Throughout his storied career in manga, Kazuo Umezz told horror stories for children - stories in which ghastly horrors visited youth in familiar settings. Violence in the home is a recurrent theme, as is violence at school. Many of his horror stories involve the behavior of adults suddenly changing: a parent becomes mysteriously aggressive after an inciting trauma; a teacher or a nurse turns cold-blooded; a child discovers a horrible secret about their family; or perhaps an enraged stranger emerges unexpectedly to dissolve the normalcy of the house. Sometimes the child also suddenly turns toward evil, but adults in authority are always implicated by their own cruel misdeeds. All of these stories revolve around a terror that the family could turn violent or be revealed as violent, as any child in a capitalist society knows. Comfort and safety could vanish from your home. Your mother or father could suddenly change. Love could leave their hearts, never to return, and nobody would know except you, the powerless child under the care of monsters.

I do not believe that Umezz hates the nuclear family. At the very least, I do not believe this to be the primary, intentional message of his work. Consider The Drifting Classroom (1972-74), wherein the inciting incident of the story, prior to the supernatural rupture that sends the titular classroom drifting through time and space, is young Sho’s argument with his mother. Sho’s mom is unfair to the boy - she yells, she is too harsh. Yet Sho’s narration reminds us repeatedly of his remorse for the ingratitude he showed his mother on that day, the anger and failure to love that marked the final moments of what he did not know would be the last time he saw her. In time, Sho’s mother takes on the role of a guardian angel, protecting Sho and his classmates, who are trapped in the future, with a pious, religiously ecstatic drive to follow the child's psychic cries for help in the present. In the series’ arguable climactic turn, an effigy of Sho’s mother is created under the boy’s command, the icon of a new national religion for the stranded school. Where once Sho experienced rage at real conflicts with his mother, his spirit has been given strength by the idea of the mother. The concept of his mother’s maternal compassion, her fortitude as nurturer and protectress, builds Sho into a great leader, freed from the frustrating hassles and conflict of dealing with the real woman.

This is Umezz’s interest: teasing out, for entertainment purposes, the dissonance between the idealized family and the actual resentments a child feels within their family. Mother is an ideal of nationhood, the soil from which you grew. Mother is also the woman who scolded you, humiliated you, controlled your existence from home while your father worked long hours. How can both stories be true? Umezz’s horror prods at tensions implicit in justifying the nuclear family by depicting what for many, even among those who have lived it, is the unthinkable, the unspeakable: child abuse and cycles of familial violence. What if all of your anger at mom wasn't just in your head? What if it only scratched the surface of something scarier? What if you were the only one to live a nightmare? What if your mother hit you, and this time it wasn’t right?

Orochi (1969-70) is a horror manga which served approximately as a sister series to Umezz’s Cat Eyed Boy (1967-68, 1976). Both series marked a progression of Umezz’s short story horror works, as they are anthologies presented from the point of view of their eponymous supernatural protagonist/observers. The formula of a consistent narrator for self-contained stories casts Orochi and the Cat Eyed Boy in a role not unlike EC’s Crypt-Keeper or Charlton’s Mysterious Traveler; but unlike these omniscient, sarcastic commentators, Umezz’s observers inhabit their stories, wandering into the homes of those afflicted by supernatural distress to influence their lives and help them evade the threats lurking under their roofs. Cat Eyed Boy often has to hide from the people he follows; Orochi uses a supernatural ability to integrate herself into their memory. Cat Eyed Boy is a yōkai who takes the form of a little boy with unsettling feline features; Orochi is a spirit who has wandered Japan for untold ages in the form of a teenage girl. For the most part, Cat Eyed Boy does not directly influence the stories he is a part of (although later stories deviate from this premise), beyond battling creatures that find him in hiding or leaving traces of himself like overturned furniture or broken glass. Orochi, however, often spurs events into motion after taking pity on some distressed human. Whether dispersing gangsters, reanimating the dead, or simply asking the right question at the wrong time, Orochi prevents harm from coming to one doomed to a far greater calamity.

Family trauma and dark secrets held by parents choke the pages of Cat Eyed Boy and Orochi far more than the putrid forms of monsters and curses. In Cat Eyed Boy’s first story, the spirit of a deformed man haunts a young boy, who soon discovers his father to secretly be a murderer haunted by the same presence. Throughout Cat Eyed Boy, deformity, monsters and vengeful dead attack families from without, targeting children, while parents reveal themselves twisted by their own horrible secrets. Often, children learn that their father is not really their father - bastards return home for revenge, and demons reveal the cruelty which defines parents. Fatherhood in Cat Eyed Boy is defined by repulsion at what fathers once did, and the repugnant eruption of that unspeakable past into the lives of children.

