BATMAN: YEAR ONE

GROTH: So you started working for Bob Kane in ’39?

ROBINSON: Right.

GROTH: And you were simultaneously studying journalism at Columbia?

ROBINSON: Right.

GROTH: Did Bob Kane have his studio in the Bronx?

ROBINSON: Yes. He had a studio in his family’s apartment on the Grand Concourse. His bedroom was his studio. I got the room blocks away from Bob. I rented a room from a family.

GROTH: So you were in the Bronx.

ROBINSON: Yeah, as was Bill Finger.

GROTH: What did you start doing for him?

ROBINSON: Well, I first started lettering right away, and inking backgrounds. In a very short time, I started inking the other figures and learned to draw Batman. And I guess over the first year, I began to ink the whole thing.

GROTH: And it was all learning on the job?

ROBINSON: Oh, yeah, and around the clock. We all worked very hard on this thing — I guess maybe [they did] more than me, because I was also going to Columbia classes.

GROTH: And this was in Bob’s home?

ROBINSON: No, I would work in my room. We’d meet almost every day, and with Bill very often. We would go out to dinner or lunch and we’d talk comics incessantly, ideas for the strip and characters. I felt that I was part of a team. Unfortunately Bob did not feel that way, most of all with Bill. He should have credited Bill as co-creator, because I know; I was there. The Joker was my creation, and Bill wrote the first Joker story from my concept. Bill created all of the other characters — Penguin, Riddler, Catwoman. He was very innovative. The slogans — the Dynamic Duo and Gotham City — it was all Bill Finger.

GROTH: At what issue did you come in? The first issue had been printed by the time you signed on.

ROBINSON: That was printed and I guess the next one must have been already in the works for some weeks.

GROTH: So, very early ... third or fourth issue.

ROBINSON: Yeah, it was very early. The issues at the end of ’39.

GROTH: Did Kane and Bill Finger work in Kane’s home together?

ROBINSON: No, Bill would work in his own place. We’d get together for conferences and meetings and exchange ideas.

GROTH: What exactly did Bill Finger do? Did he write the strip?

ROBINSON: Oh, he wrote it, all of the stories.

GROTH: From the very beginning?

ROBINSON: From the beginning, as soon as Bob got the mission really, or the suggestion, to come up with a character to compete with Superman — it was the same publisher. He contacted Bill right away. They co-created the feature and Bill wrote it. Bill also contributed to the visual concepts and Batman’s persona; also the origin stories of Batman and Robin.

GROTH: So why is it credited exclusively to Bob Kane?

ROBINSON: Well, Bob went down alone and sold it to DC. He had been doing comics for them already. Nobody knew that Batman was going to be a success right away. The first time I saw Bob, he was still doing these supplementary strips. He had been doing mostly humor. He wasn’t an adventure artist. The only adventure strip he did was called Clip Carson, which I also worked on. Another one was Rusty and His Pals. When I started Batman, I was also doing those — Clip Carson and Rusty. After several issues they were dropped, because Batman became the focus.

EARLY DAYS AT DC

GROTH: So essentially, Kane had a mini shop, consisting of you and Bill Finger and himself. He got the assignment from DC and he paid you and Bill Finger, is that correct?

ROBINSON: Right.

GROTH: DC paid him, and he split it up as he saw fit.

ROBINSON: In effect, right.

GROTH: How were you paid, by the week or by the job?

ROBINSON: In the beginning it was by the page, as were most people.

GROTH: So if you ink one page, that would be one rate.

ROBINSON: Well, it was by the story. I don’t want to get into the sordid details, particularly because I was making more selling ice cream, as it turned out! We were going to leave.

GROTH: You and Bill?

ROBINSON: Yeah. We began to get offers all over the place once Batman became successful. They couldn’t get Bob, so they went after his staff.

GROTH: Other publishers?

ROBINSON: Yeah. Once we got other offers and wanted to leave, DC stepped in and made us an offer to work directly for DC. After the first year and a half maybe, we switched over and we no longer worked directly for Bob. In fact, I rarely saw him after that.

