Annie Murphy is here today with an interview with the preeminent creator of true crime comics, Rick Geary. Here's a bit of their discussion:

Sherlock Holmes is pretty big right now—as are detective stories in general. But Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who similarly laid out all of the information for the crime buffs, his glory was to wrap it all up in the end and tell you the answers. He let the reader feel smugness at their own correct conclusions, and shock at the surprises. Whereas, you leave your stories open-ended. What is it about this that appeals to you?

I guess it's just the way my sensibility goes. I like questions more than answers. And I like mysteries more than solutions. I'm a big reader of mystery fiction as well. And I find, in a lot of them the solution is kind of a disappointment. I like being carried along by the mystery of it. Because there's so much in life that's mysterious and I like the idea of laying out all the elements of a case, all the clues, and making that aspect of it as clear as possible. And still it's a mystery. I don't know, my mind just kind of falls in that direction. I don't know how else to explain it.

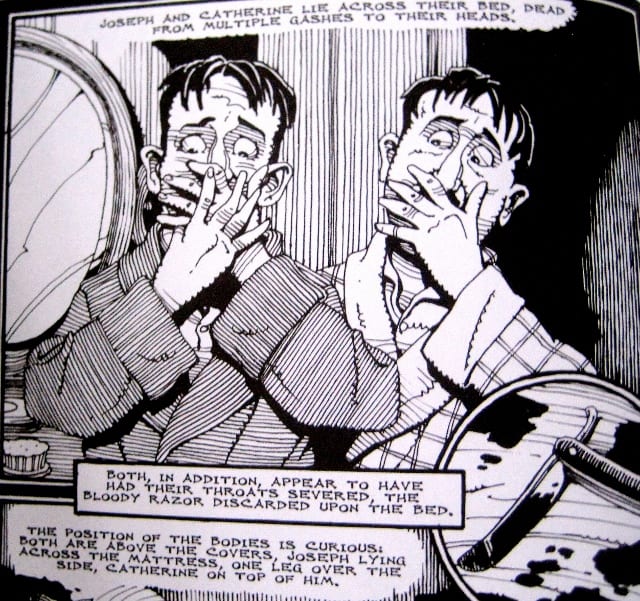

Well, I consider comics a subjective medium. If it's one creator, they are creating the story, characters, narrative arc, and all of the images. But I've noticed in your books that you do quite a good job maintaining an objective perspective. Is that something you value highly?Yeah, I try to maintain a kind of journalistic distance. But at the same time, it can't help but be subjective. Because I decide what details to include and what to leave out, what to emphasize. In fact, the very first two books that I did, the first two graphic novels in the series, the one on Jack the Ripper and the one on Lizzie Borden, they were told from within a fiction framework. I don't know if you read those, but--

I did, but it's been a while...

They're both kind of told by this fictional person. The Jack the Ripper book is in the form of a journal being kept by a fictional English gentleman. And then the Lizzie Borden one is from the point of view of this woman I made up who was supposedly a neighbor of the Bordens, a friend of the Bordens, who was telling the story. And after that one my publisher came to me and said: “This is kind of a problem. It makes the books fall into this crack between fiction and nonfiction, and they don't know how to classify them.” So from then on I adopted more of a journalistic outlook. Or as close as I could anyway; more of an objective viewpoint.

AND A QUICK NOTE FROM MICHAEL DEAN: If your name is Bob White and you took a photo of Robert Crumb and Gary Groth in the Journal's offices in California circa 1985, please contact The Comics Journal at dean "at" tcj.com. Thanks.

Meanwhile, elsewhere:

—Interviews. Annie Koyama is a guest on the Make It Then Tell Everybody podcast. Jaime Hernandez and Frederik Peeters are two of the most recent guests on Inkstuds. Pádraig Ó Méalóid talks to Kate Charlesworth, collaborator on the most recent book by Mary and Bryan Talbot. 13th Dimension interviews Jim Chadwick about the new digital editions of Jiro Kuwota's Batman manga.

—Reviews & Commentary. Robert Boyd has not one but two of his infrequent comics-related posts up, one on two recent books of comics history by Thierry Smolderen and Dan Mazur & Alexander Danner, and another on the comics issue of Artforum and the artist Erró's appropriation of Brian Bolland artwork. Tom Spurgeon reflects on Walt Before Skeezix and the new collection of early Bungle Family strips. (When I accused Dan this weekend of disliking every comics-related book published since the shutdown of PictureBox, he cited two books that he liked, one of which was The Bungle Family.) Tezuka biographer Helen McCarthy reviews Jonathan Clement's Anime: A History. Mark Fraenfelder recommends R. Crumb's The Weirdo Years.