Your reward for [art] ... is ... what gives you a kick.

—Maxon Crumb

In 1999, I interviewed and wrote about Maxon Crumb (“Alone in the Western World,” The Comics Journal #217, November 1999, reprinted in Levin, Outlaws, Rebels...). He was, I still say, the strangest person I ever met. When I was asked to review Malcolm Whyte’s illustrated biography of Maxon1, Art Out of Chaos (F.U. Press. 2018), I said I would if I could interview him again. We’d had no contact since he’d come to a reading of mine for Outlaws, and I wondered how time had treated him. (I knew it had changed me, and I wondered if that those changes included my characterological assessment.) But Whyte said Maxon no longer communicated with him and could be contacted only through a nephew in Colorado. I emailed the nephew but did not hear from Maxon.

I decided to review the book anyway. The rhythm of daily writing had become important to my days and this seemed an interesting beat to add.

i.

white vans stream through unforecast rain; hopefully dry-keeping

umbrellas tread below UC building overhang, undissuadedMark said “She’s no Robert Stone. But she’s no Robert Ludlum.”

A woman said, “A bunch of these moms I’ve been hanging with,

therapist moms.”

“Only you can make the difference between life and death for your rabbit,”

the man read.boy’s arms swing as if palsied; he growls, anger-eyed,

whirls, retreats, crosses Hearst against traffic, screams and swirls.2

The book has good weight, solid feel, a fine gloss to its cover. A Maxon totem-pole-like abstract commands the right side, and columned text, complimentary colored – ochre, orange, rust – southwestern feel – the left. You sense in its construction deep care/attentiveness. The text is modest (30,000 words, I’d estimate) but complete and enriched by illustrations, black-and-white and color, more than two dozen full-pagers, as well as samples of Maxon’s and his older brother Robert’s correspondence, hand-printed in their distinctive styles – art in itself. The contents are nicely spaced, beautifully laid out. Kudos to editor Gary Groth, designer Sean David Williams, production guy Paul Baresh. Oscars for all. Every author should be so well-served.3

The book has good weight, solid feel, a fine gloss to its cover. A Maxon totem-pole-like abstract commands the right side, and columned text, complimentary colored – ochre, orange, rust – southwestern feel – the left. You sense in its construction deep care/attentiveness. The text is modest (30,000 words, I’d estimate) but complete and enriched by illustrations, black-and-white and color, more than two dozen full-pagers, as well as samples of Maxon’s and his older brother Robert’s correspondence, hand-printed in their distinctive styles – art in itself. The contents are nicely spaced, beautifully laid out. Kudos to editor Gary Groth, designer Sean David Williams, production guy Paul Baresh. Oscars for all. Every author should be so well-served.3

The foreword, by Robert, informs that Maxon had been viciously “mocked” as a child but grew into “an inordinately advanced individual” and “a great artist.” Whyte’s preface notes that Terry Zwigoff’s documentary Crumb (1994), which brought Maxon to national attention as “an unkempt weirdo who lived... on skid row” who engaged in devotional practices which included sitting on a bed of nails and performing a cleansing ritual of passing a three-inch-wide, fifteen-foot-long cloth through his digestive tract, concealed that he was “a vastly complex, gentle and wise man” with a deep knowledge that encompassed everything from arcane religions to the how-to’s of street survival, and an “irrepressible creativity.”

ii.

drop of hours old rain falls from glass-paneled awning;

filigree across hood of meter-anchored green datsun“yeah, well, I should go to class. I, like, failed gym.” she

said.

u.s. grounds jets days after crash, 157 dead.

KIZZ MY BLACK ASS. SHORTY THE PIMP. EAZY MUTHA F

buddy guy’s mother told him, "you don’t want to be here, you better not

come here."man in flowered skirt, full-length, mismatched earrings,

beard for Fat Tuesday – or forever – smiles over keyboard.

Even those familiar with Maxon’s story will find much in Whyte’s telling to drop their jaws even further toward the floor. Those who read the book fresh-eyed probably haven’t stopped shaking their heads yet. All the bases are covered. The brutal ex-Marine father. The speed-addicted mother. The ego-shattering ridicule from Charles and Robert.4 The seizures since age 11. The failed relationships and bad LSD trips. The molesting of women in public, leading to criminal prosecution, a guilty plea, and psychiatric hospitalization.

