowd and Ganzfeld work as well?

BELL: Yeah, I think so. It was pretty exciting when Kramers 4 was happening cause it seemed like a lot of these things were connecting up.

DOOLEY: “Connecting up,” how do you mean?

BELL: Maybe just for me, well from my point of view … Wait, let me just think about this for a minute. In the ’90s, comics were mainly about stories, but then all this other crazy stuff sort of started to come in. Fort Thunder came along and sort of changed things a bit. Their comics were more eyeball-y and crazy and fantastic than what had been happening. It was a different thing that was still somehow tied to genre.

DOOLEY: Well, their idea of narrative and the comics medium, in general, was more open-ended than what had come before. Would that …

BELL: Maybe open-ended but … Ah, I don’t know. Scratch that. I don’t know what I’m talking about. I’m not a comic historian. I’ll leave that for the academics on The Comics Journal, right?

DOOLEY: [Chuckles.] There ya go. Now, you’ve mentioned that in Canadian art schools, instruction can be really academic and …

BELL: Yeah, but the art school I went to was actually pretty traditional in the art-school sense. There wasn’t that much theory there at all compared to, say, the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, which was nearby and is very much a theory-based school. At one point, in their heyday, they cut all their drawing classes and they were like, “Drawing is dead.” I’m sure I heard that somewhere.

DOOLEY: Hmm. So the kind of training you were getting sounds more like what Robert Williams would prefer, with the importance of craftsmanship, workmanship, that sort of thing?

BELL: I think so, but I was pretty lazy at the time. And there seemed to be a lazy atmosphere at the school in general. I wasn’t engaging much with classes. I was taught oil painting, but I wasn’t really absorbing that. I wasn’t letting myself learn that stuff. I guess I was mainly drawing and I was doing printmaking. I was learning a little bit, but I think school is generally wasted on young people or something. It was wasted on me, anyway. Probably if I was there now or maybe a little earlier than now I’d might’ve gotten more from it.

DOOLEY: Yeah, but when the emphasis is on workmanship to the exclusion or diminishing of creative aspects, doesn’t it become more of a commercial-art school, an illustration training school?

BELL: Oh it definitely was not an illustration school, it was a traditional art school with lots of figure drawing and painting and printmaking and sculpture where you actually do a bronze pour. So it wasn’t really so much about illustration at all. It’s not the kind of school where there’d even be an illustration course. Like it was very much a bare-bones, traditional fine-arts school. For example, I wasn’t showing any comics. I made a decision: I said to myself, “I’m not going to show any comics to the professors; it just doesn’t make a whole lot of sense.”

DOOLEY: Yeah [chuckles]. So those students who were applying themselves, what kind of field would they go into after they left school?

BELL: I dunno. To tell you the truth, I don’t think very many of them still make art. I was saying it wasn’t conceptual or academic at all but when I was there I think there was a bit of a transition going on. Like a friend of mine who was there was doing pretty funny, more challenging kind of work. Minimal art, but pretty funny … sort of conceptual one-liners. There was a bit of divide in the faculty at that point and it all came out in one of his crits. And I think some newer people have come in who might be a little more invested in art theory and newer kind of practices, like media and multimedia or whatever you wanna call that stuff.

DOOLEY: From your current perspective, do you see any use in that newer kind of education?

BELL: Which kind? What do they call it? Do you know the terms? There’s all these different terms. Like “Relational Aesthetics.” There’s all these different terms for this newer kind of art. Relational Aesthetics. Have you heard that one?

DOOLEY: Uh, that sounds good. [Chuckles.] What does it mean?

BELL: Well again, I’m no comic historian and I’m no art theorist, but relational aesthetics are less about, like you say, illustration or making a picture. They’re more about an idea. Like, having a dinner party can be art. So I guess they probably relate to conceptual art. But if you’re going to art school and you wanted to be big in the art world, that kind of teaching would probably be good for you because a lot of art that is accepted these days is about relational aesthetics or conceptual theory or art theory. At least in Canada, that is the case. But it wouldn’t be that useful for someone like me who’s maybe just more interested in making pictures, you know?

DOOLEY: Yeah. So, that kind of work is more accepted in the fine-art world than what you’re doing now?

BELL: Well, but then the other thing is the art world is so fragmented because you have all these different little worlds going on. It seems like the art theorists were running the art world for a long time, but now things are a little more mixed up. More traditional painting and drawing seem to be coming back a bit. So it seems like there’s several things going on right now.

DOOLEY: Well, perhaps more important than defining what constitutes fine art is what constitutes quality fine art, what constitutes art that is good enough to sustain itself over the years, decades, centuries.

BELL: Yeah, I don’t know if that’s for me to say, really. But I think, you know that guy Dave Hickey?

DOOLEY: Yeah. The Vegas art critic, writer.

BELL: Yeah I was watching some of his talks on YouTube and he was talking about how the people eventually decide what will be remembered. You can contrive these things … I mean it’s hard to say, really. I guess some stuff gets to a point where it’s just kind of undeniable as art. I don’t know what I can say about the specific aesthetics that make up a great work of art. I just don’t know if I have the vocabulary to describe it. I can’t really make that judgment call. I just have no idea.