GROTH: It happened that quickly, about a year, year and a half after you started working for him?

ROBINSON: Yeah, off the top of my head it was about that time. I remember we took an office in the Times Building in Times Square. Bob rented it for George Roussos and I to work in. That was before DC hired us. We hired George to be my assistant, to ink the backgrounds, which left me more time to do all of the figures and some of the pencils. The office overlooked Times Square. When you see those famous New Year’s photos...

GROTH: Of course.

ROBINSON: It was right there.

GROTH: What year would that have been when you had your studio there?

ROBINSON: Probably mid-’40, beginning of ’41. I’d say by mid-’41 we were working at DC.

GROTH: But you were still working on Batman, and DC was paying you directly?

ROBINSON: That’s right, when we closed that studio and began to work for DC at 480 Lexington Avenue. So those were the few years that I actually worked at DC, which was a very interesting time. Working there at first were Siegel and Shuster, before the breakup. Jerry would come in at times and do his writing. And Joe Shuster was doing the drawing, and he worked at the next drawing board.

The next desk on the other side was Jack Kirby. The next desk was Fred Ray, who did the great Superman covers, and also Congo Bill. Mort Meskin, who was one of my best friends, who I brought up from MLJ.

GROTH: So DC actually had a bullpen set up of artists.

ROBINSON: Oh, yeah. Yes, they had a big bullpen.

GROTH: Were you on staff or were you paid as a freelancer?

ROBINSON: No, I was then on staff. They made me an offer of a salary and extra things that I would do.

GROTH: And all of your fellow artists were also on staff?

ROBINSON: Well, they might have varied. Some of them might have been working freelance.

GROTH: Did you get health benefits?

ROBINSON: No, I think I got a life-insurance policy from them. No, there was no such thing as health care in those days.

GROTH: Let me get back to when you worked for Bob near his place for a year or so. What was the atmosphere like and what was Bob Kane like, and how did you work together?

ROBINSON: Well, I liked Bob. He was very personable. I must say that he had a pretty big ego. Bill [Finger], on the other hand, did not. He was very quiet, intense, unassuming and insecure. His position vis-à-vis Bob made him more insecure, because while he slaved working on Batman, he wasn’t sharing in any of the glory or the money that Bob began to make, which is why we were going to leave.

GROTH: Did he recognize that that might have been unfair at the time?

ROBINSON: Well, of course you can’t ask Bob any more, but that should have been addressed to Bob. We thought it was unfair, of course. That was one thing I would never forgive Bob for, was not to take care of Bill or recognize his vital role in the creation of Batman. As with Siegel and Shuster, it should have been the same, the same co-creator credit in the strip, writer and artist. And Bill died broke. Imagine creating Batman and all of the money that it’s made ...

He had a wife and a kid, and he had a very tough time. He was not even appreciated, I think, by DC editors at the time.

GROTH: Was he fully aware of the unfairness of the situation?

ROBINSON: Of course: He was never recognized by Bob until after his death, unfortunately. He helped shape the character of Batman and even the costume and everything else. You could tell what went on before; it was that recent.

GROTH: Why do you think he wasn’t more aggressive in standing up for his rights?

ROBINSON: He was not an aggressive guy.

GROTH: Temperamentally?

ROBINSON: Yes — and insecure. If he had gotten that credit, it would have built up his self-esteem.

GROTH: And Bob was very secure?

ROBINSON: Bob was ultra-secure, at least on the surface. I don’t believe that in reality he was so secure — if he were, he would have been able to acknowledge Bill’s contributions, as well as my own. So that made it difficult.

We began, as I said, to get these offers. I got an offer from Busy Arnold, who was one of the big publishers who began to make offers to Bill and myself. He offered to make me editor-in-chief of his line of books. I could draw whatever characters I wanted. I wondered if I could have done it, in retrospect. I really sweated over that decision. But I was still imbued with Batman. I was there from the beginning. The editor at the time, Whit Ellsworth, who I liked and got along very well with, entreated Bill and me to stay with Batman and I could do my own stories. I didn’t have to work with Bob.