In consort with these assaults – and extending beyond the last of them – are Maxon’s quests toward sandhu-hood. Sleeping on the floor of a barely furnished welfare hotel. Solitary treks, penniless, often on the point of starvation, for hundreds of miles. Fasts of up to sixteen days (“A fantastic spiritual experience.”). Ten- to twelve-hour stints of meditation. A body-damaging vegetarian diet. Sitting lotus-positioned with begging bowl on San Francisco’s Market Street. Discovery of a previous life as a 19th century Norwegian silversmith (“Fjord”).

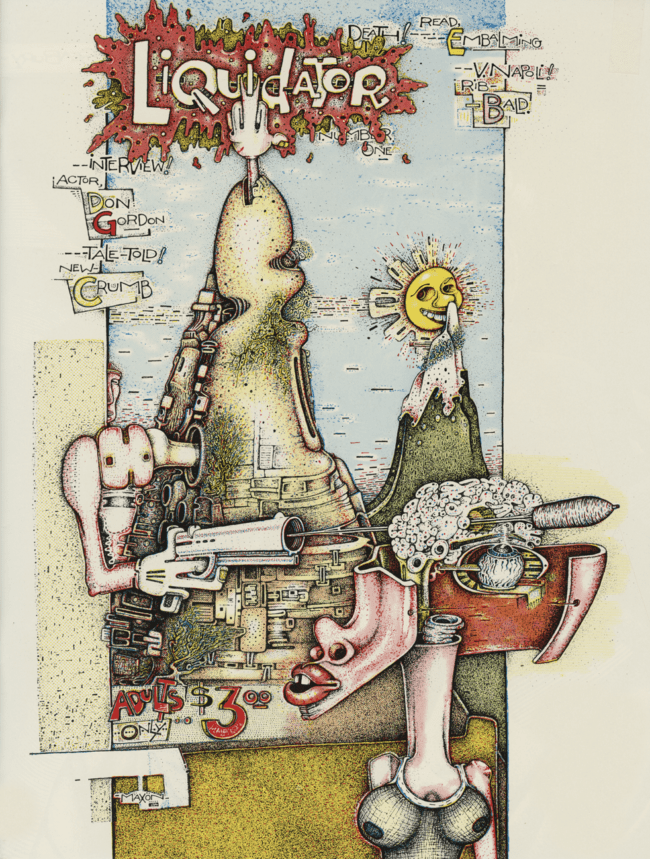

Out of this, Maxon built a persona as an “artist” and a career in “art,” both assembled in bits and pieces, as if a sculpture from cast-off objects. Drawings published by Robert in his magazine Weirdo led to invitations to contribute elsewhere. Requests to illustrate books and album covers followed. Collectors cast their eye on – and opened their wallets to – him. Supporters sponsored outlets for his work. Eventually he left street life – and public assistance. Eventually he entered a mutually sustaining relationship with Yannick Inguey, a Laotian-born French woman whose uniqueness in background and presence seemed to suit his own.

Whyte relates this story in an open, engaging style, unburdened by jargon or portentous analysis. He does not call for assistance from “experts,” whether of “High” or “Low” art, whether from those attuned to artists already ensconced within museums and galleries or to those laboring in flop houses and back wards. He conducted over thirty interviews with Maxon5 and had access to his correspondence and unpublished manuscripts. He contacted Robert and friends of Maxon. He even interviewed two of Maxon’s former girlfriends, who revealed an unexpected and sympathetic view of him. (Ingey seems not to have spoken to Whyte, and I suspect posterity will have to do without her memoir of their time together.)

Whyte comes across as someone who has seen enough art to be confident in his own judgments. He considers Maxon’s writings to be “complex” and “intriguing,” “alien” yet “erotic.” He finds his visuals “extraordinary,” “perceptive... and original,” “provocative and profound,” rich with “foreboding,” demonstrating “arrestive inventiveness” and mastery of “composition, detail and technique.” Most impressively to me – since it underscores my own shortcomings – is his ability to get beyond Maxon’s externals and, while avoiding none of them, relegate them to a place where they do not interfere with his gaze. He views Maxon’s deviations from the norm no differently than most of us would another’s choice of eyeglass frames.

iii.

silence, paper shuffles, “Mocha!” called beneath baroque violins, one

laugh from the corner. four mathematicians arrive on pre-work meet.49 new zealand dead; 11 tunisian babies

man on sofa reads mcclanahan’s tale of

two-nosed, witch raised-murderer turned mall developer.the poet becalmed in the corner seeks

the mud he played in when four, removed from time.

