He had a theory that if you should find one perfect thing, or place, or person, you should stick to it. Do you think that's very silly?

Not at all. I’m a firm believer in that myself.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940)

The seminal American comic-strip character the Yellow Kid always wore a yellow shirt so long it nearly touched the ground. Donald Duck caused endless amounts of mischief in a bowtie-adorned sailor’s top (and no bottom). Charlie Brown eternally sulked around his neighborhood in a zigzag t-shirt. The spirited Little Lulu forever sported a red dress, and her sidekick Tubby favored a black jacket and brown shorts combo:

(Was each character’s closet filled with dozens of the same outfit?) Alfred Hitchcock shared the sartorial obsessiveness of these and countless other comic-strip characters. According to his long-time collaborator Norman Lloyd, the director regularly wore one of twenty-eight identical suits (the jackets and pants were numbered “for dry-cleaning purposes”). This fixation says something profound about Hitchcock’s psychology as well as that of classic cartoon characters, who seem doomed to live in a steady-state of repetition, trapped in an endless series of sets-ups and punch-lines.

(Was each character’s closet filled with dozens of the same outfit?) Alfred Hitchcock shared the sartorial obsessiveness of these and countless other comic-strip characters. According to his long-time collaborator Norman Lloyd, the director regularly wore one of twenty-eight identical suits (the jackets and pants were numbered “for dry-cleaning purposes”). This fixation says something profound about Hitchcock’s psychology as well as that of classic cartoon characters, who seem doomed to live in a steady-state of repetition, trapped in an endless series of sets-ups and punch-lines.

In Sir Alfred #3, cartoonist Tim Hensley turns Hitchcock’s life into sixty-five comic strips, most of which employ the look of Little Lulu comic books. Like Lulu’s pal Tubby, Hensley’s young Fred wears a jacket and shorts, and his adult Alfred sticks to a black suit. It seems natural, almost inevitable, that Hitchcock should receive the kind of ‘cartoon treatment’ that Hensley gives him since he had already given it to himself. Like so many single-outfit comic-strip protagonists, he inhabits a world of jokes and pranks. Perhaps the perfect expression of his cartoony self-presentation appears in the gag that opens the Alfred Hitchcock Presents TV show. As the director strolls across the frame, reality and cartoon merge as Hitchcock’s profile aligns with a drawing of his profile:

Hensley finds in Tubby, a character with a portly silhouette, a more than suitable model for the director:

One of Hitchcock’s actors described the filmmaker as a kind of stunted Tubby, “an overgrown schoolboy who never grew up and lived in his own special fantasy world.”

In the oversized, beautifully printed Sir Alfred #3, the cartoonist eschews orthodoxies of biography: he ignores chronology, omits milestones in the subject’s life, and even draws moments when young and old versions of the protagonist meet. By labelling the comic “#3,” Hensley alerts us that he’s not following the conventional order of things. (Note to collectors: #1 and #2 don’t exist.) On the book’s cover, the phrase “Apocryphal anecdotes biographically gleaned!” cryptically hints at Hensley’s comic-strip strategy: though relying on incidents from Hitchcock’s life, the cartoonist restages each by employing the look, rhythm, and exaggeration of classic funny-book cartooning. Hensley treats fidelity on a sliding scale, from strips that play it relatively straight to those that expand, compress, or combine incidents into an effect we could call “oblique biography.” Though the strips take different tactics, Sir Alfred #3 consistently amplifies the comedy and perversion of the director’s life. Hensley’s Hitchcock is equal parts punster, prankster, and predator.

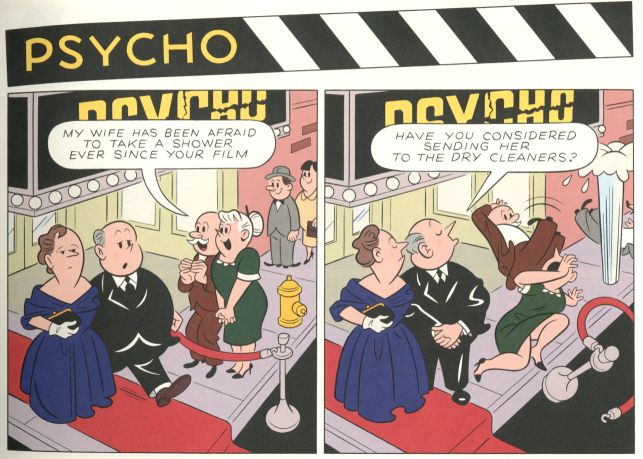

To better understand Sir Alfred’s method, it’s best to look at some examples. In 1960, Hitchcock received a letter from a man whose daughter had recently seen Psycho. Unnerved by its infamous shower scene, she refused to bathe for weeks. Hitchcock wrote back, dryly suggesting they try a different hygienic approach: dry-cleaning. Hensley cartoons the exchange as a conversation outside of a movie theater and replaces the father and daughter with a husband and wife:

The strip turns Hitchcock’s wry comment into an over-the-top gag by using a classic comic-strip device: the “plop take.” The force of the joke is so strong — the power of wit made physical — that it knocks characters off their feet. Always pushing cartooning to new heights of pointed absurdity, Hensley allows an inanimate object to get in on the action. Confronted by the director’s waggishness, a fire hydrant literally blows its top.

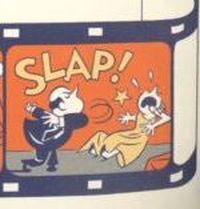

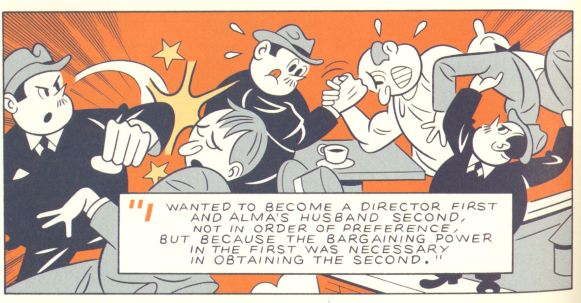

Hensley gives a decidedly unfunny Hitchcock anecdote a different kind of comic-strip treatment by looking to the medium’s — and the director’s — intimate association with violence. In Rebecca, Joan Fontaine plays a naive, insecure, and very weepy second wife. She’s dominated by and lives in fear of her husband — just as Fontaine feared her demanding director: “He wanted total control over me,” Fontaine said of Hitchcock, who recounted a moment when the young actress told him she couldn’t cry anymore: “I asked her what it would take to make her resume crying . . . She said, ‘Well, maybe if you slapped me.’ I did, and she instantly started bawling.”

To cartoon this troubling moment (and many others), Hensley uses a familiar, and appropriate, comic-strip format: the four-panel gag strip. Throughout its history, the daily newspaper strip has been driven by violence as much as by comedy (frequently the two are indistinguishable). Such strips often end with a literal “punch” line, just as this one closes with a violent “slap take.” Though Hensley’s version of the scene stays close to the truth, the cartoonist visually reveals what the historical record leaves out: how Hitchcock must have felt during this exchange. Hensley shows Hitchcock’s glee at the invitation to violence, his satisfaction at sadistically slapping a woman in the service of his art. To convey the director’s inflated sense of masculine bravado, the cartoonist uses the Lulu style to conjure the posture of an arrogant theatrical bullfighter who has just bested a wounded opponent:

In Sir Alfred, cartoon worlds continually collide — it’s as if a violent comic-strip troublemaker like the drunken Andy Capp suddenly invaded the wholesome neighborhood of Family Circus.

In Sir Alfred, cartoon worlds continually collide — it’s as if a violent comic-strip troublemaker like the drunken Andy Capp suddenly invaded the wholesome neighborhood of Family Circus.

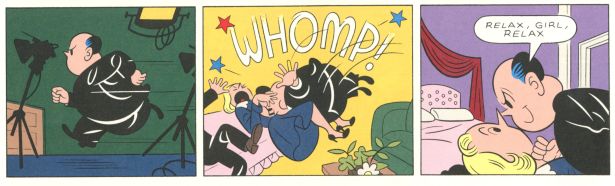

Hitchcock, too, liked to cause a little trouble. When riding an elevator, he’d sometimes tell what he called an “elevator story,” a made-up gory tale intended to horrify a captive audience of fellow riders, becoming more shocking with each passing floor. Hensley recounts this habit in a one-page strip (here are its last four panels):

In an untitled one-page strip from Little Lulu — we could call it “The Birds” — Lulu, acting like a little Hitchcock, pranks an unsuspecting group of men on a park bench (here are its last four panels):

In both comics, tension builds throughout the set-up panels, things erupt in the penultimate panel (mouths open and bodies contort as people scream and flee), and then, in the final panel, the pranksters serenely enjoy their success, with eyes closed, hands folded, and a smug look of satisfaction:

Sometimes, the rhythm of comic-strip pranks and real-life antics align.