GROTH: You could do your own Batman stories?

ROBINSON: Yeah. I still finished Bob’s drawings for a long time, but I ended up doing my own Batman covers and complete stories on my own. The stories I did, I would do complete — pencils, inks, backgrounds and, at times, even the color.

THE TRAGEDY OF BILL FINGER

ROBINSON: I long thought that Bill ... Well, as you know, he got a really raw deal; he was unappreciated in his time. He died broke, never got credit as co-creator of Batman.

GROTH: That’s very much what Alvin Schwartz said, possibly even more forcefully. In fact, he actually ascribes much more authorship to Finger than he does to Kane.

ROBINSON: Well, as far as writing, absolutely. Bob never wrote anything. Bill wrote it all, and he helped mold and create the character itself and almost all of the other characters. So there’s no question. It should have been as much, if not more, of a collaboration than Siegel and Shuster.

GROTH: In an essay about Finger, Schwartz wrote,

Unfortunately, Bob was unable to give Bill the credit he deserved, not only because of his own shaky sense of personal and professional worth, but because of the legal tie-up his shrewd and protective father arranged at a time when DC was in delicate negotiations with McClure Syndicate they could not afford to have anyone rocking the boat. This legal tie-up gave Bob unique rights to Batman even though it was Bill who supplied the heart and soul of the idea that somehow also managed to turn Bob’s amateurish and distorted drawing into an advantage.

Can you comment on that? How far away is that from your take on things?

ROBINSON: I think it was simpler than that. At that time, neither Bill nor I ever met with DC, with the editors. Bob was given the assignment to come up with a character to compete with Superman by Vin Sullivan — who was the art director, and then afterward Whitney Ellsworth, but I think Vin Sullivan was there at the time. Bob immediately went back and called Bill to help him create the character, and flesh out the concept and write the story. Bob took it down to DC and signed up and presented himself as the sole creator. Nobody knew anything about Bill or myself until later on. It was already signed, they’d dealt with him, and they didn’t want to have to deal with someone else unless necessary. We were working directly with Bob, actually, the first year, year and a half. Then Bill and I began to get offers from other publishers. Everybody wanted to have somebody who was associated with the success of Batman. DC finally learned about our existence and that we were going elsewhere, they immediately called us down and signed us up and we worked, after that, directly for DC and not for Bob.

GROTH: Would it have been considered a kind of breach of professional etiquette to have gone around Kane and gone straight to DC at some point and said, Look, we co-created Batman and we’d like to have a share of the rights to the character?

ROBINSON: Well, we never presented ourselves: at least I didn’t, as the co-creators. Bill had legitimate cause for saying that, but I don’t think he ever did, either. We were naïve. No, we were leaving and they heard that the Batman team was disintegrating. So they called us both in. As I said, Busy Arnold offered me the editorship of all of his magazines, and I could do any lead feature I wanted to, so I was really torn about whether to go or not. I still had some personal attachment, I believe, to the character of Batman. I had created the Joker and helped mold Robin, named him. Bill, who was there from the beginning with the co-creation, wanted to leave. We were finally persuaded to stay — with a lot more money, of course — and we stayed with DC. That’s how that came about.

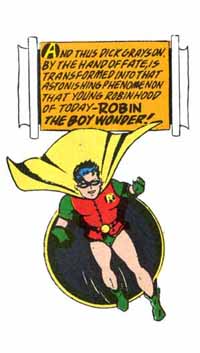

GROTH: I assume you’ve read Gerry Jones’ new history of comics, Men of Tomorrow. There’s a little contradiction I wanted you to clarify between what you’ve said previously about who created Robin and how Jones related it. Jones wrote, “When Bill Finger felt Batman could use a sidekick to talk to, he and Robinson created Robin, the Boy Wonder.” Now, you contradict that in an interview that you did with Comics Interview when the interviewer asks you, “What about Robin? You were responsible for his creation” and you reply, “No, no. I was not. I can’t take credit for that. As I reconstructed it and Bill confirmed my recollection, Bob and Bill had the idea of having a kid and discussed that idea before I arrived.”