Orochi presents more insular dramas, and the macabre is more explicitly born out of the family, albeit along matrilineal lines. The first volume presents two stories that serve as a program for the work’s themes. In the first ("Sisters"), a house of daughters, doomed to witness their beauty degrade, torment one another - only for the sister most deranged by her ugly fate to be revealed a bastard daughter deformed not by a heritable tragedy, but by her own misery and violence. In the next ("Bones"), a husband dies in an accident and Orochi resurrects him out of pity, but alive again he desires nothing more than to kill his wife, who fears him because she knows why he wants her dead. Women deplete and die by rage and hopelessness, mommy doesn’t love you, and adult men are both death and power incarnate. Parents become very suddenly afraid in ways a child could never understand - and for this, children suffer at their hands.

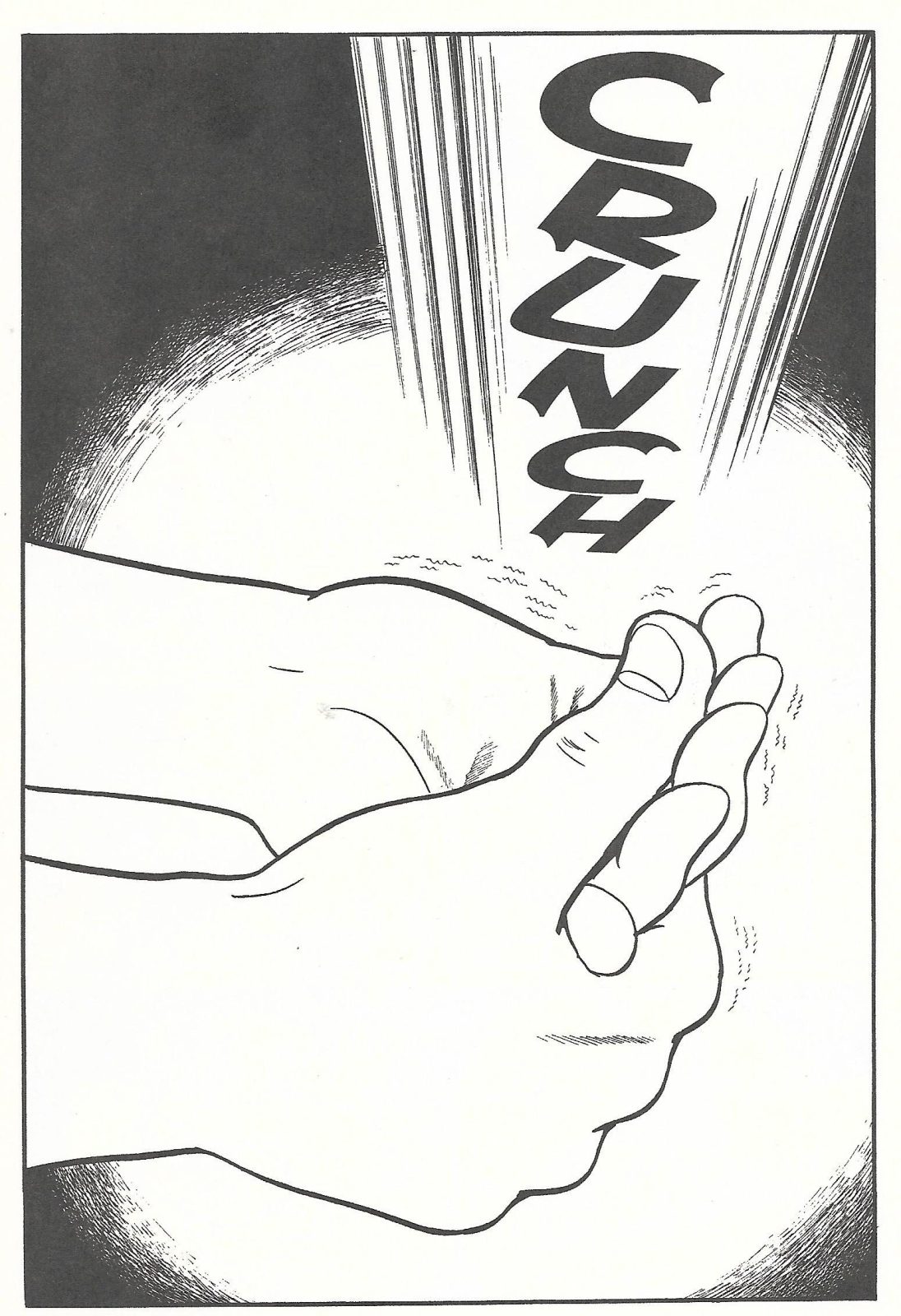

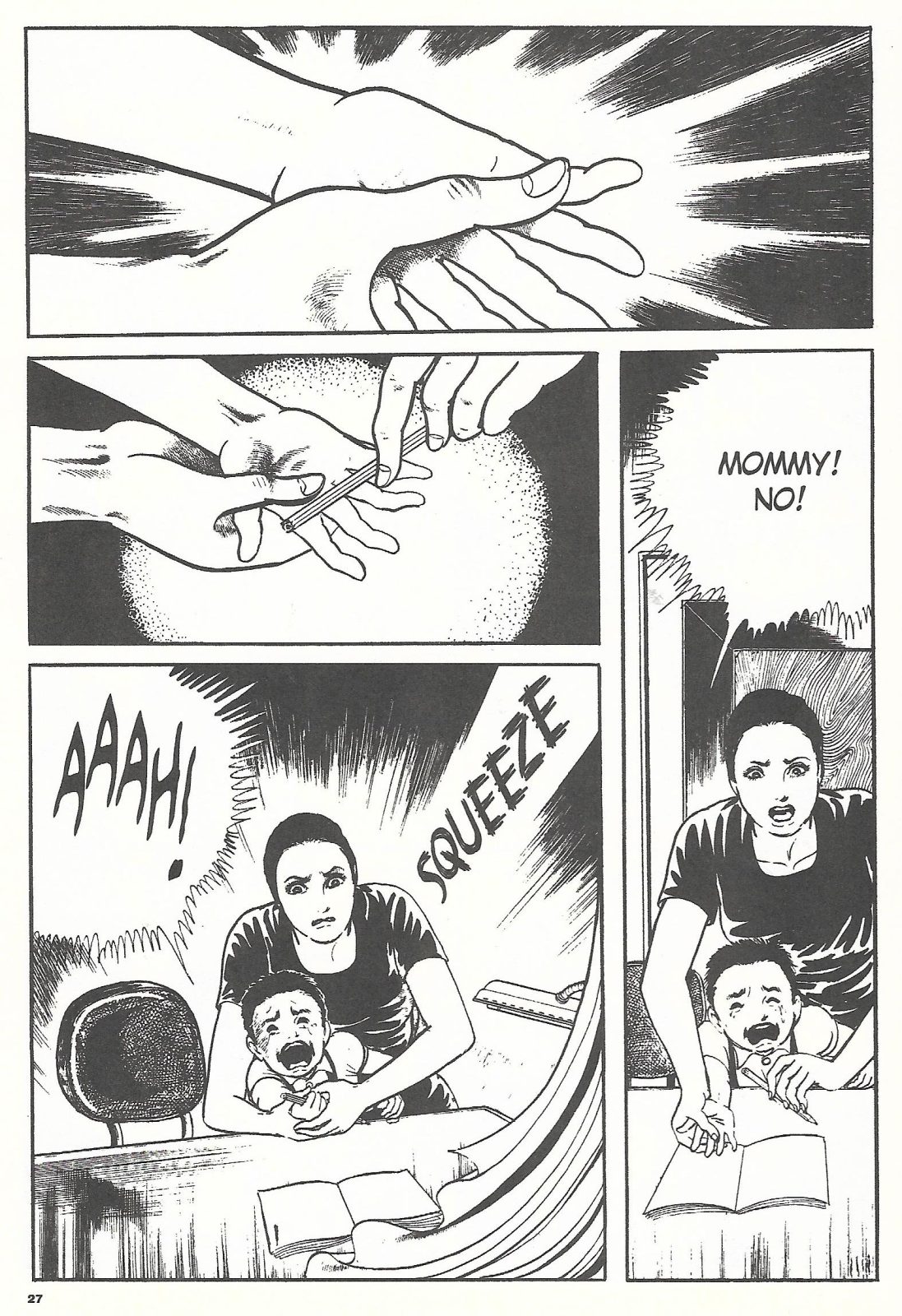

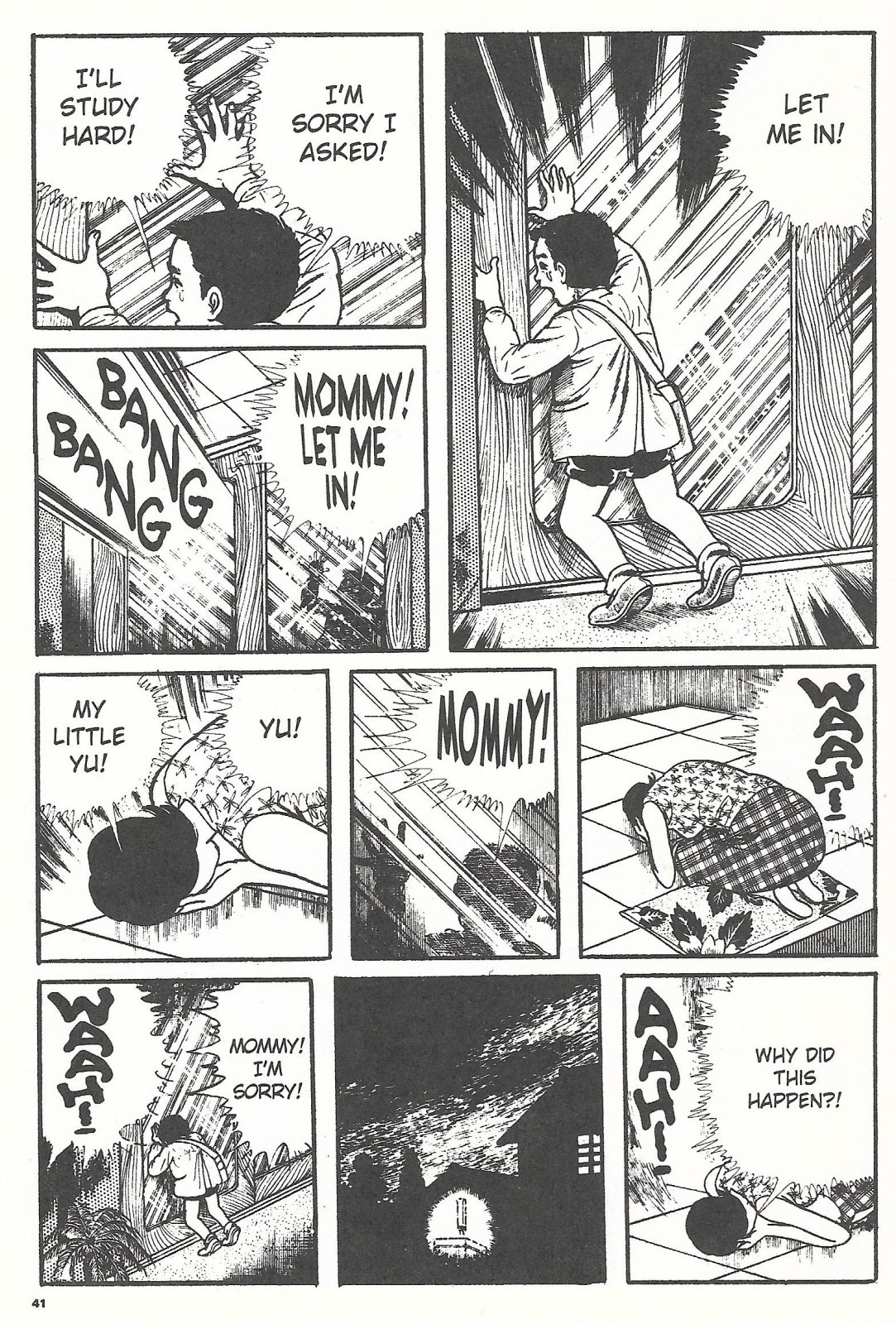

"Prodigy", the short story which opens the second volume of Orochi in the new VIZ edition (translated from Japanese by Jocylene Allen and adapted to English by Molly Tanzer), is a particularly intricate microcosm of the cycles of abuse that define the family in Umezz’s horror manga. It begins with a happy family wrecked by the trauma of an outside incursion. The Tachibanas are victims of a violent crime: a thief breaks into their home, and, caught in the act, slashes their newborn son Yu in the neck with a dagger out of desperation. The thief is apprehended and Yu survives, but Yu’s scar remains, a disturbing mark which drives his classmates away from him and leaves him an ostracized outcast. Indeed, the whole family was changed that night. Yu’s father, a brilliant graduate of a great university, descends into meekness, absence, and alcoholism. Yu was meant to be the brilliant son of his father, but just as his father became a shadow of a man, Yu’s grades slip into quiet mediocrity, and the greatness expected of his future fails to bloom. Yu’s mother, desperate, subjects Yu to cruel discipline and abuse, hitting the boy, screaming at the boy, working him through endless tutelage with the threat of his failure and the family’s ruin looming in his weary mind. Much of the story’s horror is simply the abjection of this household, with the certainty of a bright future snuffed out by chance and replaced with the violent rage of a desperate mother whose dreams were cut like her child’s fragile neck.