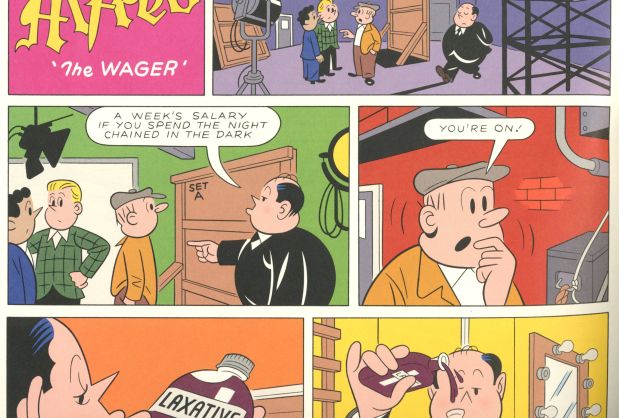

As evinced by his inspired blending of Hitchcock’s life and Little Lulu comics, Hensley’s genius is highly synthetic: Sir Alfred juxtaposes an odd collection of styles, disconcerting emotional effects, and a wide range of comic-strip formats and techniques. Perhaps the best example of this ability appears in the collection’s least biographical comic: the introduction to an imaginary episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents (each began with Hitchcock dryly commenting on the week’s story). The strip ties together several artistic forms (film, storyboarding, graphic novels, gag panel cartooning, comic books, biography), specific works (DC’s comic The Adventures of Bob Hope, Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much and The Wrong Man), all while commenting on Sir Alfred’s concerns: biography and truth; narrative manipulation and suspense; the connection between a joke’s rhythm and sexual release; etc. As if that’s not enough, Hensley weaves in a few sound-related puns, one on the word “note” and another based on an allusion to film history: when Bob Hope presses Hitchcock’s doorbell, it goes “BING” — Bing Crosby starred with Hope in several famous “road movies.” (In Hensley’s strip, Hope’s trombone playing recalls a trombone comedy bit in Hope and Crosby’s “Road to Bali.”)

Though the strip connects film and comic storytelling, as if to remind us to avoid facile conclusions about the mediums’ relationship (e.g. the often-heard “comics are just movies on paper!”), Hensley concludes by breaking the fourth wall and embedding several panels within a panel in a very comic-book-y, which is to say, un-filmic way. The strip is dense, funny, and clever, but its meta-commentary on the comic’s themes, like Sir Alfred itself, is elliptical. The strip highlights Hensley’s process and his ‘creed’: to privilege play and absurdity, and to disturb and disorient (and entertain) readers. Although this one-page comic uses factual material (such as lines from the director’s interviews), Hensley’s allegiance here and throughout Sir Alfred is clear: Art over Truth.

**

One way to understand the outré nature of Hensley’s Hitchcock (which is to better understand Hitchcock’s Hitchcock), is to return to clothing. In most traditional comic strips, clothing folds are indicated by black lines, but since Tubby’s jacket is already black, folds wouldn’t be visible. The jacket is, however, marked with thin white lines that unobtrusively indicate the sleeves’ outlines:

In Hensley’s comic, Tubby’s white lines become, when applied to Sir Alfred’s black suit, something beyond functional, something otherworldly and wholly un-Lulu. With their beautiful, calligraphy-like gestures, the exaggerated folds — which Hensley delineates with hundreds of patterns — suggest mysterious symbols in a hieroglyphic system:

Though other characters wear black, Hensley saves this elaborate marking strategy for Hitchcock, who, as a result, becomes a visual anomaly in his own story, a fascinating, dangerous, and almost unknowable ‘character’ in a world of ordinary people.

Though other characters wear black, Hensley saves this elaborate marking strategy for Hitchcock, who, as a result, becomes a visual anomaly in his own story, a fascinating, dangerous, and almost unknowable ‘character’ in a world of ordinary people.

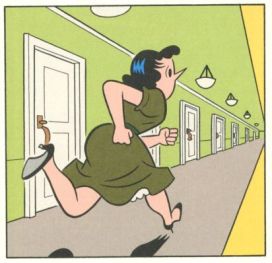

Sir Alfred also stylistically deviates from Little Lulu in terms of a key element of comics form: a panel’s ‘point of view.’ While its predecessor relies on unobtrusively staged panels, Hensley judiciously invokes a noir-inflected set of angles:

Yet even when Sir Alfred is at its most Little Lulu (and least Hitchcockian) there’s always something odd about it — and I often can’t locate the source of this strangeness. Is it the result of placing peculiar panel angles side by side? Is it an image’s use of a slightly off perspective? Is it the inevitable weirdness that comes from juxtaposing Tubby’s chaste cuteness with Hitchcock’s punning perversion?