DOOLEY: OK. Well, let’s personalize, then. [Chuckles.]

BELL: OK. Well, I remember in art school I had this painting teacher and we were talking about painting and I said, “Oh, you know, I think that the art that will be remembered from right now will probably be stuff like The Simpsons.” I said that and she was kind of offended by that. But I was just trying to suggest that stuff that is very popular right now will certainly be remembered kind of as art, you know, in the future.

DOOLEY: Hmm.

BELL: Does that sound strange?

DOOLEY: Yes it does. [Chuckles.] And why were you saying that? Why were you thinking that The Simpsons, which is in the popular arts category …

BELL: Just because it is an undeniable, kind of cultural force in some way. I mean, maybe it varies. But I think something like that is so iconic it will be remembered. In fact, in L.A. here, I just went to see this great show of Aztec art. And you look at these vases and they’re so cartoony and crazy, some of the designs on the pottery look like The Simpsons. You know what I mean. You could put The Simpsons next to it and go, “Oh, OK.” You could string those together.

DOOLEY: OK. And so inasmuch as this Aztec art continues to reveal itself over time, you could say that fine art would allow each new generation to discover different aspects that are meaningful for them?

BELL: Yeah. I guess art these days is such a personal thing or people look at the general idea of it, “Oh, art’s really personal.” But if you look at the bigger picture you could also look at art as a…ah never mind. See, I start something and I can never finish it.

DOOLEY: There have been more major comics exhibitions getting into respectable museums and galleries since then. Have you seen any of the big shows?

BELL: I saw one in Vancouver. I think Seth and Art Spiegelman curated it. It was called Crazy.

DOOLEY: And how was that for you?

BELL: Well, I was living in Vancouver at the time, so I was a little bummed I wasn’t included. I’m just kidding. [Chuckles.]

BELL: It was interesting to see some of those originals. But the funny thing about comics is that they are meant for reproduction, you don’t really need to see the original. I guess the funny thing is showing comics on the wall is that it’s immediately historical. Because when you’re making a painting, you’re intending for that painting to go on the wall in a gallery. If I am some hot-shot painter and I have a brand new show, I’m making that painting to be on view at the opening. When I’m a cartoonist, I’m making the comics to be in a book. I’m not making comics to show them on the wall. So when I put my comic page on the wall, it’s immediately a historical artifact even if it was done last week, because the first intention was for it to be in a book. That line’s blurred, of course, when you have so-called art comics or whatever ’cause they can sometimes provide both functions. You could make some crazy thing for a book that maybe isn’t the greatest read or is kind of a crazy read, but then you could also put it on the wall and it can hold up as art. I’m not saying comics aren’t art at all. I’m just saying the art of comics is intended to be on the page of a book.

DOOLEY: Yeah, and it becomes an artifact when it’s put in galleries.

BELL: Yeah, of course.

DOOLEY: So, if you were considering The Simpsons as art then would the artifacts be the cells or the storyboards …? [Chuckles.]

BELL: Yeah, I know. I was being cheeky when I was talking to my professor. I was just sort of suggesting that the art of today … what might be remembered people might not be thinking right now as official Art with a capital A. If you look at old, historical artifacts and things like that, those probably weren’t considered art of the day. I suppose they were religious objects and … I mean if you look at that old Aztec art I don’t think they were thinking, “Oh I’m a great artist. I’m gonna put some great personal art on the wall about my feelings and everyone’s gonna love it and it will be in an art-history book.” It was more of a thing people did to entertain or provide a function. All I’m saying is people might be just overlooking a bit the stuff that actually might be remembered. They might not be looking at it as art right now, necessarily.

DOOLEY: Yeah.

BELL: I feel like I’ve talked about that idea too much. It’s just like a vague bratty notion I had in university when I was 21.

DOOLEY: Those late-night dorm-room discussions, huh? [Laughter.]

DOOLEY: Now, if you look at 1960s work in most of today’s art-history books, the same artists that were considered important and shown in the museums 50 years ago are still maintaining themselves.

BELL: Oh, you’re exactly right, but maybe we’ll have to go in a time machine to look at art-history books in a hundred years and then we’ll see a big picture of Bart Simpson in there [Laughter.] It goes back to what I was saying before: I have no idea what’s going to be remembered from this time right now. Maybe we will only remember retrospectives of New York artists from the ’50s and ’60s that happened in the 2000s. I have no idea. But it will probably be remembered as an overblown time of excess and the overblown art market, the time of Damien Hirst. He is a great example of the time right now I think.

DOOLEY: Well, that’s one of the ways that Andy Warhol made his way into the history books as well.

BELL: Exactly.

DOOLEY: You’d mentioned appreciating things that are confused, usually work that had some problems. Could you talk more about that?

BELL: I usually like stuff that is a little problematic, like outsider art, and weird stuff. I don’t know how to explain it, but I kind of get a kick out of stuff that’s just a little bit wrong. So it’s not all crystal clear.

DOOLEY: Yeah. And that’s something you work at in your own art?

BELL: Yeah, I think so. Well, I don’t know if I work at it or that’s just how it works out. There’s just usually something wrong with it.

Transcribed by Ben Horak and Anna Pederson and Janice Lee