The scenario is that of a curse. But can a curse make a child fail arithmetic? Children disappoint parents all the time. Any child would know this. The horror, then, might be the horror of knowing why mommy doesn’t love you - or being able to learn why. Every tragedy in Yu’s life is structured around the scar on his neck: the absence of his father; his isolation from fellow children; the anger of his mother who blames the incident for the unremarkable boy he is becoming; and the lonesome, cloistered childhood he spends trying to appease her. Seeking answers, Yu finds the family of the man who broke into his home that fateful night - the thief was just a father, desperate to provide for his own family. Yu gets answers, and his mind turns to revenge.

The revenge Yu seeks, however, is an unexpected one for the reader - and Orochi, who has become Yu’s only friend as she observes the Tachibanas. Yu begins to study diligently, fanatically. He rises to the top of his class, sabotaging classmates who might outperform him. He stops sleeping most nights. Finally, the time comes for the boy, now a young man, to take his university placement exams. After the tests, he tells Orochi that he may not pass at all, then sleeps for three nights straight. The test results are stellar. His mother, panicked, attempts to have Yu’s results doctored, but Yu catches her, confronting and attacking her. Yu had become the son his mother always wanted, which she believed wasn’t possible - because she knew Yu was not her son. "Yu" was the son of the robber, stolen from his house in secret after baby Yu died from his neck wound. Yu’s mother inflicted her illicitly adopted son’s scar herself, to make the child seem to be hers. She never expected the boy would succeed. She was punishing the robber’s family by abusing their child.