Yet even when Sir Alfred is at its most Little Lulu (and least Hitchcockian) there’s always something odd about it — and I often can’t locate the source of this strangeness. Is it the result of placing peculiar panel angles side by side? Is it an image’s use of a slightly off perspective? Is it the inevitable weirdness that comes from juxtaposing Tubby’s chaste cuteness with Hitchcock’s punning perversion?

Maybe Sir Alfred’s peculiarity stems from the weird goings-on in the panels’ backgrounds. Hitchcock said that directors need to know “how to sketch a décor” and Hensley masterfully, and eccentrically, composes each set and its furnishings. Important features (like floors and walls) might not be indicated or they might disappear and reappear from panel to panel. And the picture frames in Hitchcock’s office almost always contain psychologically suggestive ink-blot artwork (sometimes it disappears and reappears, too). In comics, picture frames and their contents often seem like analogues for panels and their imagery, and Hensley exploits this curious association.

I certainly didn’t notice these kinds of things until I’d read the comic several times, suggesting that that they might have had an unrecognized influence on me. What else am I missing? (Is there some form of subliminal surrealism at work here?)

I certainly didn’t notice these kinds of things until I’d read the comic several times, suggesting that that they might have had an unrecognized influence on me. What else am I missing? (Is there some form of subliminal surrealism at work here?)

Though sources of the comic’s strangeness often elude me, I’m sure of this: as in Hensley’s masterful 2010 graphic novel Wally Gropius, Sir Alfred’s level of craft is absurd. Each of the comic’s panels, like each of its strips, is a beautiful composition, defined by meticulous and controlled drawings. I can only think of three or four cartoonists who routinely create so many perfect images, and even fewer whose art shares Hensley’s uncanny mix of the peculiar and the precise:

To color these unusual images, the cartoonist often uses an expanded version of the flat palette of mid-twentieth-century comics. Yet Hensley’s choices — especially the shades he selects for consecutive panels’ backgrounds — look decidedly modern without bearing the slightest resemblance to the over-colored confusion of so many current comics:

Like its coloring, the comic’s hand lettering — a cartooning skill in rapid decline — is astonishing, at the level of mastery found in comics by Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware. Hitchcock began his film career as an intertitle letterer, and Hensley, in addition to perfectly recreating the look of silent-film intertitles,

uses dozens of font styles (all hand-drawn, of course) for his strips’ “display lettering.” (He also reimagines, in elegant and sparse calligraphy, a number of film logos, such as one for Smokey and the Bandit (a film that Hitchcock, surprisingly, watched repeatedly). In a way that’s almost only possible when a cartoonist letters his own comics, Sir Alfred’s text and art connect organically. The shape and feel of Hensley’s lettering surfaces in all of the cursive-like fold lines he draws (or letters) on Hitchcock’s suits.

**

Film critics will forever argue if “auteur theory” is useful when talking about directors like Hitchcock. But in comics, there’s a method of working in which the author’s vision inarguably dominates a comic’s every element: the solo cartoonist. The auteur case makes itself for Sir Alfred #3: Hensley is its writer, director, cinematographer, art director, lighting director, costume designer, prop person, location scout, casting director, cast, editor, Foley artist, etc. . . . He performs all of these tasks with an acute awareness of each one’s role in generating emotional effects in the audience (à la Hitchcock) and with a mastery rarely seen in the world of contemporary comics.

Unless a cartoon auteur operates his or her own printing press, there’s an unavoidable, and risky, collaboration that awaits. After the artwork is finished, the cartoonist surrenders the work to a printer and hopes for the best. Hensley found the perfect collaborator in Alvin Buenaventura. Alvin’s final work, Sir Alfred #3 was published by his Pigeon Press, and he carefully oversaw every aspect of its manufacture and printing. In a recent remembrance, Hensley recalls Alvin’s pursuit of what Joan Fontaine’s character in Rebecca calls the “perfect thing”:

The photos you see of him looking through a loupe on press are indicative of his focus. I asked him about the loupe, and he said it had filters so you could look at just cyan, magenta, or yellow at a high magnification. I never knew anyone could do that or be willing to. If you look at even his most low-key books, you will see that kind of attention to the simple matter of the plate hitting the paper. Because the size of my book meant the pages could not be ganged together, he did twenty-two press checks. Who does that? I wouldn’t have.