ROBINSON: Right. That’s basically true. Gerry [Jones] I think was very accurate in his interviews. He interviewed me extensively for the book. I think he did a very fine job. In any event, yeah, more accurately, adding a kid was under discussion. I’m sure it was Bill’s idea for adding a boy. That I would attribute to Bill without question. When I came in they were already discussing possible names. So I joined the discussion of the creation. There was nothing on paper yet, nothing but the idea of adding a sidekick. And I know that was Bill’s idea to add a sidekick, from the discussion that ensued. The impetus came from Bill’s wanting to extend the parameters of the story potential and of the drama. He saw that adding a sidekick would enhance the drama. Also, it enlarged the readership identification. The younger kids could then identify with Robin, which they couldn’t with Batman, and the older ones with Batman. It extended the appeal on a lot of levels.

GROTH: And you’re sure it didn’t come from Bob Kane?

ROBINSON: No. He fleshed it out, as we all did in discussion, but the idea of adding that character was Bill’s.

We had a long list of about 30 names, and we kept adding others. The names are very important for the characters. Bill was very specific about that, as well as Bob. Most of the names, as I recall, were of mythological origin — Mercury and others. None of them sounded right to me, or to anybody, because we never agreed on any one.

My reservation was that I thought that it should be a name that evoked an image of a real kid. He didn’t have superpowers, nor did Batman. That was what distinguished it from Superman and the other superheroes. I thought the boy should be the same. And thinking of a more human name, I came up with Robin because the adventures of Robin Hood were boyhood favorites of mine. I had been given a Robin Hood book illustrated by N. C. Wyeth — I think it was a 10th or 12th birthday present. It was a big, very handsome book for the time, very elaborate because it had full-color illustrations, maybe a dozen throughout the book. It was the full text with full-plate tip-ins. I remembered those because I had pored over them so many times as a kid. I had a vision of Robin Hood just as Wyeth drew him in his costume, and that’s what I quickly sketched out when I suggested [the name] Robin, which they seemed to like, and then showed them the costume. And if you look at it, it’s Wyeth’s costume, from my memory, because I didn’t have the book to look at. But it is pretty accurate: the fake mail pants, the red vest, upon which I added the little “R” to correspond with Batman’s bat on his chest. When I started to letter the strip, every legend I did started off with a little round drop-out white letter. So I thought of that for the vest.

GROTH: Would you have seen the Douglas Fairbanks Robin Hood?

ROBINSON: If I did, I don’t recall it.

GROTH: You probably saw the Errol Flynn version, then.

ROBINSON: Errol Flynn I remember, but my visual came from the Wyeth illustration — of that, I’m positive. I have it in my library. It was such a special book to me. I carried it wherever I moved.

GROTH: Schwartz has a theory about why Bill Finger was not more aggressive about pursuing his own rights. One thing he said was that Bill was a procrastinator and always late on his deadlines. Is that true?

ROBINSON: Yes, quite often he was. It wasn’t because of procrastination. It may have been a part. We all procrastinate sometimes, I suppose. His problem meeting deadlines ... Bill was a craftsman. He couldn’t let anything go unless it met his sense of perfection. He really worked on his scripts, and he wasn’t a fluent writer. Some writers write very easily and produce a lot. Others, some of our greatest writers, sweat out every word. Bill was in the latter category. He really worked on his scripts and it didn’t come easily. He tried to do a creative job each time. They didn’t appreciate it. So if he didn’t keep up with the hectic deadline pace, it was understandable. To them, it was the bottom line. If you met the deadline, that was most important. Too often he didn’t.

