Lee Holley, who assisted on Dennis the Menace and subsequently created an idyllic picture of postwar American teenage life through his Ponytail syndicated daily cartoon panel, died on March 26 in a plane crash in Marina, California. He was 85.

Holley, an amateur pilot, was flying his single-engine plane when it crashed at Marina’s municipal airport on the morning of the 26th, reported Matthew Sedacca at The New York Times. There were no passengers aboard. Marina is about ten miles north of Monterey, where Holley lived.

Gordon Leroy Holley was born in Phoenix on April 20, 1932, but grew up, with a brother and sister, in Watsonville, California. Lee showed artistic talent from a young age. In high school he began taking on commissioned work and painted wall murals for local businesses.

“Word got around that I did this, and one of the main themes featured teenagers,” he told Mark Arnold in Pocket Full of Dennis the Menace. (All subsequent direct quoting of Holley is from Arnold unless otherwise noted.)

In his junior year, a man came into his art class and offered him $100 to paint a wall in a former smoke shop that the man was converting to a teenage “hamburger hangout with a jukebox” and ice cream. Holley took the job and spent a couple months painting murals of high school activities—“cars, football, basketball, sharing a milkshake with two straws—you name it. It caught on. The kids loved it. It gave me some identity and the stores next door hired me to do similar things,” Lee finished.

Just as he graduated from high school in June 1950, the Korean War started, and Holley enlisted in the Navy in 1951 and was stationed on an aircraft carrier as a weapons inspector.

“I spent two tours off the coast of North Korea near the bombs and rockets and all that. In my spare time, I continued to draw cartoons,” eventually being published in Our Navy and All Hands. He created a nautical character called Seaman Deuce after the lowest enlisted rating in the service.

UPON RELEASE FROM THE NAVY, Holley took advantage of the GI bill and enrolled in famed Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles and was later hired by Warner Bros Studios. Although he aspired to do a comic strip, doing animation was a great experience.

“I was surrounded for the first time with people who were professional artists and cartoonists,” Holley remembered. “I was working with the most talented people in the animation business, and it was a fun environment. I was an in-betweener for a couple of months when they moved me into Friz Freleng’s [award-winning] unit as assistant to Virgil Ross. Neat guy. He was a great animator, very quiet and low key. Virgil worked real rough, and my job was to clean it up. I worked hard at it for years. The animators from that era really couldn’t draw well, but they could animate like gangbusters.”

For Chuck Jones, he worked on “What’s Opera, Doc?” in which Elmer Fudd is singing “Kill the wabbit!”

“I later found out that Chuck asked for me and another fellow to help because we could draw so well.”

Over four years, Holley worked on three cartoons that won Academy Awards—one with Yosemite Sam, another with Sylvester and Tweety, and another with Speedy Gonzales.

Holley moved up from assistant animator to a ‘B’ animator and got small scenes to animate. “It was really great training,” he said, “but I persisted in dreaming about a comic strip.”

And he kept working in off hours on the characters he’d drawn as a teenager—teenage boys, girls, cars, boyfriends, football—“the whole nine yards.”

Another cartoonist at Warners saw his efforts and urged him to show his work to Hank Ketcham. As Holley told Arnold, he drove up to Ketcham’s ranch in Carmel Valley. Ketcham immediately found out Holley had been in the Navy; and he knew Holley was in animation. Ketcham had done both. A kinship was immediately established, and before the interview was over, Ketcham gave Holley a three-day try-out.

At the end of the three days, Ketcham extended the try-out period and soon hired Holley.

“I like your work,” Ketcham said, “—you’re going to be my assistant.”

He put Holley to work on the Sunday Dennis the Menace. Al Wiseman, who had been doing the Sunday Dennis, moved on to the Dennis comic book.

“Nobody touches the daily,” Ketcham told Holley. “The reason that I’m having the Sunday page done by somebody else is that the daily panel is the heart and soul of Dennis the Menace. That’s where the money is. ... The Sunday is created as a great supplement, but I prefer the daily.”

KETCHAM WAS A LEGENDARY EXACTING TASK MASTER. Holley’s cubicle was on the other side of a half-wall that separated him from Ketcham, and Ketcham was always looking over his shoulder, making suggestions and sometimes brutally critiquing Holley work.

But Ketcham liked Holley. In a 2005 autobiography, Ketcham described Holley as a “young fitness nut and a clever cartoonist with a special affinity for the younger generation.”

Holley was soon relieved of the pressure of working directly under Ketcham’s eye: Ketcham moved to Europe where he stayed for most of Holley’s stint on the strip. And Holley did all sorts of promotional work in connection with the Dennis tv show, just then getting started— Kellogg’s cereal box illustrations and Little Golden Books artwork. But he still dreamed of doing his own comic strip.

Working in his spare time on a comic strip concept, Holley had taken a friend’s suggestion and turned his teenage comic strip hero into a ponytailed heroine. He’d been moonlighting gag cartoons for Teen magazine, and he often drew a teenage girl character with a ponytail. “The reason for the ponytail,” Holley explained, “was to make her a little more distinctive than the other kids.”