Sir Alfred #3 documents an alliance between two meticulous artists. If you look closely, in nearly every panel of the full-color strips, Hitchcock blushes. At times, this effect is so subtle that it borders on invisible. Both minor (the mark is always small) yet significant (it appears hundreds of times), it’s the perfect index of Hitchcock’s ceaseless sexual arousal (and perhaps the corresponding guilt that, though unspoken, his body can’t hide). As the kind of coloring that could easily be ruined by careless printing, it’s also a sign of Hensley’s painstaking attention and Alvin’s masterful production. Alvin knew that if each color did not fully saturate the page, effects like the blush would be compromised.

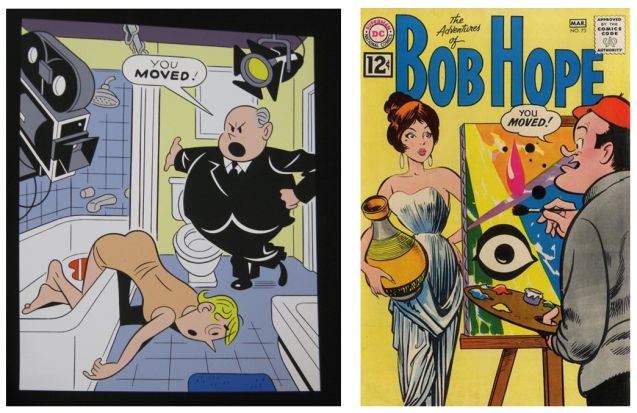

In the tradition of Alvin’s artistic generosity, Sir Alfred #3 is more than just a comic: it’s a collection. It comes with a giclée print of a disconcerting scene from the filming of Psycho as well as a hand-printed letterpress coaster (a nod to Hitchcock’s late alcoholism and food-and-drink related pranks). It’s all packaged in a custom-made Mylar sleeve with stickers that feature gags done especially for the container. I mention the custom aspect not because it’s the kind of detail that excites comics nerds, but because it gets at a truth about Alvin. Like Sir Alfred #3’s unusual dimensions (nearly twice the size of a regular comic), everything Alvin did was literally non-standard. For him, the pursuit of artfulness involved finding new — which inevitably meant difficult, laborious, and expensive — ways to do things. It was never about making money, or even “breaking even.” It would have been far cheaper to manufacture the comic overseas, but Alvin chose a local printer so he could monitor the comic’s progress — with an absurd number of press checks.

The history of American comics is littered with great work that’s been poorly produced and printed. Few cartoon auteurs are lucky enough to find a partner who takes an “art at any cost” approach. Alvin filled that role for the artists he worked with, and his dedication is nowhere more visible than on every page of Hensley’s comic. Sir Alfred #3 stands as an oversized, full-color, and never-to-be reprinted testament to the aesthetic brilliance of Alvin Buenaventura and the cartooning genius of Tim Hensley. I can say, without exaggeration, that their collaboration produced a “perfect thing.”

____________________________________________________________

BONUS: Comics within Comics!

Hensley models Sir Alfred’s cover lettering and design on early issues of DC’s The Adventures of Bob Hope comic books:

For the Psycho giclée print, Hensley blends a reworked historical incident with a gag from a Bob Hope cover. In reality, it was Hitchcock’s wife Alma who, when watching an edit of the movie, saw that Janet Leigh had moved slightly when she was supposed to be dead:

In a weird take on the Hitchcock cameo, characters like Archie’s Betty and Veronica and Family Circus characters pop up:

In the only Sir Alfred strip to focus on a film and not the director’s life, Hensley blends the Little Lulu style with the pantomime of cartoonist Milt Gross’s “I Won’t Say a Word About” comical takes on ‘serious literature.’ Gross ‘reviewed’ Daphne du Maurier’s novel Rebecca in this cartoony way (the novel was the basis for Hitchcock’s film.) And Hensley takes on Hitchcock’s I Confess:

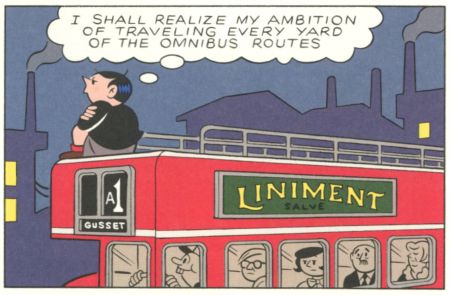

One of the sleeve's stickers features a very Tubby-type gag:

____________________________________________________________

Ken Parille is editor of The Daniel Clowes Reader: A Critical Edition of Ghost World and Other Stories. He teaches at East Carolina University and his writing has appeared in The Best American Comics Criticism, The Believer, Nathaniel Hawthorne Review, Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, Comic Art, Boston Review, and elsewhere.