I have no argument with any of Whyte’s critical judgments. If I have a problem, it is in another area – and one which may lie entirely within me. I have this unfortunate predisposition toward judging the success of people’s lives, not in a “Who-has-the-most-toys?” sort-of-way but in one which is more ineffable. I am not sure that such a judgment can be made, yet it hovers over me like Joe Btflpsk’s cloud. Things would be sunnier without it. I also think that for anyone who had survived as long as Maxon, that verdict has been rendered in the only way that matters. Still the question drizzles on me, so...

Whyte seems to judge Maxon’s life a success. His thesis seems to be that Maxon suffered tremendous psychiatric damage in childhood6, which set him on a “tortured journey” in which, through art, he emerged victorious having achieved “a life of freedom, spontaneity and creativity.” (This mirrors Maxon’s own view, which is that his quest had been for “individuality” and “freedom.”

“‘Individuality,’” for sure,” I say over my espresso in the cafe. “‘Creativity,’ yes. ‘Freedom’ and ‘spontaneity,’ I am not so sure.”

Adele looked at me.

“These rituals,” I explained, “the meditating and diet, seem pretty iron-binding.”

“You probably carry a different definition of ‘freedom,’” said Adele. “If it brings Maxon that feeling, who’s to say he’s not having it and lucky to feel that way.”

While I was working on these thoughts, Frank Bruni opined in the Sunday Times about the implications of the recent college admissions scandal in which wealthy parents bribed and defrauded their children’s way into desired colleges. The principles thereby instilled in these children, Bruni wrote are:

That nothing in your life is too sacred to be used for gain. That you do what it takes and spend what you must to get what you want. That packaging matters more than substance. That assessments made by outsiders trump any inner voice.

Whatever else you might say about Maxon, I thought, you have to admit he stands at the opposite end of that value scale.

I sipped my double espresso. He had told Whyte that, while money and recognition were nice, it was the “struggle” that was “rewarding.” I had to agree. Gratification came from the work. If it was good, it triggered the right chemicals in the brain. The puzzle was how to sustain the buzz beyond its initial burst. My cup was almost emptied. Where our feet start from and how they end up seems determined by so much within and without – the particles of luck and intent and beyond-anyone’s-control-or-foresight – flying about as if within a cyclotron – making comedy of plans and judgments but not ruling out the efficacy of either. You take your time; you suck up information; you place your bets so each leg goes on forever.

- It is part of Maxon’s burden that Robert Crumb’s prominence as a cartoonist has so commanded the family surname that his siblings are commonly referred to in the literature by those given them at birth. Whyte takes this approach, as will I.

- The author wishes to acknowledge the continued influence of Stephen Ratcliffe’s “Day Poems.”

- Before we go further, in the interest of full disclosure, let me say that my article is end-noted twice as a source for the book, and in the body of the text, my “incisive observations” and overall sagacity are saluted.

- There were five siblings. The eldest, Carol, has kept out of the public eye and seems to have led a conventional life. Charles never lived outside the family home and committed suicide at 50. Sandra, the youngest, became a radical feminist, demanding reparations from Robert for his misogynist comics, and died at 52. Robert is now 76 and Maxon 75.

- The first of these, according to Whyte’s endnotes, occurred in 2003. This was followed by a fallow period (one interview each in 2004 and 2010) and then a flurry, with some talks lasting more than two hours, until they ended abruptly in March 2013.

- Everyone who writes about the Crumbs accepts the facts as repeated by Robert and Maxon about the toxicity of their upbringing. Certainly the death of two of the children by mid-adulthood seems confirmative, but when I think about it, it seems that multitudes of children have experienced more brutality and greater deprivations than that related by the brothers and yet were able to better adjust to society than Charles or Robert or Maxon or Sandra.

On the other hand, when I started to discuss this with my wife, she said that when I got to “brutality” and “deprivations,” she thought I “would end up with how surprising it was for two of these children to end up becoming significant artists.”