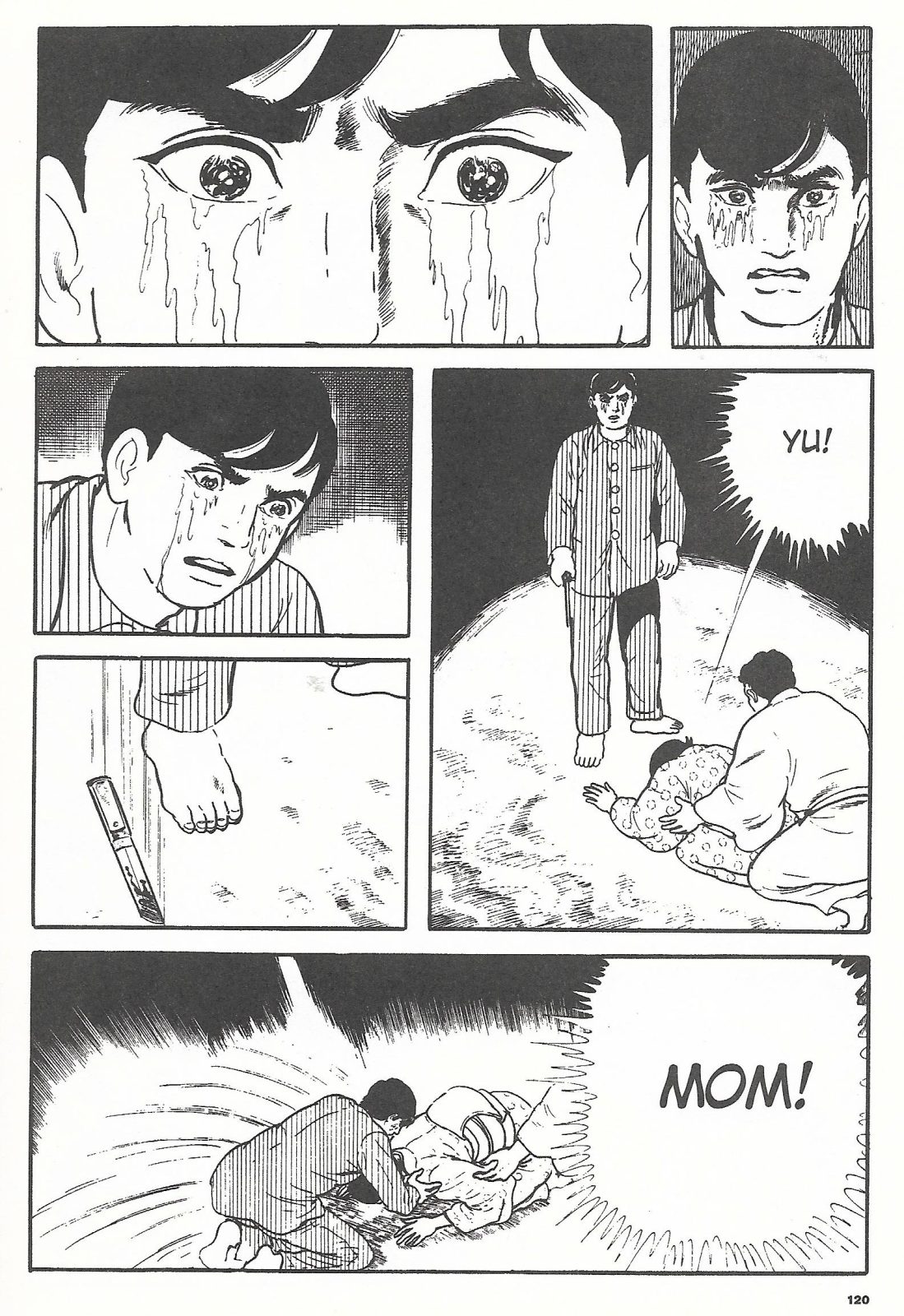

The soap operatic climax of "Prodigy" finds son, mother and father embracing, tears in their eyes. Orochi watches from the window, and observes: “Even if they hate each other, they’re still family. They really are parent and child.” This could be read as the triumph of nurture over nature - even if Yu was not born to the Tachibanas, he was raised as one. However, the turn to familial order and affectionate normalcy could not really have anything to do with Yu’s upbringing, which was built on abuse, neglect, and hurtful lies. In this moment, the Tachibanas are finally honest with each other. Yu was never their son, Yu’s mother hated him, and Yu’s father never cared about him beyond his horror at what his wife had become. There was never any love behind the aggression Yu’s mother subjected her child to, never any hope that he would improve. As Yu blossomed as a student, he was never driven to impress his family, because his ambitions were neither his own, nor were they really those of his family. All of them were driven by anger and sickening truths known but left unspoken.

And yet, Yu became successful. The family fulfilled its obligations as understood by society. Capitalist nations do not care if parents love their children - or why some children succeed, or even want to succeed. It just cares to reward a kind of success. There are many families like the Tachibanas, built on nothing and fueled by cycles of abuse. Not every family like this is successful, and perhaps not every family of winners is abusive, but the point is that it doesn’t matter; it can happen, so it does happen, and it happens often because the kind of people who succeed without cruelty do not anticipate what people sustained by cruelty are capable of. In the case of Umezz’s Tachibanas, their horrific curse-like existence is ironically fortunate, because it can be explained. Had a desperate, impoverished father not broken into their self-contained life and slaughtered their firstborn, had the boy who became Yu not been seized from that criminal family which died penniless and miserable, they would have no story for why they raised Yu under such inexcusable conditions. It could have happened anyway. There could have been no truth to reveal other than a father who burnt out, a mother whose anger could only be cast upon her most vulnerable and available target, and a boy crushed under the weight of a secretly broken home who couldn’t connect to others. But they were lucky. There was a secret. There was a truth to tell. A rationale to be freed from. The Tachibanas become a lucky family because they had an excuse for the normal horrors to which modernity can and does subject all children.

Before Orochi departs, she makes her only active appearance among the whole Tachibana family: stealthily, as they sleep soundly. She takes a bandage, placing it on “Yu’s neck... his mother’s wound... and his father’s tired brow...” She departs down the windswept road of the residential neighborhood, and tells the reader: “I’m sure their wounds will heal.” Many times before, Orochi’s magical remedies have failed - or rather, in their success, instigated the discovery of a social rot without cure. Without wounds, what ties does this family have to bind them in familial love? Will their hearts change as well? Can they love each other without damage that can be seen, a scar that tells a story? Yu’s scar was always a fiction, inflicted on him by his mother to tell a tale where he was her son. Orochi’s certainty that the wounds will heal might point to a future where this family will not be marked by pain. But without pain, what will become of the family?