GROTH: Schwartz has a more psychological explanation, and I’d like to get your take on it. He said Finger’s relationship with his parents was very tumultuous. He wrote, “I always suspected, once I came to know Bill well, that somehow, symbolically, he had contrived this method of imaginatively getting rid of his own parents, in the origin of Batman, whose exploitation of Bill had been noticed and talked about at the DC offices well before my arrival a few years later. It was probably Jack Schiff who told me how Bill’s parents would be waiting to grab Bill’s check as soon as he received it at the office.” And then he went on to write, “Bill’s inability to meet deadlines consistently was clearly due to an angry withholding, a tendency to delay and doodle with a story idea long past its due date. In a deeper sense, his unexpressed anger made it difficult for him to focus on a single task. Once he had a story idea complete, the mere chore of typing it became too boring.” Think there’s any truth to that?

ROBINSON: Who knows what the real truth is psychologically? That’s speculation. I think all of us can read psychological reasons and motives into anybody’s actions. I wouldn’t have come to those conclusions, and I knew him quite well. I knew him before Schwartz and Schiff, and afterward. That might have been Schwartz’s observations, but it wasn’t mine — nor did I ever hear anything like that from Bill or anyone else at the time.

One last word about Bill: He was a very sweet and gentle guy. Bob never admitted to his contributions, and he was really shoved in the background and this didn’t add to his self-esteem. His lack of confidence in himself grew, even though it was not reflected in his work, which remained top-notch. But he had no confidence, and the editors and everybody at DC and Bob took advantage of that. It was pitiful to see. I remember many times my back crawling when the editors at DC berated Bill for being late on a script, even if it was wonderful, if it was a day late. It was embarrassing and degrading for Bill.

GROTH: Did the editors at DC treat everybody like that, or did they particularly victimize Finger?

ROBINSON: I think they treated others that way, but they particularly victimized Bill. I think he became kind of a scapegoat for things. I’m not one to psychoanalyze others, but it seemed to me there was some resentment, maybe his ability, his freedom. You know, they were frustrated editors and writers themselves, from Mort Weisinger to Jack Schiff; I think they enjoyed exercising their power. This is just my inner feeling about it.

GROTH: You know, it’s odd that he would be as passive as he was or as insecure as he was and be as widely read and intelligent.

ROBINSON: Yeah, but he got no feedback. I recall one interview with Bob where he even denied that Bill wrote any of the scripts — and he wrote them all. I think if he was nurtured a little more, recognized, that would have bolstered his esteem. You can just take so much that you begin to not believe in yourself.

GROTH: My impression of the comics industry, especially then, was that people took advantage of whomever they could take advantage of.

ROBINSON: Well, that’s true in many instances. We were all pretty naïve then. We didn’t know too much. But Bill was always, as you know, a very versatile writer. He went on to write for TV and a lot of other properties in comics, as well. I know when I first took an apartment on the Upper West Side, I shared it with another writer who was writing in television, and they collaborated on a lot of early TV scripts. So he’d be working at my place quite a bit. This was even after we separated. This was years after Batman.

GROTH: What years would those have been, approximately?

ROBINSON: Probably ’50s and maybe into the early ’60s.

GROTH: Didn’t he die young, relatively? And you were good friends until his death?

ROBINSON: Yeah, and I knew his wife, Portia, very well, too: very intelligent, very lovely woman. They were very much in love in the early days. I was with him when he was courting her. She came from — I think it was Albany or Rochester. I remember many times we’d be out for lunch or dinner and he’d say, “I have to call Portia,” and he’d duck into a phone booth. We couldn’t pry him out. He was talking in a phone booth for a half an hour on our way to dinner. Later she moved to New York and I would visit them at their Village apartment, and we would often go out to dinner.

GROTH: Did he gain in his sense of security over the years?

ROBINSON: I think possibly some. He did write for a multitude of places, but he was never able to dig himself out of a hole financially. He never could turn out enough at the level he was writing.

(Continued)