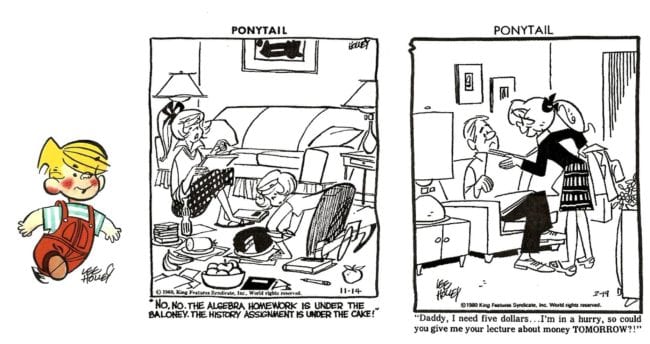

As Sedacca put it: in his new cartoon idea, “Holley depicted a lanky teenage girl immersed in postwar suburban life: cruising in hot rods to drive-in movie theaters and burger joints, attending school football games, negotiating with teachers at Watson Hill High School (about completing her homework), and managing diplomatic concerns with her parents (like the size of her allowance).”

And he had taken Ketcham’s advice: “Why draw four or five panels when you can say it all in one?”

In his panel cartoon, Holley’s line is crisp and clean, his compositions casual—simply drawn but full of telling visual details with solid blacks lending accents—and his figures are supple and lively. There’s a Ketcham quality to Ponytail (as Holley christened the panel), but Holley had boiled it down and condensed it.

Without telling Ketcham (who was in Switzerland) about it, Holley submitted his Ponytail panel cartoon for syndication, and King Features took it. It started November 7, 1960.

When he finally told Ketcham, Holley said to Arnold, it was when they met for drinks at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco on one of Ketcham’s trips to the States. “He was very pleased for me,” Holley remembered. “Very generous and kind, and told me I was with a great outfit. He wished me a lot of luck and said I was going to make a million dollars. He said I could even go on doing the Dennis Sunday page, and if I cold maintain the quality, the job was still mine.”

So Holley continued until late 1961 when King wanted him to do a Sunday version of Ponytail in comic strip form. He was soon overwhelmed. And Ketcham knew it, said Holley. So they parted ways.

Years later, Ketcham said: “Lee was a really neat guy. I felt he quit me too early. I wanted to train him a little bit more. But he sold Ponytail and it went okay.”

Holley had done the Sunday Dennis for four years, 1958-1962. The Sunday Ponytail was launched January 7, 1962.

MANY OF PONYTAIL’S NARRATIVES revolved around dating, with her focus on her main beau, Donald Dawson. By high school hallway lockers she tells him: “Of course I’ll love you forever, Donald. … Well, at least until someone with a better car comes along!”

Newspapers liked Ponytail because it attracted younger readers, Greg Beda, who is writing a biography of Holley, said in a phone interview with Sedacca.

Although Emmy Lou and Penny predated Ponytail in focusing on American teenagers, Holley’s dialogue was often considered the most authentic.

In 1963, Arnold writes, Holley revealed on the television game show To Tell the Truth that he conducted field research by chatting up teenagers at pizza parlors and attending dances. He subscribed to publications like Teen Beat and Seventeen and even went back to his own high school to sit in on classes, he told John Province in an interview in Hogan’s Alley, quoted by Arnold. He also wove his own family members into the story lines.

“Ponytail’s boyfriend, Donald, was our brother Donald; Ponytail’s father was like our dad,” his sister, Donna Roberts, said in an interview. “He drew on those memories.”

Ponytail wasn’t Holley’s only work. He continued moonlighting. He drew characters for Gold Key Comics’ Looney Tunes and Porky Pig books during the 1970s, and succeeded Greg Walker in drawing the Bugs Bunny newspaper comic from 1980 to 1988.

By 1988, the number of newspapers still publishing Ponytail had dwindled.

“These things have a life to them,” Holley said to Arnold. “They build, reach a peak, and eventually peter out. I realized I wasn’t doing an Archie that was going to outlive its creator. I had about 300 papers for most of the run, and I learned that panel cartoons didn’t stay fixed the way strips did. They float around and appear in different places in the newspaper, and that’s how you lose your readership.

“Bill Yates [King’s comics editor] phoned me,” Holly continued. “He was very nice but said, ‘Lee, I’ve been looking at the client list, and it’s not what it once was. How are you fixed?’

“I knew it was coming and said, ‘Bill, there’s nothing you need to be concerned about. If you want to pull the plug, it’s okay with me.’”

Holly had invested widely and very successfully in real estate. He told Arnold his income from Ponytail was down to around $20,000 a year, but he “didn’t need a dime of it. The cartoon didn’t take much time, so I’d just kept doing it.”

Yates pulled the plug, and Ponytail ended with the October 15, 1988 release.

What Holley enjoyed most about his career was the freedom it gave him, he told Province.

“There was no one telling me what to do,” he said. “I had deadlines, but other than that I was on my own. It really wasn’t work to me.”

In addition to his career and love of drawing, the Monterey Herald’s obit noted, Holley had a passion for flying. He loved to fly his own plane, and enjoyed flying over the Monterey Bay. One of his favorite experiences was renting a plane in New Zealand and flying from the North Island to South Island.

Holley was also an avid runner. He ran over fifty marathons, including ten Boston Marathons. In addition to running, Lee loved playing tennis, and would spend hours on the courts whether at Seascape or the Palm Springs Tennis Club. Lee also enjoyed traveling and was ardent reader, especially anything pertaining to WWII history.

Lee truly enjoyed life, the Herald said, and enjoyed making others happy. He took great pleasure in doing sketches for anyone who asked, whether it was for single person or for a class full of children.

In addition to Matthew Sedacca’s report in the New York Times and an obit in the Monterey Herald, I’ve relied for this fond farewell mostly upon Holley’s own words, recorded in Pocket Full of Dennis the Menace by Mark Arnold (pp. 64-78).